Morus alba

| Morus alba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Moraceae |

| Tribe: | Moreae |

| Genus: | Morus |

| Species: | M. alba |

| Binomial name | |

| Morus alba L. | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Morus alba var. alba | |

| Synonyms[1][2] | |

|

Morus atropurpurea Roxb. | |

Morus alba, known as white mulberry, is a short-lived, fast-growing, small to medium sized mulberry tree, which grows to 10–20 m tall. The species is native to northern China, and is widely cultivated and naturalized elsewhere.[3][4] It is known as शहतूत in Hindi,Tuta in Sanskrit, Tuti in Marathi and Toot in Persian and in Armenian.

The white mulberry is widely cultivated to feed the silkworms employed in the commercial production of silk. It is also notable for the rapid release of its pollen, which is launched at over half the speed of sound.[5]

Description

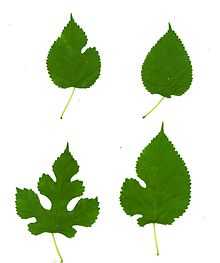

On young, vigorous shoots, the leaves may be up to 30 cm long, and deeply and intricately lobed, with the lobes rounded. On older trees, the leaves are generally 5–15 cm long, unlobed, cordate at the base and rounded to acuminate at the tip, and serrated on the margins. The trees are generally deciduous in temperate regions, but trees grown in tropical regions can be evergreen. The flowers are single-sex catkins; male catkins are 2–3.5 cm long, and female catkins 1–2 cm long. Male and female flowers are usually on separate trees although they may occur on the same tree.[6][7] The fruit is 1–2.5 cm long; in the species in the wild it is deep purple, but in many cultivated plants it varies from white to pink; it is sweet but bland, unlike the more intense flavor of the red mulberry and black mulberry. The seeds are widely dispersed by birds, which eat the fruit and excrete the seeds.[3][4][8]

The white mulberry is scientifically notable for the rapid plant movement involved in pollen release from its catkins. The stamens act as catapults, releasing stored elastic energy in just 25 µs. The resulting movement is approximately 350 miles per hour (560 km/h), over half the speed of sound, making it the fastest known movement in the plant kingdom.[5]

Taxonomy

Two varieties of Morus alba are recognized:[3]

- Morus alba var. alba

- Morus alba var. multicaulis

Cultivation

Cultivation of white mulberry for silkworms began over four thousand years ago in China. In 2002, 6,260 km2 of land were devoted to the species in China.[4]

The species is now extensively planted and widely naturalized throughout the warm temperate world. It has been grown widely from India[4] west through Afghanistan and Iran to southern Europe for over a thousand years for leaves to feed silkworms.[8]

More recently, it has become widely naturalized in urban areas of eastern North America, where it hybridizes readily with a locally native red mulberry (Morus rubra). There is now serious concern for the long-term genetic viability of red mulberry because of extensive hybridization in some areas.[9] As a result, it is listed as an invasive plant in parts of North America.[10]

Uses

White mulberry leaves are the preferred feedstock for silkworms, and are also cut for food for livestock (cattle, goats, etc.) in areas where dry seasons restrict the availability of ground vegetation. The fruit are also eaten, often dried or made into wine.[4][8]

In traditional Chinese medicine, the fruit is used to treat prematurely grey hair, to "tonify" the blood, and treat constipation and diabetes.[citation needed] The bark is used to treat cough, wheezing, edema, and to promote urination. It is also used to treat fever, headache, red dry and sore eyes.

