Mathematical joke

A mathematical joke is a form of humor which relies on aspects of mathematics or a stereotype of mathematicians to derive humor. The humor may come from a pun, or from a double meaning of a mathematical term, or from a lay person's misunderstanding of a mathematical concept. Mathematician and author John Allen Paulos in his book Mathematics and Humor described several ways that mathematics, generally considered a dry, formal activity, overlaps with humor, a loose, irreverent activity: both are forms of "intellectual play"; both have "logic, pattern, rules, structure"; and both are "economical and explicit".[1]

Some performers combine mathematics and jokes to entertain and/or teach math.[2][3][4]

Pun-based jokes

Some jokes use a mathematical term with a second non-technical meaning as the punchline of a joke.

- Q. What's purple and commutes?

- A. An Abelian grape. (A pun on Abelian group.)[5]

Occasionally multiple mathematical puns appear in the same jest:

- "When Noah sends his animals to go forth and multiply, a pair of snakes replies “We can't multiply, we're adders” — so Noah builds them a log table."[6]

This invokes three double meanings: adder (snake) vs. addition (algebraic operation); multiplication (biological reproduction) vs. multiplication (algebraic operation); log (cut tree trunk) vs. log (mathematical logarithm)[7]

.jpg)

Other jokes create a double meaning from a direct calculation involving facetious variable names, such as this retold from Gravity's Rainbow:[8]

- Person 1: What's the integral of 1/cabin with respect to cabin?

- Person 2: A log cabin.

- Person 1: No, a houseboat; you forgot to add the C![9]

The first part of this joke relies on the fact that the primitive (formed when finding the antiderivative) of the function 1/x is log(x). The second part is then based on the fact that the antiderivative is actually a class of functions, requiring the inclusion of a constant of integration, usually denoted as C—something which calculus students may forget. Thus, the indefinite integral of 1/cabin is "log(cabin) + C", or "A log cabin plus the sea", i.e., "A houseboat".

Jokes with numeral bases

- "There are only 10 types of people in the world: those who understand binary, and those who don't."

This well-known joke[10] mocks phrases that begin with "there are two types of people in the world..." and relies on an ambiguous meaning of the expression 10, which in the binary numeral system is equal to the decimal number two and in any arbitrary numeral system is equal to the number base in use.[11]

Another pun using different radices, sometimes attributed to computer scientists, asks:

The play on words lies in the similarity of the abbreviation for October/Octal and December/Decimal, and the coincidence that the two representations equal the same amount (31 Octal is  Decimal).

Decimal).

Imaginary and complex numbers

In mathematics, an imaginary number is a square root of a negative quantity, such as the constant i:

A complex number is a quantity which can be written as the sum of a real number plus an imaginary number.

While a pun has been based upon the constant's name ("complex numbers are all fun and games until someone loses an i"), most jokes treat an imaginary number as if it were a fictional entity. A telephone intercept message of "you have dialled an imaginary number, please rotate your handset ninety degrees and try again" is a typical example.[14]

The most common application of imaginary and complex numbers to physical quantities is in electrical engineering, where the imaginary component serves in alternating current calculations to represent current drawn 90° out of phase with voltage. As this imaginary power serves only to repeatedly charge and discharge reactive elements such as capacitors and inductors, it does no useful work.[15] A utility may financially penalise a large industrial client for a low power factor which requires larger electrical conductors to carry these out-of-phase currents.

A mathematical joke would describe a factory manager balking "Why should real money be paid for imaginary power?" and issuing a cheque for real money for the useful real power the factory consumes, plus a separate cheque for the square root of negative one dollars for the imaginary power the factory's owner never ordered and did not want.

Stereotypes of mathematicians

Some jokes are based on stereotypes of mathematicians tending to think in complicated, abstract terms, causing them to lose touch with the "real world". These compare mathematicians to physicists, engineers, or the "soft" sciences in a form similar to an Englishman, an Irishman and a Scotsman, showing the other scientist doing something practical, while the mathematician proposes a theoretically valid but physically nonsensical solution.

