Meroë

| Archaeological Sites of the Island of Meroe | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

| |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, vi, v |

| Reference | 1336 |

| UNESCO region | Africa |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2011 (35th Session) |

Coordinates: 16°56′N 33°45′E / 16.94°N 33.75°E

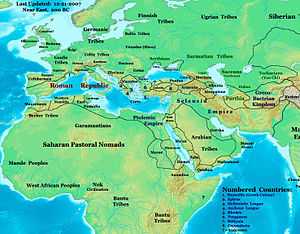

Meroë /ˈmɛroʊeɪ/ (also spelled Meroe[1][2]) (Meroitic: Medewi or Bedewi; Arabic: مرواه Meruwah and مروى Meruwi, Ancient Greek: Μερόη, Meróē) is an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile about 6 km north-east of the Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, approximately 200 km north-east of Khartoum. Near the site are a group of villages called Bagrawiyah. This city was the capital of the Kingdom of Kush for several centuries. The Kushitic Kingdom of Meroë gave its name to the Island of Meroë, which was the modern region of Butana, a region bounded by the Nile (from the Atbarah River to Khartoum), the Atbarah and the Blue Nile.

The city of Meroë was on the edge of Butana and there were two other Meroitic cities in Butana, Musawwarat es-Sufra and Naqa.[3][4] The presence of numerous Meroitic sites within the western Butana region and on the border of Butana proper is significant to the settlement of the core of the developed region. The orientation of these settlements exhibit the exercise of state power over subsistence production.[5]

The kingdom of Kush which housed the city of Meroe represents one of a series of early states located within the middle nile. It is one of the earliest and most impressive states found south of the Sahara. Looking at the specificity of the surrounding early states within the middle nile, ones understanding of Meroe in combination with the historical developments of other historic states may be enhanced through looking at the development of power relation characteristics within other states of Sudanic Africa. [6]

The site of the city of Meroë is marked by more than two hundred pyramids in three groups, of which many are in ruins. They are identified as Nubian pyramids because of their distinctive size and proportions.

History

Meroë was the southern capital of the Napata/Meroitic Kingdom, that spanned the period c. 800 BC — c. 350 AD. According to partially deciphered Meroitic texts, the name of the city was Medewi or Bedewi (Török, 1998).

Excavations revealed evidence of important, high ranking Kushite burials, from the Napata Period (c. 800 - c. 280 BC) in the vicinity of the settlement called the Western cemetery.

The culture of Meroë developed from the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, which originated in Kush. The importance of the town gradually increased from the beginning of the Meroitic Period, especially from the reign of Arrakkamani (c. 280 BC) when the royal burial ground was transferred to Meroë from Napata (Jebel Barkal).

The city of Meroe was located along the middle nile which is of much importance due to the annual flooding of the nile river valley and the connection to many major river systems such as the Niger which aided with the production of pottery and iron characteristic to the Meroitic kingdom that allowed for the rise in power of its people.[7]

Rome's conquest of Egypt led to border skirmishes and incursions by Meroë beyond the Roman borders. In 23 BC the Roman governor of Egypt, Publius Petronius, to end the Meroitic raids, invaded Nubia in response to a Nubian attack on southern Egypt, pillaging the north of the region and sacking Napata (22 BC) before returning home. In retaliation, the Nubians crossed the lower border of Egypt and looted many statues (among other things) from the Egyptian towns near the first cataract of the Nile at Aswan. Roman forces later reclaimed many of the statues intact, and others were returned following the peace treaty signed in 22 BCE between Rome and Meroe. One looted head though, from a statue of the emperor Augustus, was buried under the steps of a temple. It is now kept in the British Museum.[8]

The next recorded contact between Rome and Meroe was in the autumn of AD 61. The Emperor Nero sent a party of Praetorian soldiers under the command of a tribune and two centurions into this country, who reached the city of Meroe where they were given an escort, then proceeded up the White Nile until they encountered the swamps of the Sudd. This marked the limit of Roman penetration into Africa.[9]

The period following Petronius' punitive expedition is marked by abundant trade finds at sites in Meroe. L.P. Kirwan provides a short list of finds from archeological sites in that country.[10] However, the kingdom of Meroe began to fade as a power by the 1st or 2nd century AD, sapped by the war with Roman Egypt and the decline of its traditional industries.[11]

