Marbella

| Marbella | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Municipality | |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

Marbella | |||

Marbella | |||

| Coordinates: 36°31′0″N 4°53′0″W / 36.51667°N 4.88333°WCoordinates: 36°31′0″N 4°53′0″W / 36.51667°N 4.88333°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Autonomous community |

| ||

| Province | Málaga | ||

| Comarca | Costa del Sol Occidental | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor-council | ||

| • Body | Ayuntamiento de Marbella | ||

| • Mayor | María Ángeles Muñoz Uriol (PP) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 114.3 km2 (44.1 sq mi) | ||

| • Land | 114.3 km2 (44.1 sq mi) | ||

| • Water | 0.00 km2 (0.00 sq mi) | ||

| Population (2012) | |||

| • Total | 140,473 | ||

| • Density | 1,228/km2 (3,180/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Website | www.marbella.es | ||

Marbella is a city and municipality in southern Spain, belonging to the province of Málaga in the autonomous community of Andalusia. It is part of the region of the Costa del Sol and is the headquarters of the Association of Municipalities of the region; it is also the head of the judicial district that bears its name.

Marbella is situated on the Mediterranean Sea, between Málaga and the Gibraltar Strait, in the foothills of the Sierra Blanca. The municipality covers an area of 117 square kilometres (45 sq mi) crossed by highways on the coast, which are its main entrances.

In 2012 the population of the city was 140,473 inhabitants,[1] making it the second most populous municipality in the province of Málaga and the eighth in Andalusia. It is one of the most important tourist cities of the Costa del Sol and throughout most of the year is an international tourist attraction, due mainly to its climate and tourist infrastructure.

The city also has a significant archaeological heritage,[2] several museums[3][4] and performance spaces,[5] and a cultural calendar[6] with events ranging from reggae concerts[7] to opera performances.[8]

Geography

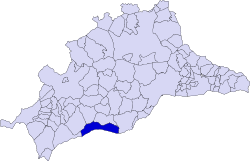

The Marbella municipality occupies a strip of land that extends along forty-four kilometres (27 miles) of coastline of the Penibético region, sheltered by the slopes of the coastal mountain range, which includes the Bermeja, Palmitera, Royal, White and Alpujata sub-ranges. Due to the proximity of the mountains to the coast, the city has a large gap between its north and south sides, thus providing views of the sea and mountain vistas from almost every part of the city. The coastline is heavily urbanised; most of the land not built up with golf courses has been developed with small residential areas. Map of Marbella. Marbella is bordered on the north by the municipalities of Istán and Ojén, on the northwest by Benahavís, on the west by Estepona and on the northeast by Mijas. The Mediterranean Sea lies to the south.

Topography

There are five geomorphological units: the Sierra Blanca, the Sierra Blanca piedmont (foothills), the lower hill country, the plains and the coastal dunes.[9] The Sierra Blanca is most centrally located in the province, looming over the old village. This mountain has three peaks: La Concha, located further west at 1,215 m above sea level, Juanar Cross, located eastward (within the municipality of Ojen) at 1,178 m above sea level, and the highest, Mount Lastonar, located between the two at 1,270 metres. Marbella's topography is characterised by extensive coastal plains formed from eroded mountains.[10] After the plain lies an area of higher elevations of between 100 and 400 m, occupied by low hills, behind which rise the foothills and steeper slopes of the mountains. The coast is generally low and sandy beaches that are more extensive further east, between the fishing port and the Cabopino. Despite the intense urbanisation of the coast, it still retains a natural area of dunes at the eastern end of town, the Artola Dunes (Dunas de Artola).

Hydrography

The entire region lies within the Andalusian Mediterranean Basin. The rivers are short and have very steep banks, so that flash floods are common.[11] These include the Guadalmina, the Guadaiza, the Verde and the Rio Real, which provide most of the water supply. The irregularity of rainfall has resulted in intermittent rivers that often run dry in summer; most of the many streams that cross the city have been bridged. The La Concepción reservoir supplies the population with drinking water; apart from this there are other reservoirs like El Viejo and El Nuevo (the Old and the New) that irrigated the old agricultural colony of El Ángel, and Las Medranas and Llano de la Leche that watered the plantations of the colony of San Pedro de Alcántara.

Climate

Marbella is protected on its northern side by the coastal mountains of the Cordillera Penibética and so enjoys a microclimate with an average annual temperature of 18 °C (64 °F). The highest peaks of the mountains are occasionally covered with snow, which usually melts in a day or two. Average rainfall is 628 l/m while hours of sunshine average 2,900 annually.[12]

Flora and fauna

Despite the pressure of urbanisation, remnants of the land in its natural state are still preserved in the mountains, where there are chestnut and cherry trees, reforested firs, Aleppo, Monterrey and maritime pines; pinyons, and ferns. The fauna is represented by golden eagles, Bonelli's eagles, short-toed eagles, hawks, falcons, vultures, genets or musk cats, badgers, wild goats, deer, martens, foxes and rabbits.[13]

The coast has the Natural Monument site of the Dunas de Artola, one of the few protected natural beaches of the Costa del Sol, which contains marram grass, sea holly, sea daffodils and shrubs such as large-fruited juniper.[14] A highlight of the marine ecosystem of the sea around Marbella is the Posidonia oceanica, a plant endemic to the Mediterranean, found in the Cabopino area.[15]

Demographics

According to the census of the INE for 2011, Marbella had a population of 135,124 inhabitants,[16] which ranked it as the second most populous city in the province of Málaga and eighth in Andalusia after supplanting Cádiz in 2008.[17][18] Unlike other towns in the Costa del Sol, Marbella had a significant population before the population explosion caused by the tourist boom of the 1960s. The census counted about 10,000 people in 1950; population growth since has been as spectacular as that of neighboring towns. Between 1950 and 2001 the population grew by 897%, with the decade of the 1960s having the highest relative increase, at 141%. In 2001, only 26.2% of Marbella's population had been born there, 15.9% were foreign-born, and those born in other towns in Spain made up the difference. During the summer months the population of Marbella increases by 30% with the arrival of tourists and foreigners who have their second homes in the area.[19]

The population is concentrated in two main centres: Marbella and San Pedro Alcántara; the rest is scattered in many developments in the districts of Nueva Andalucia and Las Chapas, located along the coast and on the mountain slopes. According to a study by the Association of Municipalities of the Costa del Sol, based on the production of solid waste in 2003, Marbella had a population of about 246,000 inhabitants, almost twice that of the population census of 2008. From the estimated volume of municipal waste in 2010, the City calculates the population during the summer months at around 400,000 people, while official police sources estimated it at about 500,000, with a peak of up to 700,000 people. [citation needed]