- A physicist, a biologist and a mathematician are sitting in a street café watching people entering and leaving the house on the other side of the street. First they see two people entering the house. Time passes. After a while they notice three people leaving the house. The physicist says, "The measurement wasn't accurate." The biologist says, "They must have reproduced." The mathematician says, "If one more person enters the house then it will be empty."[16]

Mathematicians are also shown as averse to making sweeping generalizations from a small amount of data, even if some form of generalization seems plausible:

- An astronomer, a physicist and a mathematician are on a train in Scotland. The astronomer looks out of the window, sees a black sheep standing in a field, and remarks, "How odd. All the sheep in Scotland are black!" "No, no, no!" says the physicist. "Only some Scottish sheep are black." The mathematician rolls his eyes at his companions' muddled thinking and says, "In Scotland, there is at least one sheep, at least one side of which appears to be black from here some of the time."[17]

A classic joke involving stereotypes is the "Dictionary of Definitions of Terms Commonly Used in Math Lectures."[18] Examples include "Trivial: If I have to show you how to do this, you're in the wrong class" and "Similarly: At least one line of the proof of this case is the same as before."

Non-mathematician's math

This category of jokes comprises those that exploit common misunderstandings of mathematics, or the expectation that most people have only a basic mathematical education, if any.

- A museum visitor was admiring a Tyrannosaurus fossil, and asked a nearby museum employee how old it was. "That skeleton's sixty-five million and three years, two months and eighteen days old," the employee replied. "How can you know it that well?" she asked. "Well, when I started working here, I asked a scientist the exact same question, and he said it was sixty-five million years old—and that was three years, two months and eighteen days ago."[19]

The joke is that the employee fails to understand the scientist's implication of the uncertainty in the age of the fossil and uses false precision.

Mock mathematics

A form of mathematical humor comes from using mathematical tools (both abstract symbols and physical objects such as calculators) in various ways which transgress their intended scope. These constructions are generally devoid of any substantial mathematical content, besides some basic arithmetic.

Mock mathematical reasoning

A set of equivocal jokes applies mathematical reasoning to situations where it is not entirely valid. Many of these are based on a combination of well-known quotes and basic logical constructs such as syllogisms:

- {|

Another set of jokes relate to the absence of mathematical reasoning, or misinterpretation of conventional notation:

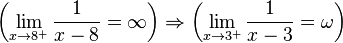

That is, the limit as x goes to 8 from above is a sideways 8 or the infinity sign, in the same way that the limit as x goes to three from above is a sideways 3 or the Greek letter omega.[21]

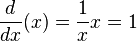

The "d"s from the first part of the equation are cancelled out and leave only one over x times x, equaling one. The first and last part of the equation are correct: the derivative of a first degree variable is 1, however the intermediate process is not mathematically sound, as "d" is not an algebraic expression but an operator.

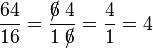

Another variant of this joke cancels out digits within the numerator and denominator of a fraction:

This produces the correct answer, but uses improper arithmetic.

Mathematical fallacies

A number of mathematical fallacies are part of mathematical humorous folklore. For example:

This appears to prove that 1 = 2, but uses incorrect algebraic manipulations (specifically, division by zero) to produce the result.[22]

See also: All horses are the same color.

Humorous numbers

Sagan (number) has been defined as "billions and billions", a metric of the number of stars in the observable universe.[23][24]

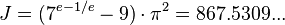

Similarly, Jenny's constant has been defined as  (sequence A182369 in OEIS), a fictional telephone number.[25]

(sequence A182369 in OEIS), a fictional telephone number.[25]

The mathematical constant 42 appears throughout the Douglas Adams trilogy The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, where it is portrayed as "the answer to life, the universe and everything".[26] The number appears as a fixed value in the TIFF image file format and its derivatives (including for example the ISO standard TIFF/EP) where the content of bytes 2-3 is defined as 42: "An arbitrary but carefully chosen number that further identifies the file as a TIFF file".[27]

Calculator spelling

Calculator spelling is the formations of words and phrases by displaying a number and turning the calculator upside down.[28] The jest may be formulated as a mathematical problem where the result, when read upside down, appears to be an identifiable phrase like "ShELL OIL" or "Esso" using seven-segment display character representations where the open-top "4" is an inverted 'h' and '5' looks like 'S'. Other letters can used as numbers too with 8 and 9 representing B and G, respectively.

Limericks

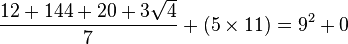

A mathematical limerick is an expression which, when read aloud, matches the form of a limerick. The following example is attributed to Leigh Mercer:[29]

This is read as follows:

- A dozen, a gross, and a score

- Plus three times the square root of four

- Divided by seven

- Plus five times eleven

- Is nine squared and not a bit more.

