Magnetoelectric effect

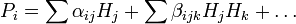

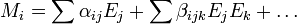

The magnetoelectric (ME) effect is the phenomenon of inducing magnetic (electric) polarization by applying an external electric (magnetic) field. The effects can be linear or/and non-linear with respect to the external fields. In general, this effect depends on temperature. The effect can be expressed in the following form

where P is the electric polarization, M the magnetization, E and H the electric and magnetic field, and α and β are the linear and nonlinear ME susceptibilities. The effect can be observed in single phase and composite materials. Some examples of single phase magnetoelectrics are Cr2O3,[1] and multiferroics materials which show a coupling between the magnetic and electric order parameters. Composite magnetoelectrics are combinations of magnetostrictive and electrostrictive materials, such as ferromagnetic and piezoelectric materials. The size of the effect depends on the microscopic mechanism. In single phase magnetoelectrics the effect can be due to the coupling of magnetic and electric orders as observed in some multiferroics. In composite materials the effect originates from interface coupling effects, such as strain. Some of the promising applications of the ME effect are sensitive detection of magnetic fields, advanced logic devices and tunable microwave filters.[1]

The SI-Unit of α is [s/m] which can be converted to the practical unit [V/(cm Oe)] by [s/m]=1.1 x10−11 εr [V/(cm Oe)]. For the CGS unit, [unitless] = 3 x 108 [s/m]/(4 x π)

History of the magnetoelectric effect

The magnetoelectric effect was first conjectured by P. Curie[2] in 1894 while the term "magnetoelectric" was coined by P. Debye[3] in 1926. A more rigorous prediction of a linear coupling between electric polarization and magnetization was shortly formulated by L.D. Landau and E. Lifshitz in one book of their famous series on theoretical physics.[4] Only in 1959, I. Dzyaloshinskii,[5] using an elegant symmetry argument, derived the form of a linear magnetoelectric coupling in Cr2O3. The experimental confirmation came just few months later when the effect was observed for the first time by D. Astrov.[6] The general excitement which followed the measurement of the linear magnetoelectric effect lead to the organization of the series of MEIPIC (Magnetoelectric Interaction Phenomena in Crystals) conferences. Between the prediction of I. Dzialoshinskii and the MEIPIC first edition (1973) more than 80 linear magnetoelectric compounds were found. Recently, technological and theoretical progress triggered a renaissance of these studies and magnetoelectric effect is still heavily investigated.

Origin of the magnetoelectric effect

Single-ion anisotropy

In crystals, spin-orbit coupling is responsible for single-ion magnetocrystalline anisotropies (provide link) which determine preferential axes for the orientation of the spins (such as easy axes). An external electric field may change the local symmetry seen by magnetic ions and affect both the strength of the anisotropy and the direction of the easy axes. Thus, single-ion anisotropy can couple an external electric field to spins of magnetically ordered compounds.

Symmetric Exchange striction

The main interaction between spins of transition metal ions in solids is usually provided by superexchange. This interaction depends on details of the crystal structure such as the bond length between magnetic ions and the angle formed by the bonds between magnetic and ligand ions. Symmetric exchange can be both positive and negative and is the main responsible of magnetic ordering. As the strength of symmetric exchange depends on the relative position of the ions, it couples spins to collective lattice distortions, called phonons. Coupling of spins to collective distortion with a net electric dipole can happen if the magnetic order breaks inversion symmetry. Thus, symmetric exchange can provide a handle to control magnetic properties through an external electric field.

Strain driven magnetoelectric heterostructured effect

Because materials exist that couple strain to electrical polarization (piezoelectrics, electrostrictives, and ferroelectrics) and that couple strain to magnetization (magnetostrictive/magnetoelastic/ferromagnetic materials), it is possible to couple magnetic and electric properties indirectly by creating composites of these materials that are tightly bonded so that strains transfer from one to the other.

Thin film strategy enables achievement of interfacial multiferroic coupling through a mechanical channel in heterostructures consisting of a magnetoelastic and a piezoelectric component.[7] This type of heterostructure is composed of an epitaxial magnetoelastic thin film grown on a piezoelectric substrate. For this system, application of a magnetic field will induce a change in the dimension of the magnetoelastic film. This process, called magnetostriction, will alter residual strain conditions in the magnetoelastic film, which can be transferred through the interface to the piezoelectric substrate. Consequently a polarization is introduced in the substrate through the piezoelectric process. The overall effect is that the polarization of the ferroelectric substrate is manipulated by an application of a magnetic field, which is the desired magnetoelectric effect (the reverse is also possible). In this case, the interface plays an important role in mediating the responses from one component to another, realizing the magnetoelectric coupling.[8] For an efficient coupling, a high-quality interface with optimal strain state is desired. In light of this interest, advanced deposition techniques have been applied to synthesize these types of thin film heterostructures. Molecular beam epitaxy has been demonstrated to be capable of depositing structures consisting of piezoelectric and magnetostrictive components. Materials systems studied included cobalt ferrite, magnetite, SrTiO3, BaTiO3, PMNT.[9][10][11]

