Mercator projection

The Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Flemish geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as straight segments which conserve the angles with the meridians. While the linear scale is equal in all directions around any point, thus preserving the angles and the shapes of small objects (which makes the projection conformal), the Mercator projection distorts the size and shape of large objects, as the scale increases from the Equator to the poles, where it becomes infinite.

Properties and historical details

Mercator's 1569 edition was a large planisphere measuring 202 by 124 cm, printed in eighteen separate sheets. As in all cylindrical projections, parallels and meridians are straight and perpendicular to each other. In accomplishing this, the unavoidable east-west stretching of the map, which increases as distance away from the equator increases, is accompanied in the Mercator projection by a corresponding north-south stretching, so that at every point location, the east-west scale is the same as the north-south scale, making the projection conformal. A Mercator map can never fully show the polar areas, since linear scale becomes infinitely high at the poles. Being a conformal projection, angles are preserved around all locations. However scale varies from place to place, distorting the size of geographical objects and conveying a distorted idea of the overall geometry of the planet. At latitudes greater than 70° north or south, the Mercator projection is practically unusable.

All lines of constant bearing (rhumbs or loxodromes—those making constant angles with the meridians) are represented by straight segments on a Mercator map. The two properties, conformality and straight rhumb lines, make this projection uniquely suited to marine navigation: courses and bearings are measured using wind roses or protractors, and the corresponding directions are easily transferred from point to point, on the map, with the help of a parallel ruler or a pair of navigational protractor triangles.

The name and explanations given by Mercator to his world map (Nova et Aucta Orbis Terrae Descriptio ad Usum Navigantium Emendata: "new and augmented description of Earth corrected for the use of sailors") show that it was expressly conceived for the use of marine navigation. Although the method of construction is not explained by the author, Mercator probably used a graphical method, transferring some rhumb lines previously plotted on a globe to a square graticule, and then adjusting the spacing between parallels so that those lines became straight, making the same angle with the meridians as in the globe.

The development of the Mercator projection represented a major breakthrough in the nautical cartography of the 16th century. However, it was much ahead of its time, since the old navigational and surveying techniques were not compatible with its use in navigation. Two main problems prevented its immediate application: the impossibility of determining the longitude at sea with adequate accuracy and the fact that magnetic directions, instead of geographical directions, were used in navigation. Only in the middle of the 18th century, after the marine chronometer was invented and the spatial distribution of magnetic declination was known, could the Mercator projection be fully adopted by navigators.

Several authors are associated with the development of Mercator projection:

- German Erhard Etzlaub (c. 1460–1532), who had engraved miniature "compass maps" (about 10×8 cm) of Europe and parts of Africa, latitudes 67°–0°, to allow adjustment of his portable pocket-size sundials, was for decades declared to have designed "a projection identical to Mercator's".

- Portuguese mathematician and cosmographer Pedro Nunes (1502–1578), who first described the loxodrome and its use in marine navigation, and suggested the construction of a nautical atlas composed of several large-scale sheets in the cylindrical equidistant projection as a way to minimize distortion of directions. If these sheets were brought to the same scale and assembled an approximation of the Mercator projection would be obtained (1537).

- English mathematician Edward Wright (c. 1558–1615), who published accurate tables for its construction (1599, 1610).

- English mathematicians Thomas Harriot (1560–1621) and Henry Bond (c.1600–1678) who, independently (c.1600 and 1645), associated the Mercator projection with its modern logarithmic formula, later deduced by calculus.

Uses

As on all map projections, shapes or sizes are distortions of the true layout of the Earth's surface. The Mercator projection exaggerates areas far from the equator. For example:

- Greenland takes as much space on the map as Africa, when in reality Africa's area is 14 times greater and Greenland's is comparable to Algeria's alone.

- Alaska takes as much area on the map as Brazil, when Brazil's area is nearly five times that of Alaska.

- Finland appears with a greater north-south extent than India, although India's is greater.

- Antarctica appears as the biggest continent, although it is actually the fifth in terms of area.

Although the Mercator projection is still used commonly for navigation, due to its unique properties, cartographers agree that it is not suited to general reference world maps due to its distortion of land area. Mercator himself used the equal-area sinusoidal projection to show relative areas. As a result of these criticisms, modern atlases no longer use the Mercator projection for world maps or for areas distant from the equator, preferring other cylindrical projections, or forms of equal-area projection. The Mercator projection is still commonly used for areas near the equator, however, where distortion is minimal.

