Mikveh

| Part of a series on |

| Judaism |

|---|

|

|

Religious roles |

|

Ritual objects |

|

Relations with other religions |

|

Related topics |

|

|

| Repentance in Judaism Teshuva "Return" |

|---|

|

Repentance, atonement and higher ascent in Judaism |

| In the Hebrew Bible |

|

|

Altars · Korban Temple in Jerusalem Prophecy within the Temple |

| Aspects |

|

Confession · Atonement Love of God · Awe of God Mystical approach Ethical approach Meditation · Services Torah study Tzedakah · Mitzvot |

| In the Jewish calendar |

|

Month of Elul · Selichot Rosh Hashanah Shofar · Tashlikh Ten Days of Repentance Kapparot · Mikveh Yom Kippur Sukkot · Simchat Torah Ta'anit · Tisha B'Av Passover · The Omer Shavuot |

| In contemporary Judaism |

|

Baal Teshuva movement Jewish Renewal |

Mikveh (sometimes spelled mikvah, mikve, or mikva) (Hebrew: מִקְוֶה / מקווה, Modern Mikve Tiberian Miqwā; plural: mikva'ot or mikves (Yiddish)[1][2] Hebrew: מִקְוֶוֹת / מִקְוָאות) is a bath used for the purpose of ritual immersion in Judaism. The word "mikveh", as used in the Hebrew Bible, literally means a "collection" – generally, a collection of water.[3]

Several biblical regulations specify that full immersion in water is required to regain ritual purity after ritually impure incidents have occurred. A person was required to be ritually pure in order to enter the Temple. In addition, a convert to Judaism is required to immerse in a mikveh as part of the his/her conversion, and a woman is required to immerse in a mikveh after her menstrual period or childbirth before she and her husband can resume marital relations. In this context, "purity" and "impurity" are imperfect translations of the Hebrew "tahara" and "tumah", respectively, in that the negative connotation of the word impurity is not intended; rather being "impure" is indicative of being in a state in which certain things are prohibited (as relevant) until one has become "pure" again by immersion in a mikveh.

Full ritual purity of the type needed to enter or serve in the Temple is not attainable by anyone today as we are all considered to be ritually impure by virtue of exposure to death (via exposure to corpses or to graves and cemeteries etc.) and that kind of ritual purity can only be obtained when the Jewish people have a Red heifer.

Most forms of impurity can be nullified through immersion in any natural collection of water. However, some impurities, such as a zav, require "living water,"[4] such as springs or groundwater wells. Living water has the further advantage of being able to purify even while flowing, as opposed to rainwater which must be stationary in order to purify. The mikveh is designed to simplify this requirement, by providing a bathing facility that remains in ritual contact with a natural source of water.

Its main uses nowadays are:

- by Jewish women to achieve ritual purity after menstruation or childbirth;

- by Jewish men to achieve ritual purity (see details below);

- as part of a traditional procedure for conversion to Judaism;

- to immerse newly acquired utensils used in serving and eating food.

In Orthodox Judaism, these regulations are steadfastly adhered to, and consequently the mikveh is central to an Orthodox Jewish community, and they formally hold in Conservative Judaism as well. The existence of a mikveh is considered so important in Orthodox Judaism, that an Orthodox community is required to construct a mikveh before building a synagogue, and must go to the extreme of selling Torah scrolls or even a synagogue if necessary, to provide funding for the construction.[5] Reform Judaism and Reconstructionist Judaism regard the biblical regulations as anachronistic to some degree, and consequently do not put much importance on the existence of a mikveh. Some opinions within Conservative Judaism have sought to retain the ritual requirements of a mikveh while recharacterizing the theological basis of the ritual in concepts other than ritual purity.

Ancient mikvehs dating from before the late first century can be found throughout the land of Israel as well as in historic communities of the Jewish diaspora. In modern times, mikvehs can be found in most communities in Orthodox Judaism. Jewish funeral homes may have a mikveh for immersing a body during the purification procedure (tahara) before burial.

