Mughal Empire

| Mughal Empire گورکانیان (Persian) Gūrkāniyān مغلیہ سلطنت (Urdu) Mug̱ẖliyah Salṭanat | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

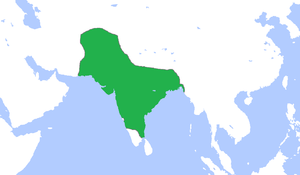

The Mughal Empire during the reign of Aurangzeb c. 1700 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Agra (1526–1571) Fatehpur Sikri (1571–1585) Lahore (1585–1598) Agra (1598–1648) Shahjahanabad/Delhi (1648–1857) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Persian (official and court language)[4] Chagatai Turkic (only initially) Urdu (later period) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Islam (1526–1582) Din-e Ilahi (1582–1605) Islam (1605–1857) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy, unitary state with federal structure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1526–1530 | Babur (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1837–1857 | Bahadur Shah II (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | Battle of Panipat | 21 April 1526 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | Siege of Delhi | 21 September 1857 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| - | 1700[lower-alpha 1] est. | 150,000,000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density | 33.3 /km² (86.3 /sq mi) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Rupee | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Mughal Empire (Urdu: مغلیہ سلطنت, Mug̱ẖliyah Salṭanat),[6] self-designated as Gurkani (Persian: گورکانیان, Gūrkāniyān),[7] was an empire extending over large parts of the Indian subcontinent and ruled by a dynasty of Chagatai-Turkic origin.[8][9][10]

In the early 16th century, northern India, being then under mainly Muslim rulers,[11] fell to the superior mobility and firepower of the Mughals.[12] The resulting Mughal Empire did not stamp out the local societies it came to rule, but rather balanced and pacified them through new administrative practices[13][14] and diverse and inclusive ruling elites,[15] leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule.[16] Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic identity, especially under Akbar, the Mughals united their far-flung realms through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status.[15] The Mughal state's economic policies, deriving most revenues from agriculture[17] and mandating that taxes be paid in the well-regulated silver currency,[18] caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets.[16] The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion,[16] resulting in greater patronage of painting, literary forms, textiles, and architecture.[19] Newly coherent social groups in northern and western India, such as the Marathas, the Rajputs, and the Sikhs, gained military and governing ambitions during Mughal rule, which, through collaboration or adversity, gave them both recognition and military experience.[20] Expanding commerce during Mughal rule gave rise to new Indian commercial and political elites along the coasts of southern and eastern India.[20] As the empire disintegrated, many among these elites were able to seek and control their own affairs.[21]

The beginning of the empire is conventionally dated to the founder Babur's victory over Ibrahim Lodi in the first Battle of Panipat (1526). It reached its peak extent under Aurangzeb, and declined rapidly after his death (in 1707) under a series of ineffective rulers. The empire's collapse followed heavy losses inflicted by the smaller army of the Maratha Empire in the Deccan Wars,[22] which encouraged the Nawabs of Bengal, Bhopal, Oudh, Carnatic, Rampur, the Nizam of Hyderabad and the Shah of Afghanistan to declare their independence from the Mughals.[23] Following the Third Anglo-Maratha war in 1818, the emperor became a pensioner of the Raj, and the empire, its power now limited to Delhi, lingered on until 1857, when it was effectively dissolved after the fall of Delhi during the Indian Rebellion that same year.[24]

The Mughal emperors were Central Asian Turko-Mongols from modern-day Uzbekistan, who claimed direct descent from both Genghis Khan (through his son Chagatai Khan) and Timur. At the height of their power in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, they controlled much of the Indian subcontinent, extending from Bengal in the east to Kabul & Sindh in the west, Kashmir in the north to the Kaveri basin in the south.[25] Its population at that time has been estimated as between 110 and 150 million(quarter of the world's population), over a territory of more than 3.2 million square kilometres (1.2 million square miles).[1]

The "classic period" of the empire started in 1556 with the ascension of Akbar the Great to the throne. Under the rule of Akbar and his son Jahangir, India enjoyed economic progress as well as religious harmony, and the monarchs were interested in local religious and cultural traditions. Akbar was a successful warrior. He also forged alliances with several Hindu Rajput kingdoms. Some Rajput kingdoms continued to pose a significant threat to Mughal dominance of northwestern India, but they were subdued by Akbar. Most Mughal emperors were Muslims. However Akbar in the latter part of his life, and Jahangir, were followers of a new religion called Deen-i-Ilahi, as recorded in historical books like Ain-e-Akbari & Dabestan-e Mazaheb.[26]

The reign of Shah Jahan, the fifth emperor, was the golden age of Mughal architecture. He erected several large monuments, the most famous of which is the Taj Mahal at Agra, as well as the Moti Masjid, Agra, the Red Fort, the Jama Masjid, Delhi, and the Lahore Fort. The Mughal Empire reached the zenith of its territorial expanse during the reign of Aurangzeb and also started its terminal decline in his reign due to Maratha military resurgence under Shivaji Bhosale. During his lifetime, victories in the south expanded the Mughal Empire to more than 1.25 million square miles, ruling over more than 150 million subjects, nearly 1/4th of the world's population, with a combined GDP of over $90 billion.[1][27]

