Mandala

Mandala (Sanskrit: मण्डल Maṇḍala, 'circle') is a spiritual and ritual symbol in Hinduism and Buddhism, representing the Universe.[1] The basic form of most mandalas is a square with four gates containing a circle with a center point. Each gate is in the general shape of a T.[2][3] Mandalas often exhibit radial balance.[4]

The term is of Hindu origin. It appears in the Rig Veda as the name of the sections of the work, but is also used in other Indian religions, particularly Buddhism.

In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of aspirants and adepts, as a spiritual teaching tool, for establishing a sacred space, and as an aid to meditation and trance induction.

In common use, mandala has become a generic term for any plan, chart or geometric pattern that represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically; a microcosm of the universe.

Hinduism

Religious meaning

A yantra is a two- or three-dimensional geometric composition used in sadhanas, or meditative rituals. It is thought to be the abode of the deity. Each yantra is unique and calls the deity into the presence of the practitioner through the elaborate symbolic geometric designs. According to one scholar, "Yantras function as revelatory symbols of cosmic truths and as instructional charts of the spiritual aspect of human experience"[5]

Many situate yantras as central focus points for Hindu tantric practice.Yantras are not representations, but are lived, experiential, nondual realities. As Khanna describes:

Despite its cosmic meanings a yantra is a reality lived. Because of the relationship that exists in the Tantras between the outer world (the macrocosm) and man’s inner world (the microcosm), every symbol in a yantra is ambivalently resonant in inner–outer synthesis, and is associated with the subtle body and aspects of human consciousness.[6]

Political meaning

The "Rajamandala" (or "Raja-mandala"; circle of states) was formulated by the Indian author Kautilya in his work on politics, the Arthashastra (written between 4th century BC and 2nd century AD). It describes circles of friendly and enemy states surrounding the king's state.[7]

In historical, social and political sense, the term "mandala" is also employed to denote traditional Southeast Asian political formations (such as federation of kingdoms or vassalized states). It was adopted by 20th century Western historians from ancient Indian political discourse as a means of avoiding the term 'state' in the conventional sense. Not only did Southeast Asian polities not conform to Chinese and European views of a territorially defined state with fixed borders and a bureaucratic apparatus, but they diverged considerably in the opposite direction: the polity was defined by its centre rather than its boundaries, and it could be composed of numerous other tributary polities without undergoing administrative integration.[8] Empires such as Bagan, Ayutthaya, Champa, Khmer, Srivijaya and Majapahit are known as "mandala" in this sense.

Buddhism

_embracing_his_consort_Vajra_Vetali%2C_in_the_corners_are_the_Red%2C_Green_White_and_Yellow_Yamari.jpg)

Early and Theravada Buddhism

The mandala can be found in the form of the Stupa[9] and in the Atanatiya Sutta[10] in the Digha Nikaya, part of the Pali Canon. This text is frequently chanted.

Tibetan Vajrayana

In the Tibetan branch of Vajrayana Buddhism, mandalas have been developed into sandpainting. They are also a key part of Anuttarayoga Tantra meditation practices.

Visualisation of Vajrayana teachings

The mandala can be shown to represent in visual form the core essence of the Vajrayana teachings. The mind is "a microcosm representing various divine powers at work in the universe."[11] The mandala represents the nature of experience, and the intricacies of both the enlightened and confused mind.

While on the one hand, the mandala is regarded as a place separated and protected from the ever-changing and impure outer world of samsara,[12] and is thus seen as a "Buddhafield"[13] or a place of Nirvana and peace, the view of Vajrayana Buddhism sees the greatest protection from samsara being the power to see samsaric confusion as the "shadow" of purity (which then points towards it).

Mount Meru

A mandala can also represent the entire universe, which is traditionally depicted with Mount Meru as the axis mundi in the center, surrounded by the continents.[14]

Wisdom and impermanence

In the mandala, the outer circle of fire usually symbolises wisdom. The ring of eight charnel grounds[15] represents the Buddhist exhortation to be always mindful of death, and the impermanence with which samsara is suffused: "such locations were utilized in order to confront and to realize the transient nature of life."[16] Described elsewhere: "within a flaming rainbow nimbus and encircled by a black ring of dorjes, the major outer ring depicts the eight great charnel grounds, to emphasize the dangerous nature of human life."[17] Inside these rings lie the walls of the mandala palace itself, specifically a place populated by deities and Buddhas.