Arno Peters stirred controversy when he proposed what is now usually called the Gall–Peters projection as the alternative to the Mercator. The projection he promoted is a specific parameterization of the cylindrical equal-area projection. In response, a 1989 resolution by seven North American geographical groups deprecated the use of cylindrical projections for general purpose world maps, which would include both the Mercator and the Gall–Peters.[1]

Many major online street mapping services (Bing Maps, OpenStreetMap, Google Maps, MapQuest, Yahoo Maps, and others) use a variant of the Mercator projection for their map images.[2] Despite its obvious scale variation at small scales, the projection is well-suited as an interactive world map that can be zoomed seamlessly to large-scale (local) maps, where there is relatively little distortion due to the variant projection's near-conformality.

The major online street mapping services tiling systems display most of the world at the lowest zoom level as a single square image, excluding the polar regions by truncation at latitudes of φmax = ±85.05113°. (See below.) Latitude values outside this range are mapped using a different relationship that doesn't diverge at φ = ±90°.

Mathematics of the Mercator projection

The spherical model

Although the surface of Earth is best modelled by an oblate ellipsoid of revolution, for small scale maps the ellipsoid is approximated by a sphere of radius a. Many different ways exist for calculating a. The simplest include (a) the equatorial radius of the ellipsoid, (b) the arithmetic or geometric mean of the semi-axes of the ellipsoid, (c) the radius of the sphere having the same volume as the ellipsoid.[3] The range of all possible choices is about 35 km, but for small scale (large region) applications the variation may be ignored, and mean values of 6,371 km and 40,030 km may be taken for the radius and circumference respectively. These are the values used for numerical examples in later sections. Only high-accuracy cartography on large scale maps requires an ellipsoidal model.

Cylindrical projections

The spherical approximation of Earth with radius a can be modelled by a smaller sphere of radius R, called the globe in this section. The globe determines the scale of the map. The various cylindrical projections specify how the geographic detail is transferred from the globe to a cylinder tangential to it at the equator. The cylinder is then unrolled to give the planar map.[4][5] The fraction R/a is called the representative fraction (RF) or the principal scale of the projection. For example, a Mercator map printed in a book might have an equatorial width of 13.4 cm corresponding to a globe radius of 2.13 cm and an RF of approximately 1/300M (M is used as an abbreviation for 1,000,000 in writing an RF) whereas Mercator's original 1569 map has a width of 198 cm corresponding to a globe radius of 31.5 cm and an RF of about 1/20M.

A cylindrical map projection is specified by formulæ linking the geographic coordinates of latitude φ and longitude λ to Cartesian coordinates on the map with origin on the equator and x-axis along the equator. By construction, all points on the same meridian lie on the same generator[6] of the cylinder at a constant value of x, but the distance y along the generator (measured from the equator) is an arbitrary[7] function of latitude, y(φ). In general this function does not describe the geometrical projection (as of light rays onto a screen) from the centre of the globe to the cylinder, which is only one of an unlimited number of ways to conceptually project a cylindrical map.

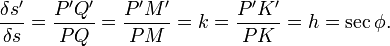

Since the cylinder is tangential to the globe at the equator, the scale factor between globe and cylinder is unity on the equator but nowhere else. In particular since the radius of a parallel, or circle of latitude, is R cos φ, the corresponding parallel on the map must have been stretched by a factor of 1/cos φ = sec φ. This scale factor on the parallel is conventionally denoted by k and the corresponding scale factor on the meridian is denoted by h.[8]

Small element geometry

The relations between y(φ) and properties of the projection, such as the transformation of angles and the variation in scale, follow from the geometry of corresponding small elements on the globe and map. The figure below shows a point P at latitude φ and longitude λ on the globe and a nearby point Q at latitude φ+δφ and longitude λ+δλ. The vertical lines PK and MQ are arcs of meridians of length Rδφ.[9] The horizontal lines PM and KQ are arcs of parallels of length R(cos φ)δλ.[10] The corresponding points on the projection define a rectangle of width δx and height δy.

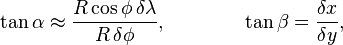

For small elements, the angle PKQ is approximately a right angle and therefore

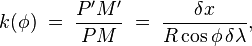

The previously mentioned scaling factors from globe to cylinder are given by

- parallel scale factor

- meridian scale factor

Since the meridians are mapped to lines of constant x we must have x=R(λ−λ0) and δx=Rδλ, (λ in radians). Therefore in the limit of infinitesimally small elements

Derivation of the Mercator projection

The choice of the function y(φ) for the Mercator projection is determined by the demand that the projection be conformal, a condition which can be defined in two equivalent ways:

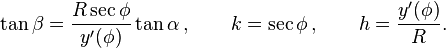

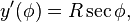

- Equality of angles. The condition that a sailing course of constant azimuth α on the globe is mapped into a constant grid bearing β on the map. Setting α=β in the above equations gives y'(φ)=R secφ.