By the mid-18th century, the Marathas had routed Moghul armies, and won over several Mughal provinces from the Deccan to Bengal, and internal dissatisfaction arose due to the weakness of the Mughal Empire's administrative and economic systems, leading to the declaration of independence by the Nawabs of Bengal, Bhopal, Oudh, Carnatic, Rampur, the Nizam of Hyderabad and Shah of Afghanistan. In 1739, the Mughals were defeated in the Battle of Karnal by the forces of Nader Shah. Mughal power was severely limited and the last emperor, Bahadur Shah II had authority over only the city of Shahjahanabad. He issued a firman supporting the Indian Rebellion of 1857 and was therefore tried by the British for treason, imprisoned, exiled to Rangoon and the last remnants of the empire were taken over by the British Raj.

Etymology

Contemporaries referred to the empire founded by Babur as the Timurid empire,[28] which reflected the heritage of his dynasty, and was the term preferred by the Mughals themselves.[29] Another name was Hindustan, which was documented in the Ain-i-Akbari, and which has been described as the closest to an official name for the empire.[30] In the west, the term “Mughal” was used for the emperor, and by extension, the empire as a whole.[31] The use of Mughal, deriving from the Arabic and Persian corruption of Mongol, and emphasising the Mongol origins of the Timurid dynasty,[32] gained currency during the nineteenth century, but remains disputed by Indologists.[33] Babur's ancestors were sharply distinguished from the classical Mongols insofar as they were oriented towards Persian rather than Turko-Mongol culture.[34]

History

The Mughal Empire was founded by Babur, a Central Asian ruler who was descended from the Turko-Mongol conqueror Timur on his father’s side and from Chagatai, the second son of the Mongol ruler Genghis Khan, on his mother’s side.[35] Ousted from his ancestral domains in Central Asia, Babur turned to India to satisfy his ambitions. He established himself in Kabul and then pushed steadily southward into India from Afghanistan through the Khyber Pass.[35] Babur's forces occupied much of northern India after his victory at Panipat in 1526.[35] The preoccupation with wars and military campaigns, however, did not allow the new emperor to consolidate the gains he had made in India.[35] The instability of the empire became evident under his son, Humayun, who was driven out of India and into Persia by rebels.[35] Humayun's exile in Persia established diplomatic ties between the Safavid and Mughal Courts, and led to closer cultural contacts between India and Iran. The restoration of Mughal rule began after Humayun’s triumphant return from Persia in 1555, but he died from a fatal accident shortly afterwards.[35] Humayun's son, Akbar, succeeded to the throne under a regent, Bairam Khan, who helped consolidate the Mughal Empire in India.[35]

Through warfare and diplomacy, Akbar was able to extend the empire in all directions and controlled almost the entire Indian subcontinent north of the Godavari river. He created a new class of nobility loyal to him from the military aristocracy of India's social groups, implemented a modern government, and supported cultural developments.[35] At the same time, Akbar intensified trade with European trading companies. India developed a strong and stable economy, leading to commercial expansion and economic development. Akbar allowed free expression of religion, and attempted to resolve socio-political and cultural differences in his empire by establishing a new religion, Din-i-Ilahi, with strong characteristics of a ruler cult.[35] He left his successors an internally stable state, which was in the midst of its golden age, but before long signs of political weakness would emerge.[35] Akbar's son, Jahangir, ruled the empire at its peak, but he was addicted to opium, neglected the affairs of the state, and came under the influence of rival court cliques.[35] During the reign of Jahangir's son, Shah Jahan, the culture and splendour of the luxurious Mughal court reached its zenith as exemplified by the Taj Mahal.[35] The maintenance of the court, at this time, began to cost more than the revenue.[35]

Shah Jahan's eldest son, the liberal Dara Shikoh, became regent in 1658, as a result of his father's illness. However, a younger son, Aurangzeb, allied with the Islamic orthodoxy against his brother, who championed a syncretistic Hindu-Muslim culture, and ascended to the throne. Aurangzeb defeated Dara in 1659 and had him executed.[35] Although Shah Jahan fully recovered from his illness, Aurangzeb declared him incompetent to rule and had him imprisoned. During Aurangzeb reign, the empire gained political strength once more, but his religious conservatism and intolerance undermined the stability of Mughal society.[35] Aurangzeb expanded the empire to include almost the whole of South Asia, but at his death in 1707, many parts of the empire were in open revolt.[35] Aurangzeb's son, Shah Alam, repealed the religious policies of his father, and attempted to reform the administration. However, after his death in 1712, the Mughal dynasty sank into chaos and violent feuds. In the year 1719 alone, four emperors successively ascended the throne.[35]