Meroe is mentioned succinctly in the 1st century AD Periplus of the Erythraean Sea:

"2. On the right-hand coast next below Berenice is the country of the Berbers. Along the shore are the Fish-Eaters, living in scattered caves in the narrow valleys. Farther inland are the Berbers, and beyond them the Wild-flesh-Eaters and Calf-Eaters, each tribe governed by its chief; and behind them, farther inland, in the country towards the west, there lies a city called Meroe."—Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, Chap.2

The last period of the city is marked by the victory stele of an unnamed ruler of Aksum (almost certainly Ezana) erected at the site of Meroë; from his description, in Greek, that he was "King of the Aksumites and the Omerites," (i.e. of Aksum and Himyar) it is likely this king ruled sometime around 330.

Civilization

Meroë was the base of a flourishing kingdom whose wealth was due to a strong iron industry, and international trade involving India and China.[12] So much metalworking went on in Meroë, through the working of bloomeries and possibly blast furnaces, that it has even been called "the Birmingham of Africa" because of its vast production and trade of iron to the rest of Africa and other international trade partners.

The centralized control of production within the Meroitic empire and distribution of certain crafts and manufactures may have been politically important with their iron industry and pottery crafts gaining the most significant attention. The Meroitic settlements were oriented in a savannah orientation with the varying of permanent and less permanent agricultural settlements can be attributed to the exploitation of rainlands and savannah-oriented forms of subsistence.[13]

At the time, iron was one of the most important metals worldwide, and Meroitic metalworkers were among the best in the world. Meroë also exported textiles and jewelry. Their textiles were based on cotton and working on this product reached its highest achievement in Nubia around 400 BC. Furthermore, Nubia was very rich in gold. It is possible that the Egyptian word for gold, nub, was the source of name of Nubia. Trade in "exotic" animals from farther south in Africa was another feature of their economy.

Apart from the iron trade, pottery was a widespread and prominent industry in the Meroe kingdom. The production of fine and elaborated decorated wares was a strong tradition within the middle nile. Such productions carried considerable social significance and are believed to be involved in mortuary rites. The long history of goods imported into the Meroitic empire and their subsequent distribution provides insight into the social and political workings of the Meroitic state. The major determinant of production was attributed to the availability of labor rather than the political power associated with land. Power was associated with control of people rather than control of territory. [14]

The Egyptian import, the water-moving wheel, the sakia, was used to move water, in conjunction with irrigation, to increase crop production.[15]

At the peak, the rulers of Meroë controlled the Nile valley north to south over a straight line distance of more than 1,000 km (620 mi).[16]

The King of Meroë was an autocratic ruler who shared his authority only with the Queen Mother, or Candace. However, the role of the Queen Mother remains obscure. The administration consisted of treasurers, seal bearers, heads of archives and chief scribes, among others.

By the 3rd century BC a new indigenous alphabet, the Meroitic, consisting of twenty-three letters, replaced Egyptian script. The Meroitic script is an alphabetic script originally derived from Egyptian hieroglyphs, used to write the Meroitic language of the Kingdom of Meroë/Kush. It was developed in the Napatan Period (about 700 - 300 BC), and first appears in the 2nd century BC. For a time, it was also possibly used to write the Nubian language of the successor Nubian kingdoms.[17]

Although the people of Meroë also had southern deities such as Apedemak, the lion-son of Sekhmet (or Bast, depending upon the region), they also continued worshipping Egyptian deities they had brought with them, such as Amun, Tefnut, Horus, Isis, Thoth and Satis, though to a lesser extent.

The collapse of their external trade with other Sudanic states may be considered as one of the prime causes of the decline of royal power and disintegration of the Meroitic state in the 3rd and 4th centuries A.D. [18]

Archaeology

- For a list of pyramids and their owners, see Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah)

The site of Meroë was brought to the knowledge of Europeans in 1821 by the French mineralogist Frédéric Cailliaud (1787–1869), who published an illustrated in-folio describing the ruins. His work included the first publication of the southernmost known Latin inscription.[19] Some treasure-hunting excavations were executed on a small scale in 1834 by Giuseppe Ferlini, who discovered (or professed to discover) various antiquities, chiefly in the form of jewelry, now in the museums of Berlin and Munich.

