Maliseet people

| Aboriginal peoples in Canada |

|---|

.JPG) |

|

History

|

|

Politics |

|

Culture

|

|

Demographics

|

|

Linguistics

|

|

Religions

|

|

Index

|

|

Wikiprojects Portal

WikiProject

First Nations Inuit Métis |

The Wolastoqiyik, or Maliseet (English pronunciation: /ˈmæləˌsiːt/,[1] also spelled Malecite), are an Algonquian-speaking Native American/First Nations/Aboriginal people of the Wabanaki Confederacy. They are the Indigenous people of the Saint John River valley and its tributaries, crossing the borders of New Brunswick and Quebec in Canada, and Maine in the United States. Today Maliseet people have also migrated to other parts of the world. The Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians are the federally recognized tribe of Maliseet people in the United States.

Name

Although generally known in English as the Maliseet or Malecite, their name for themselves, or autonym, is Wolastoqiyik. They are known in French as Malécites or Étchemins (the latter collectively referring to the Maliseet and Passamaquoddy, both Eastern Algonquian-speaking groups.)

They called themselves Wolastoqiyik after the Wolastoq River at the heart of their territory. (In English it is commonly known as the St. John River.) Wolastoq means "Beautiful River". Wolastoqiyik means "People of the Beautiful River," in Maliseet.[2]

The term Maliseet is the exonym by which the Mi'kmaq people referred to this group when speaking about them to early Europeans. Maliseet or Malesse'jik was a Mi'kmaq word meaning "broken talkers", "lazy speakers" or "he speaks badly".[3] Although the Wolastoqiyik and Mi'kmaq languages are closely related, the name expressed what the Mi'kmaq perceived as a sufficiently different dialect to be called a "broken" version of their own language. The Europeans met the Mi'kmaq before the next Algonquian people, and adopted their term for the Wolastoqiyik.

History

First Encounters

At the time of European encounter, the Wolastoqiyik were living in walled villages and practicing horticulture (corn, beans, squash and tobacco) In addition to growing crops they subsisted from fishing, hunting and gathering fruits, berries, nuts and natural produce. While written accounts in the early 17th century such as those of Samuel de Champlain and Marc LesCarbot reference a large village at the mouth of the St. John River, sources from later in the century indicate their headquarters had shifted to Meductic, on the middle reaches of the St. John River.

The French explorers were the first to establish a fur trade with them that became important through their territory. Some European goods were desired because they were useful to Wolastoqiyik subsistence and culture. The French Jesuits also established missions where some Wolastoqiyik converted to Catholicism. With years of colonialism many learned the French language. The French called them Malecite, adapting the name they had been told by other tribes. Maliseet (Malecite) have long been associated with the Saint John River in New Brunswick and Maine, and early extended as far as the St Lawrence. These Algonkian (Algonquian) speakers referred to themselves as Wolastoqiyik ("of the beautiful river"). Their lands and resources are bounded on the east by Micmac, on the west by Passamaquoddy and Penobscot. Local histories depict many encounters with Iroquois and Montagnais. Contact with European fisher-traders in the early 17th century and with specialized fur traders developed into a stable relationship which lasted for nearly 100 years. Despite devastating population losses to European diseases, these Atlantic hunters held on to coastal or river locations for hunting, fishing and gathering, and concentrated along river valleys for trapping.

The European Colonizers

The lucrative eastern fur trade faltered with the general unrest as European hostilities concentrated between Québec and Port-Royal, and as increasing sporadic fighting and raiding took place on the lower Saint John (English against the French). Maliseet women took over a larger share of the economic burden and began to farm, raising crops which previously had been grown only south of Maliseet territory. Men continued to hunt, though with limited success, but they proved useful to the French as support against the English, and for a short period during the late 17th and early 18th centuries Maliseet men became virtually a military organization.

With the gradual cessation of hostilities in the first quarter of the 18th century, and with the beaver supply severely diminished, there was little possibility of a return to traditional ways of life. Traditional Aboriginal agriculture on the river was curtailed by the coming of European settlers. All the farmland along the Saint John River, previously occupied by Maliseet, was taken, leaving many Aboriginal people displaced.

