Mogadishu

| Mogadishu Muqdisho (so) مقديشو (ar) Maqadīshū | |

|---|---|

| Capital | |

| |

| Nickname(s): Xamar (English: Hamar)[1] | |

Mogadishu | |

| Coordinates: 02°02′N 45°21′E / 2.033°N 45.350°ECoordinates: 02°02′N 45°21′E / 2.033°N 45.350°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Banaadir |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mohamed Nur |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,657 km2 (640 sq mi) |

| Population (2009) | |

| • Total | 1,353,000[2] |

| • Density | 817/km2 (2,120/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EAT (UTC+3) |

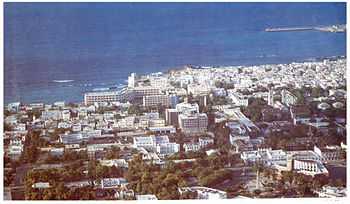

Mogadishu (/ˌmɔːɡəˈdiːʃuː/;[3][4] Somali: Muqdisho; Arabic: مقديشو Maqadīshū), known locally as Xamar (English: Hamar), is the largest city in Somalia and the nation's capital. Located in the coastal Banaadir region on the Indian Ocean, the city has served as an important port for centuries.

Tradition and old records assert that southern Somalia, including the Mogadishu area, was historically inhabited by hunter-gatherers of Khoisan physical stock. These were later joined by Cushitic agro-pastoralists, who would go on to establish local aristocracies.[5][6] Starting in the late 9th or 10th centuries, Arab and Persian traders also began to settle in the region.[7]

During its medieval Golden Age, Mogadishu was ruled by the Somali-Arab Muzaffar dynasty, a vassal of the Ajuuraan State.[8] It subsequently fell under the control of an assortment of local Sultanates and polities, most notably the Geledi Sultanate.[9] The city later became the capital of Italian Somaliland in the colonial period. Post-independence, it was known and promoted as the White Pearl of the Indian Ocean.[10]

After the ousting of the Siad Barre regime and the ensuing civil war, various militias fought for control of the city, later to be replaced by the Islamic Courts Union. The ICU thereafter splintered into more radical groups, notably Al Shabaab, which fought the Transitional Federal Government and its AMISOM allies. With a change in administration in late 2010, federal control of Mogadishu steadily expanded. The pace of territorial gains also greatly accelerated, as more trained government and AMISOM troops entered the city. In early August 2011, government troops and their AMISOM partners had succeeded in forcing out Al-Shabaab from the parts of the city that the group had previously controlled.[11] Mogadishu has subsequently experienced a period of intense reconstruction.[12]

Etymology

The name Mogadishu is held to be derived from the Persian مقعد شاه Maq'ad-i-Shah ("The seat of the Shah"), a reflection of the city's early Persian influence.[13] It is known locally as Xamar (English: Hamar).[1]

History

Early history

Tradition and old records assert that southern Somalia, including the Mogadishu area, was inhabited in early historic times by hunter-gatherers of Khoisan stock. Although most of these early inhabitants are believed to have been either overwhelmed, driven away or, in some cases, assimilated by later migrants to the area, physical traces of their occupation survive in certain ethnic minority groups inhabiting modern-day Jubaland and other parts of the south. The latter descendants include relict populations such as the Eile, Aweer, the Wa-Ribi, and especially the Wa-Boni.[5][6] By the time of the arrival of peoples from the Cushitic Rahanweyn (Digil and Mirifle) clan confederacy, who would go on to establish a local aristocracy, other Cushitic groups affiliated with the Oromo (Wardai) and Ajuuraan (Ma'adanle) had already formed settlements of their own in the sub-region.[5][6]

According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a Greek travel document dating from the turn of the Common Era, maritime trade already connected peoples in the Mogadishu area with other communities along the Indian Ocean coast.

_flag_according_to_1576_Portuguese_map.svg.png)

The Sultanate of Mogadishu later developed with the immigration of Emozeidi Arabs, a community whose earliest presence dates back to the 9th or 10th century.[7] This evolved into the Muzaffar dynasty, a joint Somali-Arab federation of rulers, and Mogadishu became closely linked with the powerful Somali Ajuuraan State.[8] Following his visit to the city, the 12th century Syrian historian Yaqut al-Hamawi wrote that it was inhabited by dark-skinned Berbers, the ancestors of the modern Somalis.[14][15]

For many years, Mogadishu stood as the pre-eminent city in the بلاد البربر Bilad-ul-Barbar ("Land of the Berbers"), which was the medieval Arabic term for the Horn of Africa.[16][17][18] By the time of the Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta's appearance on the Somali coast in 1331, the city was at the zenith of its prosperity. He described Mogadishu as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, which was famous for the high quality fabric that it exported to destinations including Egypt.[19][20] He added that the city was ruled by a Somali Sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Sayx 'Umar,[21][22] who was originally from Berbera in northern Somalia and spoke both Somali (referred to by Battuta as Mogadishan, the Benadir dialect of Somali) and Arabic with equal fluency.[22][23] The Sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and other officials at his beck and call.[22]

The Portuguese would later attempt to occupy the city, but never managed to take it. The Hawiye Somali, however, were successful in defeating the Ajuuraan State and bringing about the end of Muzaffar rule.[8]

1800s–1950s

By 1892, Mogadishu was under the joint control of the Somali Geledi Sultanate (which, also holding sway over the Shebelle region in the interior, was at the height of its power) and the Omani Sultan of Zanzibar.[9] In 1892, Ali bin Said leased the city to Italy. Italy purchased the city in 1905 and made Mogadishu the capital of the newly established Italian Somaliland. The Italians subsequently referred to the city as Mogadiscio. After World War I, the surrounding territory came under Italian control with some resistance.

Thousands of Italians settled in Mogadishu and founded small manufacturing companies. They also developed some agricultural areas in the south near the capital, such as Janale and the Villaggio duca degli Abruzzi (Jowhar).[24] In the 1930s, new buildings and avenues were built. A 114 km narrow-gauge railway was laid from Mogadishu to Jowhar, then called "Villaggio Duca degli Abruzzi". An asphalted road, the Strada Imperiale, was also constructed, intended to link Mogadishu to Addis Ababa.

