Mühlviertler Hasenjagd

The Mühlviertler Hasenjagd was a Nazi war crime that took place near Linz in the Mühlviertel, a region in Upper Austria. In February 1945, around 500 Soviet prisoners escaped from Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp in the Mühlviertel. Local civilians, soldiers and local Nazi organizations hunted down the escapees for three weeks, murdering most of them. Of the original 500 prisoners who took part in the escape attempt, eleven managed to succeed, remaining free till the end of the war.

The SS later referred to the three-week search as a hasenjagd, or "rabbit chase". The outbreak itself and the fact that some did manage to escape were unique in Mauthausen's history.

Breakout and escape

In the night hours of February 2, 1945, some 500 "K" prisoners, mostly Soviet officers from barracks 20, known as the "death barracks" (Todesblock) made an attempt to escape Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp.[1] Using fire extinguishers from the barracks and blankets and boards as projectiles, one group attacked and occupied a watch tower while a second group used wet blankets and bits of clothing to cause a short circuit in the electrified fence. The prisoners then climbed over the fence.[2][3]

Of those 500, 419 prisoners did manage to leave the camp grounds[4] but many escapees were already too weakened from starvation to reach the woods and collapsed in the snow outside the camp, where they were shot that night by SS machine guns. All who failed to reach the woods and another 75 prisoners in the barracks who had remained behind because they were too sick to follow, were executed that night. Over 300 prisoners did manage to reach the woods that first night.[4][5]

Pursuit

The SS camp commandant immediately called a major search, asking help from the local population. In addition to pursuit by the SS, the escapees were hunted down by SA divisions, the gendarmerie, the Wehrmacht, the Volkssturm and the Hitler Youth. Local citizens were also incited to take part. The SS camp commandant ordered the gendarmerie "not to bring anyone back alive".[2] No one was forced to participate in the manhunt, they did it willingly.[3]

The majority of the escapees were apprehended and most were shot or beaten to death on the spot. Some 40 murdered prisoners' bodies were taken to Ried in der Riedmark, where the search was based, and stacked in a pile of corpses, "just like the bag at an autumn hunt", as one former gendarme, Otto Gabriel, put it.[2][5] Members of the Volkssturm who brought prisoners back to Mauthausen were berated for not having beaten them to death instead. Of the 300 who did survive the escape that first night, 57 were returned to the camp.[5]

The Linz criminal investigations department later reported to the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, "Of the 419 fugitives [who managed to leave the camp] [...], in and around Mauthausen, Gallneukirchen, Wartberg, Pregarten, Schwertberg and Perg, over 300 were taken again, including 57 alive."[1][4]

Just 11 officers are known to have survived the manhunt till the end of World War II. In spite of the extremely high risk, a few farm families and civilian forced laborers hid escapees or brought food to those hiding in the woods.[2] After three months, the war ended and the fugitives were safe.

After 1945: reconciling the past

The events of the Mühlviertel massacre gained prominence with the 1994 film The Quality of Mercy by director Andreas Gruber. Although it received a lukewarm review from Variety,[6] the film was a box office success in Austria.

While he was making the film, Gruber invited Bernard Bamberger to make a behind-the-scenes documentary about the film and compare the movie with the actual events. Aktion K contrasts interviews with local residents about the film and the actual history with archival footage and the eye witness testimony of Mikhail Ribchinsky, a survivor of the Mühlviertler Hasenjagd.[7][8] Bamberger was awarded the "Austrian People's Education TV" award for "Best Documentary" in 1995.[9] Aktion K has since been broadcast several times on German-language television.