The Nineteenth Century

The Maliseet practiced some traditional crafts as late as the 19th century, especially building wigwams and birchbark canoes, but major shifts had taken place during the previous two centuries as Maliseet acquired European metal cutting tools and containers, muskets and alcohol, foods and clothing. In making wood, bark or basketry items, or in guiding, trapping and hunting, the Maliseet speak of themselves as engaged in "Indian work." The growth of potato farming in Maine and New Brunswick created a market for Maliseet baskets and containers. Other Maliseet work in pulp mills, construction, nursing, teaching and business. With evidence of widespread hunger and wandering, pressure came to bear on government officials who established the first Indian reserves at Oromocto, Fredericton, Kingsclear, Woodstock and Tobique.

Into Modern Times

The Maliseet of New Brunswick experienced problems of unemployment and poverty common to Aboriginal people elsewhere in Canada, but they have evolved a sophisticated and intricate system of decision making and resource allocation, especially at Tobique where they support community enterprises in economic development, scouting and sports. Some are successful in middle and higher education and have important trade and professional standings; individuals and families are prominent in Aboriginal and women's rights; and others serve in provincial and federal native organizations, in government and in community development. There were 4659 registered Maliseet in 1996.

Culture

The customs and language of the Maliseet are very similar to those of the neighboring Passamaquoddy (or Peskotomuhkati). They are also close to those of the Mi'kmaq and Penobscot tribes.

The Wolastoqiyik differed from the Mi'kmaq by pursing a partial agrarian economy. They also overlapped territory with neighboring peoples. The Wolastoqiyik and Passamaquoddy languages are similar enough that linguists consider them slightly different dialects of the same language. Typically they are not differentiated for study.

Two traditional Maliseet songs - a dance song and a love song - were collected by Natalie Curtis and published in 1907.[4] As transcribed by Curtis, the love song demonstrates a meter cycle of seven bars and switches between major and minor tonality.[5]

Current situation

Today, within New Brunswick, approximately 3,000 Maliseet live within the Madawaska, Tobique, Woodstock, Kingsclear, Saint Mary's and Oromocto First Nations. There are also 600 in the Houlton Band in Maine and 1200 in the Viger First Nation in Quebec. An unknown number of 'off-reserve' Wolastoqiyik live in other parts of the world.

About 650 native speakers of Maliseet remain, and about 500 of Passamaquoddy, living on both sides of the border between New Brunswick and Maine. Most are older, although some young people have begun studying and preserving the language. An active program of scholarship on the Maliseet-Passamaquoddy language takes place at the Mi'kmaq - Maliseet Institute at the University of New Brunswick, in collaboration with the native speakers. David Francis Sr., a Passamaquoddy elder living in Sipayik, Maine, has been an important resource for the program. The Institute has the goal of helping Native American students master their native languages. The linguist Philip LeSourd has done extensive research on the language.

The Houlton Band of Maliseets was given a nonvoting seat in the Maine Legislature, starting with the 126th Legislature in 2013. The first holder of the seat is Henry John Bear.[6]

Surnames associated with Maliseet ancestry include: Sabattis, Gabriel, Saulis, Jenniss, Atwin, Launière, Athanase, Nicholas, Brière, Bear, Ginnish, Solis, Vaillancourt, Wallace, Paul, Polchies, Tomah, Sappier, Perley, Aubin, Francis, Sacobie, Nash, Meuse. Also included are DeVoe, DesVaux, DeVou, DeVost, DeVot, DeVeau.

Notable Maliseet

- Sandra Lovelace Nicholas, a Maliseet activist, is known for challenging discriminatory provisions of the Indian Act in Canada, which deprived Aboriginal or Indigenous women of their status when they married non-Aboriginals. It imposed a patriarchal idea of descent and identity on peoples who traditionally had matrilineal systems, whereby children belonged to the mother's people. Nicholas was instrumental in bringing the case before the United Nations Human Rights Commission and lobbying for the 1985 legislation which reinstated some rights of First Nation women and their children in Canada via Bill C31. Retaining status for future generations is still an issue for Maliseet and all Aboriginal groups. Nicholas was appointed to the Canadian Senate September 21, 2005 [7]

- Graydon Nicholas was named the Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick, Canada, in September 2009, a Viceregal position in which he acts as the Queen's representative in the province.

