Magnoliids

| Magnoliids | |

|---|---|

| |

| Flower of Asimina triloba | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Magnoliids |

| Orders | |

Magnoliids (or Magnoliidae) are a group of about 9,000[1] species of flowering plants, including magnolias, nutmeg, bay laurel, cinnamon, avocado, black pepper, tulip tree and many others. They are characterized by trimerous flowers, pollen with one pore, and usually branching-veined leaves.

Classification

Traditionally, Magnoliidae is the botanical name of a subclass. The circumscription of a subclass will vary with the taxonomic system being used. The only requirement is that it must include the family Magnoliaceae.[2] More recently, the group has been redefined under the PhyloCode as a node-based clade comprising the Canellales, Laurales, Magnoliales, and Piperales.

APG system

The APG III (2009) and its predecessor systems do not use formal botanical names above the rank of order. Under these systems, larger clades are usually referred to by informal names, such as "magnoliids" (plural, not capitalized) or "magnoliid complex". The APG III recognizes a clade within the angiosperms for the magnoliids. The circumscription is:

clade magnoliids

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The current phylogeny and composition of the magnoliids.[3][4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The clade includes most of the basal groups of the angiosperms. This clade was formally named Magnoliidae in 2007 under provisions of the PhyloCode.[5]

Cronquist system

The Cronquist system (1981) used the name Magnoliidae for one of six subclasses (within class Magnoliopsida = dicotyledons). In the original version of this system the circumscription was:[6]

- subclass Magnoliidae :

- order Magnoliales

- order Laurales

- order Piperales

- order Aristolochiales

- order Illiciales

- order Nymphaeales

- order Ranunculales

- order Papaverales

Dahlgren and Thorne systems

Both Dahlgren and Thorne classified the magnoliids (sensu APG) in superorder Magnolianae, rather than as a subclass.[7] In their systems, the name Magnoliidae is used for a much larger group including all dicotyledons. This is also the case in some of the systems derived from the Cronquist system.

Dahlgren divided his Magnolianae into ten orders, more than other systems of the time, and unlike Cronquist and Thorne, he did not include the Piperales.[8] Thorne grouped most of his Magnolianae into two large orders, Magnoliales and Berberidales, although his Magnoliales was divided into suborders along lines similar to the ordinal groupings used by both Cronquist and Dahlgren. Thorne revised his system in 2000, restricting the name Magnoliidae to include only the Magnolianae, Nymphaeanae, and Rafflesianae, and removing the Berberidales and other previously included groups to his subclass Ranunculidae.[9] This revised system diverges from the Cronquist system, but agrees more closely with the circumscription later published under APG II.

Comparison table

Comparison of classification systems is often difficult. Two authors may apply the same name to groups with different composition of members; for example, Dahlgren's Magnoliidae includes all dicots, whereas Cronquists' Magnoliidae is only one of five dicot groups. Two authors may also describe the same group with nearly identical composition, but each may then apply a different name to that group or place the group at a different taxonomic rank. For example, the composition of Cronquist's subclass Magnoliidae is nearly the same as Thorne's (1992) superorder Magnolianae, despite the difference in taxonomic rank.

Because of these difficulties and others, the synoptic table below imprecisely compares the definition of "magnoliid" groups in the systems of four authors. For each system, only orders are named in the table. All orders included by a particular author are listed and linked in that column. When a taxon is not included by that author, but was included by an author in another column, that item appears in unlinked italics and indicates remote placement. The sequence of each system has been altered from its publication in order to pair corresponding taxa between columns.

| APG II system[10] magnoliids |

Cronquist system[6] Magnoliidae |

Dahlgren system[8] Magnolianae |

Thorne system (1992)[7] Magnolianae |

Thorne system (2000)[9] Magnolianae |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Laurales | Laurales | Laurales | Magnoliales | Magnoliales |

| Magnoliales | Magnoliales | Magnoliales | ||

| Annonales | ||||

| Canellales | Winterales | |||

| Piperales | Lactoridales | |||

| Aristolochiales | Aristolochiales | |||

| Piperales | Piperales in Nymphaeanae | |||

| unplaced or in basal clades | Chloranthales | |||

| Illiciales | Illiciales | |||

| in Rosidae | Rafflesiales | in Rafflesianae | in Rafflesianae | |

| Nymphaeales | in Nymphaeanae | in Nymphaeanae | in Nymphaeanae | |

| Ceratophyllales | in Ranunculidae | |||

| placed in eudicot clade | Nelumbonales | Nelumbonales | ||

| Ranunculales | in Ranunculanae | Berberidales | ||

| Papaverales | ||||

| in Dilleniidae | in Theanae | Paeoniales |

Economic uses

The magnoliids is a large group of plants, with many species that are economically important as food, drugs, perfumes, timber, and as ornamentals, among many other uses.

