Maria Kuryluk

Maria (Mia) Kuryluk, 24 December 1917–1 January 2001, was a poet, writer, translator, and amateur pianist. She was first married to Teddy Gleich (1912–1946), then to Karol Kuryluk (1910–1967). She was the mother of Ewa Kuryluk and Piotr Kuryluk (1950–2004).

Biography

Maria Kuryluk, called Mia by her family and friends, was born Miriam Kohany in an assimilated Jewish family in Bielsko-Biała, Silesia, and died in Warsaw. She was the eldest daughter of the merchant Herman Kohany (1882–1942) who perished in the Holocaust under unknown circumstances, and Paulina Kohany, née Raaber (1882–1942), a porcelain designer in her youth, who was killed along with her younger daughter Hilde Kohany (1920–1942) in Treblinka. Miriam’s older brother Oscar survived the war in the Soviet Union and in 1950 emigrated with his family from Poland to Israel.

Before World War II

All members of the Kohany family were bilingual, fluent in German and Polish, and both parents and their daughters played piano. Miriam Kohany also had a good command of French and Russian, and was an avid reader of poems and novels. Her favorite authors were Goethe, Hölderlin, Kleist, Pushkin and Thomas Mann. After graduating from a Protestant German high school for girls in Bielsko, she held clerical jobs and was involved in the Zionist Youth Movement. She also gave small piano concerts, participated in theatrical performances and was, not unlike her younger sister Hilde, a cinema fan. Miriam greatly admired the actress Erika Mann and became acquainted with her when Mann’s famous anti-fascist cabaret Die Pfeffermühle toured Silesia.

World War II

Shortly after World War II started in September 1939, Miriam Kohany fled with her husband and elder brother from Bielsko-Biała to Lvov (today Lviv in the Ukraine) with a group of young people, dispersed on the way. By the time she arrived in Lvov the city had been annexed by the Soviets. Nothing is known about the following two years of Miriam’s whereabouts under the Soviet occupation, except that she continued writing poetry. In 1942 Miriam Kohany escaped from the Lvov ghetto and survived, as did her husband Teddy Gleich, on the Aryan side with the help of Karol Kuryluk, a member of the resistance.

While in hiding from 1942 to 1944, Miriam Kohany joined the underground and worked for clandestine news and publishing services. She kept writing poetry, made notes about Heinrich von Kleist and began a novel about her family, disguised as the family of Lena and Robert Buch. In 1944, with the Red Army closing on Lvov, she acted as liaison and ventured into the for-Germans-only parts of the city distributing leaflets calling on Wehrmacht soldiers to desert.

After World War II

In August 1944 Karol Kuryluk became the editor-in-chief of “Odrodzenie” (“The Renaissance”), a cultural magazine first published in Lublin, later in Cracow and Warsaw—and Maria Kuryluk became responsible for the magazine’s correspondence, tracking down contributors all over Europe. Her job’s difficulty is evidenced by the military censorship stamp on the envelope of André Malraux’s letter of 4 August 1945, responding to Maria Kuryluk’s request to contribute an excerpt of his novel to “Odrodzenie”.

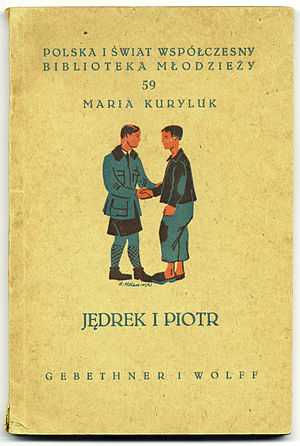

Towards the end of the war Maria Kuryluk switched from writing in German to writing in Polish. Her first book Jędrek i Piotr, a short novel about war orphans she had taken care of in Cracow, was serialized in “Odrodzenie” and published in Warsaw in 1946. Unpublished, however, remained her principle early work, a long wartime memoirs with autobiographical elements entitled Zdzisław Bieliński (ca. 1946): the name of a Lvov doctor who saved Jews along with his wife Zofia Bielińska. Doctor Bieliński was killed in 1945 by radicals of the Polish nationalist underground. The Bieliński couple was later declared as Righteous among the Nations of the World by Yad Vashem, but their heroic deeds became known in detail only recently, when Ewa Kuryluk discovered and published excerpts from her mother’s memoirs in her novel Frascati[1] (2009).

