Micellar electrokinetic chromatography

Micellar electrokinetic chromatography (MEKC), is a chromatography technique, used in analytical chemistry. It is a modification of capillary electrophoresis (CE), where the samples are separated by differential partitioning between micelles (pseudo-stationary phase) and a surrounding aqueous buffer solution (mobile phase).[1]

The basic set-up and detection methods used for MEKC are the same as those used in CE. The difference is that the solution contains a surfactant at a concentration that is greater than the critical micelle concentration (CMC). Above this concentration, surfactant monomers are in equilibrium with micelles.

In most applications, MEKC is performed in open capillaries under alkaline conditions to generate a strong electroosmotic flow. Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) is the most commonly used surfactant in MEKC applications. The anionic character of the sulfate groups of SDS cause the surfactant and micelles to have electrophoretic mobility that is counter to the direction of the strong electroosmotic flow. As a result, the surfactant monomers and micelles migrate quite slowly, though their net movement is still toward the cathode.[2] During a MEKC separation, analytes distribute themselves between the hydrophobic interior of the micelle and hydrophilic buffer solution as shown in figure 1.

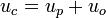

Analytes that are insoluble in the interior of micelles should migrate at the electroosmotic flow velocity,  , and be detected at the retention time of the buffer,

, and be detected at the retention time of the buffer,  . Analytes that solubilize completely within the micelles (analytes that are highly hydrophobic) should migrate at the micelle velocity,

. Analytes that solubilize completely within the micelles (analytes that are highly hydrophobic) should migrate at the micelle velocity,  , and elute at the final elution time,

, and elute at the final elution time,  .[3]

.[3]

Theory

The micelle velocity is defined by:

where  is the electrophoretic velocity of a micelle.[3]

is the electrophoretic velocity of a micelle.[3]

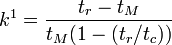

The retention time of a given sample should depend on the capacity factor,  :

:

where  is the total number of moles of solute in the micelle and

is the total number of moles of solute in the micelle and  is the total moles in the aqueous phase.[3] The retention time of a solute should then be within the range:

is the total moles in the aqueous phase.[3] The retention time of a solute should then be within the range:

Charged analytes have a more complex interaction in the capillary because they exhibit electrophoretic mobility, engage in electrostatic interactions with the micelle, and participate in hydrophobic partitioning.[4]

The fraction of the sample in the aqueous phase,  , is given by:

, is given by:

where  is the migration velocity of the solute.[3] The value

is the migration velocity of the solute.[3] The value  can also be expressed in terms of the capacity factor:

can also be expressed in terms of the capacity factor:

Using the relationship between velocity, tube length from the injection end to the detector cell ( ), and retention time,

), and retention time,  ,

,  and

and  , a relationship between the capacity factor and retention times can be formulated:[4]

, a relationship between the capacity factor and retention times can be formulated:[4]

The extra term enclosed in parenthesis accounts for the partial mobility of the hydrophobic phase in MEKC.[4] This equation resembles an expression derived for  in conventional packed bed chromatography:

in conventional packed bed chromatography:

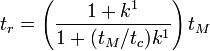

A rearrangement of the previous equation can be used to write an expression for the retention factor:[5]

From this equation it can be seen that all analytes that partition strongly into the micellar phase (where  is essentially ∞) migrate at the same time,

is essentially ∞) migrate at the same time,  . In conventional chromatography, separation of similar compounds can be improved by gradient elution. In MEKC, however, techniques must be used to extend the elution range to separate strongly retained analytes.[4]

. In conventional chromatography, separation of similar compounds can be improved by gradient elution. In MEKC, however, techniques must be used to extend the elution range to separate strongly retained analytes.[4]

