Martineau family

The Martineau Family was a political dynasty from Birmingham, England. Several of them were prominent Unitarians, to the extent that a room in Essex Hall, the headquarters building of the British Unitarians, was named after them.

Mayors of Birmingham

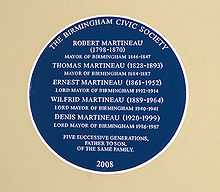

Members included five generations, father to son, of Mayors or Lord Mayors of Birmingham:[1][2]

- Robert Martineau (1798–1870), Mayor of Birmingham, 1846–47

- Thomas Martineau (1828–1893), Mayor of Birmingham, 1884–85

- Ernest Martineau (1861–1952), Lord Mayor of Birmingham, 1912–14

- Wilfrid Martineau (1889–1964), Lord Mayor of Birmingham, 1940–41

- Denis Martineau (1920–1999), Lord Mayor of Birmingham, 1986–87

A blue plaque, erected in 2008 by the Birmingham Civic Society, in Birmingham Council House commemorates all five.

Martineau family of Norwich

The Norwich Martineaus were founded by Huguenot immigrants, and were noted in the medical, intellectual and business fields.[3] They were initially Calvinist dissenters, who brought their children up as bilingual in French and English.[4] The founder, Gaston Martineau, was a surgeon in Dieppe, and moved to Norwich after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes of 1685.[5] His grandson David Martineau II (1726–1768) was the third generation of surgeons, and had five sons who made up the male line of Martineaus. By the fourth generation the family was divided into Anglicans and Unitarians.[6]

The eldest of the five sons was Philip Meadows Martineau (1752–1829), surgeon and "one of the most distinguished Lithomists of his day".[7][8] Apprenticed to the surgeon William Donne, who was noted for skill in lithotomy, he became a medical student at a number of universities, then returned in 1777 to become Donne's partner, and carried on his speciality. Henry Southey was his student.[9] He had one daughter. The second son David Martineau (four sons, six daughter) was a dyer who went into the sugar business. The third, Peter Finch Martineau (four sons, two daughter) was a dyer in Norwich. The fourth son, John Martineau of Stamford Hill, had 14 children, including John Martineau the engineer. The fifth son Thomas is mentioned below.[10]

Family of Thomas Martineau

Several of the Martineaus are buried in Key Hill Cemetery, Birmingham, either in the family grave or a separate one.[11]

Thomas Martineau, a manufacturer of textiles, was the fifth son of David Martineau II.[6][12] He was a Unitarian, a deacon of the Octagon Chapel from 1797.[13] He married Elizabeth Rankin (8 October 1772 – 26 August 1848). They lived in Norwich and had eight children.

- Their daughter, Elizabeth, married Thomas Michael Greenhow, a reforming doctor in Newcastle.

- Their child Frances married into the Luptons of Leeds and worked to expand educational opportunities for girls. She is one of the ancestors of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge.

- Their son, Robert, became a magistrate, town councillor and then Mayor of Birmingham in 1846.

- His son, Thomas (4 November 1828 – 28 July 1893), was Mayor of Birmingham 1884-7. He was knighted after receiving Queen Victoria to lay the foundation stone for the Victoria Law Courts, Birmingham.

- His son, Robert Francis (16 May 1831 – 15 December 1909) was a town councillor in Birmingham, secretary of the Birmingham and Midland Institute, chairman of the Technical School committee, trustee to Mason Science College, and then a member of the council of the University of Birmingham when it evolved from Mason College.

- Their sixth child, Harriet (12 June 1802 – 27 June 1876), was a political author and a pioneer sociologist.

- Their seventh child, James (21 April 1805 – 11 January 1900), was a religious philosopher and a professor at Manchester New College.

- Their daughter, Elizabeth, married Thomas Michael Greenhow, a reforming doctor in Newcastle.

References

- ↑ Birmingham City Council, List of Birmingham Mayors et seq

- ↑ The Blue Plaque itself

- ↑ Deborah Anna Logan (29 December 2011). Harriet Martineau and the Irish Question: Condition of Post-famine Ireland. Lexington Books. pp. 128 note 104. ISBN 978-1-61146-096-4. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ George Ritzer (15 April 2008). The Blackwell Companion to Major Classical Social Theorists. John Wiley & Sons. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-470-99988-2. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ James Drummond; C. B. Upton (1 July 2003). Life and Letters of James Martineau 1902. Kessinger Publishing. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-7661-7242-5. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 David C. A. Agnew (1871). Protestant Exiles from France in the Reign of Louis XIV, or, The Huguenot Refugees and Their Descendants in Great Britain and Ireland. Reeves & Turner; Edinburgh : William Paterson. p. 239. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ Shaw, A.Batty (1970). "Norwich School of Lithotomy". Medical History 14 (3): 221-259. PMID 4921977. Retrieved 21 January 2014.

- ↑ Harriet Martineau (1983). Harriet Martineau's Letters to Fanny Wedgewood. Stanford University Press. p. 92 note 3. ISBN 978-0-8047-1146-3. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ C. B. Jewson (1975). The Jacobin City: A Portrait of Norwich 1788–1802. Blackie & Son. pp. 126–8. ISBN 0 216 89874 9.

- ↑ Charles Harold Evelyn-White, The East Anglian; or, Notes and queries on subjects connected with the counties of Suffolk, Cambridge, Essex and Norfolk New Series vol. 1 (1886) pp. 53–5; archive.org.

- ↑ Official Guide to the Birmingham General Cemetery, E. H. Manning, Hudson & Son, Livery Street, Birmingham, 1915. Birmingham Public Libraries (Reference, Local Studies, B.Coll 45.5)

- ↑ Autobiography, Harriet Martineau, ed. Linda H. Peterson.

- ↑ C. B. Jewson (1975). The Jacobin City: A Portrait of Norwich 1788–1802. Blackie & Son. pp. 141–2. ISBN 0 216 89874 9.