Gentilic names

Traditionally the people of Marbella have been called "marbelleros" in popular language, and "marbellenses" in the liturgy; these names have appeared in dictionaries and encyclopedias. However, since the mid-fifties, Marbellan residents have been called "marbellís" or "marbellíes", the only gentilic, or demonym, that appears in the Diccionario de la Lengua Española (Dictionary of the Spanish Language) published by the Royal Spanish Academy.[20]

The use of "marbellí" as a gentilic was popularised by the writer and journalist Victor de la Serna (1896–1958), who wrote a series of documentary articles on "The Navy of Andalucía"; in his research he had come upon the Historia de Málaga y Su Provincia (History of Málaga and the Province) by Francisco Guillén Robles, who used the plural word "marbellíes" to designate the Muslim inhabitants of Marbella.[21]

History

Prehistory and antiquity

Archaeological excavations have been made in the mountains around Marbella which point to human habitation in Paleolithic and Neolithic times. Some historians believe that the first settlement on the present site of Marbella was founded by the Phoenicians in the 7th century BC, as they are known to have established several colonies on the coast of Málaga province. However, no remains have been found of any significant settlement, although some artefacts of Phoenician and later Carthaginian settlements have been unearthed in different parts of the municipality, as in the fields of Rio Real and Cerro Torrón.[22]

The existence of a Roman population centre in what is now the El Casco Antiguo (Old Town) is suggested by three Ionic capitals embedded in one section of the Murallas del Castillo (Moorish castle walls), the reused materials of a building from earlier times. Recent discoveries in La Calle Escuelas (School Street) and other remains scattered throughout the old town testify to a Roman occupation as well. West of the city on the grounds of the Hotel Puente Romano is a small 1st-century Roman Bridge over a stream.[23] This bridge was part of the ancient Via Augusta that linked Rome to Cádiz. There are ruins of other Roman settlements along the Verde and Guadalmina rivers: Villa Romana on the Rio Verde (Green River), the Roman baths at Guadalmina, and the ruins of a Roman villa and an early Byzantine basilica at Vega del Mar, built in the 3rd century and surrounded by a paleo-Christian necropolis, later used as a burial ground by the Visigoths. All of these further demonstrate a continued human presence in the area. In Roman times, the city was called Salduba (Salt City).[24]

Middle Ages

During the period of Islamic rule, after the Normans lay waste to the coast of Málaga in the 10th century, the Caliphate of Córdoba fortified the coastline and built a string of several lighthouse towers along it. In the Umayyad fashion[25] they constructed a citadel, the Alcazaba, and a wall to protect the town,[26] which was made up of narrow streets and small buildings with large patios, the most notable buildings being the citadel and the mosque. The village was surrounded by orchards; its most famous crops were figs and mulberry trees for silkworm cultivation. The current name may have developed from the name the Arabs gave it: Marbil-la (ماربيا), which may in turn derive, according to some linguistic investigations, from a previous Iberian place name. The traveller Ibn Battuta characterised it as "a pretty little town in a fertile district."[27][28] During the time of the first kingdoms of Taifa, Marbil-la was disputed by the Taifas of Algeciras and of Málaga, eventually falling into the orbit of Málaga, which in turn later became part of the Nazarid Kingdom. In 1283 the sultan Marinid Abu Yusuf launched a campaign against the Kingdom of Granada. Peace between the Marinid dynasty and the Nasrid dynasty was achieved with the signing of the Treaty of Marbella on 6 May 1286, by which all the Marinid possessions in Al-Andalus were restored to the Nazarid sultan.[29]

Early modern age

On 11 June 1485 the town passed into the hands of the Crown of Castile without bloodshed. The Catholic Monarchs gave Marbella the title of city and capital of the region and made it a realengo (royal protectorate). The Plaza de los Naranjos was built along the lines of Castilian urban design about this time, and some of the historical buildings that surround it, as well. The Fuerte de San Luis de Marbella (Fort of San Luis) was built in 1554 by Charles V. The main door faced north and was protected by a moat with a drawbridge. Today, the ruins of the fort house a museum, and on the grounds are the Iglesia del Santo Cristo de la Vera Cruz (Church of the Holy Christ of the True Cross) and Ermita del Calvario (Calvary Chapel). Sugar cane was introduced to Marbella in 1644, the cultivation of which spread on the Málaga province coast,[30] resulting in the construction of numerous sugar mills, such as Trapiche del Prado de Marbella.

- 19th century

In 1828 Málaga businessman Manuel Heredia founded a company called La Concepción[31] to mine the magnetite iron ores[32] of the Sierra Blanca at nearby Ojén, due to the availability of charcoal made from the trees of the mountain slopes and water from the Verde River, as a ready supply of both was needed for the manufacture of iron. In 1832 the company built the first charcoal-fired blast furnace for non-military use in Spain;[33] these iron-smelting operations ultimately produced up to 75% of the country's cast iron. In 1860 the Marqués del Duero founded an agricultural colony, now the heart of San Pedro de Alcántara.[34] The dismantling of the iron industry based in the forges of El Angel and La Concepción occurred simultaneously, disrupting the local economy, as much of the population had to return to farming or fishing for a livelihood. This situation was compounded by the widespread crisis of traditional agriculture, and by the epidemic of phylloxera blight in the vineyards,[35] all of which accounted for Marbella's high unemployment, increase in poverty, and the starvation of many day labourers.

The associated infrastructure built for the installation of the foundry of El Angel in 1871 by the British-owned Marbella Iron Ore Company[36] temporarily relieved the situation, and even made the city a destination for immigrants, increasing its population. However, the company did not survive the worldwide economic crisis of 1893, and closed its doors in that year due to the difficulty of finding a market for the magnetite iron ore removed from its mine.[37]

In the late 19th century, Marbella was a village composed of three parts: the main districts, the Barrio Alto or San Francisco, and the Barrio Nueveo. There were three smaller nuclei arranged around the old ironworks and the farm-model of the colony of San Pedro Alcántara, as well as isolated dwellings in orchards and farms. The general population was divided between a small group of oligarchs and the working people, the middle class being practically non-existent.