The ruins were examined more carefully in 1844 by Karl Richard Lepsius, who took many plans, sketches and copies, besides actual antiquities, to Berlin.

Further excavations were carried on by E. A. Wallis Budge in the years 1902 and 1905, the results of which are recorded in his work, The Egyptian Sudan: its History and Monuments (London, 1907). Troops furnished by Sir Reginald Wingate, governor of Sudan, made paths to and between the pyramids and sank shafts.

It was found that the pyramids were commonly built over sepulchral chambers, containing the remains of bodies, either burned, or buried without being mummified. The most interesting objects found were the reliefs on the chapel walls, already described by Lepsius, which present the names and representations of their queens, Candaces, or the Nubian Kentakes, some kings and some chapters of the Book of the Dead; some stelae with inscriptions in the Meroitic language; and some vessels of metal and earthenware. The best of the reliefs were taken down stone by stone in 1905, and set up partly in the British Museum, and partly in the museum at Khartoum.

In 1910, in consequence of a report by Archibald Sayce, excavations were commenced in the mounds of the town, and in the necropolis, by John Garstang, on behalf of the University of Liverpool. Garstang discovered the ruins of a palace and several temples built by the Meroite rulers.

World Heritage listing

In June 2011, the Archeological Sites of Meroë were listed by UNESCO as World Heritage Sites.[20]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Meroe, Encyclopædia Britannica, v.15, p.197, Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., William Benton, London, 1969.

- ↑ Meroe, Encyclopedia Americana, v.18, p.677, Encyclopedia Americana Corporation, New York, 1961.

- ↑ ""The Island of Meroe", UNESCO World Heritage". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ "Osman Elkhair and Imad-eldin Ali, ''Ancient Meroe Site: Naqa and Musawwarat es-Sufra'' (recent photographs)". Ancientsudan.org. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/183595

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/183595

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/183595

- ↑ "Bronze head of Augustus". British Museum. 1999. Retrieved 2008-06-14.

- ↑ L.P. Kirwan, "Rome beyond The Southern Egyptian Frontier", Geographical Journal, 123 (1957), pp. 16f

- ↑ Kirwan, "Rome beyond", pp. 18f

- ↑ ""Nubia", ''BBC World Service''". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ "Lecture 30: ANCIENT AFRICA Lectures contributed by Steve Stofferan and Sarah Wood, Purdue University". Web.ics.purdue.edu. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/183595

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/183595

- ↑ Trudy Ring, Robert M. Salkin, Sharon La Boda, International Dictionary of Historic Places

- ↑ Adams, Nubia, p. 302.

- ↑ ""Meroe: Writing", ''Digital Egypt,'' University College, London". Digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/183595

- ↑ CIL III, 83. This inscription was subsequently published by Lepsius, who brought the stone back to Berlin. Although thought lost, it was recently rediscovered in the Skulpturensammlung und Museum für Byzantinische Kunst of the Staatliche Museen in Berlin; see Adam Łajtar and Jacques van der Vliet, "Rome-Meroe-Berlin. The Southernmost Latin Inscription Rediscovered ('CIL' III 83)", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 157 (2006), pp. 193-198

- ↑ "World Heritage Sites: Meröe". Retrieved 14 July 2011.

References

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press - Bianchi, Steven (1994). The Nubians: People of the ancient Nile. Brookfield, Conn.: Millbrook Press. ISBN 1-56294-356-1.

- Davidson, Basil (1966). Africa, History of A Continent. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 41–58.

- Adams, W. Y. (1977), Nubia: Corridor to Africa, London: Allen Lane, pp. 294–432.

- Shinnie, P. L. (1967). Meroe, a civilization of Sudan. Ancient People and Places 55. London/New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Török, László (1997). The Kingdom of Kush: Handbook of the Napatan-Meroitic Civilization. Handbuch der Orientalistik. Erste Abteilung, Nahe und der Mittlere Osten 31. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10448-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Meroë. |

- LearningSites.com - Gebel Barkal

- UNESCO World Heritage - Gebel Barkal and the Sites of the Napatan Region

- Nubia Museum - Merotic Empire

- (French) Voyage au pays des pharaons noirs Travel in Sudan and notes on Nubian history