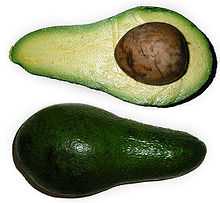

One widely cultivated magnoliid fruit is the avocado (Persea americana), which is believed to have been cultivated in Mexico and Central America for nearly 10,000 years.[11] Now grown throughout the American tropics, it probably originates from the Chiapas region of Mexico or Guatemala, where "wild" avocados may still be found.[12] The soft pulp of the fruit is eaten fresh or mashed into guacamole. The ancient peoples of Central America were also the first to cultivate several fruit-bearing species of Annona.[6] These include the custard-apple (A. reticulata), soursop (A. muricata), sweetsop or sugar-apple (A. squamosa), and the cherimoya (A. cherimola). Both soursop and sweetsop now are widely grown for their fruits in the Old World as well.[13]

Some members of the magnoliids have served as important food additives. Oil of sassafras was formerly used as a key flavoring in both root beer and in sarsaparilla.[14] The primary ingredient responsible for the oil's flavor is safrole, but it is no longer used in either the United States or Canada. Both nations banned the use of safrole as a food additive in 1960 as a result of studies that demonstrated safrole promoted liver damage and tumors in mice.[15] Consumption of more than a minute quantity of the oil causes nausea, vomiting, hallucinations, and shallow rapid breathing. It is very toxic, and can severely damage the kidneys.[16] In addition to its former use as a food additive, safrole from either Sassafras or Ocotea cymbarum is also the primary precursor for synthesis of MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine), commonly known as the drug ecstasy.[17]

Other magnoliids also are known for their narcotic, hallucinogenic, or paralytic properties. The Polynesian beverage kava is fermented from the pulverized roots of Piper methysticum, and has both sedative and narcotic properties.[13] It is used throughout the Pacific in social gatherings or after work to relax. Likewise, some native peoples of the Amazon take a hallucinogenic snuff made from the dried and powdered fluid exuded from the bark of Virola trees.[6] Another hallucinogenic compound, myristicin, comes from the spice nutmeg.[18] As with safrole, ingestion of nutmeg in quantities can lead to hallucinations, nausea, and vomiting, with symptoms lasting several days.[19] A more severe reaction comes from poisoning by rodiasine and demethylrodiasine, the active ingredients in fruit extract from Chlorocardium venenosum. These chemicals paralyze muscles and nerves, resulting in tetanus-like reactions in animals. The Cofán peoples of westernmost Amazon in Colombia and Ecuador use the compound as a poison to tip their arrows in hunting.[20]

Not all the effects of chemical compounds in the magnoliids are detrimental. In previous centuries, sailors would use Winter's Bark from the South American tree Drimys winteri to ward off the vitamin-deficieny of scurvy.[13] Today, benzoyl is extracted from Lindera benzoin (common spicebush) for use as a food additive and skin medicine, due to its anti-bacterial and anti-fungal properties.[21] Drugs extracted from the bark of Magnolia have long been used in traditional Chinese medicine. Scientific investigation of magnolol and honokiol have shown promise for their use in dental health. Both compounds demonstrate effective anti-bacterial activity against the bacteria responsible for bad breath and dental caries.[22][23] Several members of the family Annonaceae are also under investigation for uses of a group of chemicals called acetogenins. The first acetogenin discovered was uvaricin, which has anti-leukemic properties when used in living organisms. Other acetogenins have been discovered with anti-malarial and anti-tumor properties, and some even inhibit HIV replication in laboratory studies.[24]

Many magnoliid species produce essential oils in their leaves, bark, or wood. The tree Virola surinamensis (Brazilian "nutmeg") contains trimyristin, which is extracted in the form of a fat and used in soaps and candles, as well as in shortenings.[25] Other fragrant volatile oils are extracted from Aniba rosaeodora (bois-de-rose oil), Cinnamomum porrectum, Cinnamomum cassia, and Litsea odorifera for scenting soaps.[26] Perfumes also are made from some of these oils; ylang-ylang comes from the flowers of Cananga odorata, and is used by Arab and Swahili women.[13] A compound called nutmeg butter is produced from the same tree as the spice of that name, but the sweet-smelling "butter" is used in perfumery or as a lubricant rather than as a food.

Magnoliids are also important sources of spices and herbs used to flavor food, including the spices black pepper, cinnamon and nutmeg, and the herb bay laurel.