Flexomagnetoelectric effect

Magnetically driven ferroelectricity is also caused by inhomogeneous[12] magnetoelectric interaction. This effect appears due to the coupling between inhomogeneous order parameters. It was also called as flexomagnetoelectric effect.[13] Usually it is describing using the Lifshitz invariant (i.e. single-constant coupling term).[14] It was shown that in general case of cubic hexoctahedral crystal the four phenomenological constants approach is correct.[15] The flexomagnetoelectric effect appears in spiral multiferroics[16] or micromagnetic structures like domain walls[17] and magnetic vortexes.[18] [19] Ferroelectricity developed from micromagnetic structure can appear in any magnetic material even in centrosymmetric one.[20] Building of symmetry classification of domain walls leads to determination of the type of electric polarization rotation in volume of any magnetic domain wall. Existing symmetry classification[21] of magnetic domain walls was applied for predictions of electric polarization spatial distribution in their volumes.[22][23] The predictions for almost all symmetry groups conform with phenomenology in which inhomogeneous magnetization couples with homogeneous polarization. The total synergy between symmetry and phenomenology theory appears if energy terms with electrical polarization spatial derivatives are taking into account.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 C. W. Nan et al., J. App. Phys. 103, 031101 (2008)

- ↑ P. Curie J. Physique, 3i`eme s'erie III (1894)

- ↑ P. Debye Z. Phys. 36, 300 (1926)

- ↑ L. Landau & E. Lifshitz "Electrodynamics of continuous media" Pergamon press

- ↑ I. Dzyaloshinskii Zh. Exp. Teor. Fiz. 37, 881 (1960)

- ↑ D. Astrov Sov. Phys. JETP 11, 708 (1960)

- ↑ G. Srinivasan, et al, Physical Review B, vol. 65, Apr 2002.

- ↑ J. F. Scott, Nature Mater. 6, 256 (2007).

- ↑ S. Xie, J. Cheng, et al, App. Phys Lett, vol. 93, pp. 181901-181903, Nov 2008

- ↑ M. Bibes, A. Barthélémy, Nature Mater. 7, 425 (2008)

- ↑ J. J. Yang, Y.G. Zhao, et al, Applied Physics Letters,vol. 94, May 2009.

- ↑ V.G. Bar'yakhtar, V.A. L'vov, D.A. Yablonskiy, JETP Lett. 37, 12 (1983) 673-675

- ↑ A.P. Pyatakov, A.K. Zvezdin, Eur. Phys. J. B 71 (2009) 419.

- ↑ M. Mostovoy, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96 (2006) 067601.

- ↑ B.M. Tanygin, On the free energy of the flexomagnetoelectric interactions, Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials, Volume 323, Issue 14 (2011) Pages 1899-1902

- ↑ T. Kimura, T. Goto, H. Shintani, K. Ishizaka, T. Arima, Y. Tokura, Nature 426 (2003) 55

- ↑ A.S. Logginov, G.A. Meshkov, A.V. Nikolaev, E.P. Nikolaeva, A.P. Pyatakov, A.K. Zvezdin, Applied Physics Letters 93 (2008) 182510

- ↑ A. P. Pyatakov, G. A. Meshkov, arXiv:1001.0391 [cond-mat.mtrl-sci]

- ↑ A. P. Pyatakov, G. A. Meshkov,A.K. Zvezdin, Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials 324 (2012) 3551

- ↑ I. Dzyaloshinskii, EPL 83 (2008) 67001

- ↑ V. Baryakhtar, V. L’vov, D. Yablonsky, Sov. Phys. JETP 60(5) (1984) 1072-1080

- ↑ V.G. Bar'yakhtar, V.A. L'vov, D.A. Yablonskiy, Theory of electric polarization of domain boundaries in magnetically ordered crystals, in: A. M. Prokhorov, A. S. Prokhorov (Eds.), Problems in solid-state physics, Chapter 2, Mir Publishers, Moscow, 1984, pp. 56-80

- ↑ B.M. Tanygin, JMMM, 323, 5 (2011) 616-619

- ↑ B.M. Tanygin, IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 15 (2010) 012073.