Milnor number

In mathematics, and particularly singularity theory, the Milnor number, named after John Milnor, is an invariant of a function germ.

If f is a complex-valued holomorphic function germ then the Milnor number of f, denoted μ(f), is either an integer greater than or equal to zero, or it is infinite. It can be considered both a geometric invariant and an algebraic invariant. This is why it plays an important role in algebraic geometry and singularity theory.

Geometric interpretation

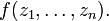

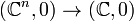

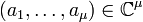

Consider a holomorphic complex function germ f:

Thus for an n-tuple of complex numbers  we get a complex number

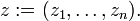

we get a complex number  We shall write

We shall write

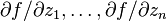

We say that f is singular at a point  if the first order partial derivatives

if the first order partial derivatives  are all zero at

are all zero at  . As the name might suggest: we say that a singular point

. As the name might suggest: we say that a singular point  is isolated if there exists a sufficiently small neighbourhood

is isolated if there exists a sufficiently small neighbourhood  of

of  such that

such that  is the only singular point in U. We say that a point is a degenerate singular point, or that f has a degenerate singularity, at

is the only singular point in U. We say that a point is a degenerate singular point, or that f has a degenerate singularity, at  if

if  is a singular point and the Hessian matrix of all second order partial derivatives has zero determinant at

is a singular point and the Hessian matrix of all second order partial derivatives has zero determinant at  :

:

We assume that f has a degenerate singularity at 0. We can speak about the multiplicity of this degenerate singularity by thinking about how many points are infinitesimally glued. If we now perturb the image of f in a certain stable way the isolated degenerate singularity at 0 will split up into other isolated singularities which are non-degenerate! The number of such isolated non-degenerate singularities will be the number of points that have been infinitesimally glued.

Precisely, we take another function germ g which is non-singular at the origin and consider the new function germ h := f + εg where ε is very small. When ε = 0 then h = f. The function h is called the morsification of f. It is very difficult to compute the singularities of h, and indeed it may be computationally impossible. This number of points that have been infinitesimally glued, this local multiplicity of f, is exactly the Milnor number of f.

Algebraic interpretation

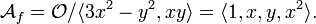

Using some algebraic techniques we can calculate the Milnor number of f effortlessly. By  denote the ring of function germs

denote the ring of function germs  . By

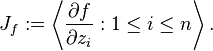

. By  denote the Jacobian ideal of f:

denote the Jacobian ideal of f:

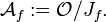

The local algebra of f is then given by the quotient algebra

Notice that this quotient space will actually be a vector space, although it may not be finite dimensional. The Milnor number is then equal to the complex dimension of the local algebra:

It follows from Hilbert's Nullstellensatz that  is finite if and only if the origin is an isolated critical point of f; that is, there is a neighbourhood of 0 in

is finite if and only if the origin is an isolated critical point of f; that is, there is a neighbourhood of 0 in  such that the only critical point of f inside that neighbourhood is at 0.

such that the only critical point of f inside that neighbourhood is at 0.

Examples

Here we give some worked examples in two variables. Working with only one is too simple and does not give a feel for the techniques, whereas working with three variables can be quite tricky. Two is a nice number. Also we stick to polynomials. If f is only holomorphic and not a polynomial, then we could have worked with the power series expansion of f.

1

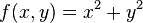

Consider a function germ with a non-degenerate singularity at 0, say  . The Jacobian ideal is just

. The Jacobian ideal is just  . We next compute the local algebra:

. We next compute the local algebra:

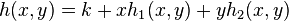

To see why this is true we can use Hadamard's lemma which says that we can write any function  as

as

for some constant k and functions  and

and  in

in  (where either

(where either  or

or  or both may be exactly zero). So, modulo functional multiples of x and y, we can write h as a constant. The space of constant functions is spanned by 1, hence

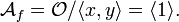

or both may be exactly zero). So, modulo functional multiples of x and y, we can write h as a constant. The space of constant functions is spanned by 1, hence

It follows that μ(f) = 1. It is easy to check that for any function germ g with a non-degenerate singularity at 0 we get μ(g) = 1.

Note that applying this method to a non-singular function germ g we get μ(g) = 0.

2

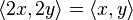

Let  , then

, then

So in this case  .

.

3

One can show that if  then

then

This can be explained by the fact that f is singular at every point of the x-axis.

Versal Deformations

Let f have finite Milnor number μ, and let  be a basis for the local algebra, considered as a vector space. Then a miniversal deformation of f is given by

be a basis for the local algebra, considered as a vector space. Then a miniversal deformation of f is given by

where  .

These deformations (or unfoldings) are of great interest in much of science.

.

These deformations (or unfoldings) are of great interest in much of science.

Invariance

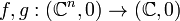

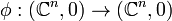

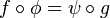

We can collect function germs together to construct equivalence classes. One standard equivalence is A-equivalence. We say that two function germs  are A-equivalent if there exist diffeomorphism germs

are A-equivalent if there exist diffeomorphism germs  and

and  such that

such that  : there exists a diffeomorphic change of variable in both domain and range which takes f to g.

: there exists a diffeomorphic change of variable in both domain and range which takes f to g.

The Milnor number does not offer a complete invariant for function germs. We do have that if f and g are A-equivalent then μ(f) = μ(g).

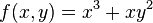

The converse is false: there exist function germs f and g with μ(f) = μ(g) which are not A-equivalent. To see this consider  and

and  . We have

. We have  but f and g are clearly not A-equivalent since the Hessian matrix of f is equal to zero while that of g is not (and the rank of the Hessian is an A-invariant, as is easy to see).

but f and g are clearly not A-equivalent since the Hessian matrix of f is equal to zero while that of g is not (and the rank of the Hessian is an A-invariant, as is easy to see).

References

- Arnold, V.I.; Gussein-Zade, S.M.; Varchenko, A.N. (1985). Singularities of differentiable maps. Volume 1. Birkhauser.

- Gibson, Christopher G. (1979). Singular Points of Smooth Mappings. Research Notes in Mathematics. Pitman.

- Milnor, John (1963). Morse Theory. Annals of Mathematics Studies. Princeton University Press.

- Milnor, John (1969). Singular points of Complex Hypersurfaces. Annals of Mathematics Studies. Princeton University Press.