See also

References

- ↑ Jeffrey D. Palmer, Douglas E. Soltis and Mark W. Chase (2004). "The plant tree of life: an overview and some points of view". American Journal of Botany 91 (10): 1437–1445 (Fig.2). doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1437. PMID 21652302.

- ↑ ICBN, Art. 16

- ↑ The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 161: 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x.

- ↑ Soltis, P. S.; D. E. Soltis (2004). "The origin and diversification of Angiosperms". American Journal of Botany 91 (10): 1614–1626. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1614. PMID 21652312.

- ↑ Cantino, Philip D.; James A. Doyle, Sean W. Graham, Walter S. Judd, Richard G. Olmstead, Douglas E. Soltis, Pamela S. Soltis, & Michael J. Donoghue (2007). "Towards a phylogenetic nomenclature of Tracheophyta". Taxon 56 (3): E1–E44.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Cronquist, Arthur (1981). An Integrated System of Classification of Flowering Plants. New York: Columbia Univ. Press. ISBN 0-231-03880-1.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Thorne, R. F. (1992). "Classification and geography of the flowering plants". Botanical Review 58: 225–348. doi:10.1007/BF02858611.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Dahlgren, R.M.T. (1980). "A revised system of classification of angiosperms". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 80 (2): 91–124. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1980.tb01661.x.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Thorne, R. F. (2000). "The classification and geography of the flowering plants: Dicotyledons of the class Angiospermae". Botanical Review 66 (4): 441–647. doi:10.1007/BF02869011.

- ↑ Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2003). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society 141: 399–436. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x.

- ↑ "Angiosperms". The New Encyclopaedia Britannica 13. 1994. pp. 634–645.

- ↑ Kopp, Lucille E. (1966). "A taxonomic revision of the genus Persea in the Western Hemisphere. (Persea-Lauraceae)". Memoirs of the New York Botanical Garden 14 (1): 1–117.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Heywood, V. H. (ed.) (1993). Flowering Plants of the World (updated ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 27–42. ISBN 0-19-521037-9.

- ↑ Hester, R. E.; Roy M. Harrison (2001). Food safety and food quality. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. p118. ISBN 0-85404-270-9.

- ↑ Hayes, Andrew Wallace (2001). Principles and Methods of Toxicology (4th ed.). CRC Press. pp. p518. ISBN 1-56032-814-2.

- ↑ "Sassafras oil overdose". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ↑ "MDMA and MDA producers using Ocotea cymbarum as a precursor". Microgram Bulletin. XXXVIII (11). 2005.

- ↑ Shulgin, Alexander T. (1966-04-23). "Possible implication of myristicin as a psychotropic substance". Nature 210 (5034): 380–384. doi:10.1038/210380a0. PMID 5336379.

- ↑ Panayotopoulos, D. J.; D. D. Chisholm (1970). "Hallucinogenic effect of nutmeg". British Medical Journal 1 (5698): 754. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.5698.754-b. PMC 1699804. PMID 5440555.

- ↑ Kostermans, A. J.; Homer V. Pinkley, William L Stern (1969). "A new Amazonian arrow poison: Ocotea venenosa". Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University 22 (7): 241–252.

- ↑ Zomlefer, Wendy B. (1994). Guide to Flowering Plant Families. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 29–39. ISBN 0-8078-2160-8.

- ↑ Greenberg, M; P. Urnezis, M. Tian (2007). "Compressed mints and chewing gum containing magnolia bark extract are effective against bacteria responsible for oral malodor". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 55 (23): 9465–9469. doi:10.1021/jf072122h. PMID 17949053.

- ↑ Chang, B; Lee Y, Ku Y, Bae K, Chung C. (1998). "Antimicrobial activity of magnolol and honokiol against periodontopathic microorganisms". Planta Medica 64 (4): 367–369. doi:10.1055/s-2006-957453. PMID 9619121.

- ↑ Pilar Rauter, Amélia; A. F. Dos Santos and A. E. G. Santana (2002). "Toxicity of Some species of Annona Toward Artemia Salina Leach and Biomphalaria Glabrata Say". Natural Products in the New Millennium: Prospects and Industrial Application. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 540 pages. ISBN 1-4020-1047-8. Retrieved 2008-07-12.

- ↑ Pereira Pinto, Gerson (1951). "Contribuição ao estudo químico do Sêbo de Ucuúba". Boletim Técnico do Instituto Agronômico do Norte 23: 1–63.

- ↑ Kostermans, A. J. G. H. (1957). "Lauraceae". Communication of the Forest Research Institute, Indonesia 57: 1–64.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Magnoliids |

|