- Isotropy of scale factors. This is the statement that the point scale factor is independent of direction so that small shapes are preserved by the projection. Setting h=k in the above equations again gives y'(φ)=R secφ.

Integrating the equation

with y(0)=0, by using integral tables[11] or elementary methods,[12] gives y(φ). Therefore

In the first equation λ0 is the longitude of an arbitrary central meridian usually, but not always, that of Greenwich (i.e., zero). The difference (λ−λ0) is in radians.

The function y(φ) is plotted alongside for the case R=1: it tends to infinity at the poles. The linear y-axis values are not usually shown on printed maps; instead some maps show the non-linear scale of latitude values on the right. More often than not the maps show only a graticule of selected meridians and parallels

Inverse transformations

The expression on the right of the second equation defines the gudermannian function; i.e., φ=gd(y/R): the direct equation may therefore be written as y=R.gd−1(φ).[11]

Alternative expressions

There are many alternative expressions for y(φ), all derived by elementary manipulations.[12]

Corresponding inverses are:

For angles expressed in degrees:

The above formulae are written in terms of the globe radius R. It is often convenient to work directly with the map width W=2πR. For example the basic transformation equations become

Truncation and aspect ratio

The ordinate y of the Mercator becomes infinite at the poles and the map must be truncated at some latitude less than ninety degrees. This need not be done symmetrically. Mercator's original map is truncated at 80°N and 66°S with the result that European countries were moved towards the centre of the map. The aspect ratio of his map is 198/120=1.65. Even more extreme truncations have been used: a Finnish school atlas was truncated at approximately 76°N and 56°S, an aspect ratio of 1.97.

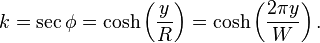

Much web based mapping uses a zoomable version of the Mercator projection with an aspect ratio of unity. In this case the maximum latitude attained must correspond to y=±W/2, or equivalently y/R=π. Any of the inverse transformation formulae may be used to calculate the corresponding latitudes:

Scale factor

The figure comparing the infinitesimal elements on globe and projection shows that when α=β the triangles PQM and P'Q'M' are similar so that the scale factor in an arbitrary direction is the same as the parallel and meridian scale factors:

This result holds for an arbitrary direction: the definition of isotropy of the point scale factor. The graph shows the variation of the scale factor with latitude. Some numerical values are listed below.

- at latitude 30° the scale factor is k= sec 30°=1.15,

- at latitude 45° the scale factor is k= sec 45°=1.41,

- at latitude 60° the scale factor is k= sec 60°=2,

- at latitude 80° the scale factor is k= sec 80°=5.76,

- at latitude 85° the scale factor is k= sec 85°=11.5

Working from the projected map requires the scale factor in terms of the Mercator ordinate y (unless the map is provided with an explicit latitude scale). Since ruler measurements can furnish the map ordinate y and also the width W of the map then y/R=2πy/W and the scale factor is determined using one of the alternative forms for the forms of the inverse transformation:

The variation with latitude is sometimes indicated by multiple bar scales as shown below and, for example, on a Finnish school atlas. The interpretation of such bar scales is non-trivial. See the discussion on distance formulae below.

Area scale

The area scale factor is the product of the parallel and meridian scales hk = sec2φ. For Greenland, taking 73° as a median latitude, hk = 11.7. For Australia, taking 25° as a median latitude, hk = 1.2. For Great Britain, taking 55° as a median latitude, hk = 3.04.

Distortion

The classic way of showing the distortion inherent in a projection is to use Tissot's indicatrix. Nicolas Tissot noted that for cylindrical projections the scale factors at a point, specified by the numbers h and k, define an ellipse at that point of the projection. The axes of the ellipse are aligned to the meridians and parallels.[8][13][14] For the Mercator projection, h=k, so the ellipses degenerate into circles with radius proportional to the value of the scale factor for that latitude. These circles are then placed on the projected map with an arbitrary overall scale (because of the extreme variation in scale) but correct relative sizes.