In the fall of 1946, soon after the birth of her daughter Ewa in May, the Kielce Pogrom in July, and the sudden and still-unexplained death of Teddy Gleich in August, Maria Kuryluk fell into deep depression and developed schizophrenia. She decided to stay in hiding and to keep her war identity of Maria Grabowska, born in the town of Zbaraż, where her husband Karol Kuryluk was born. In mid-1950s, despite the challenges of raising two young children, and her poor health, she enrolled at the faculty of German at Poznań University, but did not complete her M.A. thesis on Thomas Mann’s novels.

In the years 1956–58, when Karol Kuryluk was minister of culture, Mia Kuryluk played a decisive role in bringing Western art and artists to Poland. She hosted Vivien Leigh, Laurence Olivier, Gerard Philipe and Yves Montand at their modest apartment on Frascati Street.[1] In January 1959, when Karol Kuryluk was appointed Polish ambassador to Austria, she moved with her husband and children to Vienna. In Austria her health deteriorated and she was repeatedly confined to a psychiatric clinic. Yet she still pursued her literary and artistic interests, reestablished contact with Erika Mann, befriended the writer and pacifist Thomas, and translated poetry by Erich Fried, Ingeborg Bachmann, Thomas Bernhard.

After her husband’s sudden death in 1967 Mia Kuryluk supplemented her meager pension by giving private German and French lessons, working as librarian at the Austrian Institute[2] in Warsaw, and advising Polish publishers on contemporary German and Austrian literature. She continued translating Austrian and German poetry until her death.

Mia Kuryluk is buried with her husband Karol and her son Piotr at the Warsaw Powązki Cemetery in a tomb designed by Ewa Kuryluk.[3]

Literary work

Maria Kuryluk’s short stories, journalism and translations into Polish were published in the magazines “Odrodzenie”, “Nowa Kultura” and “Zeszyty Literackie”.[4] Miriam Kohany’s writings in German, an impressive amount of prose fragments and over one hundred poems written before and during World War II, constitute a tragic testimony of a hidden life. This body of work was only recently rediscovered by Ewa Kuryluk, and still remains to be published. Miriam Kohany’s earliest poems go back to 1936. Some deal with love and the beauty of nature. Most address, however, philosophical and political themes, and their mood is dark. Hitler, the Führer, is called the terrible Verführer (seducer) of the German people, and the future is foreboding.

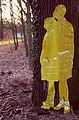

Ewa Kuryluk has commemorated her mother in her autobiographical novels Goldi (2004) and Frascati (2009), and in her textile installations Yellow Birds Fly (2001), Taboo (2005) and Triptych on Yellow Background (2010).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Maria Zawadzka, Warszawa (September 30, 2010). "In hardback – about "Frascati" by Ewa Kuryluk". Museum of the History of Polish Jews. Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Austrian Culture Institute". Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Ewa Kuryluk". Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- ↑ "Zeszyty Literackie". Retrieved 2011-03-03.

- Maria Kuryluk, Jędrek i Piotr, Warsaw, 1946.

- Maria Kuryluk, Zdzisław Bieliński, ca. 1946, excerpts published in Ewa Kuryluk, Frascati, Cracow, 2009, pp. 176–184.

- Tadeusz Breza, “Wspomnienie o Karolu”, in Nelly, Warsaw, 1970.

- Maria Dąbrowska, Dzienniki. 1914–1965, Warsaw, 2009.

- Anna Kowalska, Dzienniki 1927–1969, Warsaw, 2008.

- Ewa Kuryluk, Ludzie z powietrza—Air People, Cracow, 2002.

- Ewa Kuryluk, Goldi, Warsaw, 2004; second edition Cracow 2011.

- Ewa Kuryluk, Kangór z kamerą—Kangaroo with the Camera, Cracow and Warsaw, 2009.