- Peter Lewis Paul was a Maliseet oral historian (1902-1989) who lived on the Woodstock Reserve (N.B.) on the banks of the St. John River. Raised by his grandfather Newell Polchies, and known as Wapeyit piyel, he became a fountain of traditional knowledge and generously shared information with numerous professional linguists, ethnohistorians, and anthropologists. The recipient of many honors, he was awarded a Centennial Medal in 1969, received an honorary Doctor of Law degree from the University of New Brunswick, and the Order of Canada in 1987.[8]

- Gabriel Acquin was the founder of the Reserve created in 1867, which is now part of St. Mary's First Nation.

- David Slagger represented the Maliseet people as their first tribal representative to the Maine House of Representatives

- Brenda Perley became the first woman chief to ever be elected within Tobique First Nations.

References

- ↑ Erickson, Vincent O. (1978). "Maliseet-Passamaquoddy." In Northeast, ed. Bruce G. Trigger. Vol. 15 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, pg. 123.

- ↑ LeSourd, Philip, ed. 2007. Tales from Maliseet Country: the Maliseet texts of Karl V. Teeter, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, p. 17, fnote 4

- ↑ Erickson 1978, pg. 135

- ↑ Natalie Curtis (1907). The Indians' Book: an offering by the American Indians of Indian lore, musical and narrative, to form a record of the songs and legends of their race. New York and London: Harper and Brothers Publishers.

- ↑ Clint Goss (2013). "Maliseet Love Song". Flutopedia. Retrieved 2013-11-22.

- ↑ Bayly, Julia (January 26, 2012). "King will caucus with Senate Democrats". Bangor Daily News.

- ↑ http://www.liberal.ca/senators_e.aspx?id=15916

- ↑ Karl V. Teeter, ed. 1993. In Memoriam Peter Lewis Paul 1902-1989.Canadian Ethnology Service, Mercury Series Paper 126. Hull: Canadian Museum of Civilization

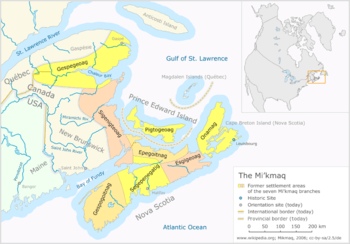

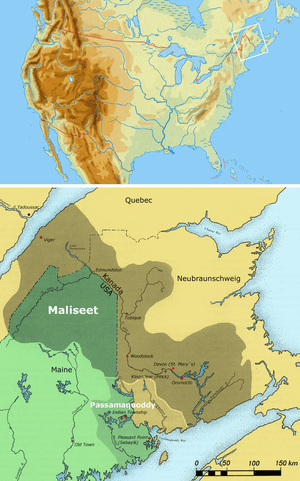

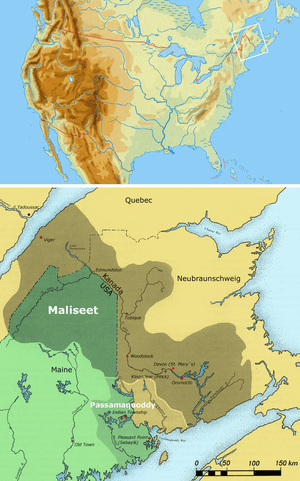

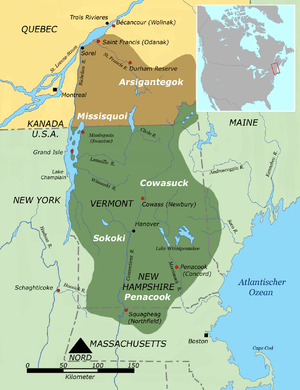

Maps

Maps showing the approximate locations of areas occupied by members of the Wabanaki Confederacy (from north to south):

-

Maliseet, Passamaquoddy

-

Eastern Abenaki (Penobscot, Kennebec, Arosaguntacook, Pigwacket/Pequawket)

-

Western Abenaki (Arsigantegok, Missisquoi, Cowasuck, Sokoki, Pennacook)

External links

- Maliseet language and culture links

- Mi'kmaq-Maliseet Institute - University of New Brunswick

- Passamaquoddy-Maliseet Language Portal

"Maliseet Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Maliseet Indians". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.