Requirements of a mikveh

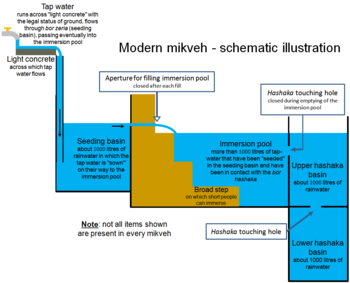

The traditional rules regarding the construction of a mikveh are based on those specified in classical rabbinical literature. According to these rules, a mikveh must be connected to a natural spring or well of naturally occurring water, and thus can be supplied by rivers and lakes which have natural springs as their source.[6] A cistern filled by the rain is also permitted to act as a mikveh's water supply. Similarly snow, ice and hail are allowed to act as the supply of water to a mikveh, as long as it melts in a certain manner.[7] A river that dries up on a regular basis cannot be used because it is presumed to be mainly rainwater, which cannot purify while flowing. Oceans for the most part have the status of natural springs.

A mikveh must, according to the classical regulations, contain enough water to cover the entire body of an average-sized person; based on a mikveh with the dimensions of 3 cubits long, 1 cubit wide, and 1 cubit deep, the necessary volume of water was estimated as being 40 seah of water.[8][9] The exact volume referred to by a seah is debated, and classical rabbinical literature specifies only that it is enough to fit 144 eggs;[10] most Orthodox Jews use the stringent ruling of the Avrohom Yeshaya Karelitz, according to which one seah is 14.3 litres, and therefore a mikveh must contain approximately 575 litres.[11] This volume of water could be topped up with water from any source,[12] but if there were less than 40 seahs of water in the mikveh, then the addition of 3 or more pints of water from an unnatural source would render the mikveh unfit for use, regardless of whether water from a natural source was then added to make up 40 seahs from a natural source;[3] a mikveh rendered unfit for use in this way would need to be completely drained away and refilled from scratch.[3]

There are also classical requirements for the manner in which the water can be stored and transported to the pool; the water must flow naturally to the mikveh from the source, which essentially means that it must be supplied by gravity or a natural pressure gradient, and the water cannot be pumped there by hand or carried. It was also forbidden for the water to pass through any vessel which could hold water within it (however pipes open to the air at both ends are fine)[13] As a result, tap water could not be used as the primary water source for a mikveh, although it can be used to top the water up to a suitable level.[12] To avoid issues with these rules in large cities, various methods are employed to establish a valid mikveh. One is that tap water is made to flow over the top of a kosher mikveh, and through a conduit into a larger pool. A second method is to create a mikveh in a deep pool, place a floor with holes over that and then fill the upper pool with tap water. In this way, the person dipping is actually "in" the pool of rain water.

Most contemporary mikvehs are indoor constructions, involving rain water collected from a cistern, and passed through a duct by gravity into an ordinary bathing pool; the mikveh can be heated, taking into account certain rules, often resulting in an environment not unlike a spa.

Reasons for immersion in a Mikveh

Historic reasons

Traditionally, the mikveh was used by both men and women to regain ritual purity after various events, according to regulations laid down in the Torah and in classical rabbinical literature.

The Torah requires full immersion

- after Keri[14] — normal emissions of semen, whether from sexual activity, or from nocturnal emission bathing in a mikveh due to Keri is known as tevilath Ezra ("the immersion of Ezra")

- after Zav/Zavah[15] — abnormal discharges of body fluids

- after Tzaraath[16] — certain skin condition(s). These are termed lepra in the Septuagint, and therefore traditionally translated into English as leprosy; this is probably a translation error, as the Greek term lepra mostly refers to psoriasis, and the Greek term for leprosy was elephas/elephantiasis.

- by anyone who came into contact with someone suffering from Zav/Zavah, or into contact with someone still in Niddah (normal menstruation), or who comes into contact with articles that have been used or sat upon by such persons[17][18]

- by Jewish priests when they are being consecrated[19]

- by the Jewish high priest on Yom Kippur, after sending away the goat to Azazel, and by the man who leads away the goat[20]

- by the Jewish priest who performed the Red Heifer ritual[21]

- after contact with a corpse or grave,[22] in addition to having the ashes of the Red heifer ritual sprinkled upon them

- after eating meat from an animal that died naturally[23]

Classical rabbinical writers conflated the rules for zavah and niddah. It also became customary for priests to fully immerse themselves before Jewish holidays, and the laity of many communities subsequently adopted this practice. Converts to Judaism are required to undergo full immersion in water.

Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan in Waters of Eden[24] connects the laws of impurity to the narrative in the beginning of Genesis. According to Genesis, by eating of the fruit, Adam and Eve had brought death into the world. Kaplan points out that most of the laws of impurity relate to some form of death (or in the case of Niddah the loss of a potential life). One who comes into contact with one of the forms of death must then immerse in water which is described in Genesis as flowing out of the Garden of Eden (the source of life) in order to cleanse oneself of this contact with death (and by extension of sin).

In Modern Judaism

Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism generally adheres to the classical regulations and traditions, and consequently Orthodox Jewish women are obligated to immerse in a mikveh between Niddah and sexual relations with their husbands. This includes brides before their marriage, and married women after their menstruation period or childbirth. In accordance with Orthodox rules concerning modesty, men and women are required to immerse in separate mikveh facilities in separate locations, or to use the mikveh at different designated times.

Converts to Orthodox Judaism, regardless of gender, are also required to immerse in a mikveh. It is customary for Orthodox Jews to immerse before Yom Kippur,[25] and married women sometimes do so as well. In the customs of certain Jewish communities, men also use a mikveh before Jewish holidays;[25] the men in certain communities, especially hasidic and haredi groups, also practice immersion before each Shabbat, and some immerse in a mikveh every single day. Although the Temple Mount is treated by many Orthodox Jewish authorities as being forbidden territory, a small number of groups permit access, but require immersion before ascending the Mount as a precaution.

Orthodox Judaism requires that vessels and utensils must be immersed in a mikveh before being used for food, if they had been purchased from a non-Jew.

Obligatory immersion in Orthodox Judaism

Immersion in a mikveh is obligatory in contemporary Orthodox Jewish practice in the following circumstances:

- Women

- Following the niddah period after menstruation, prior to resuming marital relations

- Following the niddah period after childbirth, prior to resuming marital relations

- By a bride, before her wedding

- Either gender.

- As part of a conversion to Judaism

- Immersion of utensils acquired from a gentile

Customary immersion in Orthodox Judaism

Immersion in a mikveh is customary in contemporary Orthodox Jewish practice in the following circumstances:

- Men

- By a bridegroom, on the day of his wedding, according to the custom of some communities

- By a father, prior to the circumcision of his son, according to the custom of some communities.

- By a kohen prior to a service in which he will recite the priestly blessing, according to the custom of some communities

- Before Yom Kippur, according to the custom of some communities

- Before a Jewish holiday, according to the custom of some communities

- Weekly before Shabbat, under Hasidic and Haredi customs

- Every day, under Hasidic customs

Immersion for men is more common in Hasidic communities, and non-existent in others, like German Jewish communities.

Conservative Judaism

In a series of responsa on the subject of Niddah in December 2006, the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards of Conservative Judaism reaffirmed a requirement that Conservative women use a mikveh monthly following the end of the niddah period following menstruation, while adapting certain leniencies including reducing the length of the period. The three responsa adapted permit a range of approaches from an opinion reaffirming the traditional ritual to an opinion declaring the concept of ritual purity does not apply outside the Temple in Jerusalem, proposing a new theological basis for the ritual, adapting new terminology including renaming the observances related to menstruation from taharat hamishpacha family purity to kedushat hamishpaha [family holiness] to reflect the view that the concept of ritual purity is no longer considered applicable, and adopting certain leniencies including reducing the length of the niddah period.[26][27][28][29]

