Mary Augusta Ward

| Mary Augusta Ward | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Mary Augusta Arnold 11 June 1851 Hobart, Tasmania, Australia |

| Died |

24 March 1920 (aged 68) London, England |

| Pen name | Mrs. Humphry Ward |

| Nationality | British |

| Spouse(s) | Thomas Humphry Ward |

| Children | Arnold Ward |

| Relative(s) | Tom Arnold (father) |

Mary Augusta Ward née Arnold; (11 June 1851 – 24 March 1920), was a British novelist who wrote under her married name as Mrs Humphry Ward.

Early life

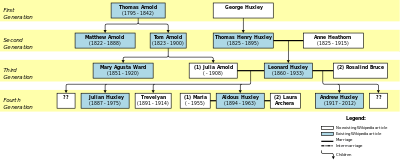

Mary Augusta Arnold was born in Hobart, Tasmania, Australia, into a prominent intellectual family of writers and educationalists. Mary was the daughter of Tom Arnold, a professor of literature, and Julia Sorrell. Her uncle was the poet Matthew Arnold and her grandfather Thomas Arnold, the famous headmaster of Rugby School. Her sister Julia married Leonard Huxley, the son of Thomas Huxley, and their sons were Julian and Aldous Huxley. The Arnolds and the Huxleys were an important influence on British intellectual life.

Mary's father Tom Arnold was appointed inspector of schools in Van Diemen's Land (now Tasmania) and commenced his role on 15 January 1850.[1] Tom Arnold was received into the Roman Catholic Church on 12 January 1856, which made him so unpopular in his job (and with his wife) that he resigned and left for England with his family in July 1856.[1] Mary Arnold had her fifth birthday the month before they left, and had no further connection with Tasmania. Tom Arnold was ratified as chair of English literature at the contemplated Catholic university, Dublin, after some delay. Mary spent much of her time with her grandmother. She was educated at various boarding schools (from ages 11 to 15, in Shifnal, Shropshire[2]) and at 16 returned to live with her parents at Oxford, where her father had a lecturership in history. Her schooldays formed the basis for one of her later novels, Marcella (1894).[3]

On 6 April 1872, not yet 21 years old, Mary married Humphry Ward, a fellow and tutor of Brasenose College, and also a writer and editor. For the next nine years she continued to live at Oxford, at 17 Bradmore Road, where she is commemorated by a blue plaque.[4] She had by now made herself familiar with French, German, Italian, Latin and Greek. She was developing an interest in social and educational service and making tentative efforts at literature. She added Spanish to her languages, and in 1877 undertook the writing of a large number of the lives of early Spanish ecclesiastics for the Dictionary of Christian Biography edited by Dr William Smith and Dr. Henry Wace.[5] Her translation of Amiel's Journal appeared in 1887.

Career

)_by_Julian_Russell_Story.jpg)

Mary Augusta Ward began her career writing articles for Macmillan's Magazine[5] while working on a book for children that was published in 1881 under the title Milly and Olly. This was followed in 1884 by a more ambitious, though slight, study of modern life, Miss Bretherton, the story of an actress.[5] Ward's novels contained strong religious subject matter relevant to Victorian values she herself practised. Her popularity spread beyond Great Britain to the United States. Her book Lady Rose's Daughter was the best-selling novel in the United States in 1903, as was The Marriage of William Ashe in 1905. Ward's most popular novel by far was the religious "novel with a purpose" Robert Elsmere, which portrayed the emotional conflict between the young pastor Elsmere and his wife, whose over-narrow orthodoxy brings her religious faith and their mutual love to a terrible impasse; but it was the detailed discussion of the "higher criticism" of the day, and its influence on Christian belief, rather than its power as a piece of dramatic fiction, that gave the book its exceptional vogue. It started, as no academic work could have done, a popular discussion on historic and essential Christianity.[5]

Ward helped establish an organisation for working and teaching among the poor. She also worked as an educator in the residential settlement movements she founded. Mary Ward's declared aim was "equalisation" in society, and she established educational settlements first at Marchmont Hall and later at Tavistock Place in Bloomsbury. This was originally called the Passmore Edwards Settlement, after its benefactor John Passmore Edwards, but after Ward's death it became the Mary Ward Settlement. It is now known as the Mary Ward Centre and continues as an adult education college; affiliated with it is the Mary Ward Legal Centre.

She was also a significant campaigner against women getting the vote. In the summer of 1908 she was approached by George Nathaniel Curzon and William Cremer, who asked her to be the founding president of the Women's National Anti-Suffrage League. Ward took on the job, creating and editing the Anti-Suffrage Review. She published a large number of articles on the subject, while two of her novels, The Testing of Diana Mallory and Delia Blanchflower, were used as platforms to criticise the suffragettes. In a 1909 article in The Times, Ward wrote that constitutional, legal, financial, military, and international problems were problems only men could solve. However, she came to promote the idea of women having a voice in local government and other rights that the men's anti-suffrage movement would not tolerate.

During World War I, Ward was asked by United States President Theodore Roosevelt to write a series of articles to explain to Americans what was happening in Britain. Her work involved visiting the trenches on the Western Front, and resulted in three books, England's Effort - Six Letters to an American Friend (1916), Towards the Goal (1917), and Fields of Victory (1919).[3]

Death

Mary Augusta Ward died in London, England, and was interred at Aldbury in Hertfordshire, near her beloved country home Stocks.

Foundations, organisations and settlements

- Evening Play Centre Committee

- Mary Ward Centre, formerly the Passmore Edwards Settlement

- Women's National Anti-Suffrage League

Associated activists in social change

- Dame Grace Kimmins

Bibliography

|

|

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: |

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Howell, P.A. (1966). "Arnold, Thomas (1823–1900)". Australian Dictionary of Biography 1. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

- ↑ Dickins, Gordon (1987). An Illustrated Literary Guide to Shropshire. Shropshire Libraries. pp. 74, 109. ISBN 0-903802-37-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Dickins, Gordon (1987). An Illustrated Literary Guide to Shropshire. p. 74.

- ↑ http://www.oxfordshireblueplaques.org.uk/plaques/ward.html

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Encyclopædia Britannica, Eleventh Edition

- ↑ "WARD, Mrs. Humphry (Mary Augusta)". Who's Who, 59: p. 1835. 1907.

- ↑ Whitaker, Joseph (1906). "Agatha". Almanack, 1906. London. p. 390.

References

- Serle, Percival (1949). "Ward, Mary Augusta". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Retrieved 1 March 2010.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ward, Mary Augusta". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ward, Mary Augusta". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

External links

| Library resources about Mary Augusta Ward |

| By Mary Augusta Ward |

|---|

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Mary Augusta Ward |

- Ward at the Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography

- Works by Mary Augusta Ward at Project Gutenberg

- Mary Augusta Ward at The Victorian Web

- Works by Ward at The Victorian Women Writers Project

- Mary Ward Centre

- Archival material relating to Mary Augusta Ward listed at the UK National Archives

|