Mashing

In brewing and distilling, mashing is the process of combining a mix of milled grain (typically malted barley with supplementary grains such as corn, sorghum, rye or wheat), known as the "grain bill", and water, known as "liquor", and heating this mixture. Mashing allows the enzymes in the malt to break down the starch in the grain into sugars, typically maltose to create a malty liquid called wort.[1] There are two main methods—infusion mashing, in which the grains are heated in one vessel; and decoction mashing, in which a proportion of the grains are boiled and then returned to the mash, raising the temperature.[2] Mashing involves pauses at certain temperatures (notably 45 °C, 62 °C and 73 °C) [113°F, 144°F, and 163°F], and takes place in a "mash tun"—an insulated brewing vessel with a false bottom.[3][4][5] The end product of mashing is called a "mash".[<span title="Request pertains to the single sentence, 'The end product of mashing is called a "mash"'. (November 2012)">citation needed]

Infusion mashing

Most breweries use infusion mashing, in which the mash is heated directly to go from rest temperature to rest temperature. Some infusion mashes achieve temperature changes by adding hot water, and there are also breweries that do single-step infusion, performing only one rest before lautering.

Decoction mashing

Decoction mashing is where a proportion of the grains are boiled and then returned to the mash, raising the temperature. The boiling extracts more starch from the grain by breaking down the cell walls of the grain. It can be classified into one-, two-, and three-step decoctions, depending on how many times part of the mash is drawn off to be boiled.[6] It is a traditional method, and is common in German and Central European breweries.[7][8] It was used out of necessity before the invention of thermometers allowed simpler step mashing. But the practice continues for many traditional beers because of the unique malty flavor it lends to the beer; boiling part of the grain results in Maillard reactions, which create melanoidins that lead to rich, malty flavours.[9]

Mash tun

In large breweries, in which optimal utilization of the brewery equipment is economically necessary, there is at least one dedicated vessel for mashing. In decoction processes, there must be at least two. The vessel has a good stirring mechanism, a mash rake, to keep the temperature of the mash uniform, and a heating device that is efficient, but will not scorch the malt (often steam), and should be insulated to maintain rest temperatures for up to one hour. A spray ball for clean-in-place (CIP) operation should also be included for periodic deep cleaning. Sanitation is not a major concern before wort boiling, so a rinse-down should be all that is necessary between batches.

Smaller breweries will often use a boil kettle or a lauter tun for mashing. The latter case either limits the brewer to single-step infusion mashing or leaves the brewer with a lauter tun that is not completely appropriate for the lautering process.

Ingredient selection

Each particular ingredient has its own flavor that contributes to the final character of the beverage. In addition, different ingredients carry other characteristics, not directly relating to the flavor, which may dictate some of the choices made in brewing: nitrogen content, diastatic power, color, modification, and conversion.

Nitrogen content

The nitrogen content of a grain refers to the mass fraction of the grain that is made up of protein, and is usually expressed as a percentage; this fraction is further refined by distinguishing what fraction of the protein is water-soluble, also usually expressed as a percentage; 40% is typical for most beermaking grains. Generally, brewers favor lower-nitrogen grains, while distillers favor high-nitrogen grains.

In most beermaking, an average nitrogen content in the grains of at most 10% is sought; higher protein content, especially the presence of high-mass proteins, causes "chill haze", a cloudy visual quality to the beer. However, this is mostly a cosmetic desire dating from the mass production of glassware for presenting serving beverages; traditional styles such as sahti, saison, and bière de garde, as well as several Belgian styles, make no special effort to create a clear product. The quantity of high-mass proteins can be reduced during the mash by making use of a protease rest.

In Britain, preferred brewers' grains are often obtained from winter harvests and grown in low-nitrogen soil; in central Europe, no special changes are made for the grain-growing conditions and multi-step decoction mashing is favored instead.

Distillers, by contrast, are not as constrained by the amount of protein in their mash as the non-volatile nature of proteins means that none will be included in the final distilled product. Therefore, distillers seek out higher-nitrogen grains in order to ensure a more efficiently-made product; higher-protein grains generally have more diastatic power.