Five Buddhas

One well-known type of mandala is the mandala of the "Five Buddhas", archetypal Buddha forms embodying various aspects of enlightenment. Such Buddhas are depicted depending on the school of Buddhism, and even the specific purpose of the mandala. A common mandala of this type is that of the Five Wisdom Buddhas (a.k.a. Five Jinas), the Buddhas Vairocana, Aksobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amoghasiddhi. When paired with another mandala depicting the Five Wisdom Kings, this forms the Mandala of the Two Realms.

Practice

Mandalas are commonly used by tantric Buddhists as an aid to meditation.

The mandala is "a support for the meditating person",[18] something to be repeatedly contemplated to the point of saturation, such that the image of the mandala becomes fully internalised in even the minutest detail and can then be summoned and contemplated at will as a clear and vivid visualized image. With every mandala comes what Tucci calls "its associated liturgy [...] contained in texts known as tantras",[19] instructing practitioners on how the mandala should be drawn, built and visualised, and indicating the mantras to be recited during its ritual use.

By visualizing "pure lands", one learns to understand experience itself as pure, and as the abode of enlightenment. The protection that we need, in this view, is from our own minds, as much as from external sources of confusion. In many tantric mandalas, this aspect of separation and protection from the outer samsaric world is depicted by "the four outer circles: the purifying fire of wisdom, the vajra circle, the circle with the eight tombs, the lotus circle."[18] The ring of vajras forms a connected fence-like arrangement running around the perimeter of the outer mandala circle.[20]

As a meditation on impermanence (a central teaching of Buddhism), after days or weeks of creating the intricate pattern of a sand mandala, the sand is brushed together into a pile and spilled into a body of running water to spread the blessings of the mandala.

Kværne[21] in his extended discussion of sahaja, discusses the relationship of sadhana interiority and exteriority in relation to mandala thus:

...external ritual and internal sadhana form an indistinguishable whole, and this unity finds its most pregnant expression in the form of the mandala, the sacred enclosure consisting of concentric squares and circles drawn on the ground and representing that adamant plane of being on which the aspirant to Buddha hood wishes to establish himself. The unfolding of the tantric ritual depends on the mandala; and where a material mandala is not employed, the adept proceeds to construct one mentally in the course of his meditation." [22]

Offerings

A "mandala offering"[23] in Tibetan Buddhism is a symbolic offering of the entire universe. Every intricate detail of these mandalas is fixed in the tradition and has specific symbolic meanings, often on more than one level.

Whereas the above mandala represents the pure surroundings of a Buddha, this mandala represents the universe. This type of mandala is used for the mandala-offerings, during which one symbolically offers the universe to the Buddhas or to one's teacher. Within Vajrayana practice, 100,000 of these mandala offerings (to create merit) can be part of the preliminary practices before a student even begins actual tantric practices.[24] This mandala is generally structured according to the model of the universe as taught in a Buddhist classic text the Abhidharma-kośa, with Mount Meru at the centre, surrounded by the continents, oceans and mountains, etc.

Shingon Buddhism

The Japanese branch of Mahayana Buddhism -- Shingon Buddhism—makes frequent use of mandalas in its rituals as well, though the actual mandalas differ. When Shingon's founder, Kukai, returned from his training in China, he brought back two mandalas that became central to Shingon ritual: the Mandala of the Womb Realm and the Mandala of the Diamond Realm.

These two mandalas are engaged in the abhiseka initiation rituals for new Shingon students, more commonly known as the Kechien Kanjō (結縁灌頂). A common feature of this ritual is to blindfold the new initiate and to have them throw a flower upon either mandala. Where the flower lands assists in the determination of which tutelary deity the initiate should follow.

Sand mandalas, as found in Tibetan Buddhism, are not practiced in Shingon Buddhism.

Nichiren Buddhism

The Mandala in Nichiren Buddhism is called a moji-mandala (文字曼陀羅) and is a paper hanging scroll or wooden tablet whose inscription consists of Chinese characters and medieval-Sanskrit script representing elements of the Buddha's enlightenment, protective Buddhist deities, and certain Buddhist concepts. Called the Gohonzon, it was originally inscribed by Nichiren, the founder of this branch of Japanese Buddhism, during the late 13th Century. The Gohonzon is the primary object of veneration in some Nichiren schools and the only one in others, which consider it to be the supreme object of worship as the embodiment of the supreme Dharma and Nichiren's inner enlightenment. The seven characters Nam Myoho Renge Kyo, considered to be the name of the supreme Dharma, as well as the invocation that believers chant, are written down the center of all Nichiren-sect Gohonzons, whose appearance may otherwise vary depending on the particular school and other factors.

