Luther's canon

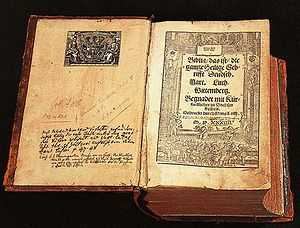

Luther's canon is the name of the biblical canon attributed to Martin Luther, which has influenced Protestants since the 16th century Protestant Reformation. While the Lutheran Confessions specifically did not define a canon, it is widely regarded as the canon of the Lutheran Church. It differs from the 1546 Roman Catholic canon of the Council of Trent in that it rejects the Deuterocanon and questions the seven New Testament books, called "Luther's Antilegomena",[1] four of which are still ordered last in German-language Luther Bibles to this day.[2][3]

Deuterocanonical books

Luther eliminated the deuterocanonical books from the Catholic Old Testament, terming them "Apocrypha, that are books which are not considered equal to the Holy Scriptures, but are useful and good to read".[4] He also argued unsuccessfully for the relocation of the Book of Esther from the canon to the Apocrypha, because without the deuterocanonical additions to the Book of Esther, the text of Esther never mentions God. As a result, Protestants and Catholics continue to use different canons, which differ both in respect to the Old Testament and in the concept of the Antilegomena of the New Testament.

Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation

Luther made an attempt to remove the books of Hebrews, James, Jude and Revelation from the canon (notably, he perceived them to go against certain Protestant doctrines such as sola gratia and sola fide), but this was not generally accepted among his followers. However, these books are ordered last in the German-language Luther Bible to this day.[5]

"If Luther's negative view of these books were based only upon the fact that their canonicity was disputed in early times, 2 Peter might have been included among them, because this epistle was doubted more than any other in ancient times". [6] However, the prefaces that Luther affixed to these four books makes it evident "that his low view of them was more due to his theological reservations than with any historical investigation of the canon".[7]

Luther's views on James

In his book Basic Theology, Charles Caldwell Ryrie countered the claim that Luther rejected the Book of James as being canonical.[8] In his preface to the New Testament, Luther ascribed to several books of the New Testament different degrees of doctrinal value: "St. John's Gospel and his first Epistle, St. Paul's Epistles, especially those to the Romans, Galatians, Ephesians, and St. Peter's Epistle-these are the books which show to thee Christ, and teach everything that is necessary and blessed for thee to know, even if you were never to see or hear any other book of doctrine. Therefore, St. James' Epistle is a perfect straw-epistle compared with them, for it has in it nothing of an evangelic kind." Thus Luther was comparing (in his opinion) doctrinal value, not canonical validity.

However, Ryrie's theory is countered by other Biblical scholars, including William Barclay, who note that Luther stated plainly, if not bluntly: "I think highly of the epistle of James, and regard it as valuable although it was rejected in early days. It does not expound human doctrines, but lays much emphasis on God’s law. …I do not hold it to be of apostolic authorship."[9]

Sola fide doctrine

In The Protestant Spirit of Luther’s Version, Philip Schaff asserts that:

| “ | The most important example of dogmatic influence in Luther’s version is the famous interpolation of the word alone in Rom. 3:28 (allein durch den Glauben), by which he intended to emphasize his solifidian doctrine of justification, on the plea that the German idiom required the insertion for the sake of clearness. But he thereby brought Paul into direct verbal conflict with James, who says (James 2:24), "by works a man is justified, and not only by faith" ("nicht durch den Glauben allein"). It is well known that Luther deemed it impossible to harmonize the two apostles in this article, and characterized the Epistle of James as an "epistle of straw," because it had no evangelical character ("keine evangelische Art").[10] | ” |

Similar canons of the time

In his book Canon of the New Testament, Bruce Metzger notes that in 1596 Jacob Lucius published a Bible at Hamburg which labeled Luther's four as "Apocrypha"; David Wolder the pastor of Hamburg's Church of St. Peter published in the same year a triglot Bible which labeled them as "non canonical"; J. Vogt published a Bible at Goslar in 1614 similar to Lucius'; Gustavus Adolphus of Stockholm in 1618 published a Bible with them labeled as "Apocr(yphal) New Testament."[11]

Protestant laity and clergy

There is some evidence that the first decision to omit these books entirely from the Bible was made by Protestant laity rather than clergy. Bibles dating from shortly after the Reformation have been found whose tables of contents included the entire Roman Catholic canon, but which did not actually contain the disputed books, leading some historians to think that the workers at the printing presses took it upon themselves to omit them. However, Anglican and Lutheran Bibles usually still contained these books until the 20th century, while Calvinist Bibles did not. Several reasons are proposed for the omission of these books from the canon. One is the support for Catholic doctrines such as Purgatory and Prayer for the dead found in 2 Maccabees. Another is that the Westminster Confession of Faith of 1646, during the English Civil War, actually excluded them from the canon. Luther himself said he was following Jerome's teaching about the Veritas Hebraica.

Modern Evangelical use of the canon

Evangelicals tend not to accept the Septuagint as the inspired Hebrew Bible, though many of them recognize its wide use by Greek-speaking Jews in the first century. They note that Melito of Sardis listed all the books of the Old Testament except the book of Esther (see Melito's canon).

Many modern Protestants point to four "Criteria for Canonicity" to justify the books that have been included in the Old and New Testament, which are judged to have satisfied the following:

- Apostolic Origin – attributed to and based on the preaching/teaching of the first-generation apostles (or their close companions).

- Universal Acceptance – acknowledged by all major Christian communities in the ancient world (by the end of the fourth century).

- Liturgical Use – read publicly when early Christian communities gathered for the Lord's Supper (their weekly worship services).

- Consistent Message – containing a theological outlook similar or complementary to other accepted Christian writings.

It is often difficult to apply these criteria to all books in the accepted canon, however.

References

- ↑ Luther's Antilegomena at bible-researcher.com

- ↑ "Gedruckte Ausgaben der Lutherbibel von 1545". note order: …Hebräer, Jakobus, Judas, Offenbarung

- ↑ "German Bible Versions".

- ↑ The Popular and Critical Bible Encyclopædia and Scriptural Dictionary, Fully Defining and Explaining All Religious Terms, Including Biographical, Geographical, Historical, Archæological and Doctrinal Themes, p.521, edited by Samuel Fallows et al, The Howard-Severance company, 1901,1910. - Google Books

- ↑ http://www.bibelcenter.de/bibel/lu1545/ note order: ... Hebr�er, Jakobus, Judas, Offenbarung; see also http://www.bible-researcher.com/links10.html

- ↑ Luther's Antilegomena at bible-researcher.com

- ↑ Luther's Antilegomena at bible-researcher.com

- ↑ Ryrie, Charles Caldwell. Basic Theology.

- ↑ Martin Luther, as quoted by William Barclay, The Daily Study Bible Series, The Letters of James and Peter, Revised Edition, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, KY, 1976, p. 7

- ↑ "History of the Christian Church, book 7, chapter 4".

- ↑ Metzger, Bruce. Canon of the New Testament.