Mare Serenitatis

| Mare Serenitatis | |

|---|---|

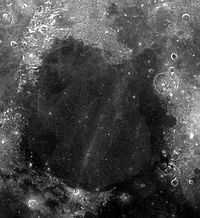

Photograph of Mare Serenitatis | |

| Coordinates | 28°00′N 17°30′E / 28.0°N 17.5°ECoordinates: 28°00′N 17°30′E / 28.0°N 17.5°E |

| Diameter | 674 km (419 mi)[1][2] |

| Eponym | Sea of Serenity |

Mare Serenitatis ("Sea of Serenity") is a lunar mare located to the east of Mare Imbrium on the Moon.

Geology

Mare Serenitatis It is located within the Serenitatis basin, which is of the Nectarian epoch. The material surrounding the mare is of the Lower Imbrian epoch, while the mare material is of the Upper Imbrian epoch. The mare basalt covers a majority of the basin and overflows into Lacus Somniorum to the northeast. The most noticeable feature is the crater Posidonius on the northeast rim of the mare.[3] The ring feature to the west of the mare is indistinct, except for Montes Haemus. Mare Serenitatis connects with Mare Tranquillitatis to the southeast and borders Mare Vaporum to the southwest. Mare Serenitatis is an example of a mascon, an anomalous gravitational region on the moon.

Names

Like most of the other maria on the Moon, Mare Serenitatis was named by Giovanni Riccioli, whose 1651 nomenclature system has become standardized.[4] Previously, William Gilbert had included it among the Regio Magna Occidentalis ("Large Western Region") in his map of c.1600.[5] Pierre Gassendi had included it among the 'Homuncio' ('little man'), referring to a small humanoid figure that he could see among the maria; Gassendi also referred to it as 'Thersite' after Thersites, the ugliest warrior in the Trojan War.[6] Michael Van Langren had labelled it the Mare Eugenianum ("Eugenia's Sea") in his 1645 map,[7] in honour of Isabella Clara Eugenia, queen of the Spanish Netherlands. And Johannes Hevelius included it within Pontus Euxinus (after the classical name for the Black Sea) in his 1647 map.

Exploration

Both Luna 21 and Apollo 17 landed near the eastern border of Mare Serenitatis, in the area of the Montes Taurus range. Apollo 17 landed specifically in the Taurus-Littrow valley.

In popular culture

- Mare Serenitatis forms one of the eyes for the Man in the Moon.

- In Sailor Moon, Mare Serenitatis was the former location of the Moon Kingdom.

- Mare Serenitatis is also mentioned in Arthur C. Clarke's The Sentinel.

- Most of the action in John Wyndham's 1933 short story "The Last Lunarians" takes place on the edge of the Sea of Serenity.

References

- ↑ "Moon Mare/Maria". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- ↑ "Mare Serenitatis". NASA Lunar Atlas. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ "Lunar Map". Central Coast Astronomical Society. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ Ewen A. Whitaker, Mapping and Naming the Moon (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.61.

- ↑ Ewen A. Whitaker, Mapping and Naming the Moon (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.15

- ↑ Ewen A. Whitaker, Mapping and Naming the Moon (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.33.

- ↑ Ewen A. Whitaker, Mapping and Naming the Moon (Cambridge University Press, 1999), p.41, 198.

| |||||||||||||||||