During the reign of Muhammad Shah, the empire began to break up, and vast tracts of central India passed from Mughal to Maratha hands. The campaigns of Nadir Shah, who had earlier conquered Iran and Afghanistan, culminated with the Sack of Delhi and shattered the remnants of Mughal power and prestige.[35] Many of the empire's elites now sought to control their own affairs, and broke away to form independent kingdoms.[35] The Mughal Emperor, however, continued to be the highest manifestation of sovereignty. Not only the Muslim gentry, but the Maratha, Hindu, and Sikh leaders took part in ceremonial acknowledgements of the emperor as the sovereign of India.[36]

The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II made futile attempts to reverse the Mughal decline, and ultimately had to seek the protection of outside powers. In 1784, the Maratha's under Mahadji Scindia won acknowledgement as the protectors of the emperor in Delhi, a state of affairs that continued until after the Second Anglo-Maratha War. Thereafter, the British East India Company became the protectors of the Mughal dynasty in Delhi.[36] After a crushed rebellion which he nominally led in 1857-58, the last Mughal, Bahadur Shah Zafar, was deposed by the British government, who then assumed formal control of the country.[35]

List of Mughal emperors

| Emperor | Birth | Reign Period | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Babur | Feb 23, 1483 | 1526–1530 | Dec 26, 1530 | Was a direct descendant of Genghis Khan through Timur and was the founder of the Mughal Empire after his victories at the Battle of Panipat (1526) ad the Battle of Khanwa. |

| Humayun | Mar 6, 1508 | 1530–1540 | Jan 1556 | Reign interrupted by Suri Dynasty. Youth and inexperience at ascension led to his being regarded as a less effective ruler than usurper, Sher Shah Suri. |

| Sher Shah Suri | 1472 | 1540–1545 | May 1545 | Deposed Humayun and led the Suri Dynasty. |

| Islam Shah Suri | c.1500 | 1545–1554 | 1554 | 2nd and last ruler of the Suri Dynasty, claims of sons Sikandar and Adil Shah were eliminated by Humayun's restoration. |

| Humayun | Mar 6, 1508 | 1555–1556 | Jan 1556 | Restored rule was more unified and effective than initial reign of 1530–1540; left unified empire for his son, Akbar. |

| Akbar | Nov 14, 1542 | 1556–1605 | Oct 27, 1605 | He and Bairam Khan defeated Hemu during the Second Battle of Panipat and later won famous victories during the Siege of Chittorgarh and the Siege of Ranthambore; He greatly expanded the Empire and is regarded as the most illustrious ruler of the Mughal Empire as he set up the empire's various institutions; he married Mariam-uz-Zamani, a Rajput princess. One of his most famous construction marvels was the Lahore Fort. |

| Jahangir | Oct 1569 | 1605–1627 | 1627 | Jahangir set the precedent for sons rebelling against their emperor fathers. Opened first relations with the British East India Company. Reportedly was an alcoholic, and his wife Empress Noor Jahan became the real power behind the throne and competently ruled in his place. |

| Shah Jahan | Jan 5, 1592 | 1627–1658 | 1666 | Under him, Mughal art and architecture reached their zenith; constructed the Taj Mahal, Jama Masjid, Red Fort, Jahangir mausoleum, and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore. Deposed by his son Aurangzeb. |

| Aurangzeb | Oct 21, 1618 | 1658–1707 | Mar 3, 1707 | He reinterpreted Islamic law and presented the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri; he captured the diamond mines of the Sultanate of Golconda; he spent the major part of his last 27 years in the war with the Maratha rebels; at its zenith, his conquests expanded the empire to its greatest extent; the over-stretched empire was controlled by Mansabdars, and faced challenges after his death. He is known to have transcribed copies of the Qur'an using his own styles of calligraphy. he died during a campaign against the ravaging Marathas in the Deccan. |

| Bahadur Shah I | Oct 14, 1643 | 1707–1712 | Feb 1712 | First of the Mughal emperors to preside over an empire ravaged by uncontrollable revolts. After his reign, the empire went into steady decline due to the lack of leadership qualities among his immediate successors. |

| Jahandar Shah | 1664 | 1712–1713 | Feb 1713 | Was an unpopular incompetent titular figurehead; |

| Furrukhsiyar | 1683 | 1713–1719 | 1719 | His reign marked the ascendancy of the manipulative Syed Brothers, execution of the rebellious Banda In 1717 he granted a Firman to the English East India Company granting them duty free trading rights for Bengal, the Firman was repudiated by the notable Murshid Quli Khan. |

| Rafi Ul-Darjat | Unknown | 1719 | 1719 | |

| Rafi Ud-Daulat | Unknown | 1719 | 1719 | |

| Nikusiyar | Unknown | 1719 | 1743 | |

| Muhammad Ibrahim | Unknown | 1720 | 1744 | |

| Muhammad Shah | 1702 | 1719–1720, 1720–1748 | 1748 | Got rid of the Syed Brothers. Countered the emergence of the renegade Marathas and lost large tracts of Deccan and Malwa in the process. Suffered the invasion of Nadir-Shah of Persia in 1739.[37] |

