Matrix differential equation

A differential equation is a mathematical equation for an unknown function of one or several variables that relates the values of the function itself and of its derivatives of various orders. A matrix differential equation contains more than one function stacked into vector form with a matrix relating the functions to their derivatives.

For example, a simple matrix ordinary differential equation is

where  is an n×1 vector of functions of an underlying variable t,

is an n×1 vector of functions of an underlying variable t,  is the vector of first derivatives of these functions, and

is the vector of first derivatives of these functions, and  is an n×n matrix, of which all elements are constants.

is an n×n matrix, of which all elements are constants.

Note that by using the Cayley-Hamilton theorem and Vandermonde-type matrices, a solution may be given in a simple form.[1] Below the solution is displayed in terms of Putzer's algorithm.[2]

This differential equation has the following general solution:

where  ,

,  , ... and

, ... and  are the eigenvalues of

are the eigenvalues of  ;

;  ,

,  , ... and

, ... and  are the respective eigenvectors of

are the respective eigenvectors of  and

and  ,

,  , .... and

, .... and  are constants.

are constants.

Stability and steady state of the matrix system

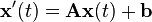

The matrix equation  with n×1 parameter vector b is stable if and only if all eigenvalues of the matrix A have a negative real part. The steady state x* to which it converges if stable is found by setting

with n×1 parameter vector b is stable if and only if all eigenvalues of the matrix A have a negative real part. The steady state x* to which it converges if stable is found by setting  , yielding

, yielding  , assuming A is invertible. Thus the original equation can be written in homogeneous form in terms of deviations from the steady state:

, assuming A is invertible. Thus the original equation can be written in homogeneous form in terms of deviations from the steady state: ![{\mathbf {x}}'(t)={\mathbf {A}}[{\mathbf {x}}(t)-{\mathbf {x}}^{*}]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/5/d/d/25dd77411059a7c9eebc3d96f5d82ffd.png) .

A different way of expressing this (closer to regular usage) is that x* is a particular solution to the in-homogenous equation, and all solutions are in the form

.

A different way of expressing this (closer to regular usage) is that x* is a particular solution to the in-homogenous equation, and all solutions are in the form  , with

, with  a solution to the homogenous equation (b=0).

a solution to the homogenous equation (b=0).

Solution in matrix form

Matrix exponentials can be used to express the solution of ![{\mathbf {x}}'(t)={\mathbf {A}}[{\mathbf {x}}(t)-{\mathbf {x}}^{*}]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/5/d/d/25dd77411059a7c9eebc3d96f5d82ffd.png)

![{\mathbf {x}}(t)={\mathbf {x}}^{*}+e^{{{\mathbf {A}}t}}[{\mathbf {x}}(0)-{\mathbf {x}}^{*}]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/0/c/c/5/0cc5022e09bf2c358d983ccea9c6cd1a.png) .

.

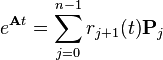

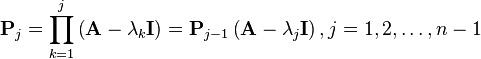

Putzer Algorithm for computing eAt

Given a matrix  with eigenvalues

with eigenvalues  then

then

Where

The equations for  are simple first order nonhomogeneous ODEs.

are simple first order nonhomogeneous ODEs.

Notice the algorithm does not require that the matrix  is diagonalizable and avoids the complexity of using Jordan canonical form when it is not needed.

is diagonalizable and avoids the complexity of using Jordan canonical form when it is not needed.

Deconstructed example of a matrix ordinary differential equation

A first-order homogeneous matrix ordinary differential equation in two functions x(t) and y(t), when taken out of matrix form, has the following form:

where  and

and  may be any arbitrary scalars.

may be any arbitrary scalars.

Higher order matrix ODE's may possess a much more complicated form.

Solving deconstructed matrix ordinary differential equations

The process of solving the above equations and finding the required functions, of this particular order and form, consists of 3 main steps. Brief descriptions of each of these steps are listed below:

- Finding the eigenvalues

- Finding the eigenvectors

- Finding the needed functions

The final, third, step in solving these sorts of ordinary differential equations is usually done by means of plugging in the values, calculated in the two previous steps into a specialized general form equation, mentioned later in this article.

Solved example of a matrix ODE

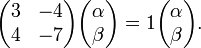

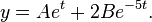

To solve the matrix ODE's according to the three steps above, using simple matrices in the process, let us find, say, function  and function

and function  , both in terms of the single underlying variable t, in the following linear differential equation of the first order:

, both in terms of the single underlying variable t, in the following linear differential equation of the first order:

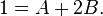

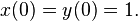

To solve this particular ordinary differential equation, at some point of the solving process, we need an initial value, a starting point. In this case, we use

First step

The first step, that has already been mentioned above, is finding the eigenvalues. The process of finding the eigenvalues is not a very difficult process. Both eigenvalues and eigenvectors are useful in numerous branches of mathematics, including higher engineering mathematics/calculations(i.e. Applied Mathematics), mechanics, physical mathematics, mathematical economics, and linear algebra.