Legacy

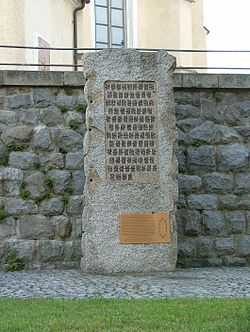

A memorial to the Mühlviertler Hasenjagd was unveiled in Ried an der Riedmark on May 5, 2001, 56 years after the liberation of Mauthausen-Gusen concentration camp. The monument was erected at the initiative of the Ried Socialist Youth.[10] The three-meter (9.8 feet) tall granite boulder was donated by the Mauthausen Committee. The monument's face is engraved with 489 hash marks representing those murdered during the course of the escape attempt; the exact number of victims is unknown.[11]

In conjunction with the commemoration of the anniversary of the camp's liberation, the Socialist Youth of Austria and Socialist Youth of Germany held a program at the new monument for the Mühlviertler Hasenjagd. Attending were three surviving former Soviet prisoners from Mauthausen, Prof. Tigran Drambyan, Roman Bulkatch and Nikolai Markevitch.[11]

See also

- Sobibor extermination camp (uprising and escape on October 14, 1943)

- Nazi war crimes

- Celler Hasenjagd (massacre of concentration camp prisoners, Celle, Oct. 8, April 1945)

- Rechnitz massacre

- Postenpflicht

- February Shadows

Sources

- Linda DeMeritt, "Representations of History: The Mühlviertler Hasenjagd as Word and Image" in Modern Austrian Literature, Nr. 32.4, (1999) pp. 134–145

- Thomas Karny, Die Hatz : Bilder zur Mühlviertler „Hasenjagd“, Verlag Franz Steinmaßl, Grünbach, Austria (1992) Geschichte der Heimat Edition. ISBN 3-900943-12-5 (German)

- Walter Kohl, Auch auf dich wartet eine Mutter. Die Familie Langthaler inmitten der „Mühlviertler Hasenjagd”, Verlag Franz Steinmaßl, Grünbach, Austria (2005) Geschichte der Heimat Edition. ISBN 3-902427-24-8 (German)

- Alphons Matt, Einer aus dem Dunkel: die Befreiung des Konzentrationslagers Mauthausen durch den Bankbeamten H. SV Internat., Schweizer Verl.-Haus, Zürich (1988) ISBN 3-7263-6574-5 (German)

- Elisabeth Reichart, Februarschatten, Müller Verlag, Salzburg and Vienna (1995) ISBN 3-7013-0899-3 (German)

- Elisabeth Reichart, Februarschatten, Aufbau-Taschenbuch-Verl., Berlin (1997) ISBN 3-7466-1284-5 (German)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ernst Gusenbauer, "Was man erwischt, wird kalt erschossen: Ried in der Riedmark und die Mühlviertler Hasenjagd 2. Februar 1945" (PDF) Oberösterreichicher Heimatblätter Vol. 46, Heft 2 (1992) pp. 263-267. Retrieved May 8, 2010 (German)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Mauthausen Memorial, official website See Concentration camp > History 1938-1945 > Disease, Violence, Death > "Mühlviertel rabbit chase". Article on the Mühlviertel Hasenjagd with photos and eye-witness testimony. Retrieved May 7, 2010

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Mauthausen Concentration Camp - Commemoration and Reflection" City of Vienna, official website. Retrieved May 7, 2010

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Alphons Matt, Einer aus dem Dunkel, (1988) p. 75 (German)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Memorial 'Mühlviertler Hasenjagd'" Retrieved May 7, 2010

- ↑ Joe Lydon, "The Quality of Mercy" Variety review. (October 17, 1994) Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ Cathy Meils, "Aktion K" Variety review. (November 7, 1994) Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ "Aktion K (1994)" Documentary synopsis. Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ "Austrian People's Education TV Award" The Internet Movie Database (June 28, 1995) Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ "Exposure of a memorial statue for the "Mühlviertler Hasenjagd" in Ried" Österreichischer Rundfunk online archive for May 5, 2001. Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Sabine Schatz, "Mahnmal für die Opfer der „Mühlviertler Hasenjagd“ errichtet!" Article about the unveiling of the monument in Ried an der Riedmark on May 5, 2001

External links

- Ausschnitte aus der Dokumentation der Gedenkstätte KZ Mauthausen (PDF) Eye-witness reports and citations from original documents. (330 kB) (German)

- Hasenjagd Movie website (German)