Isaac Klein's A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice, a comprehensive guide frequently used within Conservative Judaism also addresses Conservative views on other uses of a mikveh, but because it predates the 2006 opinions it describes an approach more closely resembling the Orthodox one and does not address the leniencies and views those opinions reflected. Rabbi Miriam Berkowitz's recent book Taking the Plunge: A Practical and Spiritual Guide to the Mikveh (Jerusalem: Schechter Institute, 2007) offers a comprehensive discussion of contemporary issues and new mikveh uses along with traditional reasons for observance, details of how to prepare and what to expect, and how the laws developed. Conservative Judaism encourages but does not require immersion before Jewish Holidays (including Yom Kippur), nor the immersion of utensils purchased from non-Jews. New uses are being developed throughout the liberal world for healing (after rape, incest, divorce etc.) or celebration (milestone birthdays, anniversaries, ordination, or reading Torah for the first time).

As in Orthodox Judaism, converts to Judaism through the Conservative movement are required to immerse themselves in a mikveh. Two Jews must witness the event, at least one of which must actually see the immersion. Immersion into a mikveh has been described as a very emotional, life-changing experience similar to a graduation.[30]

Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism

Reform and Reconstructionist Judaism do not hold the halachic requirements of mikveh the way Orthodox Judaism does. However, there are growing trends toward using mikveh for conversions, wedding preparation, and even before holidays.[31] While most Reform Jews will probably never see the inside of a mikveh, there are many (particularly converts) who will fulfill the mitzvah at least once in their lives.[citation needed]

Requirements during use of a mikveh

_mikveh.jpg)

The classical requirement for full immersion was traditionally interpreted as requiring water to literally touch every part of the body, and for this reason all clothing, jewellery, and even bandages must be removed; in a contemporary mikveh used by women, there is usually an experienced attendant, commonly called the mikveh lady, to watch the immersion and ensure that the woman has been entirely covered in water.

According to rabbinical tradition, the hair counts as part of the body, and therefore water is required to touch all parts of it, thus meaning that braids cannot be worn during immersion; this has resulted in debate between the different ethnic groups within Judaism, about whether hair combing is necessary before immersion. The Ashkenazi community generally supports the view that hair must be combed straight so that there are no knots, but some Black Jews take issue with this stance, particularly when it comes to dreadlocks.[citation needed] A number of rabbinical rulings argue in support of dreadlocks, on the basis that

- dreadlocks can sometimes be loose enough to become thoroughly saturated with water, particularly if the person had first showered

- combing dreadlocked hair can be painful

- although a particularly cautious individual would consider a single knotted hair as an obstruction, in most cases hair is loose enough for water to pass through it, unless each hair is individually knotted[32]

Allegorical uses of the term Mikveh

The word mikveh makes use of the same root letters in Hebrew as the word for "hope" and this has served as the basis for homiletical comparison of the two concepts in both biblical and rabbinic literature. For instance, in the Book of Jeremiah, the word mikveh is used in the sense of "hope," but at the same time also associated with "living water":

- O Hashem, the Hope [mikveh] of Israel, all who forsake you will be ashamed ... because they have forsaken Hashem, the fountain of living water[33]

- Are there any of the worthless idols of the nations, that can cause rain? or can the heavens give showers? Is it not you, Hashem our God, and do we not hope [nekaveh] in you? For you have made all these things.[34]

In the Mishnah, following on from a discussion about Yom Kippur, immersion in a Mikveh is compared by Rabbi Akiva with the relationship between God and Israel. Akiva refers to the description of God in the Book of Jeremiah as the "Mikveh of Israel", and suggests that "just as a mikveh purifies the contaminated, so does the Holy One, blessed is he, purify Israel".[35]

A different allegory is used by many Jews adhering to a belief in resurrection as one of the Thirteen Principles of Faith. Since "living water" in a lifeless frozen state (as ice) is still likely to again become living water (after melting), it became customary in traditional Jewish bereavement rituals to read the seventh chapter of the Mikvaot tractate in the Mishnah, following a funeral; the Mikvaot tractate covers the laws of the mikveh, and the seventh chapter starts with a discussion of substances which can be used as valid water sources for a mikveh - snow, hail, frost, ice, salt, and pourable mud.