For landscaping, a fruitless mulberry was developed from a clone for use in the production of silk in the U.S. The industry never materialized, but the mulberry variety is now used as an ornamental tree where shade is desired without the fruit.[11] A weeping cultivar of white mulberry, Morus alba 'Pendula', is a popular ornamental plant.[10]

Medical uses

Dental caries: The root bark of Morus alba (Moraceae) has been used as a traditional medicine in Asian countries and exhibits antibacterial activity against food poisoning micro-organisms. Using activity against S. mutans in bioassay-guided fractionation of a methanol extract of dried root bark, and organic solvent fractions of this extract, the active antibacterial constituent was identified as kuwanon G. The compound displayed an MIC of 8 μg ml–1 against S. mutans, which was comparable to chlorhexidine and vancomycin (1 μg ml–1). Time-kill assays indicated that S. mutans was completely inactivated by 20 μg ml–1 kuwanon G within 1 min, while testing against other bacteria suggested that the compound displayed preferential antimicrobial activity against cariogenic bacteria. Electron microscopic examination of S. mutans cells treated with kuwanon G indicated that the mode of antibacterial action was inhibition or blocking of cell growth, as treated cells showed a disintegrated surface and an unclear cell margin.[12]

Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects from freeze-dried powder of mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruit[13]

Neuroprotective effects in in vitro and in vivo (fruit) [14]

Albanol A, isolated from the root bark extract of M. alba, may be a promising lead compound for developing an effective drug for treatment of leukemia.[15]

Moracin M, steppogenin-4′-O-β-D-glucoside and mulberroside A were isolated from the root bark of Morus alba L. and all produced hypoglycemic effects.[16] Mulberroside A, a glycosylated stilbenoid, can be useful in the treatment of hyperuricemia and gout[17][18]

A methanol extract of Morus alba roots showed adaptogenic activity, indicating its possible clinical utility as an antistress agent.[19]

Morus alba leaf extract help restore the vascular reactivity of diabetic rats. Free radical-induced vascular dysfunction plays a key role in the pathogenesis of vascular disease found in chronic diabetic patients.[20]

An ethanolic extract of mulberry leaf had antihyperglycemic, antioxidant and antiglycation effects in chronic diabetic rats, which may suggest its use as food supplement for diabetics.[21]

Other uses

An acidified methanolic extract of the fruit of Morus alba can be used as an acid-base indicator in acid-base titrations. Titration shows sharp colour change at the equivalence point. This is a natural indicator that is useful, economical, simple and accurate for determining acids and bases.[22]

Snakebite[23] "Morus alba plant leaf extract has been studied against the Indian Vipera/Daboia russelii venom induced local and systemic effects. The extract completely abolished the in vitro proteolytic and hyaluronolytic activities of the venom. Edema, hemorrhage and myonecrotic activities were also neutralized efficiently. In addition, the extract partially inhibited the pro-coagulant activity and completely abolished the degradation of A α chain of human fibrinogen. Thus, the extract processes potent antisnake venom property, especially against the local and systemic effects of Daboia russelii venom."

In culture

An etiological Babylonian story that was later incorporated into Greek and Roman mythology attributes the reddish purple color of the white mulberry (Morus alba) fruits to the tragic deaths of the lovers Pyramus and Thisbe.

The "White Mulberry Tree" is title of a crucial chapter in Willa Cather's 1913 novel, O Pioneers!, in which two forbidden lovers are killed, a reference to the story of Pyramus and Thisbe.

Gallery

-

Fruitless mulberry trees

-

Pennsylvania state champion Morus alba at Longwood Gardens.

-

Leaves and fruit - notice small seeds on the upper leaves

-

Leaves and flowers in the spring.

-

Unripe fruit.

References

- ↑ Zhengyi Wu, Zhe-Kun Zhou & Michael G. Gilbert (2013). "Morus alba var. alba". eFloras. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ Zhengyi Wu, Zhe-Kun Zhou & Michael G. Gilbert (2013). "Morus alba var. multicaulis". Flora of China. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Zhengyi Wu, Zhe-Kun Zhou & Michael G. Gilbert (2013). "Morus alba". eFloras. Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA. Retrieved 27 June 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Suttie, J. M. (undated). FAO Report: Morus alba L.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Taylor, Philip; Gwyneth Card, James House, Michael Dickinson, Richard Flagan (2006-03-01). "High-speed pollen release in the white mulberry tree, Morus alba L". Sexual Plant Reproduction 19 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1007/s00497-005-0018-9.