| Ahmad Shah Bahadur | 1725 | 1748–54 | 1775 | |

| Alamgir II | 1699 | 1754–1759 | 1759 | The Mughal Empire had impulsively began to re-centralize after subjects anxiously sought his gratification, he was murdered according to the conspiracy of the unscrupulous Vizier Imad-ul-Mulk and his schismatic Maratha associate Sadashivrao Bhau; |

| Shah Jahan III | Unknown | In 1759 | 1772 | Was ordained to the imperial throne by Sadashivrao Bhau who went on to loot the Mughal heartlands, he was generally regarded as an usurper and was overthrown after the Third Battle of Panipat by Prince Mirza Jawan Bakht. |

| Shah Alam II | 1728 | 1759–1806 | 1806 | Was nominated as the Mughal Emperor by Ahmad Shah Durrani after the Third Battle of Panipat. Defeat of the combined forces of Mughal, Nawab of Oudh & Nawab of Bengal,Bihar at the hand of East India Company at the Battle of Buxar. Treaty of Allahabad. Hyder Ali becomes Nawab of Mysore in 1761. Ahmed-Shah-Abdali in 1761 defeated the Marathas during the Third Battle of Panipat; The fall of Tipu Sultan of Mysore in 1799; He was the last Mughal Emperor to preside effective control over the empire. |

| Akbar Shah II | 1760 | 1806–1837 | 1837 | He designated Mir Fateh Ali Khan Talpur as the new Nawab of Sindh, Although he was under British protection his imperial name was removed from the official coinage after a brief dispute with the British East India Company; |

| Bahadur Shah II | 1775 | 1837–1857 | 1862 | The last Mughal emperor was deposed by the British and exiled to Burma following the Indian Rebellion of 1857. End of Mughal dynasty. |

Influence on the Indian subcontinent

Mughal influence on South Asian art and culture

| Outline of South Asian history History of Indian subcontinent |

|---|

|

7000–3000 BC: Stone Age

|

|

3000–1300 BC: Bronze Age

|

|

1700–26 BC: Iron Age

|

|

21–1279 AD: Middle Kingdoms

|

|

1206–1596: Late medieval age

|

|

1526–1858: Early modern period

|

|

1505–1961: Colonial period

|

|

Other states (1102–1947)

|

|

Kingdoms of Sri Lanka

|

|

Nation histories

|

|

Regional histories |

A major Mughal contribution to the Indian subcontinent was their unique architecture. Many monuments were built by the Muslim emperors, especially Shahjahan, during the Mughal era including the UNESCO World Heritage Site Taj Mahal, which is known to be one of the finer examples of Mughal architecture. Other World Heritage Sites include Humayun's Tomb, Fatehpur Sikri, the Red Fort, the Agra Fort, and the Lahore Fort The palaces, tombs, and forts built by the dynasty stands today in Agra, Aurangabad, Delhi, Dhaka, Fatehpur Sikri, Jaipur, Lahore, Kabul, Sheikhupura, and many other cities of India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh.[38] With few memories of Central Asia, Babur's descendents absorbed traits and customs of the South Asia,[39] and became more or less naturalised.

Mughal influence can be seen in cultural contributions such as:[citation needed]

- Centralised, imperialistic government which brought together many smaller kingdoms.[40]

- Persian art and culture amalgamated with Indian art and culture.[41]

- New trade routes to Arab and Turkic lands.

- The development of Mughlai cuisine.[42]

- Mughal Architecture found its way into local Indian architecture, most conspicuously in the palaces built by Rajputs and Sikh rulers.

- Landscape gardening

Although the land the Mughals once ruled has separated into what is now India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Afghanistan, their influence can still be seen widely today. Tombs of the emperors are spread throughout India, Afghanistan,[43] and Pakistan.

The Mughal artistic tradition was eclectic, borrowing from the European Renaissance as well as from Persian and Indian sources. Kumar concludes, "The Mughal painters borrowed individual motifs and certain naturalistic effects from Renaissance and Mannerist painting, but their structuring principle was derived from Indian and Persian traditions."[44]

Urdu language

Although Persian was the dominant and "official" language of the empire, the language of the elite later evolved into a form known as Urdu. Highly Persianized and also influenced by Arabic and Turkic, the language was written in a type of Perso-Arabic script known as Nastaliq, and with literary conventions and specialized vocabulary being retained from Persian, Arabic and Turkic; the new dialect was eventually given its own name of Urdu. Compared with Hindi, the Urdu language draws more vocabulary from Persian and Arabic (via Persian) and (to a much lesser degree) from Turkic languages where Hindi draws vocabulary from Sanskrit more heavily.[45] Modern Hindi, which uses Sanskrit-based vocabulary along with Urdu loan words from Persian and Arabic, is mutually intelligible with Urdu.[46] Today, Urdu is the national language of Pakistan and also an important co-official language in India.