In 1940, the Italo-Somali population numbered 22,000, accounting for over 44% of the city's population of 50,000 residents.[25][26] Mogadishu would remain the capital of Italian Somaliland throughout the latter polity's existence.

1960-1990

British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somaliland) followed suit five days later.[27] On July 1, 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic, with Mogadishu serving as the nation's capital. A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa and other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as President of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as President of the Somali Republic, and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister (later to become President from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution, which was first drafted in 1960.[28] In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke.

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état on 21 October 1969 (the day after his funeral), in which the Somali Army seized power without encountering armed opposition — essentially a bloodless takeover. The putsch was spearheaded by Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, who at the time commanded the army.[29]

Alongside Barre, the Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC) that assumed power after President Sharmarke's assassination was led by Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Korshel. Kediye officially held the title of "Father of the Revolution," and Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[30] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic,[31][32] arrested members of the former civilian government, banned political parties,[33] dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[34]

The revolutionary army established various large-scale public works programmes, including the Mogadishu Stadium. In addition to a nationalization programme of industry and land, the Mogadishu-based new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League in 1974.[35]

After fallout from the unsuccessful Ogaden campaign of the late 1970s, the Barre administration began arresting government and military officials under suspicion of participation in the abortive 1978 coup d'état.[36][37] Most of the people who had allegedly helped plot the putsch were summarily executed.[38] However, several officials managed to escape abroad and started to form the first of various dissident groups dedicated to ousting Barre's regime by force.[39]

Civil war

By the late 1980s, Barre's regime had become increasingly unpopular. The authorities became ever more totalitarian, and resistance movements, encouraged by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration, sprang up across the country. This eventually led in 1991 to the outbreak of the civil war, the toppling of Barre's government, and the disbandment of the Somali National Army. Many of the opposition groups subsequently began competing for influence in the power vacuum that followed the ouster of Barre's regime. Armed factions led by USC commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital.[40]

UN Security Council Resolution 733 and UN Security Council Resolution 746 led to the creation of UNOSOM I, the first stabilization mission in Somalia after the dissolution of the central government. United Nations Security Council Resolution 794 was unanimously passed on December 3, 1992, which approved a coalition of United Nations peacekeepers led by the United States. Forming the Unified Task Force (UNITAF), the alliance was tasked with assuring security until humanitarian efforts were transferred to the UN. Landing in 1993, the UN peacekeeping coalition started the two-year United Nations Operation in Somalia II (UNOSOM II) primarily in the south.[41]

Some of the militias that were then competing for power interpreted the UN troops' presence as a threat to their hegemony. Consequently, several gun battles took place in Mogadishu between local gunmen and peacekeepers. Among these was the Battle of Mogadishu of 1993, an unsuccessful attempt by US troops to apprehend faction leader Aidid. The UN soldiers eventually withdrew altogether from the country on March 3, 1995, having incurred more significant casualties.

In 2006, the Islamic Courts Union (ICU), an Islamist organization, assumed control of much of the southern part of the country and promptly imposed Shari'a law. The new Transitional Federal Government (TFG), established two years earlier, sought to re-establish its authority. With the assistance of Ethiopian troops, AMISOM peacekeepers and air support by the United States, it managed to drive out the rival ICU and solidify its rule.[42] On 8 January 2007, as the Battle of Ras Kamboni raged, TFG President and founder Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed, a former colonel in the Somali Army, entered Mogadishu for the first time since being elected to office. The government then relocated to Villa Somalia in Mogadishu from its interim location in Baidoa, marking the first time since the fall of the Barre regime in 1991 that the federal government controlled most of the country.[43]

Following this defeat, the Islamic Courts Union splintered into several different factions. Some of the more radical elements, including Al-Shabaab, regrouped to continue their insurgency against the TFG and oppose the Ethiopian military's presence in Somalia. Throughout 2007 and 2008, Al-Shabaab scored military victories, seizing control of key towns and ports in both central and southern Somalia. At the end of 2008, the group had captured Baidoa but not Mogadishu. By January 2009, Al-Shabaab and other militias had managed to force the Ethiopian troops to retreat, leaving behind an under-equipped African Union peacekeeping force to assist the Transitional Federal Government's troops.[44]

Between 31 May and 9 June 2008, representatives of Somalia's federal government and the moderate Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia (ARS) group of Islamist rebels participated in peace talks in Djibouti brokered by the UN. The conference ended with a signed agreement calling for the withdrawal of Ethiopian troops in exchange for the cessation of armed confrontation. Parliament was subsequently expanded to 550 seats to accommodate ARS members, which then elected a new president.[45] With the help of a small team of African Union troops, the coalition government also began a counteroffensive in February 2009 to retake control of the southern half of the country. To solidify its control of southern Somalia, the TFG formed an alliance with the Islamic Courts Union, other members of the Alliance for the Re-liberation of Somalia, and Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a, a moderate Sufi militia.[46]

In November 2010, a new technocratic government was elected to office, which enacted numerous reforms, especially in the security sector.[47] By August 2011, the new administration and its AMISOM allies had managed to capture all of Mogadishu from the Al-Shabaab militants.[11] Mogadishu has subsequently experienced a period of intense reconstruction spearheaded by the Somali diaspora, the municipal authorities, and Turkey, a historic ally of Somalia.[12][48]

Geography

Mogadishu is situated on the Indian Ocean coast of the Horn of Africa, in the Banaadir administrative region (gobol) in southeastern Somalia.[2] The region itself is coextensive with the city and is much smaller than the historical province of Benadir. The city is administratively divided into the districts of Abdiaziz, Bondhere, Daynile, Dharkenley, Hamar-Jajab, Hamar-Weyne, Heliwa, Hodan, Howl-Wadag, Karan, Shangani, Shibis, Waberi, Wadajir, Wardhigley and Yaqshid.[49] Features of the city include the Hamarwein old town, the Bakaara Market, and Gezira Beach. The sandy beaches of Mogadishu have vibrant coral reefs, and are prime real estate for the first tourist resorts in many years.[50]

The Shebelle River (Webiga Shabelle) rises in central Ethiopia and comes within 30 kilometers (19 mi) of the Indian Ocean near Mogadishu before turning southwestward. Usually dry during February and March, the river provides water essential for the cultivation of sugarcane, cotton, and bananas.