- Ewa Kuryluk’s web site

External links

- Yad Vashem’s web site

- Ewa Kuryluk’s web site

- Ewa Kuryluk, Goldi, Warsaw, 2004

- Kuryluk Ewa Kuryluk

- an article about Ewa Kuryluk by Małgorzata Kitowska-Łysiak

- Historical article about Karol Kuryluk by his daughter Ewa.

- A Wikipedia page about Lvov

- The Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw

- An interview with Ewa Kuryluk about her parents and family.

- The Museum of the History of Polish Jews’ web page with English translations of Maria Kuryluk’s memoirs about the Bielinski family rescuing Jews during the German occupation of Lvov.

Picture gallery

-

Herman Kohany (1882–1942), father of Miriam Kohany, Olomütz, ca. 1914.

-

Paulina Raaber (1882–1942), Miriam Kohany’s mother, ca. 1900, photo: E. Bieber, Berlin, ca. 1900, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

Miriam Kohany (right) with her younger sister Hilde, ca.1933, photographer unknown, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

The art nouveau sunflower building designed 1901–1905 by A. Walczok at 2, Mickiewicz Street in Bielsko. Before World War II it was owned by Leo Kohany, perhaps a distant relative of Miriam Kohany’s family, photo by Ewa Kuryluk, 2003.

-

Frog Building, 1903, designed by Emanuel Rost Junior, Main Square in Biała, photo by Ewa Kuryluk.

-

Wartime identity papers of Miriam Kohany with her photo and the name of Maria Grabowska, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

Miriam Kohany, 1943, photo torn from an identity card, photographer unknown, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

A building on Zamarstynów Street in Lvov, once part of the ghetto from where Miriam Kohany fled, photo by Ewa Kuryluk, 2008.

-

A view of the former Lvov Ghetto, 2008, by Ewa Kuryluk.

-

Miriam Kohany, Chapter I of her autobiographical novel, 1942–3?, photo by Ewa Kuryluk, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

A letter from André Malraux to Maria Kuryluk, with a Polish military censorship stamp on the envelope, 1945, archive of Ewa Kuryluk, scan by Ewa Kuryluk.

-

Maria Kuryluk with her son Piotr, Zakopane, 1954, archive of Ewa Kuryluk, photographer unknown.

-

Maria Kuryluk with her children and her Chinese friend I Chang in front of their house on Frascati Street, Warsaw, 1957.

-

Maria Kuryluk with her son Piotr in Vienna, 1961, photographer unknown.

-

Maria Kuryluk with the Austrian President Adolf Schärf, Vienna, 1961, archive of Ewa Kuryluk, photographer unknown.

-

Maria Kuryluk with the Austrian painter Friedensreich Hundertwasser and a Chinese diplomat, Austrian Institute in Warsaw, ca. 1975, photographer unknown, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

An autographed photo of Laurence Olivier dedicated to Mia Kuryluk in 1957 when he and his wife Vivien Leigh paid a visit to the Kuryluk’s home on Frascati Street in Warsaw, photographer unknown, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

An autographed photo of Vivien Leigh dedicated to Mia Kuryluk in 1957 when she and her husband Laurence Olivier paid a visit to the Kuryluk’s home on Frascati Street in Warsaw, photographer unknown, archive of Ewa Kuryluk.

-

The grave designed in 1967 by Ewa Kuryluk for her father Karol where now also her mother and her brother are buried, Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw, photo by Ewa Kuryluk 1968.

-

Woman with Bird, a bronze stele made by Ewa Kuryluk in 1967 for her father’s grave on the Powązki Cemetery in Warsaw, photo by Ewa Kuryluk, 1968.

-

Miriam, drawing & collage on cotton by Ewa Kuryluk, part of the 2002 installation Yellow Birds Fly at the Zachęta National Gallery, Warsaw, photo by Ewa Kuryluk.

-

Hilde and Miriam, drawing on a silk cutout by Ewa Kuryluk, installed in Bois de Boulogne, Paris, part of the 2002 installation Yellow Birds Fly, photo by Ewa Kuryluk.