Elution ranges can be extended by several techniques including the use of organic modifiers, cyclodextrins, and mixed micelle systems. Short-chain alcohols or acetonitrile can be used as organic modifiers that decrease  and

and  to improve the resolution of analytes that co-elute with the micellar phase. These agents, however, may alter the level of the EOF. Cyclodextrins are cyclic polysaccharides that form inclusion complexes that can cause competitive hydrophobic partitioning of the analyte. Since analyte-cyclodextrin complexes are neutral, they will migrate toward the cathode at a higher velocity than that of the negatively charged micelles. Mixed micelle systems, such as the one formed by combining SDS with the neutral surfactant Brij-35, can also be used to alter the selectivity of MEKC.[4]

to improve the resolution of analytes that co-elute with the micellar phase. These agents, however, may alter the level of the EOF. Cyclodextrins are cyclic polysaccharides that form inclusion complexes that can cause competitive hydrophobic partitioning of the analyte. Since analyte-cyclodextrin complexes are neutral, they will migrate toward the cathode at a higher velocity than that of the negatively charged micelles. Mixed micelle systems, such as the one formed by combining SDS with the neutral surfactant Brij-35, can also be used to alter the selectivity of MEKC.[4]

History

In 1984, the Terabe group reported a technique that enabled capillary electrophoresis (CE) instrumentation to be used in the separation of neutral (as well as ionic) species.

Applications of MEKC

The simplicity and efficiency of MEKC have made it an attractive technique for a variety of applications. Further improvements can be made to the selectivity of MEKC by adding chiral selectors or chiral surfactants to the system. Unfortunately, this technique is not suitable for protein analysis because proteins are generally too large to partition into a surfactant micelle and tend to bind to surfactant monomers to form SDS-protein complexes.[6]

Recent applications of MEKC include the analysis of uncharged pesticides,[7] essential and branched-chain amino acids in nutraceutical products,[8] hydrocarbon and alcohol contents of the marjoram herb.[9]

MEKC has also been targeted for its potential to be used in combinatorial chemical analysis. The advent of combinatorial chemistry has enabled medicinal chemists to synthesize and identify large numbers of potential drugs in relatively short periods of time. Small sample and solvent requirements and the high resolving power of MEKC have enabled this technique to be used to quickly analyze a large number of compounds with good resolution.

Traditional methods of analysis, like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), can be used to identify the purity of a combinatorial library, but assays need to be rapid with good resolution for all components to provide useful information for the chemist.[10] The introduction of surfactant to traditional capillary electrophoresis instrumentation has dramatically expanded the scope of analytes that can be separated by capillary electrophoresis.

References

- ↑ Terabe, S.; Otsuka, K.; Ichikawa, K.; Tsuchiya, A.; Ando, T. Anal. Chem. 1984, 56, 111.

- ↑ Baker, D.R. “Capillary Electrophoresis” John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, 1995.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Terabe, S.; Otsuka, K.; Ichikawa, K.; Tsuchiya, A.; Ando, T. Anal. Chem. 1984, 56, 113.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Cunico,R.L.; Goodin, K.M.; Wehr,T. “Basic HPLC and CE of Biomolecules” Bay Bioanalytical Laboratory: Richmond, CA, 1998.

- ↑ Foley, J.P. Anal. Chem. 1990, 62, 1302.

- ↑ Skoog, D.A.; Holler, F.J.; Nieman, T.A. “Principles of Instrumental Analysis, 5th ed.” Saunders college Publishing: Philadelphia, 1998.

- ↑ Carretero, A.S.; Cruces-Blanco, C.; Ramirez, S.C.; Pancorbo, A.C.; Gutierrez, A.F. J. Agric. Food. Chem. 2004, 52, 5791.

- ↑ Cavazza, A.; Corradini, C.; Lauria, A.; Nicoletti, I. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000, 48, 3324.

- ↑ Rodrigues, M.R.A.; Caramao, E.B.; Arce, L.; Rios, A.; Valcarcel, M. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 425.

- ↑ Simms, P.J.; Jeffries, C.T.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Arrhenius, T.; Nadzan, A.M. J. Comb. Chem. 2001, 3, 427.

Sources

- Kealey, D.;Haines P.J.; instant notes, Analytical Chemistry page 182-188

| |||||||||||||||||