Climate

For a city situated so near the equator, Mogadishu has a relatively dry climate. It is classified as hot and semi-arid (Köppen climate classification BSh). Much of the land that the city lies upon is desert terrain. Annual rainfall is a low 427 millimetres (16.8 in), mostly occurring during the wet season.

Sunshine is abundant locally, averaging eight to ten hours a day year-round. It is lowest during the wet season, when there is some coastal fog and greater cloud coverage as warm air passes over the cool sea surface.

| Climate data for Mogadishu | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 37 (99) |

39 (102) |

42 (108) |

41 (106) |

40 (104) |

38 (100) |

42 (108) |

42 (108) |

37 (99) |

32 (90) |

41 (106) |

42 (108) |

42 (108) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.2 (86.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.9 (87.6) |

32.2 (90) |

31.2 (88.2) |

29.6 (85.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.8 (87.4) |

30.2 (86.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.4 (74.1) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.2 (75.6) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.9 (75) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 22 (72) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

22 (72) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

22 (72) |

21 (70) |

17 (63) |

| Rainfall mm (inches) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

8 (0.31) |

61 (2.4) |

61 (2.4) |

82 (3.23) |

64 (2.52) |

44 (1.73) |

25 (0.98) |

32 (1.26) |

43 (1.69) |

9 (0.35) |

429 (16.87) |

| Avg. rainy days | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 47 |

| % humidity | 78 | 78 | 77 | 77 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 81 | 81 | 80 | 79 | 79 | 79.3 |

| Source #1: Weltwetter Spiegel Online[51] | |||||||||||||

| Source #2: Weatherbase [52] | |||||||||||||

Government

Federal

The Transitional Federal Government (TFG) was the internationally recognized central government of Somalia between 2004 and 2012. Based in Mogadishu, it constituted the executive branch of government.

The Federal Government of Somalia was established on 20 August 2012, concurrent with the end of the TFG's interim mandate.[53] It represents the first permanent central government in the country since the start of the civil war.[53] The Federal Parliament of Somalia serves as the government's legislative branch.[54]

Municipal

Mogadishu's municipal government is currently led by Mayor Mohamud Ahmed Nur ("Tarsan"), a former Labour Party member and business advisor to Islington Council in London. Since taking office in 2010, Nur's administration in conjunction with the federal authorities enacted a number of reforms in a bid to improve the city's security and service delivery.[55]

Among these new development initiatives are a $100 million USD urban renewal project, the creation of garbage disposal and incineration plants, the launch of a city-wide clean up project, the creation of asphalt and cement plants, rehabilitation of the Town Hall and parliament buildings, reconstruction of the former Defence Ministry offices, reconstruction of correctional facilities, rehabilitation and construction of health facilities, establishment of a Police Training Center and a permanent base in Jasiira for the new Somali Armed Forces, rebuilding of the Somali Postal Service headquarters, and rehabilitation of public playgrounds in several districts.[56] In January 2014, the Banaadir administration also launched the House Numbering and Post Code System.[57]

Diplomatic missions

A number of countries maintain foreign embassies and consulates in Mogadishu. As of January 2014, these diplomatic missions include the embassies of Djibouti, Ethiopia, Sudan, Libya, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Iran, Uganda, Nigeria, the United Kingdom and Japan.[58]

Embassies that are scheduled to reopen in the city include those of Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Italy and South Korea.[58]

Economy

Mogadishu traditionally served as a commercial and financial centre. Before the importation of mass-produced cloth from Europe and America, the city's textiles were forwarded far and wide throughout the interior of the continent, as well as to the Arabian peninsula and as far as the Persian coast.[59]

Mogadishu's economy has grown rapidly since the city's pacification in mid 2011. The SomalFruit processing factory was reopened, as was the local Coca Cola factory, which was also refurbished.[56] In May 2012, the First Somali Bank was established in the capital, representing the first commercial bank to open in southern Somalia since 1991.[60] The Historic Central Bank was also regenerated, with the Moumin Business Center likewise under construction.[56]

The galvanization of Mogadishu's real estate sector was in part facilitated by the establishment of a local construction yard in November 2012 by the Municipality of Istanbul and the Turkish Red Crescent. With 50 construction trucks and machines imported from Turkey, the yard produces concrete, asphalt and paving stones for building projects. The Istanbul Municipality was also scheduled to bring in 100 specialists to accelerate the construction initiative, which ultimately aims to modernize the capital's infrastructure and serve it over the long-term.[61]

In mid-2012, Mogadishu concurrently held its first ever Technology, Entertainment, Design (TEDx) conference. The event was organized by the First Somali Bank to showcase improvements in business, development and security to potential Somali and international investors.[60] A second consecutive TEDx entrepreneurial conference was held the following year in the capital, highlighting new enterprises and commercial opportunities, including the establishment of the city's first dry cleaning business in several years.[62]

A number of large firms also have their headquarters in Mogadishu. Among these is the Trans-National Industrial Electricity and Gas Company, an energy conglomerate founded in 2010 that unites five major Somali companies from the trade, finance, security and telecommunications sectors.[63][64] Other firms based in the city include Hormuud Telecom, the largest telecommunications company in southern and central Somalia. Telcom is another telecommunications service provider that is centered in the capital.

Additionally, the Central Bank of Somalia, the national monetary authority, has its headquarters in Mogadishu.

Demographics

Mogadishu is a multi-ethnic city. Its original core population consisted of Bushmen aboriginals, and later Cushitic, Arab and Persian migrants.[6][7] During the Arab slave trade, many Bantu peoples were brought in for agricultural work from the market in Zanzibar. The mixture of these various groups produced the Benadiri or Reer Xamar (“People of Mogadishu”), a composite population unique to the larger Benadir region.[65] In the colonial period, European expatriates, primarily Italians, would also contribute to the city's cosmopolitan populace.