Pure Land Buddhism

Mandalas have sometimes been used in Pure Land Buddhism to graphically represent Pure Lands, based on descriptions found in the Larger Sutra and the Contemplation Sutra. The most famous mandala in Japan is the Taima Mandala, dated to approximately 763 CE. The Taima Mandala is based upon the Contemplation Sutra, but other similar mandalas have been made subsequently. Unlike mandalas used in Vajrayana Buddhism, it is not used as an object of meditation or for esoteric ritual. Instead, it provides a visual representation of the Pure Land texts, and is used as a teaching aid.[citation needed]

Also in Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, Shinran and his descendant, Rennyo, sought a way to create easily accessible objects of reverence for the lower-classes of Japanese society. Shinran designed a mandala using a hanging scroll, and the words of the nembutsu (南無阿彌陀佛) written vertically. This style of mandala is still used by some Jodo Shinshu Buddhists in home altars, or butsudan.

Christianity

Forms which are evocative of mandalas are prevalent in Christianity: the celtic cross; the rosary; the halo; the aureole; oculi; the Crown of Thorns; rose windows; the Rosy Cross; and the dromenon on the floor of Chartres Cathedral. The dromenon represents a journey from the outer world to the inner sacred centre where the Divine is found.[25]

Similarly, many of the Illuminations of Hildegard von Bingen can be used as mandalas, as well as many of the images of esoteric Christianity, as in Christian Hermeticism, Christian Alchemy, and Rosicrucianism.

Western psychological interpretations

According to art therapist and mental health counselor Susanne F. Fincher, we owe the re-introduction of mandalas into modern Western thought to Carl Jung, the Swiss psychoanalyst. In his pioneering exploration of the unconscious through his own art making, Jung observed the motif of the circle spontaneously appearing. The circle drawings reflected his inner state at that moment. Familiarity with the philosophical writings of India prompted Jung to adopt the word "mandala" to describe these circle drawings he and his patients made. In his autobiography "Memories, Dreams, Reflections," Jung wrote:

"I sketched every morning in a notebook a small circular drawing,...which seemed to correspond to my inner situation at the time....Only gradually did I discover what the mandala really is:...the Self, the wholeness of the personality, which if all goes well is harmonious." pp 195 – 196.

Jung recognized that the urge to make mandalas emerges during moments of intense personal growth. Their appearance indicates a profound re-balancing process is underway in the psyche. The result of the process is a more complex and better integrated personality. As Jungian analyst Marie Louise von Franz explains:

"The mandala serves a conservative purpose—namely, to restore a previously existing order. But it also serves the creative purpose of giving expression and form to something that does not yet exist, something new and unique….The process is that of the ascending spiral, which grows upward while simultaneously returning again and again to the same point.[26]

Creating mandalas helps stabilize, integrate, and re-order inner life.[27]

According to the psychologist David Fontana, its symbolic nature can help one "to access progressively deeper levels of the unconscious, ultimately assisting the meditator to experience a mystical sense of oneness with the ultimate unity from which the cosmos in all its manifold forms arises."[28]

Gallery

-

A diagramic drawing of the Sri Yantra, showing the outside square, with four T-shaped gates, and the central circle.

-

Vishnu Mandala

-

Painted 19th century Tibetan mandala of the Naropa tradition, Vajrayogini stands in the center of two crossed red triangles, Rubin Museum of Art

-

Painted Bhutanese Medicine Buddha mandala with the goddess Prajnaparamita in center, 19th century, Rubin Museum of Art

-

Sand mandala tibet 1.JPG

Tibetan monks making a temporary sand mandala in the City-Hall of Kitzbühel in Austria in 2002.

-

Mandala of the Six Chakravartins

-

Vajravarahi Mandala

-

Kalachakra Mandala

-

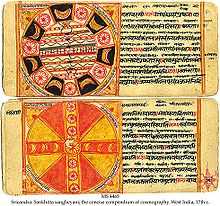

Jain cosmological diagrams and text.

-

A mandala near the entrance to Tawang Monastery.

-

Mandala painted by a patient of Carl Jung

-

A modern mandala

See also

- Architectural drawing

- Astrological symbols

- Bhavachakra

- Chakra

- Chi

- Dharmachakra

- Form constant

- Ganachakra

- Great chain of being

- Life energy

- Magic

- Manna

- Namkha

- Quincunx

- Quintessence

- Sacred art

- Sand mandala

- Yantra

References

- ↑ "mandala". Merriam–Webster Online Dictionary. 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ Artiste Nomade, What's a mandala?

