Marvão

| Marvão | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

| |||

| |||

| Coordinates: 39°23′39″N 7°22′36″W / 39.39417°N 7.37667°WCoordinates: 39°23′39″N 7°22′36″W / 39.39417°N 7.37667°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Region | Alentejo Region | ||

| Subregion | Alto Alentejo Subregion | ||

| District/A.R. | Portalegre | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Vitor Frutuoso (PSD) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 154.9 km2 (59.8 sq mi) | ||

| Population | |||

| • Total | 3,739 | ||

| • Density | 24/km2 (60/sq mi) | ||

| Parishes (no.) | 4 | ||

| Municipal holiday |

September 8 | ||

| Website | http://www.cm-marvao.pt | ||

Marvão (Portuguese pronunciation: [mɐɾˈvɐ̃w]) is a municipality in Portugal with a total area of 154.9 square kilometres (59.8 sq mi) and a total population of 3,739 inhabitants. The municipality is composed of 4 parishes, and is located in Portalegre District. The present Mayor is Vitor Martins Frutuoso, elected by the Social Democratic Party. The municipal holiday is September 8.

Parishes

- Beirã

- Santa Maria de Marvão

- Santo António das Areias

- São Salvador da Aramenha

History

Commanding spectacular views across the Tagus basin and Serra de Estrela to the north, the fortified rock of Marvão has been a site of significant strategic importance since the earliest human settlements. Today lying on the 'raia' that divides Portugal and Spain, Marvão has consistently stood on a frontier zone between peoples: Celtici, Vettones and Lusitani (4th-2nd century BCE); Lusitanians and the Romans of Hispania Ulterior (2nd-1st century BCE); migratory Suevi, Alans, Vandals and Visigoths (5th-7th century CE); conquering moors and Visigoths (8th century); muwallad rebels and the Cordoban emirate (9th-10th century); Portuguese nation-builders and Moors (12th-13th century); Templars and Hospitallers (12th-14th century); Portuguese and Castilians (12th century-present day); Liberals and Absolutists (19th century); the fascist regimes of Salazar and Franco (20th century).

Marvão's natural assets have contributed to the 'uniqueness' of this remote village as perceived by visitors today: (i) as nigh-impregnable 'eagle's nest' fortress - perched high on a granite crag, and bordered on the south and west by the Sever river; (ii) as vital lookout-point towards the Alcántara Bridge (70 km (43 mi) away), a wide stretch of the Tagus basin and the Serra de Estrela; (iii) as a gateway to Portugal from Spain via the Porta da Espada ('Sword Gate') mountain pass of the Serra de São Mamede. These assets have ensured its status as the 'Mui Nobre e Sempre Leal Vila de Marvão' (Very Noble and Ever-Loyal Town) into the present day.

Prehistory

Pre-Roman era: Lusitani and Celtici

So in the three centuries prior to Roman conquest (3rd–1st century BCE), Marvão stood at a junction of the Celtici, Lusitani, and Vettones tribes, and its dominant strategic position offered line-of-sight long into the territories of all three tribes. A locally found head of a pig-like sculpture from the Verraco (Portuguese: berrão) culture of the Vettones is displayed in Marvão's museum.

Given their strategic location, the Serra de São Mamede and Spain's Sierra de San Pedro – in particular the dominant escarpments of Marvão on the northernmost tip and Alburquerque on the southernmost tip - are likely to have played a role in conflicts between Celtiberians and Romans. While Marvão lies north of the territories of Carthaginian Iberia – which by 218 BCE reached across Southern Iberia up to the river Guadiana), the area is likely to have been crossed during the 230s and 220–218 BCE during Carthaginian slave-raiding and mercenary-recruitment campaigns focused on the Tagus valley (e.g. Hamilcar Barca's Tagus encampment at Cartaxo) and along what later became Ruta de la Plata: Iberian manpower was to play a role in the Punic Wars.