The main area of inhabitation of Bantu ethnic minorities in Somalia has historically been in village enclaves in the south, particularly between the Jubba and Shebelle river valleys as well as the Bakool and Bay regions. Beginning in the 1970s, more Bantus began moving to urban centres such as Mogadishu and Kismayo.[66] By the late 1980s, over 40 percent of Mogadishu's population consisted of individuals from ethnic minority groups.[67] The displacement caused by the onset of the civil war in the 1990s further increased the number of rural minorities migrating to urban areas. As a consequence of these movements, Mogadishu's traditional demographic makeup changed significantly over the years.[66]

Following a greatly improved security situation in the city in 2012, many Somali expatriates began returning to Mogadishu for investment opportunities and to take part in the ongoing post-conflict reconstruction process. Participating in the renovation of schools, hospitals, roads and other infrastructure, they have played a leading role in the capital's recovery and have also helped propel the local real estate market.[68]

Landmarks

Places of worship

Arba'a Rukun Mosque is one of the oldest Islamic places of worship in the capital. It was built circa 667 (1268/9 CE), concurrently with the Fakr ad-Din Mosque. Arba'a Rukun's mihrab contains an inscription dated from the same year, which commemorates the masjid's late founder, Khusra ibn Mubarak al-Shirazi (Khusrau ibn Muhammed).[69][70]

The Mosque of Islamic Solidarity was constructed in 1987 with financial support from the Saudi Fahd bin Abdul Aziz Al Saud Foundation. It is the main mosque in the city, and an iconic building in Somali society. From 1991, during the civil war, the mosque was closed down, but with the rise to power of the Islamic Courts Union, it was reopened in 2006. With a capacity of up to 10,000 worshippers, the Mosque of Islamic Solidarity is the single largest masjid in the Horn of Africa.

Additionally, the municipal authority is refurbishing the historic Central Mosque, situated downtown.[56]

The Mogadishu Cathedral was built in 1928 by the colonial authorities in Italian Somaliland. Known as the "Cattedrale di Mogadiscio", it was constructed in a Norman Gothic style, based on the Cefalù Cathedral in Cefalù, Sicily. The church served as the traditional seat of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Mogadiscio.[71] It later incurred significant damage during the civil war. In April 2013, after a visit to the site to inspect its condition, the Diocese of Mogadiscio announced plans to refurbish the building.[72]

Palaces

Villa Somalia is the official residential palace and principal workplace of the President of Somalia, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. It sits on high ground that overlooks the city on the Indian Ocean, with access to both the harbour and airport.[73]

The Governor's Palace of Mogadishu was the seat of the governor of Italian Somaliland, and then the administrator of the Trust Territory of Somalia.

Museums, libraries and theatres

The National Museum of Somalia was established after the independence in 1960, when the old Garesa Museum was turned into a National Museum. The National Museum was later moved in 1985, renamed to the Garesa Museum, and converted to a regional museum.[74][75] After shutting down, the National Museum later reopened. As of January 2014, it holds many culturally important artefacts, including old coins, bartering tools, traditional artwork, ancient weaponry and pottery items.[76]

The National Library of Somalia was established in 1975, and came under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education, Culture and Higher Education. In 1983, it held approximately 7,000 books, little in the way of historical and cultural archival material, and was open to the general public.[77] The National Library later closed down in the 1990s. In June 2013, the Heritage Institute for Policy Studies organized a shipment of 22,000 books from the United States to Somalia as part of an initiative to restock the library.[78] In December of the year, the Somali authorities officially launched a major project to rebuild the National Library. With Zainab Hassan serving as Director, the $1 million federal government funded initiative will see a new library complex built in the capital within six months. In preparation for the relaunch, 60,000 additional books from other Arab League states are expected to arrive.[79]

The National Theatre of Somalia opened in 1967 as an important cultural landmark in the national capital. It closed down after the start of the civil war in the early 1990s, but reopened in March 2012 after reconstruction.[80] In September 2013, the Somali federal government and its Chinese counterpart signed an official cooperation agreement in Mogadishu as part of a five-year national recovery plan in Somalia. The pact will see the Chinese authorities reconstruct the National Theatre of Somalia in addition to several other major infrastructural landmarks.[81]

Markets

Bakaara Market was created in late 1972 by the Barre administration. It served as an open market for the sale of goods and services, including produce and clothing. After the start of the civil war, the market was controlled by various militant groups, who used it as a base for their operations. Following Mogadishu's pacification in 2011, renovations resumed at the market. Shops were rehabilitated, selling everything from fruit and garments to building materials.[82] As in the rest of the city, Barkaara Market's real estate values have also risen considerably. As of 2013, the local Tabaarak firm was renting out a newly constructed warehouse at the market for $2,000 per month.[83]

Hotels

Mogadishu has a number of hotels, most of which were recently constructed. The city's many returning expatriates, investors and international community workers are among these establishments' main customers. To meet the growing demand, hotel representatives have also begun participating in international industry conferences, such as the Africa Hotel Investment Forum.[84]

Among the new hotels is the six floor Jazeera Palace Hotel. It was built in 2010 and officially opened in 2012. Situated within a 300m radius of the Aden Adde International Airport, it has a 70 room capacity with a 70% occupancy rate. The hotel expects to host over 1,000 visitors by 2015, for which it plans to construct a larger overall building and conference facilities.[84]

Other hotels in the city include the Amira Castle Hotel, Sahafi Hotel, Hotel Nasa-Hablod, Oriental Hotel, Hotel Guuleed, Hotel Shamo, Peace Hotel, Aran Guest House, Muna Hotel, Hotel Taleex, Hotel Towfiq, Benadir Hotel, Ambassador Hotel, Jazeera Palace Hotel, Kuwait Plaza Hotel, Safari Hotel Diplomat, Safari Guesthouse and Bin Ali Hotel.[85]

Education

Mogadishu is home to a number of scholastic institutions. As part of the government's urban renewal program, 100 schools across the capital are scheduled to be refurbished and reopened.[56]

The Somali National University (SNU) was established in the 1950s, during the trusteeship period. In 1973, its programmes and facilities were expanded. The SNU developed over the next 20 years into an expansive institution of higher learning, with 13 departments, 700 staff and over 15,000 students. On 14 November 2013, the Cabinet unanimously approved a federal government plan to reopen the Somali National University, which had been closed down in the early 1990s. The refurbishing initiative is expected to cost $3.6 million USD.[86]

