Deer park (England)

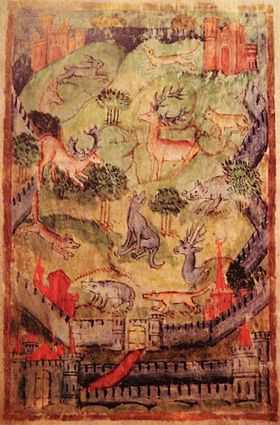

In medieval and Early Modern England, a deer park was an enclosed area containing deer. It was bounded by a ditch and bank with a wooden park pale on top of the bank. The ditch was typically on the inside.[1] Some parks had deer leeps, where there was an external ramp and the inner ditch was constructed on a grander scale, thus allowing deer to enter the park but preventing them from leaving.[2]

History

Some deer parks were established in the Anglo-Saxon era and are mentioned in Anglo-Saxon Charters; these were often called hays.[3]

After the Norman conquest of England in 1066 William the Conqueror seized existing game reserves. Deer parks flourished and prolifereated under the Normans, forming a forerunner of the deer parks that became popular among England's landed gentry. The Domesday Book of 1086 records 36 of them.

Initially the Norman kings maintained an exclusive right to keep and hunt deer and established forest law for this purpose.[4] In due course they also allowed members of the nobility and senior clergy to maintain deer parks. At their peak at the turn of the 14th century, deer parks may have covered 2% of the land area of England.[5]

James I was an enthusiast for hunting but it became less fashionable and popular after the Civil War. The number of deer parks then declined, contemporary books document other more profitable uses for such an estate.[6] During the 18th century many deer parks were landscaped, where deer then became optional within larger country parks several of which created or enlarged from wealth from trade and colonisation in the British Empire, while later mostly giving way to profitable agriculture dependent on crop prices, a workforce attracted elsewhere following increasing industrialization. This created pressure to sell off parts or divide such estates while rural population growth pushed up poor law rates (particularly outdoor relief and the Labour Rate) and urban poverty led to the introduction of lump sum capital taxation such as Inheritance Tax and a shift in power away from the aristocracy.[7]

Deer parks are notable landscape features in their own right. However, where they have survived into the 20th century, the lack of ploughing or development has often preserved other features within the park,[8] including barrows (tumuli), roman roads and abandoned villages.

Status

To establish a deer park a Royal licence was required, occasionally called a licence to empark — especially if the park was in or near a royal forest. Because of their cost and exclusivity, deer parks became status symbols. Since deer were almost all kept within exclusive hunting reserves used as aristocratic playgrounds, there was no legitimate market for venison.[9] Thus the ability to eat venison or give it to others was also a status symbol. Consequently, many deer parks were maintained for the supply of venison, rather than hunting the deer.

Form

Deer parks could vary in size from a circumference of many miles down to what amounted to little more than a deer padock.[10] The landscape within a deer park was manipulated to produce a habitat that was both suitable for the deer and also provided space for hunting. "Tree dotted lawns, tree clumps and compact woods" [11] provided "launds" (pasture)[12] over which the deer were hunted and wooded cover for the deer to avoid human contact. The landscape was intended to be visually attractive as well as functional.

Identifying former deer parks

W. G. Hoskins remarked that "the reconstruction of medieval parks and their boundaries is one of the many useful tasks awaiting the field-worker with patience and a good local knowledge".[13] Most deer parks were bounded by significant earthworks topped by a park pale, typically of cleft oak stakes.[14] These boundaries typically have a curving, rounded plan, possibly to economise on the materials and work involved in fencing[14] and ditching.

A few deer parks in areas with plentiful building stone had stone walls instead of a park pale.[14] Examples include Barnsdale in Yorkshire and Burghley on the Cambridgeshire/Lincolnshire border.[14]

Boundary earthworks have survived "in considerable numbers and a good state of preservation".[15] Even where the bank and ditch do not survive, their former course can sometimes still be traced in modern field boundaries.[16] The boundaries of early deer parks often formed parish boundaries. Where the deer park reverted to agriculture, the newly established field system was often rectilinear, clearly contrasting with the system outside the park.