In the 2nd century BCE, Roman might asserted itself following the Punic Wars, yet progress was slow in these border regions. A series of bloody revolts and wars (195–135 BCE) pitted the Lusitanians and Vettones - most notably under the guerrilla fighter and hero Viriatus – against the expansionist Roman colonisers of Hispania Ulterior. While nominally the area was under Roman control from the early 130s BCE, for a century an unstable war zone spread from the Serra de Estrela-Tagus basin (seen from Marvão) and the Extremaduran plains between Alburquerque and the Sierra de Aracena.

Some speculation has focused on whether 'choças', the traditional circular-floorplan barns with broom-thatched roofs – found throughout Marvão, most dating from the post-medieval period - are a vernacular survivor from these Celtic times. The 'choças' of Marvão follow the rudimentary pattern of roundhouses found throughout Celtic settlements in Europe. Similarly, a number of corbelled circular drystone shelters, with a false cupola (Portuguese:chafurdaõ) in Marvão reflect similar Iron Age structures across Southern Europe (e.g. the Spanish bombo and Croatian trim) associated with the terracing and clearance of rocky land for farming. The Vettones culture was renowned for its cattle-rearing and Verraco (Portuguese: berrão) pig-like sculptures: porco preto rearing remains dominant in local agriculture and cuisine.

The Roman era: Ammaia

In Marvão, gradual consolidation of Roman power led to the establishment of a substantial Roman town in the 1st century CE: Ammaia.[9] Occupying up to 25 hectares, and with a population exceeding modern-day Marvão (5000-6000 inhabitants), Ammaia occupied the site of the present-day parish of São Salvador da Aramenha. The town flourished between the 1st century BCE and the collapse of the Roman empire in the 5th century CE.[10]

Ammaia's location on the river Sever was a waypoint on west-east trading routes, linking towns such as Scallabis (Santarém), Eboracum (Évora), Olisipo (Lisbon) and Miróbriga (Santiago de Cacém) to the provincial capital Emerita Augusta (present-day Mérida) via Norba Caesarina (Cáceres). The mountain of Marvão would also have served as a watchtower providing line-of-sight to the vitally-important Roman bridge at Alcántara. Local agricultural production (olives, wine, figs, cattle) was supplemented by horse-breeding, pottery, and mining activity - notably rock crystal and quartz from veins on the Marvão mountain, together with open cast gold mining on the Tagus to the north.[11] Roman Ammaia saw the development of improved irrigation and terracing across the Marvão mountain. Chestnut cultivation - replacing the local dominance of oak - is likely to have been introduced at this time. Much of the terracing and ancient watercourses on the Marvão mountain date from this era.

Limited excavations at Ammaia in the past two decades - albeit covering a mere 3,000 m2 (32,292 sq ft) of the town's area - have revealed a successful, expanding provincial town that included running water, a forum, baths, a bridge over the river Sever (near today's 'Ponte Velha'), and monumental gates (one gate was removed to Castelo de Vide in the 18th century, yet sadly dynamited in 1890). The Alto Alentejo region, meanwhile, was criss-crossed with efficient Roman roads, providing wider links to the Empire. Fine wares found at Ammaia suggest that the local Ammaia nobility had access to luxury glassware and jewellery, while archaeology has revealed that marble for the forum was imported from across the Empire. The high quality, for example, of the 'Mosaico das Musas' - from a Roman villa in nearby Monforte (4th century BCE) - points to the abundant riches to be made as an Alentejo landowner in the Roman era. Sadly, many artifacts from Ammaia - in particular a series of marble sculptures - were removed during the 19th and 20th centuries, notably by the Anglo-Portuguese Robinson family. These items are now in collections such as those of the British Museum.[12]

The post-Roman era: decline of Ammaia, Alans, Suevi and the Visigoths

During the 5th-7th century, the invasion of Roman Iberia by a succession of tribes from Central Europe - the Vandals, Suevi, Alans and Visigoths - left an indelible mark on Marvão and Lusitania as a whole. Hispano-Roman urban centres across Iberia suffered two centuries of instability, violence and depopulation, and many towns fell into ruin. Ammaia was no exception.

