Maurice Read

Maurice Read | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batting style | Right-handed batsman (RHB) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bowling style | Right arm fast-medium (RFM) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| International information | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| National side |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Career statistics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

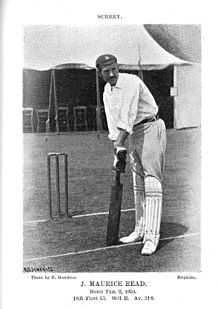

John Maurice Read (1859 – 17 February 1929 in Winchester, Hampshire) was an English professional cricketer. Wrote Harry Altham of him in that truly magisterial work, A History of Cricket, "Maurice Read had been recognised as a dashing player up to Test Match form, to say nothing of being a wonderful fielder in the country." A hard-hitting and, according to Lord Hawke, "magnificent batsman who never had pretensions to be even a moderate change bowler", Read did little trundling except in 1883, when he claimed 27 first-class wickets including his career best of 6–41 against Kent.

Read joined his local Thames Ditton Cricket Club in 1879, made his first-class debut for Surrey County Cricket Club in 1880, and played regularly for his county for fifteen years. His most productive year was 1886, when he scored 1,364 runs at an average of 34.97, including two centuries and seven fifties. He was also extremely productive in the first half of 1889, and was recognised by being named a Wisden Cricketer of the Year in 1890, but his season was affected later in the year by a bad finger injury.

Test debut and career

Born 9 February 1859 in Thames Ditton, Surrey, Read made his debut in the Oval (his home ground) Test Match against Australia in 1882, the match famous for bringing about the Ashes. According to the Manchester Guardian, Read's selection "was admittedly something of an experiment. He has played two or three lucky innings lately, but these do not make a cricketer any more than two or three swallows make a summer." A week or so prior the Test, however, Read had shared in a 158-run partnership against the tourists with fellow professional and England player Billy Barnes. Read finished on 130 and, like most of his team-mates, went into the match in good form.

In England's first innings, the local boy was cheered affectionately all the way to the middle by an avid Oval crowd. Fred Spofforth, however, soon walloped the hero three excruciating blows—one in the ribs, another on the knee and one more on the elbow. Read was compelled to hold up the game on two of these occasions to take time to convalesce, and it was, by all reports, an exceptionally valiant knock. Read finished unbeaten on nineteen, the second best score of the innings, and the masses cheered him all the way back to the pavilion just as they had cheered him from it; indeed, they it patently apparent right through this game that he was an authentic darling of the people.

There are copious examples in this match which serve to support Altham's affirmation that Read was "a wonderful fielder in the country" (i.e. outfield). He is frequently recorded in contemporary accounts of the game as chasing the ball down as fast as he could, and he certainly managed to bring to a halt plenty of potential Australian boundaries.

In the second innings, Read was one of the many victims of England captain Monkey Hornby's spectacular alteration of the batting order, promoted in front of the apparently nerveless CT Studd. When he came into view from the pavilion, Read was again cheered stridently all the way to the wicket, but, when Spofforth bowled him for a duck, the Australians were the ones, wrote Charles Pardon in Bell's Life, who "exhibited to the full their increasing delight".

This, of course, was the game which launched the legend of The Ashes after the Australians won it by seven runs.

When he came back to Australia in 1886/87, Read was flabbergasted at the pickiness of the Australian public, and he wrote of it: "If you have a bit of bad luck and make nothing two or three times, you are not of much account in Australia, and out of the team you should go, even if you have scored excellently on occasions." In England, however, it was different. "There," he reckoned, "if you are a recognised player, half a dozen successive noughts will not exclude you from a team."

Read remained a regular selection for England until 1893, being awarded that year's Oval Test (against South Africa) as a benefit. Although his batting at this level was not spectacular – he passed fifty only twice in his 29 Test innings – his fielding at third man was excellent. He also appeared for the Players against the Gentlemen on 17 occasions.

Read and Lohmann

George Lohmann, for one, preferred watching Read (and even AE Stoddart) to Arthur Shrewsbury, the man whom WG Grace placed second only to himself. Indeed, Read and Lohmann were extremely good friends, and they even shared a few personal jokes. ("Look out!" Lohmann would say to Read; "I'm going to bowl at the sticks now!"—and Read would watch with amusement as his comrade sent down all manner of strange deliveries to tempt the batsman into hitting out.)

Read was sent along to South Africa with Lohmann in 1892 to be of assistance to the great bowler in his recuperation following a ghastly (but altogether foreseeable) physical collapse as a result of overbowling. The pair sailed from Southampton on Christmas Eve, and, in March 1893, when Lohmann was healthy enough to be left on his own, Read made his homecoming for the start of the new season. (Lohmann later broke down again, however, eventually dying in South Africa.)

Incidentally, another colleague of Read's who suffered the effects of being overbowled was Tom Richardson, a Surrey and Thames Ditton team-mate. Read was one of the first to forecast what would eventually happen to this great fast bowler, conjecturing ominously about the strenuous effects that the 1897/98 tour might have on Richardson's body. He was, of course, proven correct.

Career's end

After scoring 131 to help Surrey defeat Hampshire by an innings in 1895, Read retired from first-class cricket at the age of 36 – relatively young by 19th century standards – to work on the Tichborne Park estate in Hampshire, although he continued to bat with great success in minor cricket for the Tichborne side for some years thereafter. He died at the age of 70 in Winchester after a long illness. George Giffen called him "one of the most genuine cricketers I met".

Read's uncle (by marriage) Heathfield Stephenson had a long career with Surrey, and his brother Frederick Read also played one first-class game for the county. He died 9 February 1859 in Thames Ditton, Surrey.