Examples

- Ashdown Park Upper Wood, Oxfordshire (formerly Berkshire)

- Barnsdale, Yorkshire[14]

- Beckley Park, Beckley, Oxfordshire[17]

- Bucknell Wood, Abthorpe, Northamptonshire

- Burghley, Lincolnshire[14]

- The Chase, Kenilworth, Warwickshire[18]

- Chawton Park Wood, Medstead, Hampshire[14]

- Chetwynd Deer Park, Newport, Shropshire

- Flitteriss Park, Leicestershire

- Hatfield Broad Oak, Essex (surviving but not functioning)[1]

- Henley Park, Lower Assendon, Oxfordshire[19]

- Longnor Deer Park, Shropshire

- Moccas Deer Park, Herefordshire (surviving in use)[1]

- Silchester, Hampshire[20]

- Sutton Coldfield Deer Park (surviving but not functioning)[1]

- Windsor Great Park, Windsor, Berkshire

See also

- Chase (land)

- Royal Forest

- Red deer was the main species introduced in these deer parks.

Notes and References

- Notes

- References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 150. ISBN 0-460-04183-5.

- ↑ Muir, Richard (200). The NEW Reading the Landscape. University of Exeter Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Sykes, Naomi (2007). "Animal Bones and Animal Parks". In Liddiard, Robert. The Medieval Park: New Perspectives. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. p. 60. ISBN 9781905119165.

- ↑ Forests and Chases of England and Wales: A Glossary. St John's College, Oxford.

- ↑ Rackham, Oliver (2003). "Wood-Pasture". The Illustrated History of the Countryside. London, UK: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 63. ISBN 9780297843351.

- ↑ An example is the planting for woods for firewood and shipbuilding in John Evelyn's Sylva, or A Discourse of Forest-Trees and the Propagation of Timber

- ↑ Finch, Jonathan; Giles, Kate, eds. (2007). Estate Landscapes: Design, Improvements and Power in the Post-Medieval Landscape. Boydell and Brewer, Woodbridge and New York. p. 19-39.

- ↑ Beresford, Maurice (1998) [1957]. History on the Ground. Sutton Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 0-7509-1884-5.

- ↑ Rackham, Oliver (1997) [1975]. The History of the Countryside. Phoenix Giant Paperback. p. 125.

- ↑ Rotherham, I.D (2007) The ecology and economics of medieval deer parks. Landscape Archaeology and Ecology, 6, 86-102.

- ↑ Muir, Richard (2007). Be Your Own Landscape Detective: Investigating Where You Are. Sutton Publishing. p. 241. ISBN 0-7509-4333-5.

- ↑ Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 146. ISBN 0-460-04183-5.

- ↑ Hoskins, W.G. (1985) [1955]. The Making of the English Landscape. Penguin Books. p. 94. ISBN 0-14-007964-5.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 Rackham, Oliver (1976). Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. p. 144. ISBN 0-460-04183-5.

- ↑ Crawford, O.G.S. (1953). Archaeology in the Field. London: Phoenix House. p. 190.

- ↑ Liddiard, R. (2007). The Medieval Deer Park: New Perspectives. Windgather Press. p. 178.

- ↑ Lobel, Mary D, ed. (1957). A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 5: Bullingdon Hundred. Victoria County History. pp. 56–76.

- ↑ Salzman, L.F., ed. (1951). A History of the County of Warwick, Volume 6: Knightlow hundred. Victoria County History. pp. 132–143.

- ↑ Emery, Frank (1974). The Oxfordshire Landscape. The Making of the English Landscape. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 206. ISBN 0-340-04301-6.

- ↑ Page, W.H., ed. (1911). A History of the County of Hampshire, Volume 4. Victoria County History. pp. 51–56.