20th century

In the early decades of the century the first hotels were built: the El Comercial, which opened in 1918, and the Miramar, which opened its doors in 1926.[38] During the Second Republic, Marbella experienced major social changes driven by the mobilisation of contentious political parties. At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War, Marbella and Casare suffered more anticlerical violence than the rest of the western part of Málaga province. Several religious buildings in the city were burned the day after the failed uprising that led to the Civil War, including the Church of St. Mary of the Incarnation and the Church of San Pedro Alcantara, of which only the walls were left standing.[39] Marbella was seized by the Nationalists with the aid of troops from Fascist Italy during the first months of the war, and became a haven for such prominent Nazis as Léon Degrelle and Wolfgang Jugler, and a favored getaway for the leisure and business of Falangist personalities like Jose Antonio Giron de Velasco[40] and Jose Banús, personal friends of the dictator Francisco Franco,[41] who were later responsible for the launching of urban development in Marbella in the 1960s. This urban expansion involved not only outsiders, but also local authorities and Nationalist leaders who had returned from exile, growth that came with the almost total opposition of the Republicans. [citation needed]

After World War II, Marbella was a small jasmine-lined village with only 900 inhabitants. Ricardo Soriano, Marquis of Ivanrey, moved to Marbella and popularised it among his rich and famous friends.[42] In 1943 he had acquired a country estate located between Marbella and San Pedro called El Rodeo, and later built a resort there called Venta y Albergues El Rodeo, beginning the development of tourism in Marbella.[43]

Soriano's nephew, Prince Alfonso of Hohenlohe-Langenburg, acquired another estate, Finca Santa Margarita, which in 1954 would become the Marbella Club, an international resort of movie stars, business executives and the nobility. Both these resorts would be frequented by members of European aristocratic families with well-recognised names: Bismarck, Rothschild, Thurn und Taxis, Metternich, de Mora y Aragon, de Salamanca or Thyssen-Bornemisza, transforming Marbella into a destination for the international jet set.[42]

Given Alfonso's maternal membership in Spain's titled aristocracy (his mother, María de la Piedad de Yturbe y Scholtz-Hersmendorff, was the Marquesa de Belvís de las Navas), and his paternal kinship to the royal courts of Europe, the hotel quickly proved to be popular with vacationing members of Europe's social elites for its casual but discreet luxury. Jaime de Mora y Aragón, a Spanish bon vivant and brother to Fabiola, Queen of the Belgians, as well as Adnan Khashoggi and Guenter Rottman, were frequent visitors.[44][45]

Typical was a gala held in August 1998 as a fundraiser at the Marbella Club for an AIDS relief NGO. Prince Alfonso presided, supported by the sons of his first marriage to Princess Ira von Fürstenberg, an Agnelli heiress who arrived with her own entourage; Princess Marie-Louise of Prussia (great-granddaughter of Kaiser Wilhelm II) who, with her husband Count Rudolf "Rudi" von Schönburg–Glauchau, would eventually take over the Marbella Club Hotel from Prince Alfonso; and socialite Countess Gunilla von Bismarck.[46]

In 1974, Prince Fahd arrived in the city after having broken the bank at the Casino of Montecarlo.[47] Until his death in 2005, he was a frequent and profligate guest at Marbella, where his retinue of over a thousand people spending petro-dollars was welcomed,[48] including the then-anonymous Osama bin Laden who visited on a number of occasions with his family between 1977 and 1988.[49]

In the 1980s, Marbella continued to be a destination for the jet set. However, the city was cast in an unflattering light in 1987 when Melodie Nakachian, the daughter of local billionaire philanthropist Raymond Nakachian and the Korean singer Kimera was kidnapped, focusing international media scrutiny on the city.[50]

In 1991, the builder and president of Atlético Madrid, Jesús Gil y Gil was elected by a wide majority as mayor of Marbella for his own party, the Independent Liberal Group (GIL in Spanish), having promised to fight petty crime and the declining prestige associated with the region. He employed actor Sean Connery as an international spokesman for the city; Connery later ended this relationship after Gil used his image in an election campaign.

The city also experimented with extensive building activity under Gil's administration—critics complained that this construction was often performed without regard for the existing urban plan; consequently new development plans were suspended by the Andalusian government. Something of a maverick, Gil despised town-hall formalities, instead ruling from his office at the Club Financiero. Gil was strongly criticised by Spain's major parties, the (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party and the People's Party), but not enough voters were persuaded to oust him and Spanish celebrities continued to spend summers there. Gil's political party, GIL, extended to other Costa del Sol towns like Estepona and even across the Strait of Gibraltar to the Spanish North African cities of Ceuta and Melilla.

This period resulted in a reappraisal of the city's finances but also brought investigations of corruption. Jesús Gil was finally forced to resign in 2002 after being jailed for diverting public funds for Atlético. He was succeeded by Julián Muñoz, a former waiter well known for being romantically involved with singer Isabel Pantoja; more than one hundred trials for corruption followed. Muñoz was overthrown by his own party which then elected Marisol Yagüe, a former secretary, as the new mayor. Muñoz and Gil took part in a scandalous debate on television where each accused the other of having robbed public funds.[51]

The situation exploded in March 2006 when Yagüe was jailed as the city stood near bankruptcy. According to unsubstantiated testimony, Muñoz and Yagüe were puppets in the hands of Antonio Roca, a councilman who got the job after failing in private business and gathering substantial wealth while working as a public servant. While Yagüe was in jail, the city council was run by Tomás Reñones, a former Atlético Madrid football player, who ended up in jail as well. On April 8, 2006, the Spanish government decided to suspend the council, the first time such a course of action was taken in Spanish democracy.[52]

After a short period of interim government, municipal elections were held in May 2007. The People's Party (PP) gained a majority with 16 out of the total of 26 councilors. The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) had 10 councilors, United Left (IU) had 1.[53] The Mayor is Maria Angeles Muñoz, leader of the People's Party in Marbella. In the municipal elections of May 2011 the PP won 15 seats, the PSOE 7, IU 2 with three independents elected.[54][55]

Landmarks and places of interest

Old Town (Casco Antiguo)

The old town of Marbella includes the ancient city walls and the two historical suburbs of the city, the Barrio Alto, which extends north, and the Barrio Nuevo, located to the east. The ancient walled city retains nearly the same layout as in the 16th century. Here is the Plaza de los Naranjos, an example of Castilian Renaissance design, its plan laid out in the heart of Old Town after the Christian reconquest.[56] Around the square are arranged three remarkable buildings: the town hall, built in 1568 by the Catholic Monarchs in Renaissance style, the Mayor's house, which combines Gothic and Renaissance elements in its façade, with a roof of Mudejar style and fresco murals inside, and the Chapel of Santiago, the oldest religious building in the city, built earlier than the square and not aligned with it, believed to date from the 15th century. Other buildings of interest in the centre are the Church of Santa María de la Encarnación, built in the Baroque style starting in 1618, the Casa del Roque, and the remains of the Arabic castle and defensive walls; also in the Renaissance style are the Capilla de San Juan de Dios (Chapel of St. John of God), the Hospital Real de la Misericordia (Royal Hospital of Mercy) and the Hospital Bazán which now houses the Museum of Contemporary Spanish Engravings.