Mogadishu University (MU) is a non-governmental university that is governed by a Board of Trustees and a University Council. It is the brainchild of a number of professors from the Somali National University as well as other Somali intellectuals. Financed by the Islamic Development Bank in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, as well as other donor institutions, the university counts hundreds of graduates from its seven faculties, some of whom continue on to pursue Master's degrees abroad thanks to a scholarship programme. Mogadishu University has established partnerships with several other academic institutions, including the University of Aalborg in Denmark, three universities in Egypt, seven universities in Sudan, the University of Djibouti, and two universities in Yemen. As of 2012, MU also has accreditation with the Board of the Intergovernmental Organization EDU.[87]

In 1999, the Somali Institute of Management and Administration (SIMAD) was co-established in Mogadishu by incumbent President of Somalia Hassan Sheikh Mohamud. The institution subsequently grew into the SIMAD University, with Mohamud acting as dean until 2010.[88] It offers a range of undergraduate courses in various fields, including economics, statistics, business, accountancy, technology, computer science, health sciences, education, law and public administration.[89]

Benadir University (BU) was established in 2002 with the intention of training doctors. It has since expanded into other fields. Another tertiary institution in the city is the Jamhuriya University of Science and Technology. The Turkish Boarding School was also established, with the Mogadishu Polytechnic Institute and Shabelle University campus likewise undergoing renovations. Additionally, a New Islamic University campus is being built.[56]

Sport

Mogadishu Stadium was constructed in 1978 during the Barre administration, with the assistance of Chinese engineers. The facility was mainly used for hosting sporting activities, such as the Somalia Cup and for football matches with teams from the Somalia League. Presidential addresses and political rallies, among other events, were also held there.[90] In September 2013, the Somali federal government and its Chinese counterpart signed an official cooperation agreement in Mogadishu as part of a five-year national recovery plan in Somalia. The pact will see the Chinese authorities reconstruct several major infrastructural landmarks, including the Mogadishu Stadium.[81]

The Konis Stadium is another one of the capital's major sporting facilities. In 2013, the Somali Football Federation launched a renovation project at the facility, during which artificial football turf contributed by FIFA was installed at the stadium. The Ex-Lujino basketball stadium in the Abdulaziz District also underwent a $10,000 rehabilitation, with funding provided by the local Hormuud Telecom firm.[91] Additionally, the municipal authority oversaw the reconstruction of the Banadir Stadium.[56]

Various national sporting bodies also have their headquarters in Mogadishu. Among these are the Somali Football Federation, Somali Olympic Committee and Somali Basketball Federation. The Somali Karate and Taekwondo Federation is likewise centered in the city, and manages the national Taekwondo team.[92]

Transportation

Road

Roads leading out of Mogadishu connect the city to other localities in Somalia as well as to neighbouring countries. The capital itself is cut into several grid layouts by an extensive road network, with streets supporting the flow of both vehicular and pedestrian traffic. In October 2013, major construction began on the 23 kilometer road leading to the airport. Overseen by Somali and Turkish engineers, the upgrade was completed in November and included lane demarcation. The road construction initiative was part of a larger agreement signed by the Somali and Turkish governments to establish Mogadishu and Istanbul as sister cities, and in the process bring all of Mogadishu's roads up to modern standards.[93]

In 2012-2013, Mogadishu's municipal authority began a project to install solar-powered street lights on all of the capital's major roads. With equipment imported from Norway, the initiative cost around $140,000 and lasted several months. The solar panels are expected to improve night-time visibility and enhance the city's overall aesthetic appeal.[94]

In June 2013, two new taxi companies also started offering road transportation to residents. Part of a fleet of over 100 vehicles, Mogadishu Taxi's trademark yellow cabs offer rides throughout the city at flat rates of $5. City Taxi, the firm's nearest competitor, charges the same flat rate, with plans to add new cabs to its fleet.[95]

In January 2014, the Banaadir administration launched a city-wide street naming, house numbering and postal codes project. Officially called the House Numbering and Post Code System, it is a joint initiative of the municipal authorities and Somali business community representatives. The project is part of the ongoing modernization and development of the capital. According to Mayor Mohamed Ahmed Nur, the initiative also aims to help the authorities firm up on security and resolve housing ownership disputes.[57]

Air

During the post-independence period, Mogadishu International Airport offered flights to numerous global destinations.[96] In the mid-1960s, the airport was enlarged to accommodate more international carriers, with the state-owned Somali Airlines providing regular trips to all major cities.[97] By 1969, the airport's many landing grounds could also host small jets and DC 6B-type aircraft.[96]

The facility grew considerably in size in the post-independence period after successive renovation projects. With the outbreak of the civil war in the early 1990s, Mogadishu International Airport's flight services experienced routine disruptions and its grounds and equipment were largely destroyed. In the late 2000s, the K50 Airport, situated 50 kilometers to the south, served as the capital's main airport while Mogadishu International Airport, now renamed Aden Adde International Airport, briefly shut down.[98] However, in late 2010, the security situation in Mogadishu had significantly improved, with the federal government eventually managing to assume full control of the city by August 2011.[11]

In late 2010, SKA Air and Logistics, a Dubai-based aviation firm that specializes in conflict zones, was contracted by Somalia's Transitional Federal Government to manage operations over a period of ten years at the re-opened Aden Adde International Airport. With concurrent activities in Iraq and Afghanistan, among other complex areas, the company is expected to run security screening, passenger security and terminals. SKA staff have also begun re-training Somali airport personnel for the purpose. Although flights and other airport operations are presently limited to daylight hours, the firm is working on expanding activities once runway lighting and other features have been restored.[99]

As of 2012, the largest services using Aden Adde International Airport include the Somali-owned private carriers Jubba Airways and Daallo Airlines, in addition to UN charter planes, African Express Airways,[99] and Turkish Airlines.[100] The airport also offers flights to other Somali cities such as Galkayo, Berbera and Hargeisa, as well as international destinations like Djibouti, Jeddah,[101] and Istanbul.[100] In December 2011, the Turkish government unveiled plans to modernize the airport as part of Turkey's broader engagement in the local post-conflict reconstruction process. Among the scheduled renovations are new systems and infrastructure, including a modern control tower to monitor the airspace.[100] In July 2012, Mohammed Osman Ali (Dhagah-tur), the General Director of the Ministry of Aviation and Transport, also announced that the Somali government had begun preparations to revive the Mogadishu-based national carrier, Somali Airlines.[102] The first new aircraft were scheduled for delivery in December 2013.[103]