See also

- Conversion to Judaism

- Mikva'ot - section of the Mishnah discussing the laws pertaining to the building and maintenance of a mikveh.

- Niddah

- Ritual washing in Judaism

- Bath (unit)

- Baptism

Footnotes

- ↑ Sivan, Reuven; Edward A Levenston (1975). The New Bantam-Megiddo Hebrew & English dictionary. Toronto; New York: Bantam Books. ISBN 0-553-26387-0.

- ↑ Lauden, Edna (2006). Multi Dictionary. Tel Aviv: Ad Publications. p. 397. ISBN 965-390-003-X.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jewish Encyclopedia

- ↑ Leviticus 15:13

- ↑ Berlin, Meshib Dabar, 2:45

- ↑ Sifra on Leviticus 11:36

- ↑ Mikvaot 7:1.

- ↑ Eruvin 4b

- ↑ Yoma 31a

- ↑ Numbers Rabbah, 18:17

- ↑ about 3 Koku, about 116 qafiz, about 126 Imperial Gallons, about 143 Burmese tins, and about 150 U.S. liquid gallons

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Mikvaot 3.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch Yoreh Deah 201:36

- ↑ Leviticus 15:16

- ↑ Leviticus 15:13

- ↑ Leviticus 14:6-9

- ↑ Leviticus 15:5-10

- ↑ Leviticus 15:19-27

- ↑ Exodus 29:4, Exodus 40:12

- ↑ 16:24&verse=&src=! Leviticus 16:24, 16:26, 16:28

- ↑ Numbers 19:7-8

- ↑ Numbers 19:19

- ↑ Leviticus 17:15

- ↑ Waters of Eden by Rabbi Aryeh Kaplan. ISBN 978-1-879016-08-8.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chayim, 581:4 and 606:4

- ↑ Rabbi Miriam Berkowitz, Mikveh and the Sanctity of Family Relations, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, Rabbinical Assembly, December 6, 2006

- ↑ Rabbi Susan Grossman, MIKVEH AND THE SANCTITY OF BEING CREATED HUMAN, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, Rabbinical Assembly, December 6, 2006

- ↑ Rabbi Avram Reisner, OBSERVING NIDDAH IN OUR DAY: AN INQUIRY ON THE STATUS OF PURITY AND THE PROHIBITION OF SEXUAL ACTIVITY WITH A MENSTRUANT, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, Rabbinical Assembly, December 6, 2006

- ↑ Rabbi Miriam Berkowitz, RESHAPING THE LAWS OF FAMILY PURITY FOR THE MODERN WORLD, Committee on Jewish Law and Standards, Rabbinical Assembly, December 6, 2006

- ↑ Freudenheim, Susan. "Becoming Jewish: Tales from the Mikveh." Jewish Journal. 8 May 2013. 8 May 2013.

- ↑ "Sue Fishkoff, Reimagining the Mikveh, Reform Judaism Magazine, Fall 2008". Reformjudaismmag.org. Retrieved 2012-12-25.

- ↑ Kolel Menachem, Kitzur Dinei Taharah: A Digest of the Niddah Laws Following the Rulings of the Rebbes of Chabad (Brooklyn, New York: Kehot Publication Society, 2005).

- ↑ Jeremiah 17:13

- ↑ Jeremiah 14:22

- ↑ Yoma 85b

References

- Isaac Klein, A Guide to Jewish Religious Practice, JTS Press, New York, 1992

- Kolel Menachem, Kitzur Dinei Taharah: A Digest of the Niddah Laws Following the Rulings of the Rebbes of Chabad, Kehot Publication Society, Brooklyn, New York, 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mikvaot. |

- Global Mikvah Directory (Mikvah.org)

- The Mikvah, by Rivkah Slonim (Chabad.org)

- The Mikvah: A Spiritual Experience

- Pathways to the Sacred video clip with Anita Diamant

- Mikvahs / Mikveh: Immersion in the Bible

- Europe's Oldest Mikveh in Syracuse, Italy

- Purification Rituals in Mediaeval Judaism - Videos made by scientists of the German Research Foundation for DFG Science TV

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||