Mercury sulfide

| Mercury sulfide | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

| IUPAC name Mercury sulfide | ||

| Identifiers | ||

| CAS number | 1344-48-5 | |

| PubChem | 62402 | |

| Properties | ||

| Molecular formula | HgS | |

| Molar mass | 232.66 g/mol | |

| Density | 8.10 g/cm3 | |

| Melting point | 580 °C decomp. | |

| Solubility in water | insoluble | |

| Band gap | 2.1 eV (direct, α-HgS) [1] | |

| Refractive index (nD) | w=2.905, e=3.256, bire=0.3510 (α-HgS) [2] | |

| Thermochemistry | ||

| Std enthalpy of formation ΔfH |

−58 kJ·mol−1[3] | |

| Standard molar entropy S |

78 J·mol−1·K−1[3] | |

| Hazards | ||

| MSDS | ICSC 0981 | |

| EU Index | 080-002-00-6 | |

| EU classification | Very toxic (T+) Dangerous for the environment (N) | |

| R-phrases | R26/27/28, R33, R50/53 | |

| S-phrases | (S1/2), S13, S28, S45, S60, S61 | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable | |

| Related compounds | ||

| Other anions | Mercury oxide Mercury selenide Mercury telluride | |

| Other cations | Zinc sulfide Cadmium sulfide | |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C (77 °F), 100 kPa) | ||

| Infobox references | ||

Mercury sulfide, mercuric sulfide, mercury sulphide, or mercury(II) sulfide is a chemical compound composed of the chemical elements mercury and sulfur. It is represented by the chemical formula HgS. It is virtually insoluble in water.[4]

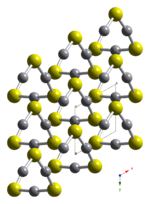

Crystal structure

HgS is dimorphic with two crystal forms:

- red cinnabar (α-HgS, hexagonal, hP6, P3221), is the form in which mercury is most commonly found in nature.

- black, metacinnabar (β-HgS), is less common in nature and adopts the zinc blende (T2d-F43m) crystal structure.

Crystals of red, α-HgS, are optically active. This is caused by the Hg-S helices in the structure.[5]

Preparation and chemistry

β-HgS is precipitated as a black powder when H2S is bubbled through solutions of Hg(II) salts.[6] β-HgS is unreactive to all but concentrated acids.[4]

Mercury metal is produced from the cinnabar ore by roasting in air and condensing the vapour.[4]

Uses

α-HgS is used as a red pigment when it is known as vermilion. Vermilion is known to darken and this has been ascribed to conversion from red α-HgS to black β-HgS. Investigations at Pompeii where red walls when originally excavated have darkened has been ascribed to the formation of Hg-Cl compounds (e.g., corderoite, calomel, and terlinguaite) and calcium sulfate, gypsum, rather than β-HgS, which was not detected.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ L. I. Berger, Semiconductor Materials (1997) CRC Press ISBN 0-8493-8912-7

- ↑ Webminerals

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A22. ISBN 0-618-94690-X.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1984). Chemistry of the Elements. Oxford: Pergamon Press. p. 1406. ISBN 0-08-022057-6.

- ↑ Glazer, A. M.; Stadnicka K. (1986). "On the origin of optical activity in crystal structures". J. Appl. Cryst. 19 (2): 108–122. doi:10.1107/S0021889886089823.

- ↑ Cotton, F. Albert; Wilkinson, Geoffrey; Murillo, Carlos A.; Bochmann, Manfred (1999), Advanced Inorganic Chemistry (6th ed.), New York: Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0-471-19957-5

- ↑ Cotte, M; Susini J, Metrich N, Moscato A, Gratziu C, Bertagnini A, Pagano M (2006). "Blackening of Pompeian Cinnabar Paintings: X-ray Microspectroscopy Analysis". Anal. Chem. 78 (21): 7484–7492. doi:10.1021/ac0612224. PMID 17073416.

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory - Mercury and compounds Fact Sheet - link leads to "page not found"

| |||||||||||||||||||