Doughnut and coffee mug topology joke

An oft-repeated joke is that topologists can't tell a coffee cup from a doughnut,[30] since a sufficiently pliable doughnut could be reshaped (by a homeomorphism) to the form of a cup by creating a dimple and progressively enlarging it, while shrinking the hole into a handle.

See also

- Funny numbers

- New Math (song)

- Spherical cow

- Mathematical fallacy

References

- ↑ John Allen Paulos. Mathematics and Humor.

- ↑ "Matt Parker, math stand-up comedian". Mathscareers.org.uk. 2011-08-04. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ "Dara O'Briain: School of hard sums". Comedy.co.uk. Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ Schimmrich, Steven (2011-05-17). "Dave Gorman - stand-up math comedy". Retrieved 2013-07-01.

- ↑ Weisstein, Eric W., "Abelian Group", MathWorld., citing Renteln, P. and Dundes, A. "Foolproof: A Sampling of Mathematical Folk Humor." Notices Amer. Math. Soc. 52, 24-34, 2005.

- ↑ Simanek, Donald E.; Holden, John C. (2001-10-01). Science Askew : a light-hearted look at the scientific world. ISBN 9780750307147.

- ↑ Ermida, Isabel (2008-12-10). The Language of Comic Narratives. ISBN 9783110208337.

- ↑ polyb (April 6, 2005). "Quick and Witty!". Physics Forums. Retrieved February 28, 2013.

- ↑ Bloom, Harold (2009-01-01). Thomas Pynchon. ISBN 9781438116112.

- ↑ "binary people" t-shirt

- ↑ Ritchie, Graeme (2002-06-01). The Linguistic Analysis of Jokes. ISBN 9780203406953.

- ↑ Larman, Craig (2002). Applying Uml and Patterns. ISBN 9780130925695.

- ↑ Collins, Tim (2006-08-29). Are You a Geek?. ISBN 9780440336280.

- ↑ Elizabeth Longmier (2007-05-01). In the Lab. ISBN 9781430322160. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ↑ P. P. Deo (2007-01-01). Power System Analysis. ISBN 9788184311242. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ↑ Krawcewicz, Wiesław; Rai, B. (2003-01-01). Calculus with Maple Labs : early transcendentals. ISBN 9781842650745.

- ↑ Stewart, Ian (1995). Concepts of Modern Mathematics. ISBN 9780486134956.

- ↑ Calculus Humor, Dictionary of Definitions of Terms Commonly Used in Math Lectures from Calculus humor

- ↑ Seife, Charles (2010-09-23). Proofiness. ISBN 9781101443507.

- ↑ Lawless, Andrew (2005). Plato's Sun. ISBN 9780802038098.

- ↑ Xu, Chao (2008-02-21). "A mathematical look into the limit joke". Retrieved 2008-04-19.

- ↑ Harro Heuser: Lehrbuch der Analysis - Teil 1, 6th edition, Teubner 1989, ISBN 978-3-8351-0131-9, page 51 (German).

- ↑ William Safire, ON LANGUAGE; Footprints on the Infobahn, New York Times, April 17, 1994

- ↑ Sizing up the Universe - Stars, Sand and Nucleons - Numericana

- ↑ "Jenny's Constant". Wolfram MathWorld. 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2013-06-19.

- ↑ Gill, Peter (2011-02-03). "42: Douglas Adams' Amazingly Accurate Answer to Life the Universe and Everything". London: Guardian. Retrieved 2011-04-03.

- ↑ Aldus/Microsoft (1999-08-09). "1) Structure". TIFF. Revision 5.0. Aldus Corporation and Microsoft Corporation. Retrieved 2009-06-29. "The number 42 was chosen for its deep philosophical significance."

- ↑ Bolt, Brian (1984-09-27). The Amazing Mathematical Amusement Arcade. ISBN 9780521269803.

- ↑ "Math Mayhem". Lhup.edu. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

- ↑ West, Beverly H (1995-03-30). Differential Equations: A Dynamical Systems Approach : Higher-Dimensional Systems. ISBN 9780387943770. Retrieved 2011-06-29.

External links

- A Sampling of Mathematical Folk Humor

- Mathematical Humor — from Mathworld

- Paul Renteln and Alan Dundes (2004-12-08). "Foolproof: A Sampling of Mathematical Folk Humor" (PDF). Notices of the AMS 52 (1).