Therefore, the process consists of the following:

-

=

=

The derivative notation x' etc. seen in one of the vectors above is known as Lagrange's notation, first introduced by Joseph Louis Lagrange. It is equivalent to the derivative notation dx/dt used in the previous equation, known as Leibniz's notation, honouring the name of Gottfried Leibniz.

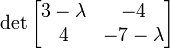

Once the coefficients of the two variables have been written in the matrix form shown above, we may start the process of evaluating the eigenvalues. To do that we are going to have to find the determinant of the matrix that is formed when an identity matrix,  , multiplied by some constant lambda, symbol λ, is subtracted from our coefficient matrix in the following way:

, multiplied by some constant lambda, symbol λ, is subtracted from our coefficient matrix in the following way:

-

.

.

Applying further simplification and basic rules of matrix addition we come up with the following:

-

.

.

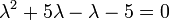

Applying the rules of finding the determinant of a single 2×2 matrix, we obtain the following elementary quadratic equation:

which may be reduced further to get a simpler version of the above:

-

.

.

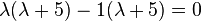

Now finding the two roots,  and

and  of the given quadratic equation by applying the factorization method we get the following:

of the given quadratic equation by applying the factorization method we get the following:

-

.

.

The values,  and

and  , that we have calculated above are the required eigenvalues. Once we find these two values, we proceed to the second step of the solution. We'll use the calculated eigenvalues later in the final solution.

In some cases, say other matrix ODE's, the eigenvalues may be complex, in which case the following step of the solving process, as well as the final form and the solution, dramatically change.

, that we have calculated above are the required eigenvalues. Once we find these two values, we proceed to the second step of the solution. We'll use the calculated eigenvalues later in the final solution.

In some cases, say other matrix ODE's, the eigenvalues may be complex, in which case the following step of the solving process, as well as the final form and the solution, dramatically change.

Second step

As it was already mentioned above, in a simple description, this step involves finding the eigenvectors by means of using the information originally given to us.

For each of the eigenvalues calculated we are going to have an individual eigenvector. For our first eigenvalue, which is  , we have the following:

, we have the following:

Simplifying the above expression by applying basic matrix multiplication rules we have:

-

.

.

All of these calculations have been done only to obtain the last expression, which in our case is  . Now taking some arbitrary value, presumably a small insignificant value, which is much easier to work with, for either

. Now taking some arbitrary value, presumably a small insignificant value, which is much easier to work with, for either  or

or  (in most cases it does not really matter), we substitute it into

(in most cases it does not really matter), we substitute it into  . Doing so produces a very simple vector, which is the required eigenvector for this particular eigenvalue. In our case, we pick

. Doing so produces a very simple vector, which is the required eigenvector for this particular eigenvalue. In our case, we pick  , which, in turn determines that

, which, in turn determines that  and, using the standard vector notation, our vector looks like this:

and, using the standard vector notation, our vector looks like this:

Performing the same operation using the second eigenvalue we calculated, which is  , we obtain our second eigenvector. The process of working out this vector is not shown, but the final result is as follows:

, we obtain our second eigenvector. The process of working out this vector is not shown, but the final result is as follows:

Once we've found both needed vectors, we start the third and last step. Don't forget that we'll substitute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors determined above into a specialized equation (shown shortly).

Third (final) step

This final step actually finds the required functions that are 'hidden' behind the derivatives given to us originally. There are two functions because our differential equations deal with two variables.

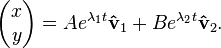

The equation, which involves all the pieces of information that we have previously found has the following form:

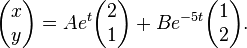

Substituting the values of eigenvalues and eigenvectors we get the following expression:

Applying further simplification rules we have:

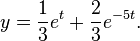

Simplifying further and writing the equations for functions  and

and  separately:

separately:

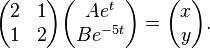

The above equations are in fact the functions that we needed to find, but they are in their general form and if we want to actually find their exact forms and solutions, now is the time to look back at the information given to us, the so-called initial value problem. At some point during solving these equations we have come across  , which plays the role of starting point for our ordinary differential equation. Now is the time to apply this condition, which lets us find the constants, A and B. As we see from the

, which plays the role of starting point for our ordinary differential equation. Now is the time to apply this condition, which lets us find the constants, A and B. As we see from the  condition, when

condition, when  , the overall equation is equal to 1. Thus we may construct the following system of linear equations:

, the overall equation is equal to 1. Thus we may construct the following system of linear equations:

Solving these equations we find that both constants A and B are equal to 1/3. Therefore if we substitute these values into the general form of these two functions we have their exact forms:

which is our final form of the two functions we were required to find.

See also

- Nonhomogeneous equations

- Matrix difference equation

- Newton's law of cooling

- Fibonacci Sequence

- Difference equations

- Wave equation

References

- ↑ H. Moya-Cessa, F. Soto-Eguibar, DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS: AN OPERATIONAL APPROACH, RINTON PRESS, New Jersey, 2011. ISBN 978-1-58949-060-4

- ↑ E. J. Putzer (1966). "Avoiding the Jordan Canonical Form in the Discussion of Linear Systems with Constant Coefficients", The American Mathematical Monthly, 73, No. 1 (1966) 2-7. , Paper on JSTOR