One of the highlights of the Barrio Alto is the Ermita del Santo Cristo de la Vera Cruz (Hermitage of the Holy Christ of the True Cross), built in the 15th century and enlarged in the eighteenth century, which consists of a square tower with a roof covered by glazed ceramic tiles. The Barrio Alto is also known as the San Francisco neighborhood, after a Franciscan convent formerly located there. The so-called Nuevo Barrio (New Town), separated from the walled city by the Arroyo de la Represa, has no monumental buildings but retains its original layout and much of its character in the simple whitewashed houses with their tiled roofs and exposed wooden beams, orchards and small corrals.[57]

Historic Eixample

Between the old town and the sea in the historic area known as Eixample, there is a small botanical garden on Paseo de la Alameda, and a garden with fountains and a collection of ten sculptures by Salvador Dalí on the Avenida del Mar, which connects the old town with the beach. To the west of this road, passing the Faro de Marbella, is Constitution Park, which houses the auditorium of the same name and the Skol Apartments, designed in the Modernist style by the Spanish architect Manuel Jaén Albaitero.

The Golden Mile of Nueva Andalucia

The Golden Mile is actually a stretch of four miles (6.4 km) between Marbella and Puerto Banús, on which are located some of the most luxurious residences in Marbella, such as the Palace of King Fahd, as well as some landmark hotels,[58] among them the Melia Don Pepe, the Hotel Marbella Club and the Puente Romano Hotel.

Nueva Andalucía is an area that was developed during the tourism boom of the 1960s, where may be found the ruins of the Roman villa by the Rio Verde,[59] and El Ángel, where the land of the old forge works was converted to an agricultural colony, and the Botanical Gardens of El Ángel with gardens of three different styles, dating from the 8th century.

San Pedro de Alcántara

At the heart of San Pedro de Alcántara are two industrial buildings of the 19th century: the Trapiche de Guadaiza and the sugar mill, which now houses the Ingenio Cultural Center. The 19th-century heritage of San Pedro is also represented by two buildings of colonial style, the parish Church and the Villa of San Luis, residence of the Marqués del Duero. Next to San Pedro, near the mouth of the river Guadalmina, are some of the most important archaeological sites in Marbella: the early Christian Basílica de Vega del Mar, the vaulted Roman baths of Las Bóvedas (the Domes) and the eponymous watch tower of Torre de Las Bóvedas.[60] The important archaeological site of Cerro Colorado is located near Benahavis; it features a chronologically complex stratigraphy that begins in the 4th century BC within a Mastieno (ancient Iberian ethnicity of the Tartessian confederation) area, then a town identified as Punic, and finally a Roman settlement. A series of domestic structures built behind the city walls, and corresponding to these different stages of occupation recorded in the archaeological sequence of the site, characterise the settlement as being fortified. A hoard of three pots filled with silver coins of mostly Hispano-Carthaginian origin, and numerous pieces of precious metalwork, along with clippings and silver ingots, all dating from the 3rd century BC were found here.[61]

District of Las Chapas

In the eastern part of the municipality in the district of Las Chapas is the site of Rio Real, situated on a promontory near the mouth of the river of the same name. Here traces of Phoenician habitation dating to the early 7th century BC were discovered in excavations made during an archaeological expedition led by Pedro Sánchez in 1998.[59][62] Bronze Age utensils including plates, carinated bowls, lamps and other ceramics of Phoenician and indigenous Iberian types have been found, as well as a few Greek examples. There are two ancient watchtowers, the Torre Río Real (Royal River Tower) and the Torre Ladrones (Tower of Thieves). Among the notable tourist attractions is the residential complex Ciudad Residencial Tiempo Libre (Residential Leisure City),[63] an architectural ensemble of the Modernist movement, which has been a registered property of Bien de Interés Cultural (Heritage of Cultural Interest) since 2006.

Beaches

The 27 kilometres (17 miles) of coastline within the limits of Marbella is divided into twenty-four beaches with different features; however, due to expansion of the municipality, they are all now semi-urban. They generally have moderate surf, golden or dark sand ranging through fine, medium or coarse in texture, and some gravel. The occupancy rate is usually high to midrange, especially during the summer months, when tourist arrivals are highest. Amongst the various notable beaches are Artola beach, situated in the protected area of the Dunas de Artola, and Cabopino, one of the few nudist beaches in Marbella, near the port of Cabopino. The beaches of Venus and La Fontanilla are centrally located and very popular, and those of Puerto Banús and San Pedro Alcántara have been awarded the blue flag of the Foundation for Environmental Education[64] for compliance with its standards of water quality, safety, general services and environmental management.

Politics and administration

Political administration of the municipal government is run by the Ayuntamiento (City Hall), whose members are elected every four years. The electoral roll is composed of all residents registered in Marbella who are over age 18 and a citizen of Spain or one of the other member states of the European Union. The Spanish Law on the General Election sets the number of councilors elected according to the population of the municipality;[65] the Municipal Corporation of Marbella consists of 27 councilors.

From the first democratic elections after the adoption of the 1978 Spanish Constitution in 1979, and until 1991, all the mayors of Marbella were members of the El Partido Socialista Obrero Español (The Spanish Socialist Workers Party, or PSOE).[66] Between 1991 and 2006 Marbella was governed by the neo-conservative Grupo Independiente Liberal (Independent Liberal Group, or GIL), with Jesús Gil y Gil as its head, who after his arrival in office stayed in power by controversial methods. His style of government—characterised by "town planning on demand" for developers, market speculation, and predatory incursions on the environment,— led to accusations of corruption. In 1999 he was convicted of crimes of embezzlement of public funds and falsifying public documents.[67]

The Malaya Case

After Jesús Gil, the mayoralty was occupied by Julián Muñoz, who was expelled from office by a vote of no confidence after he fired Juan Antonio Roca, a planning consultant. Julián Muñoz is involved in about a hundred pending court cases. In 2003, after the censure motion that ousted Julián Muñoz, the mayoral chair was won by Marisol Yague, who was prosecuted in 2006 for corruption and imprisoned, but later released on bail. That year, after other members of the city council were detained under corruption allegations, the Spanish Senate unanimously approved the report of the General Commission of Autonomous Communities and decreed the dissolution of the Marbella city councill, perhaps the most unusual such action to ever occur in modern Spain. The investigation, known as the Malaya case, has resulted in the detention of twenty-four persons and the seizure of goods worth 2.4 million euros.[68] Today the term "Marbellan urbanism" is synonymous with corruption in government[69] and its legacy of environmental destruction and overcrowding, as shown by the figure of 30,000 illegal homes built in the town, and the lack of significant educational and health infrastructure.

Since 2007, and for the first time in the history of Marbellan politics, the City Hall has been governed by the Popular Party.