Historic documentation for the invasion of towns around Mérida province is poor, yet these were clearly difficult times for Ammaia. It is likely that the years 409-411 were catastrophic. Following the invasion of Spain in September or October 409, invading tribes used extreme violence in conquering the cities of Roman Spain. A quotation from Hydatius - albeit about Spain in general - gives an idea of the last days of Ammaia: 'As the barbarians ran wild through Spain with the evil of pestilence raging as well, the tyrannical tax collector seized the wealth and goods stored in the cities and the soldiers devoured them. A famine ran riot, so dire that driven by hunger humans devoured human flesh: mothers too feasted on the bodies of their own children whom they had killed and cooked themselves... And thus with the four plagues of sword, famine, pestilence and wild beasts raging everywhere, the annunciation foretold by the Lord through his prophets was fulfilled'.

In Marvão, the once-thriving Roman town of Ammaia fell into ruin. Its 4th-century population of 6,000 people had represented about 1% of the Iberian population (6 million). Yet it would be described merely as 'ruins' in the 8th century CE. Why the decay? Fortified rural farmsteads and hilltop fortresses provided safe havens in times of conflict. It is likely that any Roman watchtower fortification on Marvão's rock would have been extended in this period. Ammaia's role as horse station and key link in the road network declined as east-west trade plummeted. The Visigothic capital was in Toledo, on the river Tagus: this favoured river transport of goods to-and-from Santarem and Lisbon. Ammaia's decline in this period can be contrasted with the buoyant Visigothic development of Idanha-a-Velha on the north of the Tagus.

The borders between tribes were in continuous flux, with Suevi (strongholds in Galicia and Braga) fighting the Alans and Visigoths. Five centuries of incumbent Hispano-Roman urban culture gave way to interaction with the nomadic, pastoralist lifetyles of tribes such as the Alans (dominant in much of former Lusitania after the Battle of Mérida). Roman imperial law-and-order succumbed to the looser hierarchies - based on blood and tribal allegiances - of the invaders from the north. War, slave-raids, banditry, religious intolerance, apartheid - the Visigoths applied a 'no mixing' policy for much of their rule - all led to economic decline across Iberia.

While little can be seen today in Marvão of this period, tradition states that the large herding dogs of Iberia were introduced by the Alans: (Portuguese mastiffs can be seen guarding livestock in fields around Marvão, while the bulky Alano Espãnol was used in Spanish bullfights).

The Islamic era: invasion, the Ibn Marwán rebellion, the Badajoz taifa, Christian reconquest

Invasion: Land of the Berbers and Western Thugūr

The Muslim invasion of al-Andalus in 711 is likely to have reached the area around Marvão during the Spring campaign of Abd al-Aziz in 714 CE (when Coimbra and Santarém were also captured). The invasion would herald five centuries of Islamic rule, until Marvão was captured by the Portuguese nation-builder Afonso I of Portugal in the 1160s.

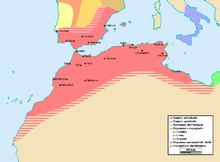

It is believed that during unstable decades from 711-756 in al-Andalus, power struggles between Arab and Berber factions, together with newly converted Visigoths (muwalladi), led to a division of territory: richer agricultural lands in the Guadalquivir basin fell under Arab control, and mountainous areas such as the Serra de São Mamede were generally held by Berber clansmen. Arab sources refer to the area north of the Guadiana as Bi:lad al-Barbar or Lands of the Berbers.[13] Following the chaotic decades of invasion, by the later 8th century CE Marvão would have formed part of the Western thughūr ('march' i.e. buffer area or boundary zone) ruled by a marcher lord, or ka'id from the old Lusitanian capital of Mérida.[14] One of three marches, this was known as the Lower March (al-Tagr al-Adna) or Distant March (al-Tagr al-Aqsa). The Lower March - the territorial division known as Xenxir - gained a reputation for the rebelliousness and reluctance of its inhabitants to comply with governance from Cordoba, with Mérida being a seething hive of discontent, revolution and tax-refuseniks.[15] Feuds between clansmen covered a wide area across the former Lusitania province, reaching Christian lands in the north.

