Malik Ayaz

The Sultan is to the right, shaking the hand of the sheykh, with Ayaz standing behind him. The figure to his right is Shah Abbas I who reigned about 600 years later.

Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, Tehran

Malik Ayaz, son of Aymáq Abu'n-Najm, was a Turkish slave of Georgian origin[1][2] who rose to the rank of officer and general in the army of Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni (also known as Mahmud Ghaznavi). His rise to power was a reward for the devotion he bore his master.

In 1021, the Sultan raised Ayaz to kingship, awarding him the throne of Lahore, which the Sultan had taken after a long siege and a fierce battle in which the city was torched and depopulated. As the first Muslim governor of Lahore, he rebuilt and repopulated the city. He also added many important features, such as a masonry fort, which he built in the period of 1037-1040 on the ruins of the previous one, demolished in the fighting, and city gates (as recorded by Munshi Sujan Rae Bhandari, author of the Khulasatut Tawarikh (1596 C.E.). The present Lahore Fort is built in the same location. Under his rulership the city became a cultural and academic center, renowned for poetry.

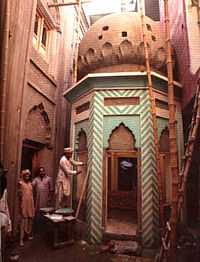

The tomb of Malik Ayaz can still be seen in the Rang Mahal commercial area of town.

Road named after Ayaz in Pakistan

There is a road bearing the name of Ayaz in the city of Gujar Khan, Pakistan. The road name is Hayatsar Road. Hayatsar was initially known as Ayazsar before being renamed as Hayatsar. It is believed that Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi ordered Ayaz to choose an area for the accommodation of soldiers before war with Rajput. Ayaz chosen land, which is now called Gujar Khan.

From Six poems by Farid al-Din 'Attar; Southern Iran, 1472;

British Library, London

Notes

- ↑ Allsen, Thomas. The Royal Hunt in Eurasian History. p. 264.

- ↑ Pearson, Michael Naylor. Merchants and Rulers in Gujarat: The Response to the Portuguese in the Sixteenth Century. p. 67.