Symbols

The design of the coat of arms and the flag used by Marbella city hall has been the subject of controversy. According to some sources, GIL changed these symbols without any consensus or heraldic rigor, nor had they been vetted by the Junta de Andalucía, so that different factions claim the rehabilitation of the shield granted by the Catholic Monarchs to the city in 1493 and official recognition of a flag designed in accordance with prevailing standards of vexillology.

Economy

According to 2003 data, Marbella is amongst the municipalities ranking highest in household disposable income per capita in Andalusia, second to Mojácar and matched by four other municipalities, including its neighbor, Benahavís.

Its business sector consisted of 17,647 establishments in 2005, representing a total of 14.7% of the businesses in Malaga province, and showed greater dynamism than the provincial capital itself for growth over the period 1998-2004, when it grew 9% compared to the 2.4% growth rate of Málaga. Compared to the rest of Andalusia, the volume of production in Marbella is higher than that of most other municipalities with similar population, ranking even above the capitals of Almeria, Huelva and Jaen.

As in most cities of the Andalusian coast, Marbella's economy revolves around tertiary activities. The service sector accounts for 60% of employment, while trade accounts for almost 20%. The main branches of the service sector are hospitality, real estate and business services, which fact underscores the importance of tourism in the Marbella economy. Meanwhile, the construction, industrial and agriculture sectors account for 14.2%, 3.8% and 2.4% of employment respectively.

The number of business establishments in the service sector accounts for 87.5% of the total, those in construction account for 9.6%, and in industry, 2.9%. Of these companies, 89.5% have fewer than 5 employees and only 2.3% have a staff of at least 20 employees.

In 2008 a study by the Institute of Statistics of Andalusia (IEA) based on 14 variables (income, equipment, training, etc.), found Marbella was the Andalusian city with the best development of the general welfare and the highest quality of life. According to the results of the study, Marbella ranks highest in the number of private clinics, sports facilities and private schools.[70]

Transport

Cities on the coast are accessible by bus from Marbella, including Málaga, Estepona, Torremolinos, Fuengirola and Gibraltar. The area is also served by the A7 motorway; the closest airport is Málaga-Costa Del Sol.

Marine shipping

The four ports of Marbella are primarily recreational; although both Puerto Banús and the Puerto de la Bajadilla are permitted to dock cruise ships, neither operates regular service to other ports. The port of Bajadilla is also home to the fishermen's guild of Marbella and is used for the transport of goods.

Rail

Marbella is the most populous municipality in the Iberian Peninsula without a railway station in its territory, and is the only Spanish city of over 100,000 inhabitants not served by rail.[71]

An infrastructure project is underway for the construction of the Corridor of Costa del Sol rail system to connect Nerja, Málaga and Algeciras, possibly to include a high speed railway, with several stops planned for Marbella. Until then the nearest station is near Fuengirola, 27 km (17 miles) distant, further away is Málaga Maria Zambrano, located in Málaga city, 57 km (35 miles) away, and Ronda Station, also 57 km (35 miles).

Intercity bus

Most intercity bus services are operated by CTSA-Portillo, communicating with major urban centres of the Costa del Sol, including Málaga and its airport, and nearby towns in the interior (Benahavis, Ojen, Ronda), as well as the Campo including Gibraltar (La Linea and Algeciras), some of the major cities of Andalusia (Almería, Cádiz, Córdoba, Jerez, Granada, Jaen, Seville and Úbeda)[72] and Mérida in Extremadura. The central bus station has connections to other domestic destinations, Madrid, and Barcelona.

Taxis

There are always plenty of taxis available from Malaga airport or from the different taxi ranks along the Costa del Sol, it is without doubt the most comfortable way of travelling to your holiday destination, most of these taxis are clean and non smoking.

Marbella is not formally integrated into the Metropolitan Transportation Consortium Málaga area.

Media

Given the ethnic diversity of the city, Marbella's newspapers and magazines are published in several European languages, among which are La Tribuna de Marbella (Spanish), and Costa del Sol Nachrichten (in German). In addition, Diario Sur (Spanish) or Southern Journal (in English) and La Opinión de Málaga (Spanish) have editorial offices in the city. Among the magazines with the largest circulation are those dedicated to fashion and lifestyle, such as Absolute Marbella, Essential Magazine, The European Magazine, Transform Magazine (all in English), and Das Aktuelle Spanienmagazin (in German). Golf Andalusia and Golf Spain magazines, monthly Spanish-English bilingual magazines with a total circulation of 45,000 copies, are distributed throughout Spain.

Marbella has several local television stations, such as M95 Television, Summer TV and South Coast Television, and several digital news dailies including the Voice of Marbella and Journal of Marbella.

Culture

Besides the typical Andalusian cultural events, a variety of annual festivals are held in Marbella, mainly between June and October; other events are held sporadically. Festivals dedicated to music include the Marbella International Opera Festival held in August since 2001,[73] the Marbella Reggae Festival[74] in July, and the Marbella International Film Festival[75] in June at different locations around the city—amongst them the beach, aboard a boat or in Old Town. It also hosts the Marbella International Film Festival,[76] the Spanish Film Festival and the Festival of Independent Theatre.

To provide venues for these and other events, the city has cultural facilities both publicly and privately managed, such as the Auditorium of Constitution Park, the Ingenio Cultural Center, the Teatro Ciudad de Marbella or Black Box Theatre, among others. In addition, there is a music conservatory, a cinema club, and several movie theatres showing foreign films dubbed into Castilian.

The International Contemporary Art Fair I, also known as MARB ART, was held in Marbella in 2005, exhibiting works of photography, painting, sculpture and graphic design by over 500 artists; it has been held annually since at the Palace of Congresses. The following year the 2006 extension of the Ateneo de Málaga Marbella (Atheneum of Málaga Marbella) opened, dedicated to the development of artistic and cultural activities.

Amongst local cultural associations is the Cilniana Association, an organization dedicated to protecting and promoting the heritage of Marbella and neighboring towns, which publishes its own magazine. Since 2009 the city has been home to Marbella University,[77] the first private university in the province of Málaga and the only one in Andalusia where classes are taught in English.

Museums

- Contemporary Spanish Engraving Museum:[78] created in 1992, contains a collection of prints by twentieth-century artists such as Picasso, Miró, Dalí, Tàpies, Chillida and the El Paso Group (Rafael Canogar, Manolo Millares, Antonio Saura, Pablo Serrano, et al.) amongst others, as well as an exhibition hall dedicated to teaching engraving techniques.

- Museum Cortijo de Miraflores: in addition to the museum, the farm houses an exhibition hall and other cultural classrooms, amongst them the olive oil mill.[79]

- Bonsai Museum: opened in 1992, it has a collection of specimens on permanent display and others for sale, with an emphasis on its extensive collection of olive trees[80] and examples of species such as Ginkgo, Oxicedro, Pentafila Pino, and zelcoba, also pines, oaks, and other species.