Ibn Marwán: Marvão's role as stronghold for the Banu Marwan wilāya

Historical sources do not explain the precise role of Marvão castle itself within the 50-year statelet, or wilāya - established from 884-930 - controlled by Ibn Marwán, his son, grandson and great-grandson from Badajoz. While the territory of the Banu Marwan was extensive, covering much of modern-day Portugal and Extremadura, its autonomy within the Cordoban Emirate was precarious. It seems that the impenetrable fortification at Marvão acted as a deterrent to the Emirs in Córdoba. Sources quote a threat from Ibn Marwan, shortly after establishing his statelet in Badajoz 884, to 'destroy the new city' (i.e. Badajoz), and 'return to my Mountain' if Cordoban armies advance against him.[17]

Thus Marvão - 'my mountain' - became a piece of propaganda-in-stone for Ibn Marwán. With the Marwán dynasty possessing siege-ready castles such as this, and also engaged in realpolitik with the Asturian kings in times of conflict (a key ally being Alfonso III of Asturias), there was little to be gained for the Emirate from bringing this particular rebellious marcher-state into the fold. Fortresses such as those at Marvão would now deter any spring offensives against the Banu Marwan from the Emirate in Córdoba. These offensives by the Emirate were common against another rebellious muwallads, notably those against Umar Ibn Hafsun, based in Bobastro near Ronda. However, the relative peace and endurance of the Banu Marwan´s statelet - 46 years - testifies to the impregnability of its castles: any Emirate offensive in the São Mamede would be a bloodbath.

During its latter years, the Banu Marwan's statelet faced a major threat from reconquista-focused Christian kings from emergent states in the north. While Marvão is likely to have not been attacked in the raids of the king of León Ordoño II in 913 (which ransacked Evora to the south), it is likely to have suffered during raids during Ordoño II´s campaign to sack Mérida in 913.

Marvão under the Cordoban Caliphate

Prior to obtaining surrender from Ibn Marvan's great-grandson, in 929 CE, the Umayyad ruler Abd-al-Rahman III had proclaimed himself Caliph of the Caliphate of Córdoba. The Umayyad Caliphate heralded a century of economic boom, maturity in governmental structures, and cultural splendour in al-Andalus, which collapsed only in the year 1008 (finally dissolving in 1031). The São Mamede mountains around Marvão are likely to have benefited during the 10th-11th century alongside the rest of al-Andalus: population increased as hamlets (aldeias) of smallholdings expanded from villas (although, in Marvão, never reaching the levels of roman Ammaia); new shepherding pathways (karrales) criss-crossed Roman roads (calçadas), providing the dense network of mountain pathways seen today; irrigation technology and land-terracing improved, notably using gravity-flow water chutes (as-sāqiya); new crops (e.g. the doñegal fig, mulberry for silk production, citrus trees) and farming knowledge enabled more summer harvests and diversification away from the traditional vine, olive, cork oak and fig; Jewish and Christian communities were allowed considerable freedoms; some immigration occurred, with increases in the numbers of Berbers and Slavs (saqaliba, from central Europe - a notable Slav, Sabur, would be the first ruler of the taifa of Badajoz), deemed caliphate 'loyalists'.[18] Martial traditions were kept alive by recruitment of youths to fight in summer campaigns (aceifas) against the Christian north.[19]

Marvão under the Badajoz taifa and the Aftasids

The 11th century was to prove far less stable than the 'golden age' of Umayyad al-Andalus in the 10th century. As powerbase-fortress, Marvão is likely to have played a role in civil wars among internal factions in the Badajoz taifa during the 1020-1040s. Notably, the short-lived Taifa of Lisbon (1022-1045) was to challenge Aftasid dominance in Badajoz along the traditional land trade routes linking the Tagus through the São Mamede sierra (Santarem-Caceres). The Lisbon taifa was eventually reincorporated into the taifa of Badajoz in 1045 under Al-Muzaffar.

