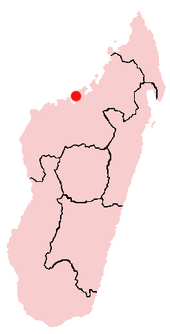

Maevarano Formation

| Maevarano Formation Stratigraphic range: Maastrichtian, 70-65.8 Ma ago[1] | |

|---|---|

| Type | Geological formation |

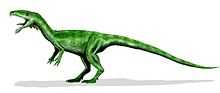

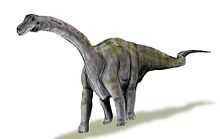

The Maevarano Formation is an Upper Cretaceous sedimentary rock formation found in the Mahajanga Province of northwestern Madagascar. It is most likely Maastrichtian in age, and records a seasonal, semiarid environment with rivers that had greatly varying discharges. Notable animal fossils recovered include the theropod dinosaur Majungasaurus, the early bird Vorona, the flying dromaeosaur Rahonavis, the titanosaurian sauropod Rapetosaurus, and the giant frog Beelzebufo.

Description

The Maevarano Formation is well-exposed in the Mahajanga Basin, in particular near the village of Berivotra near the northwestern coast of the island where its outcrops have been heavily dissected by erosion. At the time it was being deposited, its latitude was between 30°S and 25°S as Madagascar drifted northward after splitting from India about 88 million years ago. It is composed of three smaller units or members. The lowest is the Masorobe Member, which is usually reddish and is at least 80 meters thick (262 ft). Its rocks are mostly poorly-sorted coarse-grained sandstones with some finer-grained beds. It is separated by an erosional disconformity from the next member, the Anembalemba Member. The lower portion of the Anembalemba Member is fine to coarse clay-rich sandstone, whitish or light grey in color, with cross-bedding. The upper portion of this member is made of poorly-sorted clay-rich sandstone, light olive-grey in color, that lacks cross-bedding. Most vertebrate fossils come from the Anembalemba Member, especially from the upper portion. The Miadana Member, the third and uppermost member, is not always present, and is up to 25 meters thick (82 ft); in some places. Elsewhere, it is replaced by the marine Berivotra Formation. The Miadana Member is made up of claystone, siltstone, and sandstone, lacks cross-bedding, and has several colors of rock. The Maevarano Formation as a whole is underlain by the Marovoay beds and capped by the Berivotra Formation.[1]

The age of the Maevarano Formation has been debated; the Berivotra Formation, which is partially contemporaneous with the upper portions of the formation, shows that at least the upper part of the Maevarano is Maastrichtian in age. There is no evidence that it is Campanian,[1] despite previous reports to that effect.[2] The Berivotra Formation appears to include near its top a magnetic reversal, interpreted as the shift from Chron 30N to Chron 29R, which occurred approximately 65.8 million years ago (about 300 000 years before the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary and associated Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. This suggests that Maevarano organisms also lived shortly before (geologically speaking) the extinction event.[1]

History of exploration

The Maevarano Formation was first explored by French military physician Dr. Félix Salètes and his staff officer Landillon in 1895, and fossils and geologic data were sent to paleontologist Charles Depéret.[3] He briefly described the formation and named two dinosaurs from the remains (Titanosaurus madagascariensis and Megalosaurus crenatissimus, now Majungasaurus).[4] Similar collections were made throughout the 20th century, yielding mostly fragmentary fossils;[3] one such specimen, a rough partial skull roof, became the holotype of supposed pachycephalosaur (bonehead dinosaur) Majungatholus in 1979.[5] (This specimen was later shown to be part of the skull ornamentation of a Majungasaurus.) Large scale expeditions (seven to date), under the banner of the Mahajanga Basin Project, began in 1993. These expeditions, conducted jointly by Stony Brook University and the University of Antananarivo, have greatly expanded knowledge of this formation and the organisms that lived while it was being deposited.[3]

Paleoenvironment

The Maevarano Formation is interpreted as a low-relief alluvial plain that over time was covered by a marine transgression. Broad, shallow rivers flowed to the northwest from central highlands; evidence for debris flows suggests that the discharges of the rivers varied greatly, with periods of dilute water flow, and periods of rapid erosion dumping sediment into the channels. Paleosols are reddish and include root casts. The paleosols and other sedimentologic evidence indicate well-drained floodplains with abundant vegetation adapted to a relatively dry climate, strongly seasonal (rainy and dry seasons) and at times semiarid (not unlike the present climate of the area).[1]

Vertebrate paleofauna

Animals found in the formation include frogs (including Beelzebufo ampinga),[6] turtles, snakes, lizards, at least seven species of crocodyliforms (including species of Mahajangasuchus and Trematochampsa), abelisaurid theropods Majungasaurus, noasaurid Masiakosaurus, two types of titanosaurian sauropods (Rapetosaurus and an unnamed second form), and at least five species of birds or very bird-like dinosaurs, including Rahonavis. The 6 to 7 meter long (20 to 23 ft) Majungasaurus was likely the apex predator in the terrestrial environment. Crocodyliforms were very diverse and abundant.[1]

Amphibians

| Amphibians of the Maevarano Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

Beelzebufo ampinga |

A large frog. |

| ||||

Dinosaurs

Indeterminate Lithostrotia remains formerly attributed to the titanosauridae. Undescribed Lithostrotia form. Indeterminate Enantiornithes remains. Possible indeterminate spinosaurid remains.