Diastatic power

The diastatic power (DP), also called the "diastatic activity" or "enzymatic power", of a grain in general refers only to malts, grains that have begun to germinate; the act of germination includes the production of a number of enzymes such as amylase that convert starch into sugar; thereby, sugars can be extracted from the barley's own starches simply by soaking the grain in water at a controlled temperature: this is mashing. Other enzymes break long proteins into short ones and accomplish other important tasks.

In general, the hotter a grain is kilned, the less its diastatic activity; as a consequence, only lightly colored grains can be used as base malts, with Munich malt being the darkest base malt generally available.

Diastatic activity can also be provided by diastatic malt extract or by inclusion of separately-prepared brewing enzymes.

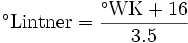

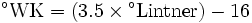

Diastatic power for a grain is measured in degrees Lintner (°Lintner or °L, although the latter can conflict with the symbol °L for Lovibond color); or in Europe by Windisch-Kolbach units (°WK). The two measures are related by

.

.

A malt with enough power to self-convert has a diastatic power near 35 °Lintner (94 °WK). Until recently the most active, so-called "hottest" malts currently available, American six-row pale barley malts, have a diastatic power of up to 160 °Lintner (544 °WK). Wheat malts have begun to appear on the market with diastatic power of up to 200 °Lintner. Although with the huskless wheat being somewhat difficult to work with, this is usually used in conjunction with barley, or as an addition to add high diastatic power to a mash.

Color

In brewing, the color of a grain or product is evaluated by the Standard Reference Method (SRM), Lovibond (°L), American Society of Brewing Chemists (ASBC) or European Brewery Convention (EBC) standards. While SRM and ASBC originate in North America and EBC in Europe, all three systems can be found in use throughout the world; degrees Lovibond has fallen out of industry use but has remained in use in homebrewing circles as the easiest to implement without a spectrophotometer. The darkness of grains range from as light as 3 SRM/5 EBC for Pilsener malt to as dark as 700 SRM/1600 EBC for black malt and roasted barley.

Modification

The quality of starches in a grain is variable with the strain of grain used and its growing conditions. "Modification" refers specifically to the extent to which starch molecules in the grain consist of simple chains of starch molecules versus branched chains; a fully modified grain contains only simple-chain starch molecules. A grain that is not fully modified requires mashing in multiple steps rather than at simply one temperature as the starches must be de-branched before amylase can work on them. One indicator of the degree of modification of a grain is that grain's Nitrogen ratio; that is, the amount of soluble Nitrogen (or protein) in a grain vs. the total amount of Nitrogen(or protein). This number is also referred to as the "Kolbach Index" and a malt with a Kolbach index between 36% and 42% is considered a malt that is highly modified and suitable for single infusion mashing. Maltsters use the length of the acrospire vs. the length of the grain to determine when the appropriate degree of modification has been reached before drying or kilning.

Conversion

Conversion is the extent to which starches in the grain have been enzymatically broken down into sugars. A caramel or crystal malt is fully converted before it goes into the mash; most malted grains have little conversion; unmalted grains, meanwhile, have little or no conversion. Unconverted starch becomes sugar during the last steps of mashing, through the action of alpha and beta amylases.

Grain milling

The grain used for making beer must first be milled. Milling increases the surface area of the grain, making the starch more accessible, and separates the seed from the husk. Care must be taken when milling to ensure that the starch reserves are sufficiently milled without damaging the husk and providing coarse enough grits that a good filter bed can be formed during lautering.

Grains are typically dry-milled. Dry mills come in four varieties: two-, four-, five-, and six-roller mills. Hammer mills, which produce a very fine mash, are often used when mash filters are going to be employed in the Lautering process because the grain does not have to form its own filterbed. In modern plants, the grain is often conditioned with water before it is milled to make the husk more pliable, thus reducing breakage and improving lauter speed.

Two-roller mills Two-roller mills are the simplest variety, in which the grain is crushed between two rollers before it continues on to the mash tun. The spacing between these two rollers can be adjusted by the operator. Thinner spacing usually leads to better extraction, but breaks more husk and leads to a longer lauter.