Accuracy

One measure of a map's accuracy is a comparison of the length of corresponding line elements on the map and globe. Therefore, by construction, the Mercator projection is perfectly accurate, k=1, along the equator and nowhere else. At a latitude of ±25° the value of sec φ is about 1.1 and therefore the projection may be deemed accurate to within 10% in a strip of width 50° centred on the equator. Narrower strips are better: sec 8°=1.01, so a strip of width 16° (centred on the equator) is accurate to within 1% or 1 part in 100. Similarly sec 2.56°=1.001, so a strip of width 5.12° (centred on the equator) is accurate to within 0.1% or 1 part in 1,000. Therefore the Mercator projection is adequate for mapping countries close to the equator.

Secant projection

In a secant (in the sense of cutting) Mercator projection the globe is projected to a cylinder which cuts the sphere at two parallels with latitudes ±φ1. The scale is now true at these latitudes whereas parallels between these latitudes are contracted by the projection and their scale factor must be less than one. The result is that deviation of the scale from unity is reduced over a wider range of latitudes.

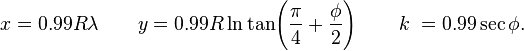

An example of such a projection is

The scale on the equator is 0.99; the scale is k=1 at a latitude of approximately ±8° (the value of φ1); the scale is k=1.01 at a latitude of approximately ±11.4°. Therefore the projection has an accuracy of 1%, over a wider strip of 22° compared with the 16° of the normal (tangent) projection. This is a standard technique of extending the region over which a map projection has a given accuracy.

Generalization to the ellipsoid

When the Earth is modelled by an ellipsoid (of revolution) the Mercator projection must be modified if it is to remain conformal. The transformation equations and scale factor for the non-secant version are[15]

The scale factor is unity on the equator, as it must be since the cylinder is tangential to the ellipsoid at the equator. The ellipsoidal correction of the scale factor increases with latitude but it is never greater than e2, a correction of less than 1%. (The value of e2 is about 0.006 for all reference ellipsoids.) This is much smaller than the scale inaccuracy, except very close to the equator. Only accurate Mercator projections of regions near the equator will necessitate the ellipsoidal corrections.

Formulae for distance

Converting ruler distance on the Mercator map into true (great circle) distance on the sphere is straightforward along the equator but nowhere else. One problem is the variation of scale with latitude, and another is that straight lines on the map (rhumb lines), other than the meridians or the equator, do not correspond to great circles.

The distinction between rhumb (sailing) distance and great circle (true) distance was clearly understood by Mercator. (See Legend 12 on the 1569 map.) He stressed that the rhumb line distance is an acceptable approximation for true great circle distance for courses of short or moderate distance, particularly at lower latitudes. He even quantifies his statement: "When the great circle distances which are to be measured in the vicinity of the equator do not exceed 20 degrees of a great circle, or 15 degrees near Spain and France, or 8 and even 10 degrees in northern parts it is convenient to use rhumb line distances".

For a ruler measurement of a short line, with midpoint at latitude φ, where the scale factor is k=secφ = 1/cos φ:

- True distance = rhumb distance ≅ ruler distance × cos φ / RF. (short lines)

With radius and great circle circumference equal to 6,371 km and 40,030 km respectively an RF of 1/300M, for which R=2.12 cm and W=13.34 cm, implies that a ruler measurement of 3 mm. in any direction from a point on the equator corresponds to approximately 900 km. The corresponding distances for latitudes 20°, 40°, 60° and 80° are 846 km, 689 km, 450 km and 156 km respectively.

Longer distances require various approaches.

On the equator

Scale is unity on the equator (for a non-secant projection). Therefore interpreting ruler measurements on the equator is simple:

- True distance = ruler distance / RF (equator)

For the above model, with RF=1/300M, 1 cm corresponds to 3,000 km.

On other parallels

On any other parallel the scale factor is sec φ so that

- Parallel distance = ruler distance × cos φ / RF (parallel).

For the above model 1 cm corresponds to 1,500 km at a latitude of 60°.