Color key

|

Notes Uncertain or tentative taxa are in small text; |

| Dinosaurs reported from the Maevarano Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

M. crenatissimus[7] |

"Partial mandible."[8] |

An abelisaur. |

| |||

|

M. knopfleri[7] |

"Disarticulated remains of at least 6 individuals," as well as other isolated fossils.[9] |

A noasaurid abelisaur. | ||||

|

R. ostromi[7] |

"Partial postcranial skeleton."[10] |

A dromaeosaurid. | ||||

|

Rapetosaurus krausei[7] |

"[Three] skulls, at least [one] postcranial skeleton."[11] |

A titanosaur. | ||||

|

S. madagascariensis[7] |

"Teeth."[12] |

Possible indeterminate ornithischian remains.[7] | ||||

|

T. madagascariensis[7] |

||||||

Birds

| Birds of the Maevarano Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

V. berivotrensis[7] |

"Partial hindlimbs."[13] |

An ornithuromorph. | ||||

Crocodylomorphs

| Crocodylomorphs of the Maevarano Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

M. insignis |

A peirosaurid. |

| ||||

|

M. oblita |

Formerly known as Trematochampsa oblita. | |||||

|

S. clarki |

A chimaerasuchid. | |||||

|

T. oblita |

A trematochampsid. Later referred to Miadanasuchus oblita [14] | |||||

|

A. tsangatsangana |

A notosuchian. | |||||

Snakes

| Snakes of the Maevarano Formation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genus | Species | Location | Stratigraphic position | Material | Notes | Images |

|

K. hechti |

A nigerophiid snake. |

|||||

|

M. nosymena |

Vertebrae and rib fragments. |

|||||

Mammals

Mammals known from the Maevarano Formation include the gondwanathere Lavanify miolaka, known from two teeth, two more teeth that may represent a second gondwanathere, the broken tooth UA 8699, which as been interpreted both as metatherian and as eutherian, a multituberculate tooth fragment, and a yet undescribed mammal known from an articulated skeleton.[15]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Rogers, Raymond R.; Krause, David W.; Curry Rogers, Kristina; Rasoamiaramanana, Armand H.; & Rahantarisoa, Lydia. (2007). "Paleoenvironment and Paleoecology of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". In Sampson, Scott D.; & Krause, David W. (eds.). Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 8. pp. 21–31.

- ↑ Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loueff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth M.P.; and Noto, Christopher N. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 604. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Krause, David W.; Sampson, Scott D.; Carrano, Matthew T.; & O'Connor, Patrick M. (2007). "Overview of the history of discovery, taxonomy, phylogeny, and biogeography of Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". In Sampson, Scott D.; & Krause, David W. (eds.). Majungasaurus crenatissimus (Theropoda: Abelisauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 8. pp. 1–20.

- ↑ Depéret, Charles. (1896). "Note sur les Dinosauriens Sauropodes et Théropodes du Crétacé supérieur de Madagascar". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France (in French) 21: 176–194.

- ↑ Sues, Hans-Dieter; & Taquet, Phillipe. (1979). "A pachycephalosaurid dinosaur from Madagascar and a Laurasia−Gondwanaland connection in the Cretaceous". Nature 279 (5714): 633–635. doi:10.1038/279633a0.

- ↑ Evans, Susan E.; Jones, Marc E. H.; Krause, David W. (2008). "A giant frog with South American affinities from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (8): 2951–2956. doi:10.1073/pnas.0707599105. PMC 2268566. PMID 18287076.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 "83.2 Faritany Majunga, Madagascar; 3. Maevarano Formation," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 605.

- ↑ "Table 3.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 50.

- ↑ "Table 3.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 49.

- ↑ "Table 11.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 211.

- ↑ "Table 13.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 270.

- ↑ "Table 14.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 326.

- ↑ "Table 11.1," in Weishampel, et al. (2004). Page 212.

- ↑ Erin L. Rasmusson Simons and Gregory A. Buckley (2009). "New Material of "Trematochampsa" Oblita (Crocodyliformes,Trematochampsidae) from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 29 (2): 599–604. doi:10.1671/039.029.0224.

- ↑ Krause, D.W.; O'Connor, P.M.; Rogers, K.C.; Sampson, S.D.; Buckley, G.A.; Rogers, R.R. (2006). "Late Cretaceous terrestrial vertebrates from Madagascar: Implications for Latin American biogeography". Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 93 (2): 178–208. doi:10.3417/0026-6493(2006)93[178:LCTVFM]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 40035721.

References

- Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.