Four-roller mills Four-roller mills have two sets of rollers. The grain first goes through rollers with a rather wide gap, which separates the seed from the husk without much damage to the husk, but leaves large grits. Flour is sieved out of the cracked grain, and then the coarse grist and husks are sent through the second set of rollers, which further crush the grist without damaging the crusts. There are three-roller mills, in which one of the rollers is used twice, but they are not recognized by the German brewing industry.

Five- and Six-roller mills Six-roller mills have three sets of rollers. The first roller crushes the whole kernel, and its output is divided three ways: Flour immediately is sent out the mill, grits without a husk proceed to the last roller, and husk, possibly still containing parts of the seed, go to the second set of rollers. From the second roller flour is directly output, as are husks and any possible seed still in them, and the husk-free grits are channeled into the last roller. Five-roller mills are six-roller mills in which one of the rollers performs double-duty.

Mashing-in

Mixing of the strike water, water used for mashing in, and milled grist must be done in a such a way as to minimize clumping and oxygen uptake. This was traditionally done by first adding water to the mash vessel, and then introducing the grist from the top of the vessel in a thin stream. This has led to a lot of oxygen absorption, and loss of flour dust to the surrounding air. A premasher, which mixes the grist with mash-in temperature water while it is still in the delivery tube, reduces oxygen uptake and prevents dust from being lost.

Mashing in (sometimes called "doughing-in") is typically done between 35 and 45 °C (95 and 113 °F), but, for single-step infusion mashes, mashing in must be done between 62–67 °C (144–153 °F) for amylases to break down the grain's starch into sugars. The weight-to-weight ratio of strike water and grain varies from 1⁄2 for dark beers in single-step infusions to 1⁄4 or even 1⁄5, ratios more suitable for light-colored beers and decoction mashing, where much mash water is boiled off.

Enzymatic rests

| Temp °C | Temp °F | Enzyme | Breaks down |

|---|---|---|---|

| 40-45 °C | 104.0-113.0 °F | β-Glucanase | β-Glucan |

| 50-54 °C | 122.0-129.2 °F | Protease | Protein |

| 62-67 °C | 143.6-152.6 °F | β-Amylase | Starch |

| 71-72 °C | 159.8-161.6 °F | α-Amylase | Starch |

In step-infusion and decoction mashing, the mash is heated to different temperatures at which specific enzymes work optimally. The table at right shows the optimal temperature ranges for the enzymes brewers pay the most attention to and what material those enzymes break down. There is some contention in the brewing industry as to just what the optimal temperature is for these enzymes, as it is often very dependent on the pH of the mash, and its thickness. A thicker mash acts as a buffer for the enzymes. Once a step is passed, the enzymes active in that step are denatured by the increasing heat and become permanently inactive. The time spent transitioning between rests is preferably as short as possible; however, if the temperature is raised more than 1 °C per minute, enzymes may be prematurely denatured in the transition layer near heating elements.

β-Glucanase rest

β-glucan is a general term for polysaccharides, such as cellulose, made up of chains of glucose molecules connected by beta glycosidic bonds, as opposed to alpha glycosidic bonds in starch. These are a major constituent of the cell wall of plants, and make up a large part of the bran in grains. A β-glucanase rest done at 40 °C (104 °F) is practiced in order to break down cell walls and make starches more available, thus raising the extraction efficiency. Should the brewer let this rest go on too long, it is possible that a large amount of β-glucan will dissolve into the mash, which can lead to a stuck mash on brew day, and cause filtration problems later in beer production.

Protease rest

Protein degradation via a proteolytic rest plays many roles: production of free-amino nitrogen (FAN) for yeast nutrition, freeing of small proteins from larger proteins for foam stability in the finished product, and reduction of haze-causing proteins for easier filtration and increased beer clarity. In all-malt beers, the malt already provides enough protein for good head retention, and the brewer needs to worry more about more FAN being produced than the yeast can metabolize, leading to off flavors. The haze causing proteins are also more prevalent in all-malt beers, and the brewer must strike a balance between breaking down these proteins, and limiting FAN production.