This is not the shortest distance between the chosen endpoints on the parallel because a parallel is not a great circle. The difference is small for short distances but increases as λ, the longitudinal separation, increases. For two points, A and B, separated by 10° of longitude on the parallel at 60° the distance along the parallel is approximately 0.5 km greater than the great circle distance. (The distance AB along the parallel is (a cosφ) λ. The length of the chord AB is 2(a cosφ)sin(λ/2). This chord subtends an angle at the centre equal to 2arcsin( cosφ sin(λ/2)) and the great circle distance between A and B is 2a arcsin( cosφ sin(λ/2)).) In the extreme case where the longitudinal separation is 180°, the distance along the parallel is one half of the circumference of that parallel; i.e., 10,007.5 km. On the other hand the geodesic between these points is a great circle arc through the pole subtending an angle of 60° at the center: the length of this arc is one sixth of the great circle circumference, about 6,672 km. The difference is 3,338 km so the ruler distance measured from the map is quite misleading even after correcting for the latitude variation of the scale factor.

On a meridian

A meridian of the map is a great circle on the globe but the continuous scale variation means ruler measurement alone cannot yield the true distance between distant points on the meridian. However, if the map is marked with an accurate and finely spaced latitude scale from which the latitude may be read directly—as is the case for the Mercator 1569 world map (sheets 3, 9, 15) and all subsequent nautical charts—the meridian distance between two latitudes φ1 and φ2 is simply

If the latitudes of the end points cannot be determined with confidence then they can be found instead by calculation on the ruler distance. Calling the ruler distances of the end points on the map meridian as measured from the equator y1 and y2, the true distance between these points on the sphere is given by using any one of the inverse Mercator formulæ:

where R may be calculated from the width W of the map by R=W/2π. For example, on a map with R=1 the values of y=0, 1, 2, 3 correspond to latitudes of φ=0°, 50°, 75°, 84° and therefore the successive intervals of 1 cm on the map correspond to latitude intervals on the globe of 50°, 25°, 9° and distances of 5,560 km, 2,780 km, and 1,000 km on the Earth.

On a rhumb

A straight line on the Mercator map at angle α to the meridians is a rhumb line. When α=π/2 or 3π/2 the rhumb corresponds to one of the parallels; only one, the equator, is a great circle. When α=0 or π it corresponds to a meridian great circle (if continued around the Earth). For all other values it is a spiral from pole to pole on the globe intersecting all meridians at the same angle, and is thus not a great circle.[12] This section discusses only the last of these cases.

If α is neither 0 nor π then the above figure of the infinitesimal elements shows that the length of an infinitesimal rhumb line on the sphere between latitudes φ; and φ+δφ is a secα δφ. Since α is constant on the rhumb this expression can be integrated to give, for finite rhumb lines on the Earth:

Once again, if Δφ may be read directly from an accurate latitude scale on the map, then the rhumb distance between map points with latitudes φ1 and φ2 is given by the above. If there is no such scale then the ruler distances between the end points and the equator, y1 and y2, give the result via an inverse formula:

These formulæ give rhumb distances on the sphere which may differ greatly from true distances whose determination requires more sophisticated calculations.[16]

See also

- List of map projections

- Cartography

- Transverse Mercator projection

- Universal Transverse Mercator coordinate system

- Gall–Peters projection

- Jordan Transverse Mercator

- Nautical chart

- Tissot's indicatrix

Notes

- ↑ American Cartographer. 1989. 16(3): 222–223.

- ↑ http://groups.google.com/group/Google-Maps-API/msg/8222b18e7921f6e6

- ↑ Maling, pages 77–79.

- ↑ Snyder, Working manual pp 37—95.

- ↑ Snyder, Flattening the Earth.

- ↑ A generator of a cylinder is a straight line on the surface parallel to the axis of the cylinder.

- ↑ The function y(φ) is not completely arbitrary: it must be monotonic increasing and antisymmetric (y(−φ)=−y(φ), so that y(0)=0): it is normally continuous with a continuous first derivative.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Snyder. Working Manual, page 20.

- ↑ R is the radius of the globe and φ is measured in radians.

- ↑ λ is measured in radians.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 NIST. See Sections 4.26#ii and 4.23#viii

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Osborne Chapter 2.

- ↑ Snyder, Flattening the Earth, pp 147—149

- ↑ More general example of Tissot's indicatrix: the Winkel tripel projection.

- ↑ Osborne, Chapters 5, 6

- ↑ See great-circle distance, the Vincenty's formulae or Mathworld.

References

- Maling, Derek Hylton (1992), Coordinate Systems and Map Projections (second ed.), Pergamon Press, ISBN 0-08-037233-3.