Sea

The Port of Mogadishu, also known as the Mogadishu International Port,[104] is the official seaport of Mogadishu. Classified as a major class port,[105] it is the largest harbour in the country.[106]

After incurring some damage during the civil war, the federal government launched the Mogadishu Port Rehabilitation Project,[104] an initiative to rebuild, develop and modernize the port.[106] The renovations included the installation of Alpha Logistics technology.[56] A joint international delegation consisting of the Director of the Port of Djibouti and Chinese officials specializing in infrastructure reconstruction concurrently visited the facility in June 2013. According to Mogadishu Port manager Abdullahi Ali Nur, the delegates along with local Somali officials received reports on the port's functions as part of the rebuilding project's planning stages.[106][107]

The Port of Mogadishu's management also reportedly reached an agreement with representatives of the Iranian company Simatech Shipping LLC to handle vital operations at the seaport. Under the name Mogadishu Port Container Terminal, the firm is slated to handle all of the port's technical and operational functions.[106]

Railway

There were projects during the 1980s to reactivate the 114 km railway between Mogadishu and Jowhar, built by the Italians in 1926 but dismantled in World War II by British troops. The Mogadishu-Villabruzzi Railway was planned in 1939 to reach Addis Ababa.

Media

Mogadishu has historically served as a media hub. In 1975, the Somali Film Agency (SFA), the nation's film regulatory body, was established in Mogadishu.[108] The SFA also organized the annual Mogadishu Pan-African and Arab Film Symposium (Mogpaafis), which brought together an array of prominent filmmakers and movie experts from across the globe, including other parts of Northeast Africa and the Arab world, as well as Asia and Europe.

In addition, there are a number of radio news agencies based in Mogadishu. Radio Mogadishu is the federal government-run public broadcaster. Established in 1951 in Italian Somaliland, it initially aired news items in both Somali and Italian.[109] The station was modernized with Russian assistance following independence in 1960, and began offering home service in Somali, Amharic and Oromo.[110] After closing down operations in the early 1990s due to the civil war, the broadcaster was officially re-opened in the early 2000s by the Transitional National Government.[111] Other radio stations headquartered in the city include Mustaqbal Radio, Radio Shabelle, Radio Bar-Kulan, Radio Kulmiye, Radio Dannan, Radio Dalsan, Radio Banadir, Radio Maanta, Gool FM, Radio Xurmo, and Radio Xamar, also known as Voice of Democracy.[112]

The Mogadishu-based Somali National Television (SNTV) is the central government-owned broadcaster. On 4 April 2011, the Ministry of Information of the Transitional Federal Government officially re-launched the station as part of an initiative to develop the national telecommunications sector.[113] SNTV broadcasts 24 hours a day, and can be viewed both within Somalia and abroad via terrestrial and satellite platforms.[114]

Somali popular music enjoys a large audience in Mogadishu, and was widely sold prior to the civil war.[115] With the government managing to secure the city in mid-2011, radios once again play music. On 19 March 2012, an open concert was held in the city, which was broadcast live on local television.[48] In April 2013, the Waayaha Cusub ensemble also organized the Reconciliation Music Festival, the first international music festival to be held in Mogadishu in two decades.[116][117]

Notable Mogadishans

- Ali Mohammed Ghedi, former Prime Minister of Somalia

- Ayub Daud, professional footballer

- Barkhad Abdi, actor, film director and producer

- Cristina Ali Farah, author and intellectual

- Diriye Osman, writer and visual artist

- Fatima Siad, fashion model

- Hassan Abshir Farah, MP and former Prime Minister of Somalia and Mayor of Mogadishu

- Hawa Abdi, physician and social activist

- Iman, supermodel

- K'naan, award-winning musician

- Luciano Ceri, singer-songwriter, journalist and radio host.

- Mo Farah, international track and field athlete

- Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, former Prime Minister of Somalia

- Mohamed Malimey, football coach

- Mohamed Nur, Mayor of Mogadishu

- Mustafa Mohamed, professional athlete

- Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke, former Prime Minister of Somalia

- Rageh Omaar, award-winning journalist

- Sa'id of Mogadishu, 14th century Islamic scholar and traveler

- Saba Anglana, international singer and actress

- Shaykh Sufi, 19th-century scholar, poet, reformist and astrologist

- Yasmin Warsame, supermodel

- Zahra Bani, professional athlete

Sister city

| Country | City |

|---|---|

| |

|

| |

|

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 1991, p. 829.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Somalia entry at The World Factbook

- ↑ Dictionary Reference: Mogadishu: /ˌmɔːɡəˈdiːʃuː/

- ↑ The Free Dictionary: Mogadishu: /ˌmoʊɡəˈdiːʃuː/, /-ˈdɪʃuː/, /ˌmɔː-/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Oliver & Fage 1960, p. 216.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Royal Anthropological Institute 1953, p. 50–51.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Lewis 1998, p. 47.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Lewis 1965, p. 37.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lewis 1988, p. 38.

- ↑ Venter 1975, p. 152.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Independent Newspapers Online (2011-08-10). "Al-Shabaab ‘dug in like rats’". Iol.co.za.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mulupi, Dinfin. "Mogadishu: East Africa’s newest business destination?". Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ Laitin & Samatar 1987, p. 12.

- ↑ Fage & Oliver 1986, p. 30.

- ↑ Lewis 1988, p. 20.

- ↑ Subrahmanyam 1998, p. 121.

- ↑ Oliver 1977, p. 190.

- ↑ Huntingford 1980, p. 83.

- ↑ Metz & Library of Congress. Federal Research Division 1993, p. n.i..

- ↑ Shinnie 1971, p. 135.

- ↑ Versteegh 2008, p. 276.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Laitin & Samatar 1987, p. 15.

- ↑ Kusimba 1999, p. 58.

- ↑ Bevilacqua, Clementi & Franzina 2001, p. 233.