Such in-fighting was matched by external wars. Given its location and long line-of-sight into the Tagus basin, Marvão represented an important strategic base in the continual Muslim-Christian warring along the Lower March. In 1055, a large stretch of Moorish territory south of the Mondego river fell to the kingdom of León and Castile, led by king Ferdinand the Great (1015-1065). Coimbra would follow in 1064, and, under Ferdinand's son Alfonso VI, the vital city of Toledo in 1085. Such military successes enabled the Christian kings to exact onerous tributes, or parias, from the taifas in the south from 1055 onwards. Further, summer raiding campaigns from both Christian and Moorish forces effectively meant that the regions between the Douro river and Tagus were under continual threat - the lands south of the Douro and to the north of the Tagus became a depopulated 'buffer zone' between Christian and Moor. In 1063, a major razzia by Ferdinand sacked towns across the Seville and Badajoz taifas, and the São Mamede mountains lay en route. To make matters worse, the taifa of Badajoz was also fighting a war on its southern front: the taifa of Seville, under the poet-emirs Al-Mutamid and Al-Mutatid - was eating into territories in the Algarve . Thus throughout this period, Marvão and its neighbouring towns would have experienced the many tribulations of a martial state: the payment of taxes for wars and the paria protection money; the recruitment of its sons for battle; the billeting of any marching armies; occasional skirmishes during summer raiding campaigns; and the splitting of families during civil war.

Meanwhile, León and Castile were able to profit from the in-fighting. The Christian reconquista was moving southwards. Thus Marvão - as under Ibn Marwan - took up its deterrent role as a frontier fortress to project power beyond the court at Badajoz. Muslim domination in the region seemed on the back foot until the Battle of Sagrajas (near Badajoz, south of Marvão) in 1086. In the face of the Christian threat, the taifa emirs jointly called for assistance from Almoravid Africa under Yusuf ibn Tashfin. This crucial battle would re-establish Islamic dominance in the São Mamede for a further 70 years. The Battle of Sagrajas saw a crushing defeat of Castilian and Aragonese forces. However, for the forces of the Badajoz taifa - no doubt including fighters from Marvão - the battle of Sagrajas was a pyrrhic victory. The camp of their emir, al-Mutawakkil ibn al-Aftas, was sacked early on the morning of the battle, with many soldiers lost. The military strength of the Badajoz taifa was now much-weakened, and the Christians took advantage of this: as part of the paria tribute, the lower Tagus cities of Lisbon and Santarem were ceded in 1093 to Alfonso VI, as the Badajoz taifa attempted to defend itself from Almoravid dynasty. This effort would fail: the emir would be killed by Almoravids a year later.

The final generations of Islamic rule in Marvão: Almoravids, Almohads, reconquest

The Almoravids are described as austere, battle-ready jihadists - who contrasted greatly with the luxury-accustomed poet-emirs of the taifa era. They were not merely interested in defending the realm, but made frequent incursions into Christian territories. The period has been described as one of 'an illiterate military caste controlling, but apart from, the native society'.[20] It is likely that, alongside the rest of al-Andalus, Marvão experienced a number of key features of Almoravid rule: the introduction of illiterate Berber fighters from the Maghreb; drafting of its youth for military campaigns against the Christians (notably against Coimbra and Leiria) and Zaragoza taifa; a rise in religious fundamentalism; increased suppression of, and intolerance towards, Christian and Jewish communities, including forced conversion to Islam; religious cleansing (many Andalusi Christians were removed to Morocco).

Almoravid rule was not to last. They faced revolts at home in Morocco from a rival fundamendalist sect, the Almohads. Their tenuous hold on south west al-Andalus (the former Badajoz taifa and the Al-Garb) showed upon the death of the second Almoravid emir Al in Yusuf in 1143. An Algarve-centred rebellion by a Sufi sect, the al-Muridin - aided by Almohad arms - destabilised the region and set up a number of 'second taifa kingdoms' in Silves, Mértola and Tavira in the south. As well as being on the front line against the Christians, the São Mamede mountains are likely to have been on the northern edges of troop movements by the al-Muridin leader, Ibn Qasi and Almohad forces, against Almoravid centres of government (from 1146-1151). Indeed, collaboration and intrigue between Ibn Qasi, the Almohads, and a new Christian power - the fledgling Portugal, under Alfonso I of Portugal - is likely to have weakened the defensibility of the entire Tagus basin.