Amylase rests

The amylase rests are responsible for the production of free fermentable and nonfermentable sugar from starch in a mash.

Starch is an enormous molecule made up of branching chains of glucose molecules. β-amylase breaks down these chains from the end molecules forming links of two glucose molecules, i.e. maltose. β-amylase cannot break down the branch points, although some help is found here through low α-amylase activity and enzymes such as limit dextrinase. The maltose will be the yeast's main food source during fermentation. During this rest starches also cluster together forming visible bodies in the mash. This clustering eases the lautering process.

The α-amylase rest is also known as the saccharification rest, because during this rest the α-amylase breaks down the starches from the inside, and starts cutting off links of glucose one to four glucose molecules in length. The longer glucose chains, sometimes called dextrins or maltodextrins, along with the remaining branched chains, give body and fullness to the beer.

Because of the closeness in temperatures of peak activity of α-amylase and β-amylase, the two rests are often performed at once, with the time and temperature of the rest determining the ratio of fermentable to nonfermentable sugars in the wort and hence the final sweetness of the fermented drink; a hotter rest gives a fuller-bodied, sweeter beer as α-amylase produces more unfermentable sugars. 66 °C (151 °F) is a typical rest temperature for a pale ale or German pilsener, while Bohemian pilsener and mild ale are rested more typically at 67–68 °C (153–154 °F).

Decoction "rests"

In decoction mashing, part of the mash is taken out of the mash tun and placed in a cooker, where it is boiled for a period of time. This caramelizes some of the sugars, giving the beer a deeper flavor and color, and frees more starches from the grain, making for a more efficient extraction from the grains. The portion drawn off for decoction is calculated so that the next rest temperature is reached by simply putting the boiled portion back into the mash tun. Before drawing off for decoction, the mash is allowed to settle a bit, and the thicker part is typically taken out for decoction, as the enzymes have dissolved in the liquid, and the starches to be freed are in the grains, not the liquid. This thick mash is then boiled for around 15 minutes, and returned to the mash tun.

The mash cooker used in decoction should not be allowed to scorch the mash, but maintaining a uniform temperature in the mash is not a priority. To prevent a scorching of the grains, the brewer must continuously stir the decoction and apply a slow heating.

A decoction mash brings out a higher malt profile from the grains and is typically used in Bocks or Doppelbock-style beers.

Mash-out

After the enzyme rests, the mash is raised to its mash-out temperature. This frees up about 2% more starch, and makes the mash less viscous, allowing the lauter to process faster. Although mash temperature and viscosity are roughly inversely proportional, the ability of brewers and distillers to use this relationship is constrained by the fact that α-Amylase quickly denatures above 78 °C (172.4 °F). Any starches extracted once the mash is brought above this temperature cannot be broken down, and will cause a starch haze in the finished product, or in larger quantities an unpleasantly harsh flavor can develop. Therefore, the mash-out temperature rarely exceeds 78 °C (172.4 °F).

If the lauter tun is a separate vessel from the mash tun, the mash is transferred to the lauter tun at this time. If the brewery has a combination mash-lauter tun, the agitator is stopped after mash-out temperature is reached and the mash has mixed enough to ensure a uniform temperature.

See also

- Grain bill

- Wort (brewing)

- Sour mash

References

- ↑ Audrey Ensminger, Foods & nutrition encyclopedia, Volume 1, page 188. CRC Press, 1994, ISBN 0849389801. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ Dan Rabin, Carl Forget, The dictionary of beer and brewing, page 180. Taylor & Francis, 1998, ISBN 1579580785. Retrieved 2010-02-20.

- ↑ "Abdijbieren. Geestrijk erfgoed" by Jef Van den Steen

- ↑ Bier brouwen

- ↑ What is mashing?

- ↑ Malting and Brewing Science: Volume I Malt and Sweet Wort, D. E. Briggs, James Shanks Hough, R. Stevens, Tom W. Young, Springer (1981), ISBN 0-412-16580-5

- ↑ Malts and malting - Google Books. books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ Malting and Brewing Science: Malt ... - Google Books. books.google.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-07-09.

- ↑ Decoction Mashing brewery.org

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mash. |