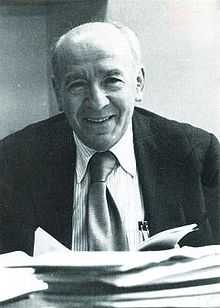

Mark Kac

| Mark Kac | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

August 3, 1914 Krzemieniec, Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine) |

| Died |

October 26, 1984 (aged 70) California, USA |

| Residence | USA |

| Citizenship | Poland, USA |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Fields | Mathematics |

| Institutions |

Cornell University Rockefeller University University of Southern California |

| Alma mater | Lwów University |

| Doctoral advisor | Hugo Steinhaus |

| Doctoral students |

Harry Kesten William LeVeque William Newcomb Lonnie Cross Murray Rosenblatt Daniel Stroock |

| Known for |

Feynman–Kac formula Erdős–Kac theorem |

| Notable awards | Birkhoff Prize (1978) |

Mark Kac (/kɑːts/ KAHTS; Polish: Marek Kac; 3 August 1914 – 26 October 1984) was a Polish mathematician.[1] His main interest was probability theory. His question, "Can one hear the shape of a drum?" set off research into spectral theory, with the idea of understanding the extent to which the spectrum allows one to read back the geometry. (In the end, the answer was "no", in general.)

Kac completed his Ph.D. in mathematics at the Polish University of Lwów in 1937 under the direction of Hugo Steinhaus.[2] While there, he was a member of the Lwów School of Mathematics. After receiving his degree he began to look for a position abroad, and in 1938 was granted a scholarship from the Parnas Foundation which enabled him to go work in the United States. He arrived in New York City in November, 1938.[3] With the onset of World War II, Kac was able to remain in America, while his parents and brother who remained in Poland were murdered by the Germans in the mass executions in Krzemieniec (1942–43) for being Jewish.[4] From 1939 until 1961 he was at Cornell University, first as an instructor, then from 1943 as assistant professor and from 1947 as full professor.[5] While there, he became a naturalized US citizen in 1943. In the academic year 1951–1952 Kac was on sabbatical at the Institute for Advanced Study.[6] In 1952 Kac, with Theodore H. Berlin, introduced the spherical model of a ferromagnet (a variant of the Ising model)[7] and, with J. C. Ward, found an exact solution of the Ising model using a combinatorial method.[8] In 1961 he left Cornell and went to Rockefeller University in New York City. In the early 1960s he worked with George Uhlenbeck and P. C. Hemmer on the mathematics of a van der Waals gas.[9] After twenty years at Rockefeller University, he moved to the University of Southern California where he spent the rest of his career.

Reminiscences

- His definition of a profound truth. "A truth is a statement whose negation is false. A profound truth is a truth whose negation is also a profound truth."

- He preferred to work on results that were robust, meaning that they were true under many different assumptions and not the accidental consequence of a set of axioms.

- Often Kac's "proofs" consisted of a series of worked examples that illustrated the important cases.

- When Kac and Richard Feynman were both on the Cornell faculty he went to a lecture of Feynman's and saw that the two of them were working on the same thing from different directions. The Feynman-Kac formula resulted, which proves rigorously the real case of Feynman's path integrals. The complex case, which occurs when a particle's spin is included, is still unproven. Kac had learned Wiener processes by reading Norbert Wiener's original papers, which were "the most difficult papers I have ever read."[3] Brownian motion is a Wiener process. Feynman's path integrals are another example.

- Kac's distinction between an "ordinary genius" like Hans Bethe and a "magician" like Richard Feynman has been widely quoted. (Bethe was also at Cornell University.)

- Kac became interested in the occurrence of statistical independence without randomness. As an example of this, he gave a lecture on the average number of factors that a random integer has. This wasn't really random in the strictest sense of the word, because it refers to the average number of prime divisors of the integers up to N as N goes to infinity, which is predetermined. He could see that the answer was c log log N, if you assumed that the number of prime divisors of two numbers x and y were independent, but he was unable to provide a complete proof of independence. Paul Erdős was in the audience and soon finished the proof using Sieve theory, and the result became known as the Erdős–Kac theorem. They continued working together and more or less created the subject of Probabilistic number theory.

- Kac sent Erdős a list of his publications, and one of his papers contained the word Capacitor in the title. Erdős wrote back to him "I pray for your soul."

- Kac got a typed manuscript back from his secretary and it contained the following sentence "This result can be verified by connecting 300 volts across a negro gentleman." He looked at his handwritten draft to see what could possibly have produced this, and it said "This result can be verified by connecting 300 volts across a rigger," which was a Breadboard.

Books

- Mark Kac and Stanislaw Ulam: Mathematics and Logic: Retrospect and Prospects, Praeger, New York (1968) Dover paperback reprint.

- Mark Kac, Statistical Independence in Probability, Analysis and Number Theory, Carus Mathematical Monographs, Mathematical Association of America, 1959.[10]

- Mark Kac, Probability and related topics in the physical sciences. 1959 (with contributions by Uhlenbeck on the Boltzmann equation, Hibbs on quantum mechanics, and van der Pol on finite difference analogues of the wave and potential equations, Boulder Seminar 1957).[11]

- Mark Kac, Enigmas of Chance: An Autobiography, Harper and Row, New York, 1985. Sloan Foundation Series. Published posthumously with a memoriam note by Gian-Carlo Rota.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ Obituary in Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, 11 November 1984

- ↑ Mark Kac at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mark Kac, Enigmas of Chance: An Autobiography, Harper and Row, New York, 1985. ISBN 0-06-015433-0

- ↑ M Kac, Enigmas of chance : an autobiography (California, 1987)

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Mark Kac", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- ↑ Kac, Mark, Community of Scholars Profile, IAS

- ↑ Berlin, T. H.; Kac, M. (1952). "The spherical model of a ferromagnet". Phys. Rev. 86: 821–835. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.86.821.

- ↑ Ward, J. C. (1952). "A combinatorial solution of the two-dimensional Ising model". Phys. Rev. 88: 1332–1337.

- ↑ Cohen, E. G. D. (April 1985). "Obituary: Mark Kac". Physics Today 38 (4): 99–100. doi:10.1063/1.2814542.

- ↑ LeVeque, W. L. (1960). "Review: Statistical independence in probability, analysis and number theory, by Mark Kac. Carus Mathematical Monographs, no. 12". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. 66 (4): 265–266.

- ↑ Baxter, Glen (1960). "Review: Probability and related topics in the physical sciences, by Mark Kac". Bull. Math. Soc. 66 (6): 472–475.

- ↑ Birnbaum, Z. W. (1987). "Review: Enigmas of chance; an autobiography, by Mark Kac". Bull. Amer. Math. Soc. (N.S.) 17 (1): 200–202.

External links

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Mark Kac |

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Mark Kac", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Mark Kac at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

|