- Monmonier, Mark (2004), Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection (Hardcover ed.), Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-53431-6

- Olver, F. W.J.; Lozier, D.W.; Boisvert, R.F. et al., eds. (2010), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press

- Osborne, Peter (2013), The Mercator Projections

- Rapp, Richard H (1991), Geometric Geodesy, Part I

- Snyder, John P (1993), Flattening the Earth: Two Thousand Years of Map Projections, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0-226-76747-7

- Snyder, John P. (1987), Map Projections – A Working Manual. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 1395, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. This paper can be downloaded from USGS pages. It gives full details of most projections, together with interesting introductory sections, but it does not derive any of the projections from first principles.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mercator projections. |

- Ad maiorem Gerardi Mercatoris gloriam – contains high-resolution images of the 1569 world map by Mercator.

- Table of examples and properties of all common projections, from radicalcartography.net.

- An interactive Java Applet to study the metric deformations of the Mercator Projection.

- Web Mercator: Non-Conformal, Non-Mercator (Noel Zinn, Hydrometronics LLC)

- Mercator's Projection at University of British Columbia

- Mercator's Projection at Wolfram MathWorld

- Google Maps Coordinates

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

![{\begin{aligned}x&=R(\lambda -\lambda _{0}),\qquad y&=R\ln \left[\tan \left({\frac {\pi }{4}}+{\frac {\phi }{2}}\right)\right].\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/4/d/7/94d75e5b6ab63974b70c73d836e427db.png)

![{\begin{aligned}\lambda &=\lambda _{0}+{\frac {x}{R}},\qquad \phi &=2\tan ^{{-1}}\left[\exp \left({\frac {y}{R}}\right)\right]-{\frac {\pi }{2}}\,.\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/d/f/a/5dfa932b62b3697352a63c102ef69647.png)

![{\begin{aligned}y&=&{\frac {R}{2}}\ln \left[{\frac {1+\sin \phi }{1-\sin \phi }}\right]&=&{R}\ln \left[{\frac {1+\sin \phi }{\cos \phi }}\right]&=R\ln \left(\sec \phi +\tan \phi \right)\\[2ex]&=&R\tanh ^{{-1}}\!\left(\sin \phi \right)&=&R\sinh ^{{-1}}\!\left(\tan \phi \right)&=R\cosh ^{{-1}}\!\left(\sec \phi \right)=R\;{\mbox{gd}}^{{-1}}(\phi ).\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/f/b/8/afb824ce10686d4ab3a76c5d32d4c790.png)

![{\begin{aligned}\phi &=\sin ^{{-1}}\left[\tanh(y/R)\right]=\tan ^{{-1}}\left[\sinh(y/R)\right]=\sec ^{{-1}}\left[\cosh(y/R)\right]={\mbox{gd}}(y/R).\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/e/d/4/ced42dd0f2b2dc0a4e899a8925b329c1.png)

![{\begin{aligned}x={\frac {\pi R(\lambda ^{\circ }-\lambda _{0}^{\circ })}{180}},\qquad \quad y=R\ln \left[\tan \left(45+{\frac {\phi ^{\circ }}{2}}\right)\right].\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/0/c/a/a0cad8aff31dd8bb7592c31c8d702165.png)

![{\begin{aligned}x&={\frac {W}{2\pi }}\left(\lambda -\lambda _{0}\right),\qquad \quad y={\frac {W}{2\pi }}\ln \left[\tan \left({\frac {\pi }{4}}+{\frac {\phi }{2}}\right)\right].\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/4/8/e/248ebac16981c8ed4a609204b98131ba.png)

![\phi =\tan ^{{-1}}\left[\sinh \left({\frac {y}{R}}\right)\right]=\tan ^{{-1}}\left[\sinh \pi \right]=\tan ^{{-1}}\left[11.5487\right]=85.05113^{\circ }.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/7/a/b/27ab9af40f29df8eae70e73d7bbb6325.png)

![{\begin{aligned}x&=R\left(\lambda -\lambda _{0}\right),\\y&=R\ln \left[\tan \left({\frac {\pi }{4}}+{\frac {\phi }{2}}\right)\left({\frac {1-e\sin \phi }{1+e\sin \phi }}\right)^{{e/2}}\right],\\k&=\sec \phi {\sqrt {1-e^{2}\sin ^{2}\phi }}.\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/0/6/c/8/06c883773db47ad3dd173198328682e4.png)

![m_{{12}}=a\left|\tan ^{{-1}}\left[\sinh \left({\frac {y_{1}}{R}}\right)\right]-\tan ^{{-1}}\left[\sinh \left({\frac {y_{2}}{R}}\right)\right]\right|,](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/a/5/0/2a50f819bb56efebe88d7e1550548dd9.png)