Menologium

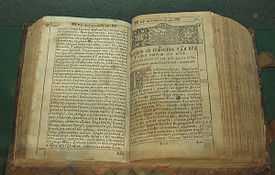

Menologium (from the Greek menológion, from mén "a month"; Latin menologium), also written menology, and menologe, is a service-book used in the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Rite of Constantinople.

From its derivation, menologium means "month-set"; in other words, a book arranged according to the months. Like a good many other liturgical terms (e.g. lectionary), the word has been used in several quite distinct senses.

Definitions

Menologion has several different meanings:

(1) "Menologion" is not infrequently used as synonymous with "Menaion" (pl. Menaia). The Menaia, usually in twelve volumes—one for each month—but sometimes bound in three, form an office-book, which in the Orthodox Church, corresponds roughly to the Proprium Sanctorum of the Latin Breviary. They include all the propers (variable parts) of the services connected with the commemoration of saints and in particular the canons sung at Orthros (Matins and Lauds), including the synaxaries, i. e. the lives of the saints of the day, which are always inserted between the sixth and seventh odes of the canon. The Synaxaries are read in this place very much as the Martyrologium for the day is interpolated in the choral recitation of Prime in the offices of Western Christendom.

(2) Secondly and more frequently, "menologion" is the collection of those lives of the saints just mentioned, without the other liturgical materials. Such a collection, consisting as it does purely of historical matter, bears a considerable resemblance, as will be readily understood, to a Catholic Martyrology, although the lives of the saints are, for the most part, considerably larger and fuller than those found in a Martyrology, while on the other hand the number of entries is smaller. The Menologion of Basil II, a work of early date often referred to in connexion with the history of the Orthodox Offices, is a book of this class.

(3) Frequently the tables of scriptural lessons, arranged according to months and saints' days, which are often found at the beginning of Gospel Books or other lectionaries, are described as menologia. The saints' days are briefly named and the readings indicated beside each; thus the document so designated corresponds much more closely to a calendar than anything else of Western use to which we can compare it.

(4) Finally, the word "menologion" is very widely applied to the collections of long lives of the saints of the Orthodox Church, whenever these lives, as commonly happens, are arranged according to months and days of each month. This arrangement has always been a favourite one also in the great Legendaria of the West, and it might be illustrated from the Acta Sanctorum or the Lives of the Saints by Surius. In the liturgical calendar of the Orthodox Church, September is the first month of the ecclesiastical year, and August is the last.

One of the most important collections of this kind is that made by Symeon Metaphrastes. Father Delehaye and Albert Ehrhard working independently grouped together works which are really attributable to this author, but uncertainty remained to the provenance of his materials, and as to the relation between this collection and certain contracted biographies many of which exist among the manuscripts of our great libraries. The synaxaries, or histories for liturgical use, are nearly all extracted from the older Menologia, but Delehaye, who gave special attention to the study of this class of documents, considered that the authors of these compendia have added, though sparsely, materials of their own, derived from various sources. (See Delehaye in his preface to the "Synaxarium Eccles. Cp.", published as a Propylæum to the Acta Sanctorum for November, lix-lxvi.)

Menologies in the West

The fact that the word martyrology was already consecrated to a liturgical or quasi-liturgical compilation arranged according to months and days, and including only canonized saints and festivals universally received, probably led to the employment of menologium for works of a somewhat analogous character, of private authority, not intended for liturgical use and including the names and elogia of persons in repute for sanctity but not in any sense canonized Saints.

In most of the religious orders it became the custom to commemorate the memory of their dead brethren specially renowned for holiness or learning. In more than one such order during the 17th and 18th centuries, the collection of these short eulogistic biographies was printed under the name of Menologium and generally so arranged as to form a selection for each day of the year. Since they were made by private authority which could not pronounce judgment on the sanctity of those so commemorated, the Church prohibited the reading of these compilations as part of the Divine Office; but this did not prevent the formation of such menologies for private use or even the reading of them aloud in the chapter-house or refectory.

Thus the collection made by the Franciscan Fortunatus Hüber of the abbreviated lives of those of the Friars Minor who had died in the odour of sanctity, printed in 1691 under the title of "Menologium Franciscanum", was evidently intended for public recitation. In lieu of the concluding formula "Et alibi aliorum" etc. of the Roman Martyrology, the compiler suggests (364) as the ferialis terminatio cuiuscumque diei the three verses of the Apocalypse (vii, 9-11) beginning: "Post hæc vidi turbam magnam". The earliest printed work of this kind is possibly that which bears the title "Menologium Carmelitanum" compiled by the Carmelite Saracenus, printed at Bologna in 1627; but this is not arranged day by day in the order of the ecclesiastical year, and it does not include members of the order yet uncanonized. A year or two later, in 1630, Father Crisóstomo Henríquez published at Antwerp his Menologium Cisterciense. That no general custom then existed of reading the Menology at table appears from his remark: "It would not appear unsuitable if it (the Menologium) were read aloud in public or in chapter or at least in the refectory at the beginning of dinner or supper".

Again quite a number of works have been printed under the name Menologium by Fathers of the Society of Jesus, one or other of which it has been and still is the custom of the order to read aloud in the refectory during part of the evening meal. Though Fathers Nuremberg and Nadasi compiled collections of a similar character, they did not bear the name Menologium. The earliest Jesuit compilation which is so styled seems to have been printed in the year 1669. A more elaborate Menologium was that compiled by Father Patrignani in 1730, and great collections were made during the last century by Father de Guilhermy for the production of a series of such menologies, divided according to the groups of provinces of the Society called "Assistencies". The author did not live to complete his task, but the menologies have been published by other hands since his death.

"Menologium" is also any calendar divided into months, as, for example, the Anglo-Saxon Menologium first published by Hickes.

Source

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. newadvent.org - Catholic Encyclopedia

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. newadvent.org - Catholic Encyclopedia

| |||||||||||||||||||||||