Mughal society

The Indian economy remained as prosperous under the Mughals as it was, because of the creation of a road system and a uniform currency, together with the unification of the country.[47] Manufactured goods and peasant-grown cash crops were sold throughout the world. Key industries included shipbuilding (the Indian shipbuilding industry was as advanced as the European, and Indians sold ships to European firms), textiles, and steel. The Mughals maintained a small fleet, which merely carried pilgrims to Mecca, imported a few Arab horses in Surat. Debal in Sindh was mostly autonomous. The Mughals also maintained various river fleets of Dhows, which transported soldiers over rivers and fought rebels. Among its admirals were Yahya Saleh, Munnawar Khan, and Muhammad Saleh Kamboh. The Mughals also protected the Siddis of Janjira. Its sailors were renowned and often voyaged to China and the East African Swahili Coast, together with some Mughal subjects carrying out private-sector trade.

Cities and towns boomed under the Mughals; however, for the most part, they were military and political centres, not manufacturing or commerce centres.[48] Only those guilds which produced goods for the bureaucracy made goods in the towns; most industry was based in rural areas. The Mughals also built Maktabs in every province under their authority, where youth were taught the Quran and Islamic law such as the Fatawa-e-Alamgiri in their indigenous languages.

The Bengal region was especially prosperous from the time of its takeover by the Mughals in 1590 to the seizure of control by the British East India Company in 1757.[49] In a system where most wealth was hoarded by the elites, wages were low for manual labour. Slavery was limited largely to household servants. However some religious cults proudly asserted a high status for manual labour.[50]

The nobility was a heterogeneous body; while it primarily consisted of Rajput aristocrats and foreigners from Muslim countries, people of all castes and nationalities could gain a title from the emperor. The middle class of openly affluent traders consisted of a few wealthy merchants living in the coastal towns; the bulk of the merchants pretended to be poor to avoid taxation. The bulk of the people were poor. The standard of living of the poor was as low as, or somewhat higher than, the standard of living of the Indian poor under the British Raj; whatever benefits the British brought with canals and modern industry were neutralized by rising population growth, high taxes, and the collapse of traditional industry in the nineteenth century.[citation needed]

Science and technology

Astronomy

While there appears to have been little concern for theoretical astronomy, Mughal astronomers continued to make advances in observational astronomy and produced nearly a hundred Zij treatises. Humayun built a personal observatory near Delhi. The instruments and observational techniques used at the Mughal observatories were mainly derived from the Islamic tradition.[51][52] In particular, one of the most remarkable astronomical instruments invented in Mughal India is the seamless celestial globe.

Alchemy

Sake Dean Mahomed had learned much of Mughal Alchemy and understood the techniques used to produce various alkali and soaps to produce shampoo. He was also a notable writer who described the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and the cities of Allahabad and Delhi in rich detail and also made note of the glories of the Mughal Empire.

Sake Dean Mahomed was appointed as shampooing surgeon to both Kings George IV and William IV.[53]

Technology

Fathullah Shirazi (c. 1582), a Persian polymath and mechanical engineer who worked for Akbar, developed a volley gun.[54]

Akbar was the first to initiate and utilize metal cylinder rockets known as bans particularly against War elephants, during the Battle of Sanbal.[55]

In the year 1657, the Mughal Army utilized rockets during the Siege of Bidar.[56] Prince Aurangzeb's forces discharged rockets and grenades while scaling the walls. Sidi Marjan himself was mortally wounded after a rocket struck his large gunpowder depot and after twenty-seven day's of hard fighting Bidar was captured by the victorious Mughals.[56]

Later onward's the Mysorean rockets were upgraded versions of Mughal rockets utilized during the Siege of Jinji by the progeny of the Nawab of Arcot. Hyder Ali's father Fatah Muhammad the constable at Budikote, commanded a corps consisting of 50 rocketmen (Cushoon) for the Nawab of Arcot. Hyder Ali realized the importance of rockets and introduced advanced versions of metal cylinder rockets. These rockets turned fortunes in favor of the Sultanate of Mysore during the Second Anglo-Mysore War particularly during the Battle of Pollilur.[57]

Gallery

-

The Bazaar outside the Wazir Khan Mosque in Lahore.

-

A Mughal War elephant guarding the gateway to the Grand Mosque in Mathura.

-

A depiction of the Taj Mahal.

-

Mughal troopers purchase copper utensils in the Bazaar.

See also

- Technology in the Mughal Empire

- Mughal (tribe)

- Mughal cuisine, a style of cooking

- Mughal gardens, a style of gardens

- Mughal painting, a style of painting

- Mughal weapons

- Mughal-e-Azam, an India film

- Mirza Mughal, fifth son of Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor

- Muslim conquest in the Indian subcontinent

- Mongols, one of several ethnic groups

- Persianate states

- Persians in the Mughal Empire

- Turco-Persian/Turco-Mongol

- List of the Muslim Empires

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

- Islamic architecture

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Richards, John F. (March 18, 1993). Johnson, Gordon; Bayly, C. A., eds. The Mughal Empire. The New Cambridge history of India: 1.5. I. The Mughals and their Contemporaries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1, 190. doi:10.2277/0521251192. ISBN 978-0521251198.

