Luneburg lens

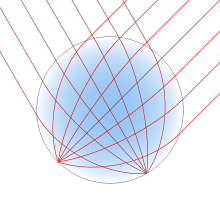

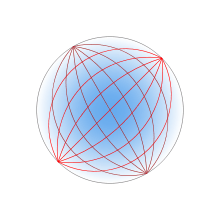

A Luneburg lens (originally Lüneburg lens, often incorrectly spelled Luneberg lens) is a spherically symmetric lens that has varying index of refraction inside it. A typical Luneburg lens's refractive index n decreases radially from the center to the outer surface.

For certain index profiles, the lens will form perfect geometrical images of two given concentric spheres onto each other. There are an infinite number of refractive-index profiles that can produce this effect. The simplest such solution was proposed by Rudolf Luneburg in 1944.[1] Luneburg's solution for the refractive index creates two conjugate foci outside of the lens. The solution takes a simple and explicit form if one focal point lies at infinity, and the other on the opposite surface of the lens. J. Brown and A. S. Gutman subsequently proposed solutions which generate one internal focal point and one external focal point.[2][3] These solutions are not unique; the set of solutions are defined by a set of definite integrals which must be evaluated numerically.[4]

Luneburg lenses are one type of gradient-index lens. They can be made for use with electromagnetic radiation from visible light to radio waves.

Designs

Luneburg's solution

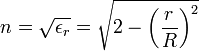

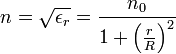

Each point on the surface of an ideal Luneburg lens is the focal point for parallel radiation incident on the opposite side. Ideally, the dielectric constant  of the material composing the lens falls from 2 at its center to 1 at its surface (or equivalently, the refractive index

of the material composing the lens falls from 2 at its center to 1 at its surface (or equivalently, the refractive index  falls from

falls from  to 1), according to

to 1), according to

where  is the radius of the lens. Because the refractive index at the surface is the same as that of the surrounding medium, no reflection occurs at the surface. Within the lens, the paths of the rays are arcs of ellipses.

is the radius of the lens. Because the refractive index at the surface is the same as that of the surrounding medium, no reflection occurs at the surface. Within the lens, the paths of the rays are arcs of ellipses.

Maxwell's fish-eye lens

Maxwell's fish-eye lens is also an example of the generalized Luneburg lens. The fish-eye, which was first fully described by Maxwell in 1854[5] (and therefore pre-dates Luneburg's solution), has a refractive index varying according to

.

.

It focuses each point on the spherical surface of radius R to the opposite point on the same surface. Within the lens, the paths of the rays are arcs of circles.

Publication and attribution

The properties of this lens are described in one of a number of set problems or puzzles in the 1853 Cambridge and Dublin Mathematical Journal.[6] The challenge is to find the refractive index as a function of radius, given that a ray describes a circular path, and further to prove the focusing properties of the lens. The solution is given in the 1854 edition of the same journal.[5] The problems and solutions were originally published anonymously, but the solution of this problem (and one other) were included in Niven's The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell,[7] which was published eleven years after Maxwell's death.

Applications

In practice, Luneburg lenses are normally layered structures of discrete concentric shells, each of a different refractive index. These shells form a stepped refractive index profile that differs slightly from Luneburg's solution. This kind of lens is usually employed for microwave frequencies, especially to construct efficient microwave antennas and radar calibration standards. Cylindrical analogues of the Luneburg lens are also used for collimating light from laser diodes.

Radar reflector

A radar reflector can be made from a Luneburg lens by metallizing parts of its surface. Radiation from a distant radar transmitter is focussed onto the underside of the metallization on the opposite side of the lens; here it is reflected, and focussed back onto the radar station. A difficulty with this scheme is that metallized regions block the entry or exit of radiation on that part of the lens, but the non-metallized regions result in a blind-spot on the opposite side.

Microwave antenna

A Luneburg lens can be used as the basis of a high-gain radio antenna. This antenna is comparable to a dish antenna, but uses the lens rather than a parabolic reflector as the main focusing element. As with the dish antenna, a feed to the receiver or from the transmitter is placed at the focus, the feed typically consisting of a horn antenna. The phase centre of the feed horn must coincide with the point of focus, but since the phase centre is invariably somewhat inside the mouth of the horn, it cannot be brought right up against the surface of the lens. Consequently it is necessary to use a variety of Luneburg lens that focusses somewhat beyond its surface,[8] rather than the classic lens with the focus lying on the surface.

A Luneburg lens antenna offers a number of advantages over a parabolic dish. Because the lens is spherically symmetric, the antenna can be steered by moving the feed around the lens, without having to bodily rotate the whole antenna. Again, because the lens is spherically symmetric, a single lens can be used with several feeds looking in widely different directions. In contrast, if multiple feeds are used with a parabolic reflector, all must be within a small angle of the optical axis to avoid suffering coma (a form of de-focussing). Apart from offset systems, dish antennas suffer from the feed and its supporting structure partially obscuring the main element (aperture blockage); in common with other refracting systems, the Luneburg lens antenna avoids this problem.