- ↑ Termentin, Fernando (13 May 2005). "Somalia, una nazione che non esiste" (in Italian). Pagine di Difesa. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ "Il Razionalismo nelle colonie italiane 1928-1943 - La «nuova architettura» delle Terre d’Oltremare". Fedoa. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica 2002, p. 835.

- ↑ Greystone 1967, p. 338.

- ↑ Sachs 1988, p. 290.

- ↑ Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Richard Ford (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 1-56902-073-6.

- ↑ Fage, Oliver & Crowder 1984, p. 478.

- ↑ Americana Corporation 1976, p. 214.

- ↑ Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Coup d'Etat", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, retrieved 21 October 2009.

- ↑ Wiles 1982, p. 279.

- ↑ Frankel 1992, p. 306.

- ↑ ARR 1978, p. 602.

- ↑ Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part I". WardheerNews. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- ↑ New People Media Centre 2005, p. 94–105.

- ↑ Fitzgerald 2002, p. 25.

- ↑ Library Information and Research Service, The Middle East: Abstracts and index, Volume 2, (Library Information and Research Service: 1999), p.327.

- ↑ Ken Rutherford, Humanitarianism Under Fire: The US and UN Intervention in Somalia, Kumarian Press, July 2008, ISBN 1-56549-260-9

- ↑ "Ethiopian Invasion of Somalia". Globalpolicy.org. 2007-08-14. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ PNT The Gazette Edition (2011-01-12). "Somalia President, Parliament Speaker dispute over TFG term". Garoweonline.com. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2009-05-01). "USCIRF Annual Report 2009 – The Commission's Watch List: Somalia". Unhcr.org. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ "Somalia". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 2009-05-14. Retrieved 31 May 2009.

- ↑ African Press Agency (22 May 2010). "UN boss urges support for Somalia ahead of Istanbul summit". Horseed Media. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ "Security Council Meeting on Somalia". Somaliweyn.org.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Guled, Abdi (3 April 2012). "Sports, arts and streetlights: Semblance of normal life returns to Mogadishu, despite mortars Read it on Global News: Global News | Sports, arts and streetlights: Semblance of normal life returns to Mogadishu, despite mortars". Associated Press. Retrieved 26 June 2012.

- ↑ "Districts of Somalia". Statoids.com. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Ali, Laila (11 January 2013). "'Mogadishu is like Manhattan': Somalis return home to accelerate progress". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "Wetter im Detail: Klimadaten". BBC Weather. Retrieved 11 April 2012.

- ↑ "Monthly - Weather Averages Summary". http://www.weatherbase.com/.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Somalia: UN Envoy Says Inauguration of New Parliament in Somalia 'Historic Moment'". Forum on China-Africa Cooperation. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ↑ "Guidebook to the Somali Draft Provisional Constitution". Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- ↑ Freeman, Colin (15 May 2011). "How a modest council worker from Camden came to be the Mayor of Mogadishu". Telegraph. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 56.6 56.7 "Number of Infrastructure Development Projects are underway in Mogadishu". Act For Somalia. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 "Banadir officials launch Mogadishu Street Naming Project". Bar-Kulan. 29 January 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Embassies in Mogadishu". Aden Adde International Airport. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ The Earth and its Inhabitants: Africa (South and East Africa)”, authored by Elisee Reclus and published by the D. Appleton and Company. 1889

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "War-torn Somalia stages TEDx conference". Phys.org. 17 May 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Turkish organisations open construction yard in Mogadishu". Sabahi. 14 November 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ "Somali capital hosts entrepreneur talks". AFP. 31 August 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ Somalia business keen to join forces for peace

- ↑ Newly-found Somali company to bring peace to country

- ↑ Abbink 1999, p. 18.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 "Bantu ethnic identities in Somalia" (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Rutter 2003, p. 264.

- ↑ "http://somalilandpress.com/somalia-returning-diaspora-help-rebuild-31144". Somalilandpress.

- ↑ AARP 1975, p. 10.

- ↑ Garlake 1966, p. 10.

- ↑ Tebaldi, Giovanni (2001). Consolata Missionaries in the World (1901-2001). Paulines Publications Africa. p. 127. ISBN 9966210237.

- ↑ "AFRICA/SOMALIA - "I found signs of hope," said Bishop Bertin who has just returned from Mogadishu". Agenzia Fides. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ Reports Service: Northeast Africa series, Volume 13, Issue 1. American Universities Field Staff. 1966.

- ↑ Crespo-Toral, H. (1988). "Museum development and monuments conservation: Somalia". UNESCO. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Lengyel, Oguz Janos (1982). "National Museum of Somalia, Mogadiscio: Roof Restoration Project". UNESCO. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ "Mogadishu Points of interest". Aden Adde International Airport. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Development of services: National Library". UNESCO. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Shephard, Michelle (19 July 2013). "Somalia's national library rises amid the ruins". Toronto Star. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia to rebuild national library". Waamood. 22 December 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia's National Theatre: Still defiant". The Economist. 21 September 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 "Somalia: Gov't, China Officially Sign Cooperation Agreement". Dalsan Radio. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ "London conference aims to speed Somalia recovery". AFP. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Warehouse for Rent in Bakaara Market". Tabaarak. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 "Somalia is ‘ripe for investment’, says Mogadishu hotel owner". How We Made It In Africa. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Mogadishu Hotels". Aden Adde International Airport. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Cabinet endorses plans to reopen Somali National University". Horseed Media. 14 November 2013. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ "EDU Accreditation". Mogadishu University.

- ↑ Mohamed, Mahmoud (17 August 2012). "Profiles of Somalia's top presidential candidates". Sabahi. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ↑ "SIMAD University - History". SIMAD University. Retrieved 21 November 2013.

- ↑ Daily report: People's Republic of China, Issues 53-61, (National Technical Information Service: 1986)

- ↑ "Mogadishu looks to future, renovates sports stadiums". Sabahi. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ "Somalia". World Taekwondo Federation. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ↑ Jibril, Dahir (3 October 2013). "Mogadishu roads get much needed upgrades". Sabahi. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ Adam, Ali (20 February 2013). "Mogadishu Municipality resumes solar light installations on major roads". Sabahi. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ Jibril, Dahir (14 June 2013). "New taxi companies offer peace of mind to Mogadishu residents". Sabahi. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Europa Publications (1969). The Middle East. Europa Publications. p. 614.