In the midst of complex conflicts and territorial grabs between Almohads, Alfonso I, Ferdinand II and Geraldo Sem Pavor, after nearly 500 years of Islamic rule, Marvão fell to Alfonso I during military campaigns in 1166. This conquest was by no means definitive. In 1190, a major Almohad counter-offensive launched from Morocco under Abu Yusuf Ya'qub al-Mansur retook Marvão, during a campaign against the Templar stronghold of Tomar which would recapture for the Moors much of the Algarve and the Alentejo as far as the castle at Alcácer do Sal. Further, a famous victory for the Almohads in the Guadiana valley at Alarcos, in 1195, re-established Muslim control over many lands south of the Tagus (including Trujillo and Talavera). It is likely that Marvão at this point saw similar reinforcement of its fortifications, as seen at Cáceres and Trujillo. For the following thirty years, Marvão remained on the margins of a battlezone that would ultimately determine the location of today's Portuguese-Spanish border.

The Kingdom of Portugal, the plantation of settlers, Templars and Hospitallers

Following its conquest by Alfonso I in the 1160s, and its brief recapture by Almohads in the 1190s, Marvão's situation remained fragile around the start of the 13th century: it was listed among Portuguese territories only in the termo of Castelo Branco in 1214. Marvão was a recently conquered outpost, that needed to be fully integrated into Portugal, and which stood on the edge of territories conquered by an expansionist Kingdom of León. The process of Portuguesification began under the reigns of kings Sancho I and Alfonso II. Yet it was the famous Christian victory over the Almohads at Navas de Tolosa (near Jaén) in 1212 - leaving 100,000 Moors dead - that would effectively secure this area of south-western Iberia, and establish a lasting peace. The São Mamede mountains and Guadiana valleys now became a bridgehead from which the reconquista could make strong inroads into Almohad territory in the Southern Alentejo, Algarve, Southern Extremadura and north-west Andalusia.

Marvão's role as fortress now became more important not as a Christian or Moorish outpost-against-the-infidel, but as a territorial marker for the young - and by no means militarily strong - state of Portugal against the competing Christian Kingdom of León. In 1226, Marvão was among the earliest towns on the eastern border to receive from Sancho II of Portugal its foral (i.e. royal charter, allowing the town to regulate its administration, borders and privileges).

Another aspect of 13th century statecraft that would bolster the area's 'Portugalidade' (Portuguese identity) would be the settlement of planted Christian colonists from the north (Galicia, the Minho), southern France and Flanders in territories around Marvão. This was done with royal approval, and with the intermediation of the Templars and Hospitallers. The resettlement of barren areas depopulated by centuries of warfare and bloodshed - or simply abandoned by fleeing Berber refugees - was vital to sustain the new Portuguese kingdom. Many of these settlers were Galicians, and the name of the hamlet of Galegos in Marvão is likely to refer to its 13th–14th century settlers. Other nearby settlements took names from southern France: in the nearby Templar-controlled village of Nisa (Nice), we find hamlets named Tolosa (Toulouse), Montalvão (Montauban) and Arez (Arles) to denote the origins of their settlers.[21]

Marvão´s castle: an archetype of medieval castle-building

As with other 11th-13th-century castles, the early medieval improvements and development of Marvão castle reflect the innovations brought back by crusading orders from the near east (notably the highly influential Hospitaller castle in Syria, the Krak des Chevaliers). The medieval castle seen in Marvão today mostly post-dates the year 1299, and features numerous characteristic features of a crusader-era castle: a tall central keep with raised entrance on the first floor; a series of lower, outlying turrets (some semi-circular); high-placed arrow-slits; open spaces to aid the sheltering and assembly of villagers and troops; a well, and huge rain-collecting cistern to supply water to both keep and the wider castle in the event of siege; bent entrances (both on the village and castle gates) to slow down invaders in the event of breached gates; a series of narrow killing zones (notably, in the triple gate on the village-side of the castle); extensive crenellated battlements and curtain walls that enhanced the natural defences provided by the escarpments of Marvão's rock.[24]

-

The convent of Nossa Senhora da Estrela.

-

The village within its castle walls.