- ↑ Schaffner, John H. 1919. The nature of the diecious condition in Morus alba and Salix amygdaloides. Ohio Journal of Science 18: 101-125.

- ↑ Purdue University. Center for New Crops & Plant Products. NewCROP: Morus alba.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bean, W. J. (1978). Trees and Shrubs Hardy in the British Isles. John Murray ISBN 0-7195-2256-0.

- ↑ Burgess, K.S., Morgan, M., Deverno, L., & Husband, B. C. (2005). Asymmetrical introgression between two Morus species (M. alba, M. rubra) that differ in abundance. Molec. Ecol. 14: 3471–3483.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Morus alba L. USDA Plants Profile

- ↑ Howstuffworks.com

- ↑ "Kuwanon G: an antibacterial agent from the root bark of Morus alba against oral pathogens"

- ↑ Hypolipidemic and antioxidant effects of mulberry (Morus alba L.) fruit in hyperlipidaemia rats Yang X., Yang L., Zheng H. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2010 48:8-9 (2374-2379)

- ↑ Mulberry fruit protects dopaminergic neurons in toxin-induced Parkinson's disease models. Kim H.G., Ju M.S., Shim J.S., Kim M.C., Lee S.H., Huh Y., Kim S.Y., Oh M.S. The British journal of nutrition 2010 104:1 (8-16)

- ↑ Albanol a from the root bark of Morus alba L. induces apoptotic cell death in HL60 human leukemia cell line Kikuchi T., Nihei M., Nagai H., Fukushi H., Tabata K., Suzuki T., Akihisa T. Chemical and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2010 58:4 (568-571)

- ↑ In vivo hypoglycemic effects of phenolics from the root bark of Morus alba Zhang M., Chen M., Zhang H.-Q., Sun S., Xia B., Wu F.-H. Fitoterapia 2009 80:8 (475-477)

- ↑ Mulberroside A Possesses Potent Uricosuric and Nephroprotective Effects in Hyperuricemic Mice Wang C.-P., Wang Y., Wang X., Zhang X., Ye J.-F., Hu L.-S., Kong L.-D. [Article in Press] Planta Medica 2010

- ↑ Kim, JK; Kim, M; Cho, SG; Kim, MK; Kim, SW; Lim, YH (2010). "Biotransformation of mulberroside a from Morus alba results in enhancement of tyrosinase inhibition". Journal of industrial microbiology & biotechnology 37 (6): 631–7. doi:10.1007/s10295-010-0722-9. PMID 20411402.

- ↑ Adaptogenic effect of Morus alba on chronic footshock-induced stress in rats Nade V.S., Kawale L.A., Naik R.A., Yadav A.V. Indian Journal of Pharmacology 2009 41:6

- ↑ Mulberry leaf extract restores arterial pressure in streptozotocin-induced chronic diabetic rats Naowaboot J., Pannangpetch P., Kukongviriyapan V., Kukongviriyapan U., Nakmareong S., Itharat A. Nutrition Research 2009 29:8 (602-608)

- ↑ Antihyperglycemic, antioxidant and antiglycation activities of mulberry leaf extract in streptozotocin-induced chronic diabetic rats Naowaboot J., Pannangpetch P., Kukongviriyapan V., Kongyingyoes B., Kukongviriyapan U. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2009 64:2 (116-121)

- ↑ Morus alba fruit- herbal alternative to synthetic acid base indicators Pathade K.S., Patil S.B., Kondawar M.S., Naikwade N.S., Magdum C.S. International Journal of ChemTech Research 2009 1:3

- ↑ Neutralization of local and systemic toxicity of Daboia russelii venom by Morus alba plant leaf extract Chandrashekara K.T., Nagaraju S., Usha Nandini S., Basavaiah , Kemparaju K. Phytotherapy Research 2009 23:8 (1082-1087)

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Morus alba |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morus alba. |

- U.S. Forest Service Invasive Species Weed of the Week

- USDA GRIN White Mulberry

- Diagnostic photos, Morton Arboretum acc. 380*82-1

- USDA NRCS Plants Profile, Morus alba