- Ralli Museum, dedicated primarily to art in Latin America, it has sculptures by Dalí and Aristide Maillol and paintings by Dalí, Miró,[81] Chagall, Henry Moore, amongst others.

- Municipal Archaeological Collection: its collection consists of archaeological artefacts found in the municipality.[82]

- Mechanical Art Museum: a cultural center located in the 19th-century Barriada del Ingenio,[83] it contains sculptures made from second-hand car parts by Antonio Alonso.

Cuisine

The traditional cuisine of Marbella is that of the Malagueño coast and is based on seafood. The most typical dish is fried fish, using anchovies, mackerel, mullet or squid, amongst others. Gazpacho and garlic soup are very typical. Bakeries sell oil cakes, wine donuts, borrachuelos (aniseed rolls fried with a little wine and dipped into syrup), torrijas (similar to French toast) and churros (fritters). In addition to the traditional native cuisine, there are many restaurants in Marbella that serve food of the international, nouvelle, or fusion cuisines.[84]

Festivals

In June, the Fair and Fiesta of San Bernabe is celebrated to honour the patron saint of Marbella. For a week there are various activities and performances which are divided into two parts: Fair Day, which began in Old Town and is now held in the Avenida del Doctor Maíz Viñals, and Fair Night, which takes place in Arroyo Primero. In October the fair and festivals in honor of the patron saint of San Pedro Alcantara are celebrated, which also last a full week. The smaller Fair and Festivals of Nueva Andalucía celebrated in early October in Las Chapas and El Ángel are also popular.[85] Throughout the summer season (July to October) most barrios of Marbella have events organized by neighborhood associations to encourage cultural activities including: bullfights, musical performances, photo competitions and sporting events,. Among the best known associations are those of Santa Marta, Salto del Agua, Leganitos, Divina Pastora, Trapiche, Plaza de Toros and Miraflores. Other festivals and local celebrations include the Pilgrimages of Cruz de Juanar (May), La Virgen del Carmen (July), and La Virgen Madre (August), as well as the Día del Tostón (November), a traditional celebration which consists of going to the fields to roast chestnuts.[86]

Tourism

The city is especially popular with tourists from Northern Europe[87] (including the United Kingdom, Ireland and Germany) and also Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.[88] Marbella is particularly noted for the presence of aristocrats, celebrities and wealthy people;[89] it is a popular destination for luxury yachts,[90] and increasingly so for cruise ships, which dock in its harbour.[91][92]

The area is popular with golfers and boaters, and there are many private estates and luxury hotels in the vicinity, including the Marbella Club Hotel. Marbella hosts a WTA tennis tournament on red clay, the Andalucia Tennis Experience.

Sights in or near Marbella include:

- Arabian wall

- Bonsai museum

- Museo del Grabado Español Contemporáneo

- Old city centre

- Playa de la Bajadilla (beach)

- Playa de Fontanilla (beach)

- Puerto Banús, a marina built by José Banús where Rolls-Royces and Ferraris meet yachts.

- The Golden Mile featuring the Marbella Club Hotel and its beach club, as well as the late King Fahd's palace.

- Encarnation's Church (Iglesia de la Encarnación). Oldest church in the city situated in the old-town.

Notable residents

- George Clooney-actor

- Ousted Cuban president Fulgencio Batista died in Guadalmina, near Marbella, in 1973.

- Rick Parfitt OBE, legendary British rock musician from Status Quo, lives in the mountains just outside of Marbella.[93]

- Def Leppard stayed in a house in Marbella while recording parts of the Slang album.[94]

- Antonio Banderas, born in the nearby city of Málaga, has been a regular visitor to Marbella where he has a house in Los Monteros. Stella, his daughter with wife, US actress Melanie Griffith, was born in Marbella in 1999.

- In 1981 English actress Joan Collins accepted her career-making role in the hit prime time melodrama Dynasty while living in her Marbella vacation home.

- Sean Connery had a residence in Marbella from 1970 to 1998, where he was regularly seen playing golf when not filming.[95]

- English writer Vincent Cronin had a home in Marbella for decades and passed away there in 2011.

- Arms dealer Monzer al-Kassar was a longtime resident until his imprisonment, and has been nicknamed "The Prince of Marbella".

- Mark Langford, the former, multi-millionaire boss of The Accident Group who notoriously sacked most of his 2,700 staff by text message, died after being involved in a car accident in Marbella on April 11, 2007

- Actor Dolph Lundgren resides in Marbella and London with his wife and two children.

- English songwriter Richard Daniel Roman

- Porn star Linsey Dawn McKenzie

- Mike Reid, English actor and comedian, was living in Marbella at the time of his death on 29 July 2007. He was born in Hackney, London, and retired to Marbella a few years before he died.[96]

- Andy Gray, Scottish footballer

- Frank Harper, actor

- Jörg Wontorra, German sport journalist

- Santi Cazorla, footballer

- Ebi, Persian singer

- Joe Atlan, musician

- Julio Iglesias, singer

Media references

The short story Soñar un Crimen is set in Marbella. It details one of the infamous murders that occurred in the city.

Marbella was featured in the popular political thriller, Syriana. It was used as the location for a private party which an Arabian Emir hosts. Marbella was portrayed as an extremely affluent city with most cars at the entrance of the palace being very expensive. In the same year it appeared in Steven Spielberg's Munich in a very similar context.

In 2006, there was an international advertisement advertising Marbella as a tourist destination. The song on the advert is aptly called Marbella and is performed by singer Cristie.

Torrente 2: Misión en Marbella and the Finnish 1985 comedy film Uuno Epsanjassa is situated in Marbella.

Many other movies and TV programmes such as Nip/Tuck portray it as a playground for the rich.

ITV aired a TV programme in spring 2007 called Marbella Belles which portrays a series of British women who now live in Marbella with their rich partners.

Cast of Living On The Edge visit on the fourth episode of the first season.

It is also referenced in the stage play "Noises Off" by Michael Frayn. The character Phillip and his wife Belinda have been tax exiles in Spain. The character Gary thinks he and his guest are alone in the house, when he spots Phillip, and thinks he's a ghost. Gary: "Hold on a second, you're not from the other world!" Phillip: "Yes, yes, Marbella!"

Carlos Baute's song "Colgando en tus Manos" mentions him and his love vacationing in Marbella and Marta Sanchez sings this line in their duet version of the song.

The second half of series 2 of Auf Wiedersehen, Pet is set in Marbella.

The British TV show The Only Way Is Essex has filmed multiple times in Marbella, including the current series.

