Mean curvature flow

In the field of differential geometry in mathematics, mean curvature flow is an example of a geometric flow of hypersurfaces in a Riemannian manifold (for example, smooth surfaces in 3-dimensional Euclidean space). Intuitively, a family of surfaces evolves under mean curvature flow if the normal component of the velocity of which a point on the surface moves is given by the mean curvature of the surface. For example, a round sphere evolves under mean curvature flow by shrinking inward uniformly (since the mean curvature vector of a sphere points inward). Except in special cases, the mean curvature flow develops singularities.

Under the constraint that volume enclosed is constant, this is called surface tension flow.

It is a parabolic partial differential equation, and can be interpreted as "smoothing".

Physical examples

The most familiar example of mean curvature flow is in the evolution of soap films. A similar 2 dimensional phenomenon is oil drops on the surface of water, which evolve into disks (circular boundary).

Mean curvature flow was originally proposed as a model for the formation of grain boundaries in the annealing of pure metal.

Properties

The mean curvature flow extremalizes surface area, and minimal surfaces are the critical points for the mean curvature flow; minima solve the isoperimetric problem.

For manifolds embedded in a symplectic manifold, if the surface is a Lagrangian submanifold, the mean curvature flow is of Lagrangian type, so the surface evolves within the class of Lagrangian submanifolds.

Related flows are:

- the surface tension flow

- the Lagrangian mean curvature flow

- the inverse mean curvature flow

Mean Curvature Flow of a Three Dimensional Surface

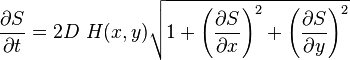

The differential equation for mean-curvature flow of a surface given by  is given by

is given by

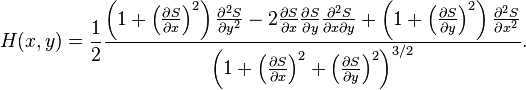

with  being a constant relating the curvature and the speed of the surface normal, and

the mean curvature being

being a constant relating the curvature and the speed of the surface normal, and

the mean curvature being

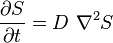

In the limits  and

and

, so that the surface is nearly planar with its normal nearly

parallel to the z axis, this reduces to a diffusion equation

, so that the surface is nearly planar with its normal nearly

parallel to the z axis, this reduces to a diffusion equation

While the conventional diffusion equation is a linear parabolic partial differential equation and does not develop singularities (when run forward in time), mean curvature flow may develop singularities because it is a nonlinear parabolic equation. In general additional constraints need to be put on a surface to prevent singularities under mean curvature flows.

References

- Ecker, Klaus. "Regularity Theory for Mean Curvature Flow", Progress in nonlinear differential equations and their applications, 75, Birkhauser, Boston, 2004.

- Mantegazza, Carlo. " Lecture Notes on Mean Curvature Flow", Progress in Mathematics, 290, Birkhauser, Basel, 2011.

- Equations 3a and 3b of C. Lu, Y. Cao, and D. Mumford. "Surface Evolution under Curvature Flows", Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, 13, pp. 65-81, 2002.