- ↑ Instituto di Zoologia 1966, p. 342.

- ↑ Schmitz, Sebastain (2007). "By Ilyushin 18 to Mogadishu". Airways 14 (7): 12–17. ISSN 1074-4320.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 "SKA will run airport operations in Mogadishu". News.cheapflighthouse.co.uk. 2011-01-01. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 Khalif, Abdulkadir (16 February 2012). "Turkish carrier to start direct Mogadishu flights in March". Africa Review.

- ↑ McGinley, Shane (29 December 2010). "Dubai’s SKA signs deal to manage Mogadishu airport". Arabian Business Publishing Ltd.

- ↑ "Somalia to revive national airline after 21 years". Laanta. 24 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ "The long awaited Somali Airlines is Coming Back!". Keydmedia Online. 20 November 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 "The Official Website of the Mogadishu International Port". Mogadishu Port. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ "Istanbul conference on Somalia 21 – 23 May 2010 - Draft discussion paper for Round Table "Transport infrastructure"". Government of Somalia. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 106.3 Khalif, Abdulkadir (12 June 2013). "Djibouti and China to rebuild Mogadishu port". Africa Review. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ "Chinese-Djiboutian delegation visits Mogadishu port to plan reconstruction". Sabahi. 13 June 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Bakr, Labib & Kandil 1985, p. 25.

- ↑ World radio TV handbook, (Billboard Publications., 1955), p.77.

- ↑ Blair 1965, p. 126.

- ↑ "SOMALIA: TNG launches “Radio Mogadishu”". IRIN. 24 August 2001. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Mustaqbal Radio, Bar-Kulan, Radio Kulmiye, Radio Dannan,Radio Dalsan, Radio Banadir,Radio Maanta, Gool FM, Radio Xurmo and Radio Xamar

- ↑ "After 20 years, Somali president inaugurates national TV station". AHN. 4 April 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

- ↑ Somalia launches national TV

- ↑ "Somalia: Musicians undaunted with music ban". Africanews.com. 2010-06-21. Retrieved 25 May 2012.

- ↑ "Mogadishu music festival helps city move past sounds of war". Fédération internationale des coalitions pour la diversité culturelle. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ "Somali Webchat Series". IIP CO.NX. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- Bibliography

- AARP (1975). Art and Archaeology Research Papers. AARP.

- Abbink, Jan (1999). The Total Somali Clan Genealogy: A Preliminary Sketch. African Studies Centre.

- Americana Corporation (1976). The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac. Americana Corporation. ISBN 978-0-7172-0106-8.

- ARR (1978). Arab Report and Record. Economic Features, Ltd.

- Bakr, Yahya Abu; Labib, Saʻad; Kandil, Hamdy (1985). Development of communication in the Arab states: needs and priorities. Unesco. ISBN 978-92-3-102082-7.

- Bevilacqua, Piero; Clementi, Andreina De; Franzina, Emilio (2001). Storia dell'emigrazione italiana (in Italian). Donzelli Editore. ISBN 978-88-7989-655-9.

- Blair, Thomas Lucien Vincent (1965). Africa: a market profile. Praeger.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. (1991). The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Marcopædia. Encyclopædia Britannica. ISBN 978-0-85229-529-8.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (2002). Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. ISBN 978-0-85229-787-2.

- Fage, John Donnelly; Oliver, Roland Anthony; Crowder, Michael (1984). The Cambridge history of Africa. From 1905 to 1940 8. Cambridge University Press.

- Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1986). The Cambridge History of Africa 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22505-2.

- Fitzgerald, Nina J. (2002). Somalia: Issues, History, and Bibliography. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-265-8.

- Frankel, Benjamin (1 October 1992). The Cold War, 1945-1991. Gale Research International, Limited. ISBN 978-0-8103-8926-7.

- Garlake, Peter S. (1966). The Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast. Institute. p. 10.

- Greystone (1967). The World and Its Peoples: Africa, North and East. Greystone Press.

- Huntingford, George Wynn Brereton (1980). The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-904180-05-3.

- Instituto di Zoologia (1966). Italian Journal of Zoology. Università di Firenze.

- Kusimba, Chapurukha Makokha (1 January 1999). The Rise and Fall of Swahili States. AltaMira Press. ISBN 978-0-7619-9051-2.

- Laitin, David D.; Samatar, Said S. (1987). Somalia: nation in search of a state. Westview Press.

- Lewis, I. M. (1965). The Modern History of Somaliland: From Nation to State. F.A. Praeger.

- Lewis, I. M. (1988). A Modern History of Somalia: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-7402-4.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 August 1998). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-1-56902-104-0.

- Metz, Helen Chapin; Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). Somalia: a country study. Thomas Leiper Kane Collection. Federal Research Division. ISBN 978-0-8444-0775-3.

- New People Media Centre (2005). New People. Nairobi, Kenya: New People Media Centre, Comboni Missionaries.

- Oliver, Roland Anthony; Fage, John Donnelly (1960). The Journal of African History 1. Cambridge University Press.

- Oliver, Roland Anthony (1977). The Cambridge History of Africa: From c. 1050 to c. 1600 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22215-0.

- Royal Anthropological Institute (1953). Man 53. Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland.

- Rutter, Jill (2003). Supporting Refugee Children in 21st Century Britain: A Compendium of Essential Information. Trentham Books. ISBN 978-1-85856-292-6.

- Sachs, Moshe Y. (1988). Worldmark encyclopedia of the nations. Worldmark Press. ISBN 978-0-471-62406-6.

- Shinnie, P.L. (1971). The African Iron Age.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (29 October 1998). The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64629-1.

- Venter, Al J. (1975). Africa Today. Macmillan South Africa. ISBN 978-0-86954-023-7.

- Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-14476-7.

- Wiles, Peter John de la Fosse (1982). The New Communist Third World: An Essay in Political Economy. Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-2709-9.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mogadishu. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mogadishu. |

- Benadir Regional Administration - Transitional Federal Government of Somalia

- Mogadishu at Google Maps

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mukdishu". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Mukdishu". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||