Twin towns - Sister cities

Marbella is twinned with:

|

See also

References

- ↑ La población andaluza. Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía. 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Archaeology Marbella". PGB España. Archived from the original on 29 June 20012. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marbella Museums and Art Galleries". World Guides. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "An up-and-coming cultural quarter for Marbella?". Déjà Vu Marbella. 19 November 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Costa del Sol Concerts for Summer 2012". i-Marbella.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marbella events and activities". Marbella Family Fun. Archived from the original on 29 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Reggaeville: World of Reggae in One Village". Reggaeville.

- ↑ "Marbella Opera Festival & Other August Events". Enforex Spanish Language School. Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Marbella: mapa geológico de España. Ministerio de Industria y Energía. 1978. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Teresa Moreno (Ph. D.) (2002). The Geology of Spain. Geological Society. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-86239-127-7. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Andrés Díez Herrero; Luis Laín Huerta; Miguel Llorente Isidro (2009). A handbook on flood hazard mapping methodologies. IGME. p. 23. ISBN 978-84-7840-813-9. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marbella Weather". World Weather Online. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Pilar Rodríguez Quirós (23 September 2007). "La Sierra de las Nieves crece mirando al mar". Diario Sur (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 25 October 2008. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ↑ Muñoz-Reinoso, José Carlos (6 May 2004). "Diversity of maritime juniper woodlands". Forest Ecology and Management 192 (2–3): 267–276. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2004.01.039.

- ↑ "Decapod crustacean assemblages from littoral bottoms of the Alborán Sea (Spain, west Mediterranean Sea): spatial and temporal variability". Scientia Marina (Institut de Ciències del Mar de Barcelona) 72 (3): 437–449. September 2008. ISSN 0214-8358. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

|coauthors=requires|author=(help) - ↑ "Population and Housing Census 2011. Municipal results Málaga". Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Retrieved 12 April 2013. "Results of database queries are ephemeral"

- ↑ "Censos de Población y Viviendas 2011. Resultados para Andalucía". Instituto de Estadistica y Cartografia de Andalucia. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ Chris Chaplow. "Population of Andalucia in 2011". andalucia.com. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ "Federación de Asociaciones de Vecinos de Marbella" (in Spanish). Federación de Asociaciones de Vecinos de Marbella. 29 September 2008. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ "Diccionario de la Lengua Española". Real Academia Española.

- ↑ Francisco Guillén Robles (1874). Historia de Málaga y su provincia. Rubio y Cano. p. 216. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Castro, J. L. L. (2009). "El poblamiento rural fenicio en el sur de la Península Ibérica entre los siglos VI a III aC". Gerión. Revista de Historia Antigua 26 (1): 149–182. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Anderson, James M. (1991). Spain: One Thousand One Sights: An Archaeological and Historical Guide. Michigan State University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-919813-93-9. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ Clifford Edmund Bosworth (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. p. 103. ISBN 978-90-04-15388-2. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Zozaya, Juan (1991). "Fortification building in al-Andalus". Madrider Beiträge (Kolloquium Berlin: Verlag Philipp von Zabern) 24 (Spanien under der Orient im frühen under hohen Mittelalte): 69. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ Jerrilynn Denise Dodds (1992). Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 70–71. ISBN 978-0-87099-636-8. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- ↑ Ibn Batuta (1 December 1996). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354. Asian Educational Services. p. 313. ISBN 978-81-206-0809-2. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/source/1354-ibnbattuta.html

- ↑ Víctor Gallero Galván. "Historia de Coín" (in Spanish). Junta de Andalucia Instituto de Educación Secundaria Los Montecillos. Archived from the original on 26 June 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ↑ United States. Congress. House (1879). House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents: 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress, 1st Session. p. 1050. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Chris Evans; Göran Rydén (2005). The Industrial Revolution In Iron: The Impact Of British Coal Technology In Nineteenth-Century Europe. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-7546-3390-7. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Aenaeus Bernardus Westerhof (1975). Genesis of magnetite ore near Marbella, southern Spain: formation by oxidation of silicates in polymetamorphic gedrite-bearing and other rocks. GUA. p. 13. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Joseph Harrison (1978). An Economic History of Modern Spain. Manchester University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-7190-0704-0. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Historia de San Pedro Alcántara Marqués del Duero". Ayuntamiento de Marbella Delegación de Comunicación. Archived from the original on April 27, 2012. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Great Britain. Parliament. House of Commons (1886). House of Commons Papers. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 344. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Gabriel Tortella Casares (2000). The Development of Modern Spain: An Economic History of the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Harvard University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-674-00094-0. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ José Bernal Gutierrez. "Comportamiento demográfico ante la inversión minera foránea. La población de Marbella en los inicios de la Marbella Iron Ore Company and Limited (1866-1874)" (in Spanish). Universidad de Granada. p. 16. Archived from the original on 19 May 2005. Retrieved 12 April 2013. "Footnote 94: "En la última década del siglo, la crisis industrial viene acompañada de los primeros síntomas del declive minero: en 1893 se suspendió la explotación por la gran acumulación de existencias, y se va haciendo reconocible, al mismo tiempo, la poca disposición que la sociedad propietaria de las minas de l término, la ‘Marbella Iron Ore C&L’, demostró para renovar los sistemas tradicionales de extracción, y que a la postre redundaría en el paulatino agotamiento de las vetas” ( Vid LÓPEZ SERRANO, F. A. (2000): “Miseria, guerra y corrupción. Una aproximación a la Marbella de 1898", Cilniana , 13, pp. 4-17)"

- ↑ Enrique Navarro Jurado (2003). Puede seguir creciendo la Costa del Sol?: indicadores de saturación de un destino turístico. Servicio de Publicaciones, Diputación Provincial de Málaga. p. 29. ISBN 978-84-7785-585-9. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ Lucía Prieto Borrego (2007). "Mujer y Anticlericalismo: La Justicia Militar en Marbella 1937–1939". HAOL (in Spanish) (Asociación de Historia Actual) 12 (Winter): 102. ISSN 1696-2060. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Redacción (27 November 2008). "Retiran el título de Hijo Predilecto al creador de la Seguridad Social y el derecho al cobro de desempleo". Minuto Digital. Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ "Puerto Banús and Nueva Andalucía". Essential Marbella Magazine. 29 March 2012. Archived from the original on 19 March 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2013.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Localizacion de Marbella Informacion sobre Marbella que pertenece a la provincia de Málaga" (in Spanish). La web del ayuntamiento. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Ángel A. Jordán (1 April 1989). Marbella Story. GeoPlaneta, Editorial, S. A. p. 73. ISBN 978-84-320-4707-7. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Count Rudi von Schönburg (6 October 2009). "The Beginnings of Marbella Club". Panorama. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Ronald Kessler (1987). Khashoggi: the rise and fall of the world's richest man. Corgi. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-552-13060-8. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Mary Costelow (2 July 2012). "Count Rudi keeps the luxury Marbella Club hotel eternally young". Girlahead. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Antonio Montilla (8 August 2005). "La vida de Fahd en la Milla de Oro" (in Spanish). ABC Gente / Estilo. Archived from the original on 17 June 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Ghosts of Spain: Travels Through Spain and Its Silent Past. Walker. 4 March 2008. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-8027-1674-3. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ "Graceless ending for Marbella spa". The Olive Press. 4 April 2012. Archived from the original on 14 November 2012.