- ↑ Kheper,The Buddhist Mandala - Sacred Geometry and Art

- ↑ www.sbctc.edu (adapted). "Module 4: The Artistic Principles". Saylor.org. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Khanna Madhu, Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity. Thames and Hudson, 1979, p. 12.

- ↑ Khanna, Madhu, Yantra: The Tantric Symbol of Cosmic Unity. Thames and Hudson, 1979, pp. 12-22

- ↑ Singh, Prof. Mahendra Prasad (2011). Indian Political Thought: Themes and Thinkers. Pearson Education India. ISBN 8131758516. pp. 11-13.

- ↑ Dellios, Rosita (2003-01-01). "Mandala: from sacred origins to sovereign affairs in traditional Southeast Asia". Bond University Australia. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- ↑ Prebish & Keown, Introducing Buddhism, ebook, Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 2005; printed edn, Routledge, 2006; page 89

- ↑ Skilling, Mahasutras, volume II, parts I & II, Pali Text Society, pages 553ff

- ↑ John Ankerberg, John Weldon, Encyclopedia of New Age Beliefs: The New Age Movement, p. 343

- ↑ Sudden or Gradual Enlightenment

- ↑ Ngondro

- ↑ Mipham (2000) pp. 65,80

- ↑ A Monograph on a Vajrayogini Thanka Painting

- ↑ Charnel Grounds

- ↑ http://www.sootze.com/tibet/mandala.htm

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Mandala

- ↑ The Mandala in Tibet

- ↑ Mandala

- ↑ Per Kvaerne 1975: p. 164

- ↑ Kvaerne, Per (1975). "On the Concept of Sahaja in Indian Buddhist Tantric Literature". (NB: article first published in Temenos XI (1975): pp.88-135). Cited in: Williams, Jane (2005). Buddhism: Critical Concepts in Religious Studies, Volume 6. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33226-5, ISBN 978-0-415-33226-2. Source: (accessed; Friday April 16, 2010)

- ↑ The Meaning and Use of a Mandala

- ↑ Preliminary Practice (Ngondro)

- ↑ See David Fontana: "Meditating with Mandalas", p. 11, 54, 118

- ↑ C. G. Jung: "Man and His Symbols," p. 225

- ↑ see Susanne F. Fincher: "Creating Mandalas: For Insight, Healing, and Self-Expression," p. 1 - 18

- ↑ See David Fontana: "Meditating with Mandalas", p. 10

Sources

- Brauen, M. (1997). The Mandala, Sacred circle in Tibetan Buddhism Serindia Press, London.

- Bucknell, Roderick & Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. Curzon Press: London. ISBN 0-312-82540-4

- Cammann, S. (1950). Suggested Origin of the Tibetan Mandala Paintings The Art Quarterly, Vol. 8, Detroit.

- Cowen, Painton (2005). The Rose Window, London and New York, (offers the most complete overview of the evolution and meaning of the form, accompanied by hundreds of colour illustrations.)

- Crossman, Sylvie and Barou, Jean-Pierre (1995). Tibetan Mandala, Art & Practice The Wheel of Time, Konecky and Konecky.

- Fontana, David (2005). "Meditating with Mandalas", Duncan Baird Publishers, London.

- Gold, Peter (1994). Navajo & Tibetan sacred wisdom: the circle of the spirit. ISBN 0-89281-411-X. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions International.

- Mipham, Sakyong Jamgön (2002) 2000 Seminary Transcripts Book 1 Vajradhatu Publications ISBN 1-55055-002-0

- Tucci,Giuseppe (1973). The Theory and Practice of the Mandala trans. Alan Houghton Brodrick, New York, Samuel Weisner.

- Vitali, Roberto (1990). Early Temples of Central Tibet London, Serindia Publications.

- Wayman, Alex (1973). "Symbolism of the Mandala Palace" in The Buddhist Tantras Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass.

- Chris Bell (n.d.). The Maṇḍala

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mandalas. |

- Introduction to Mandalas

- Expnation of Vajradhatu Mandala by Dharmapala Thangka Centre

- Berzin, Alexander (2003). The Berzin Archives. The Meaning and Use of a Mandala.

- Mandalaweb.info - Documents, researches and interviews about Mandalas

- Mandalas in the Tradition of the Dalai Lamas' Namgyal Monastery by Losang Samten

- Information on creating and interpreting mandalas

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||