- ↑ Savage-Smith, Emilie (1985), Islamicate Celestial Globes: Their History, Construction, and Use, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Kazi, Najma (24 November 2007). "Seeking Seamless Scientific Wonders: Review of Emilie Savage-Smith's Work". FSTC Limited. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- ↑ Conan, Michel (2007). Middle East Garden Traditions: Unity and Diversity : Questions, Methods and Resources in a Multicultural Perspective, Volume 31. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. p. 235. ISBN 978-0884023296.

- ↑ The title (Mirza) descends to all the sons of the family, without exception. In the Royal family it is placed after the name instead of before it, thus, Abbas Mirza and Hosfiein Mirza. Mirza is a civil title, and Khan is a military one. The title of Khan is creative, but not hereditary. pg 601 Monthly magazine and British register, Volume 34 Publisher Printed for Sir Richard Phillips, 1812 Original from Harvard University

- ↑ Balfour, E.G. (1976). Encyclopaedia Asiatica: Comprising Indian-subcontinent, Eastern and Southern Asia. New Delhi: Cosmo Publications. S. 460, S. 488, S. 897. ISBN 978-8170203254.

- ↑ Zahir ud-Din Mohammad (September 10, 2002). Thackston, Wheeler M., ed. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. New York: Modern Library. p. xlvi. ISBN 978-0375761379. "In India the dynasty always called itself Gurkani, after Temür's title Gurkân, the Persianized form of the Mongolian kürägän, 'son-in-law,' a title he assumed after his marriage to a Genghisid princess."

- ↑ Richards, John F. (1995), The Mughal Empire, Cambridge University Press, p. 6, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2, retrieved 31 July 2013

- ↑ Schimmel, Annemarie (2004), The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture, Reaktion Books, p. 22, ISBN 978-1-86189-185-3, retrieved 31 July 2013

- ↑ Balabanlilar, Lisa (15 January 2012), Imperial Identity in Mughal Empire: Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern Central Asia, I.B.Tauris, p. 2, ISBN 978-1-84885-726-1, retrieved 31 July 2013

- ↑ Robb 2001, p. 80.

- ↑ Stein 1998, p. 164.

- ↑ Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 115.

- ↑ Robb 2001, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, p. 17.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 152.

- ↑ Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 158.

- ↑ Stein 1998, p. 169.

- ↑ Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 186.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Metcalf & Metcalf 2006, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Asher & Talbot 2008, p. 256.

- ↑ Kincaid, Dennis (1937). The Grand Rebel: An Impression of Shivaji, Founder of the Maratha Empire. London: Collins. pp. 72–78, 121–125.

- ↑ Brown, Katherine Butler (January 2007). "Did Aurangzeb Ban Music? Questions for the Historiography of his Reign". Modern Asian Studies 41 (1): 79. doi:10.1017/S0026749X05002313.

- ↑ Wilson Hunter, Sir William. The Indian Empire: Its People, History, and Products. p. 315.

- ↑ Chandra, Satish. Medieval India: From Sultanate To The Mughals. p. 202.

- ↑ Roy Choudhury, Makhan Lal. The Din-i-Ilahi:Or, The Religion of Akbar.

- ↑ Warrior Empire: The Mughals (DVD). The History Channel. October 31, 2006.

- ↑ Bose, Sugata Bose; Ayesha Jalal (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy. Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 978-0203712535.

- ↑ Avari, Burjor (2004). Islamic Civilization in South Asia: A History of Muslim Power and Presence in the Indian Subcontinent. Routledge. p. 83. ISBN 978-0415580618.

- ↑ Vanina, Eugenia (2012). Medieval Indian Mindscapes: Space, Time, Society, Man. Primus Books. p. 47. ISBN 978-9380607191.

- ↑ Fontana, Michela (2011). Matteo Ricci: A Jesuit in the Ming Court. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 32. ISBN 978-1442205888.

- ↑ Dodgson, Marshall G. S. islamologists (2009). The Venture of Islam, Volume 3: The Gunpowder Empires and Modern Times, Volume 3. University of Chicago Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0226346885.

- ↑ Huskin, Frans Husken; Dick van der Meij (2004). Reading Asia: New Research in Asian Studies. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1136843778.

- ↑ Canfield, Robert L. (2002). Turko-Persia in Historical Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 2002. p. 20. ISBN 978-0521522915.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 35.5 35.6 35.7 35.8 35.9 35.10 35.11 35.12 35.13 35.14 35.15 35.16 35.17 35.18 35.19 Berndl, Klaus (2005). National Geographic visual history of the world. University of Michigan. pp. 318–320. ISBN 978-0521522915.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Bose, Sugata Bose; Ayesha Jalal (2004). Modern South Asia: History, Culture, Political Economy. Routledge. p. 41. ISBN 978-0203712535.