- ↑ Paul Delaney (21 November 1987). "Raid by Police Frees Kidnapped Girl, 5, in Spain". New York Times. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Spain's politics: The man from Marbella". The Economist. 21 August 2003. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Daniel González Herrera, (16 November 2006). "Marbella awaits new elections after most local politicians are accused of corruption". City Mayors. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Gestión Municipal". Concejales (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Marbella. 4 April 2010. Archived from the original on 4 April 2010. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ "Elecciones Locales 2011". Concejales a elegir en 2011 (Councilors to be elected in 2011) (in Spanish). Gobierno de España, Ministerio del Interior. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ local election results, Spanish Ministry of the Interior, accessed 17 July 2011

- ↑ George Hazel; Roger Parry (2004). Making cities work. Wiley-Academy. pp. 75–77. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ "Trazado cartesiano de sus antiguas calles" (in Spanish). 14 June 2011. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011.

- ↑ Mona King (2000). Essential Costa del Sol. AA Publishing. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7495-2371-8. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Christopher Wawn; David Wood (2000). In search of Andalucia: a historical geographical observation of the Málaga sea board. Pentland. p. 228. ISBN 978-1-85821-690-4. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ United States. Hydrographic Office (1916). Mediterranean Pilot: Strait of Gibraltar, south and southeast coast of Spain, African coast from Cape Spartel to Gulf of Gabes-including the Balearic Islands. Hydrographic Office under the authority of the secretary of the navy. p. 140. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ Salvador Bravo Jiménez, Miguel Vila Oblitas, Rafael Dorado Cantero, Antonio Soto Iborra (2009). "El tesoro de Cerro Colorado. La Segunda Guerra Púnica en la costa occidental malagueña (Benahavís, Málaga)_". In Alicia Arévalo González. Actas XIII congreso nacional de numismática: "Moneda y arqueologia : Cádiz, 22-24 de octubre de 2007 (in Spanish) 1. Madrid: Universidad de Cádiz. pp. 105–118. ISBN 978-84-89157-42-2. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ↑ Peter Alexander René van Dommelen; Carlos Gómez Bellard; Roald F. Docter (2008). Rural Landscapes of the Punic World. Isd. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-84553-270-3. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- ↑ Javier Navarro Luna (1999). Territorio y administraciones públicas en Andalucía. Universidad de Sevilla. p. 180. ISBN 978-84-472-0501-1. Retrieved 29 January 2013.

- ↑ "Playas de Marbella". Webmalaga.com. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ "Ley Orgánica 5/1985, de 19 de junio, del Régimen Electoral General". Boletín Oficial del Estado. Gobierno de España, Ministero de la Presidencia. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Ayuntamientos". Ayuntamiento de Marbella. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Causas contra Gil y sus encarcelamientos". El Mundo. 14 May 2004. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ Daniel González Herrera (16 November 2006). "Marbella awaits new elections after most local politicians are accused of corruption". City Mayors. City Mayors Foundation. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2013.

- ↑ "La disputa por Marbella". El Siglo de Europa. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Un estudio de la Junta sitúa a Marbella como el municipio andaluz con mayor calidad de vida". SUR, diario de Málaga. 19 April 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marbella, única urbe española de más de cien mil habitantes sin servicio de tren". Málaga Hoy. 17 November 2008. Archived from the original on 18 June 2010. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ "Horario de Autobuses Marbella". Corporación Española de Transporte (CTSA) Portrillo. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 21 April 2013.

- ↑ "El Teatro ‘Ciudad de Marbella’ acogerá del 8 al 11 el XI Festival Internacional de Ópera de Marbella". Ayuntamiento de Marbella. 30 July 2012. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "Presentación del Marbella Reggae Festival". 16 April 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Jazz Journal International. Billboard Limited. 2004. p. 18. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- ↑ "Curtain set to rise on Marbella International Film Festival". Euro Weekly News. 27 September 2012. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marbella University: English-Speaking for Pioneering Business and Psychology". Marbella University. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "Spanish Contemporary Engraving Museum". What to do in Marbella. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "Museo Cortijo Miraflores" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Marbella. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Museo del Bonsai". Costa del Sol. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Ralli Museum in Marbella". Ralli Museums. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Sede de la Delegación de Cultura / Colección arqueológica" (in Spanish). Ayuntamiento de Marbella. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "The Sugar Refinery". PGB. Archived from the original on 29 June 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Food in Marbella". Marbella Guide. 26 November 2009. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ "Fiestas de Marbella". webmalaga.com. Sociedad de Planificación y Desarrollo SOPDE. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ "Festivals in Marbella". Marbella Guide. Archived from the original on 2 October 2012. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- ↑ Myra Shackley (23 May 2012). Atlas of Travel and Tourism Development. Routledge. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-136-42782-4. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Conal Urquhart (9 March 2013). "How the influx of new global elites is changing the face of Europe". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 March 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Ken Bernstein (1990). Spain. Berlitz. p. 182. ISBN 978-2-8315-0494-0. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ Berlitz Guides (1 January 1993). Berlitz Travellers Guide: Spain 1993. Berlitz International, Incorporated. p. 775. ISBN 978-2-8315-1783-4. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "Marbella renueva su apuesta por los cruceros pese a la incertidumbre sobre La Bajadilla". Diario Sur (in Spanish). 5 February 2013. "Responsables turísticos de la ciudad cierran en Fitur dos acuerdos para colocar al municipio en el mapa de las compañías de lujo que trabajan en el sector"

- ↑ Fairplay. Fairplay Publications Limited. July 1997. p. 169. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ "By John Dingwall Status Quo rocker Rick Parfitt swaps his wild days for family life". Daily Record. 26 December 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- ↑ http://www.defleppard.com/albums/slang

- ↑ Michael Feeney Callan (31 October 2012). Sean Connery. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7535-4706-9. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ "Reid's widow: He was my rock". The Sun. 2007-10-04. Retrieved 2012-02-22.

- ↑ "Batumi - Twin Towns & Sister Cities". Batumi City Hall. Archived from the original on 2012-05-04. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marbella. |

- Ayuntamiento de Marbella — official Marbella city hall site, partly in English, mostly in Spanish

Marbella travel guide from Wikivoyage

Marbella travel guide from Wikivoyage

| |||||||||||||

| |||||

.svg.png)