A variation on the Luneburg lens antenna is the hemispherical Luneburg lens antenna or Luneburg reflector antenna. This uses just one hemisphere of a Luneburg lens, with the cut surface of the sphere resting on a reflecting metal ground plane. The arrangement halves the weight of the lens, and the ground plane provides a convenient means of support. However, the feed does partially obscure the lens when the angle of incidence on the reflector is less than about 45°.

Path of a ray within the lens

For any spherically symmetric lens, each ray lies entirely in a plane passing through the centre of the lens. The initial direction of the ray defines a line which together with the centre-point of the lens identifies a plane bisecting the lens. Being a plane of symmetry of the lens, the gradient of the refractive index has no component perpendicular to this plane to cause the ray to deviate either to one side of it or the other. In the plane, the circular symmetry of the system makes it convenient to use polar coordinates  to describe the ray's trajectory.

to describe the ray's trajectory.

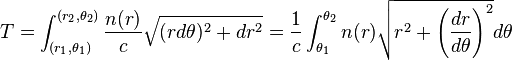

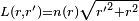

Given any two points on a ray (such as the point of entry and exit from the lens), Fermat's principle asserts that the path that the ray takes between them is that which it can traverse in the least possible time. Given that the speed of light at any point in the lens is inversely proportional to the refractive index, and by Pythagoras, the time of transit between two points  and

and  is

is

where  is the speed of light in vacuum. Minimizing this

is the speed of light in vacuum. Minimizing this  yields a second-order differential equation determining the dependence of

yields a second-order differential equation determining the dependence of  on

on  along the path of the ray. This type of minimization problem has been extensively studied in Lagrangian mechanics, and a ready-made solution exists in the form of the Beltrami identity, which immediately supplies the first integral of this second order equation. Substituting

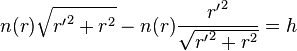

along the path of the ray. This type of minimization problem has been extensively studied in Lagrangian mechanics, and a ready-made solution exists in the form of the Beltrami identity, which immediately supplies the first integral of this second order equation. Substituting  (where

(where  represents

represents  ), into this identity gives

), into this identity gives

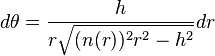

where  is a constant of integration. This first-order differential equation is separable, that is it can be re-arranged so that

is a constant of integration. This first-order differential equation is separable, that is it can be re-arranged so that  only appears on one side and

only appears on one side and  only on the other:

only on the other:

.[1]

.[1]

The parameter  is a constant for any given ray, but differs between rays passing at different distances from the centre of the lens. For rays passing through the centre, it is zero. In some special cases, such as for Maxwell's fish-eye, this first order equation can be further integrated to give a formula for

is a constant for any given ray, but differs between rays passing at different distances from the centre of the lens. For rays passing through the centre, it is zero. In some special cases, such as for Maxwell's fish-eye, this first order equation can be further integrated to give a formula for  as a function or

as a function or  . In general it provides the relative rates of change of

. In general it provides the relative rates of change of  and

and  , which may be integrated numerically to follow the path of the ray through the lens.

, which may be integrated numerically to follow the path of the ray through the lens.

See also

- Gravitational lenses also have a radially decreasing refractive index.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Luneburg, R. K. (1944). Mathematical Theory of Optics. Providence, Rhode Island: Brown University. pp. 189–213.

- ↑ Brown, J. (1953). Wireless Engineer 30: 250.

- ↑ Gutman, A. S. (1954). "Modified Luneberg Lens". J. Appl. Phys. 25 (7): 855. Bibcode:1954JAP....25..855G. doi:10.1063/1.1721757.

- ↑ Morgan, S. P. (1958). "General solution of the Luneburg lens problem". J. Appl. Phys. 29 (9): 1358–1368. Bibcode:1958JAP....29.1358M. doi:10.1063/1.1723441.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Solutions of problems (prob. 3, vol. VIII. p. 188)". The Cambridge and Dublin mathematical journal (Macmillan) 9: 9–11. 1854.

- ↑ "Problems (3)". The Cambridge and Dublin mathematical journal (Macmillan) 8: 188. 1853.

- ↑ Niven, ed. (1890). The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell. New York: Dover Publications. p. 76.

- ↑ Lo, Y. T.; Lee, S. W. (1993). Antenna Handbook: Antenna theory. Antenna Handbook. Springer. p. 40. ISBN 9780442015930.

External links

- Animation of propagation through a Luneburg Lens (Dielectric Antenna) from YouTube

- Animation of a Maxwell's Fish-Eye Lens from YouTube

- Animation of a Half Maxwell's Fish-Eye Lens (Dielectric Antenna) from YouTube