- ↑ S. N. Sen (2006). History Modern India. New Age International. pp. 11–13, 41–43. ISBN 8122417744.

- ↑ Ross Marlay, Clark D. Neher. 'Patriots and Tyrants: Ten Asian Leaders' pp.269 ISBN 0847684423

- ↑ "Indian History-Medieval-Mughal Period-AKBAR". Webindia123.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ Mughal Empire – MSN Encarta. Archived from the original on 2009-11-01.

- ↑ "Indo-Persian Literature Conference: SOAS: North Indian Literary Culture (1450–1650)". SOAS. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ "Mughlai Recipes, Mughlai Dishes – Cuisine, Mughlai Food". Indianfoodforever.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ "The garden of Bagh-e Babur : Tomb of the Mughal emperor". Afghanistan-photos.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ R. Siva Kumar, "Modern Indian Art: a Brief Overview," Art Journal (1999) 58#3 pp 14+.

- ↑ "A Brief Hindi – Urdu FAQ". sikmirza. Archived from the original on 2007-12-02. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "Urdu Dictionary Project is Under Threat : ALL THINGS PAKISTAN". Pakistaniat.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ John F. Richards, The Mughal Empire (1996) pp 185–204

- ↑ K. N. Chaudhuri, "Some Reflections on the Town and Country in Mughal India," Modern Asian Studies (1978) 12#1 pp. 77–96

- ↑ Tirthankar1 Roy, "Where is Bengal? Situating an Indian Region in the Early Modern World Economy," Past & Present (Nov 2011) 213#1 pp 115–146

- ↑ Shireen Moosvi, "The World of Labour in Mughal India (c.1500–1750)," International Review of Social History (Dec 2011) Supplement S, Vol. 56 Issue S19, pp 245–261

- ↑ Sharma, Virendra Nath (1995), Sawai Jai Singh and His Astronomy, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., pp. 8–9, ISBN 8120812565

- ↑ Baber, Zaheer (1996), The Science of Empire: Scientific Knowledge, Civilization, and Colonial Rule in India, State University of New York Press, pp. 82–9, ISBN 0791429199

- ↑ Teltscher, Kate (2000). "The Shampooing Surgeon and the Persian Prince: Two Indians in Early Nineteenth-century Britain". Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies, 1469-929X 2 (3): 409–23. doi:10.1080/13698010020019226.

- ↑ Bag, A. K. (2005). "Fathullah Shirazi: Cannon, Multi-barrel Gun and Yarghu". Indian Journal of History of Science (New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy) 40 (3): 431–436. ISSN 0019-5235.

- ↑ MughalistanSipahi (2010-06-19). "Islamic Mughal Empire: War Elephants Part 3". YouTube. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 The Mughal Empire – Ishwari Prasad – Google Books. Books.google.com.pk. Retrieved 2012-04-29.

- ↑ Roddam Narasimha (1985). "Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750–1850 A.D.". National Aerospace Laboratories, India. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

Further reading

<th class="" style=";padding:0.2em 0.4em 0.2em;;font-size:145%;line-height:1.2em;font family:Times New Roman;"">History of the Mongols |

| Timeline · History · States |

|

|

- Alam, Muzaffar. Crisis of Empire in Mughal North India: Awadh & the Punjab, 1707–48 (1988)

- Ali, M. Athar. "The Passing of Empire: The Mughal Case," Modern Asian Studies (1975) 9#3 pp. 385–396 in JSTOR, on the causes of its collapse

- Asher, C. B.; Talbot, C (1 January 2008), India Before Europe (1st ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-51750-8

- Black, Jeremy. "The Mughals Strike Twice," History Today (April 2012) 62#4 pp 22–26. full text online

- Blake, Stephen P. "The Patrimonial-Bureaucratic Empire of the Mughals," Journal of Asian Studies (1979) 39#1 pp. 77–94 in JSTOR

- Dale, Stephen F. The Muslim Empires of the Ottomans, Safavids and Mughals (Cambridge U.P. 2009)

- Dalrymple, William (2007). The Last Mughal: The Fall of a Dynasty : Delhi, 1857. Random House Digital, Inc.

- Faruqui, Munis D. "The Forgotten Prince: Mirza Hakim and the Formation of the Mughal Empire in India," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient (2005) 48#4 pp 487–523 in JSTOR, on Akbar and his brother

- Gommans; Jos. Mughal Warfare: Indian Frontiers and Highroads to Empire, 1500–1700 (Routledge, 2002) online edition

- Gordon, S. The New Cambridge History of India, II, 4: The Marathas 1600–1818 (Cambridge, 1993).

- Habib, Irfan. Atlas of the Mughal Empire: Political and Economic Maps (1982).