-

Curtain wall of the village, with Castelo de Vide in the distance.

-

Front view of the castle.

Demographics

| Population of Marvão Municipality (1801–2004) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 1849 | 1900 | 1930 | 1960 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2004 |

| 4048 | 3780 | 5994 | 7116 | 7478 | 5418 | 4419 | 4029 | 3739 |

External links

| |||||

References

- ↑ Waymarking.com, 2011-07-07, retrieved 2012-07-24

- ↑ Greenfield, Beth, 'Seeing for Miles From a Village High in the Sky', New York Times, 2007-04-27, retrieved 2012-07-24

- ↑ 'The Hills of Alentejo', Geoffrey Bles, London, 1958

- ↑ de Oliveira, J., 'Monumentos megaliticos da bacia hidrografica do Rio Sever', 1997, ISBN 972-97626-0-0

- ↑ de Oliveira, J., 'Antas e Menires do Concelho de Marvão', in Ibn Maruan, Revista Cultural do Concelho de Marvão no. 8, 1998, ISSN 0872-1017

- ↑ Thomas, J..T. (2009), 'Approaching Specialisation: Craft Production in Late Neolithic/Copper Age Iberia', Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, University College London

- ↑ Haitlinger, P., Comunicação, antes das letras: Placas de Xisto Gravadas

- ↑ Da Silva, L., Map of 'Pre-Roman Peoples and Languages of Iberia, Associação Campo Arqueológico de Tavira, Tavira, Portugal. Map of 2010-03-13, Accessed 2012-07-24

- ↑ Gordalina, Domingos; Estadão, Luísa (2007). "Ruínas Romanas/Cidade romana de Ammaia". In SIPA (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico.

- ↑ Cillán, Adela, 'Ammaia, una ciudad romana por descubrir', Sevilla Press, 2012-05-16, retrieved 2012-07-24

- ↑ Corsi, M.; Deprez, F.; Vermeulen (September 2008), "Geoarchaeological Research in the Roman Town of Ammaia (Alentejo, Portugal)", Multudisciplinary Approaches to Classical Archaeology-Approcci Multidisciplinari per l'Archeologia Classica. Proceedings of the 17th International Congress of Classical Archaeology, Rome, Italy, pp. 22–26

- ↑ Cillán, Adela, 'Ammaia, una ciudad romana por descubrir', Sevilla Press, 2012-05-16, retrieved 2012-07-24

- ↑ Sidarus, Adel, 'Ammaia de Ibn Maruán: Marvão', in Ibn Maruan, Revista Cultural do Concelho de Marvão, November 1991

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard (1992), Moorish Spain, p. 44, ISBN 978-1-8421-2605-9

- ↑ Molina, Luis, http://digital.csic.es/bitstream/10261/12351/1/Molina_Vencedor.pdf 'VENCEDOR Y VENCIDO: HASIM B. ABD AL-AZIZ FRENTE A IBN MARWAN', Escuela de Estudios Árabes, CSIC, Granada

- ↑ Sidarus, Adel, 'Ammaia de Ibn Maruán: Marvão', in Ibn Maruan, Revista Cultural do Concelho de Marvão, November 1991

- ↑ Sidarus, Adel, 'Ammaia de Ibn Maruán: Marvão', in Ibn Maruan, Revista Cultural do Concelho de Marvão, November 1991

- ↑ Glick, Thomas F., 'Islamic and Christian Spain in the Early Middle Ages', in THE LIBRARY OF IBERIAN RESOURCES ONLINE

- ↑ Hitchcock, R., 'Muslim Spain (711-1492)', in Spain: A Companion to Spanish Studies (ed. Russell, P.E., 1973) ISBN 0-416-84110-4

- ↑ Fletcher, Richard (1992), Moorish Spain, p. 44, ISBN 978-1-8421-2605-9

- ↑ http://www.cm-nisa.pt/nisa_historia.htm

- ↑ http://www.cm-nisa.pt/nisa_historia.htm

- ↑ http://www.csarmento.uminho.pt/docs/ndat/rg/RG106_11.pdf

- ↑ Castelo de Marvão - detalhe