- Markovits, Claude, ed. (2004). A History of Modern India, 1480–1950. Anthem Press. pp. 79–184.

- Metcalf, B.; Metcalf, T. R. (9 October 2006), A Concise History of Modern India (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1

- Richards, John F. (1996). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1974). The Mughul Empire. B.V. Bhavan.

- Richards, John F. The Mughal Empire (The New Cambridge History of India) (1996) excerpt and online search

- Richards, J. F. "Mughal State Finance and the Premodern World Economy," Comparative Studies in Society and History (1981) 23#2 pp. 285–308 in JSTOR

- Robb, P. (2001), A History of India, London: Palgrave, ISBN 978-0-333-69129-8

- Stein, B. (16 June 1998), A History of India (1st ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-20546-3

- Stein, B. (27 April 2010), Arnold, D., ed., A History of India (2nd ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6

Culture

- Berinstain, V. Mughal India: Splendour of the Peacock Throne (London, 1998).

- Busch, Allison. Poetry of Kings: The Classical Hindi Literature of Mughal India (2011) excerpt and text search

- Preston, Diana and Michael Preston. Taj Mahal: Passion and Genius at the Heart of the Moghul Empire Walker & Company; ISBN 0802716733.

- Schimmel, Annemarie. The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture (Reaktion 2006)

- Welch, S.C. et al (1987). The Emperors' album: images of Mughal India. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870994999.

Society and economy

- Chaudhuri, K. N. "Some Reflections on the Town and Country in Mughal India," Modern Asian Studies (1978) 12#1 pp. 77–96 in JSTOR

- Habib, Irfan. Atlas of the Mughal Empire: Political and Economic Maps (1982).

- Habib, Irfan. Agrarian System of Mughal India (1963, revised edition 1999).

- Heesterman, J. C. "The Social Dynamics of the Mughal Empire: A Brief Introduction," Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, (2004) 47#3 pp. 292–297 in JSTOR

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam. "The Middle Classes in the Mughal Empire," Social Scientist (1976) 5#1 pp. 28–49 in JSTOR

- Rothermund, Dietmar. An Economic History of India: From Pre-Colonial Times to 1991 (1993)

Primary sources

- Bernier, Francois (1891). Travels in the Mogul Empire, A.D. 1656–1668. Archibald Constable, London.

- Hiro, Dilip, ed, Journal of Emperor Babur (Penguin Classics 2007)

- The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor ed. by W.M. Thackston Jr. (2002); this was the first autobiography in Islamic literature

- Jackson, A.V. et al., eds. History of India (1907) v.9. Historic accounts of India by foreign travellers, classic, oriental, and occidental, by A.V.W. Jackson online edition

- Jouher (1832). The Tezkereh al vakiat or Private Memoirs of the Moghul Emperor Humayun Written in the Persian language by Jouher A confidential domestic of His Majesty. Translated by Major Charles Stewart. John Murray, London.

Older histories

- Elliot, Sir H. M., Edited by Dowson, John. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians. The Muhammadan Period; published by London Trubner Company 1867–1877. (Online Copy at Packard Humanities Institute – Other Persian Texts in Translation; historical books: Author List and Title List)

- Adams, W. H. Davenport (1893). Warriors of the Crescent. London: Hutchinson.

- Holden, Edward Singleton (1895). The Mogul emperors of Hindustan, A.D. 1398- A.D. 1707. New York : C. Scribner's Sons.

- Malleson, G. B (1896). Akbar and the rise of the Mughal empire. Oxford : Clarendon Press.

- Manucci, Niccolao; tr. from French by François Catrou (1826). History of the Mogul dynasty in India, 1399–1657. London : J.M. Richardson.

- Lane-Poole, Stanley (1906). History of India: From Reign of Akbar the Great to the Fall of Moghul Empire (Vol. 4). London, Grolier society.

- Manucci, Niccolao; tr. by William Irvine (1907). Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653–1708, Vol. 1. London, J. Murray.

- Manucci, Niccolao; tr. by William Irvine (1907). Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653–1708, Vol. 2. London, J. Murray.

- Manucci, Niccolao; tr. by William Irvine (1907). Storia do Mogor; or, Mogul India 1653–1708, Vol. 3. London, J. Murray.

- Owen, Sidney J (1912). The Fall of the Mogul Empire. London, J. Murray.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mughal Empire. |

- Mughals and Swat

- Mughal India an interactive experience from the British Museum

- The Mughal Empire from BBC

- Mughal Empire

- The Great Mughals

- Gardens of the Mughal Empire

- Indo-Iranian Socio-Cultural Relations at Past, Present and Future, by M.Reza Pourjafar, Ali

- A. Taghvaee, in Web Journal on Cultural Patrimony (Fabio Maniscalco ed.), vol. 1, January–June 2006

- Adrian Fletcher's Paradoxplace — PHOTOS — Great Mughal Emperors of India

- A Mughal diamond on BBC

- Some Mughal coins with brief history

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||