Lowell Mill Girls

The "Lowell Mill Girls" (or "Factory Girls," as they called themselves) were female workers who came to work for the textile corporations in Lowell, Massachusetts, during the Industrial Revolution in the United States. The women initially recruited by the corporations were daughters of propertied New England farmers, between the ages of 15 and 30. (There also could be little girls who worked there about the age of 13.) By 1840, at the height of the Industrial Revolution, the textile mills had recruited over 8,000 women, who came to make up nearly seventy-five percent of the mill workforce.

During the early period, women came to the mills of their own accord, for various reasons: to help a brother pay for college, for the educational opportunities offered in Lowell, or to earn a supplementary income for themselves. While their wages were only half of what men were paid, many were able to attain economic independence for the first time, free from the controlling influence of fathers and husbands. As a result, while factory life would soon come to be experienced as oppressive, it enabled these women to challenge the myths of female inferiority and dependence.

As the nature of the new "factory system" became clear, however, many women joined the broader American labor movement, to protest the dramatic social changes being brought by the Industrial Revolution. While they decried the deteriorating factory conditions, worker unrest in the 1840s was directed mainly against the loss of control over economic life. This loss of control, which came with the dependence on the corporations for a wage, was experienced as an attack on their dignity and independence. In 1845, after a number of protests and strikes, many operatives came together to form the first union of working women in the United States, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. The Association adopted a newspaper called the Voice of Industry, in which workers published sharp critiques of the new industrialism. The Voice stood in sharp contrast to other literary magazines published by female operatives, such as the Lowell Offering, which painted a sanguine picture of life in the mills.

Industrialization of Lowell

| Part of a series on |

| Organized labour |

|---|

|

|

Academic disciplines |

In 1813, businessman Francis Cabot Lowell formed a company, the Boston Manufacturing Company and built a textile mill next to the Charles River in Waltham, Massachusetts. Differing from the earlier Rhode Island System, where only carding and spinning were done in a factory while the weaving was often put out to neighboring farms to be done by hand, the Waltham mill was the first integrated mill in the United States, transforming raw cotton into cotton cloth in one building. While Lowell died in 1817, his operation was quite successful and his business partners looked to replicate their success on a larger scale.[1]

In 1823, the investors organized the Merrimack Manufacturing Company and purchased land near Pawtucket Falls to expand its textile manufacturing operations. In 1826, the land was incorporated as a separate town, and being primarily concerned with and run by the textile interests, was named "Lowell" in honor of the late Francis Cabot Lowell. In less than 20 years, a sparse collection of family farms was transformed into the industrial city of Lowell, Massachusetts. In that time, ten textile corporations opened 32 mills in the city.[2] Women were "collected" or recruited by men telling tales of high wages available to "all classes of people." In 1840, the factories employed almost 8,000 workers — mostly women between the ages of 16 and 35.[2][3]

The "City of Spindles", as Lowell came to be known, quickly became the center of the Industrial Revolution in America. New, large scale machinery, which had come to dominate the production of cloth by 1840, was being rapidly developed in lockstep with the equally new ways of organizing workers for mass production. Together, these mutually reinforcing technological and social changes produced staggering increases: between 1840 to 1860, the number of spindles in use went from 2¼ million to almost 5¼ million; bales of cotton used from 300,000 to nearly 1 million, and the number of workers from 72,000 to nearly 122,000. This tremendous growth translated directly into large profits for the textile corporations: between 1846 and 1850, for instance, the dividends of the Boston based investors, the group of textile companies that founded Lowell, averaged 14 percent per year. Most corporations recorded similarly high profits during this period.

Work and living environment

The social position of the factory girls had been degraded considerably in France and England. In her autobiography, Harriet Robinson (who worked in the Lowell mills from 1834–1848) suggests that "It was to overcome this prejudice that such high wages had been offered to women that they might be induced to become mill girls, in spite of the opprobrium that still clung to this degrading occupation.…"[3]

Factory conditions

The Lowell System combined large-scale mechanization with an attempt to improve the stature of its female workforce and workers. A few girls who came with their mothers or older sisters were as young as ten years old, some were middle-aged, but the average age was about 24.[3] Usually hired for contracts of one year (the average stay was about four years), new employees were given assorted tasks as spare hands and paid a fixed daily wage while more experienced loom operators would be paid by the piece. They were paired with more experienced women, who trained them in the ways of the factory.[2]

Conditions in the Lowell mills were severe by modern American standards. Employees worked from 5:00 am until 7:00 pm, for an average 73 hours per week.[2][3] Each room usually had 80 women working at machines, with two male overseers managing the operation. The noise of the machines was described by one worker as "something frightful and infernal," and although the rooms were hot, windows were often kept closed during the summer so that conditions for thread work remained optimal. The air, meanwhile, was filled with particles of thread and cloth.[4]

The English novelist Charles Dickens, who visited in 1842, remarked favorably on the conditions:[5] "I cannot recall or separate one young face that gave me a painful impression; not one young girl whom, assuming it to be matter of necessity that she should gain her daily bread by the labour of her hands, I would have removed from those works if I had had the power"" However, there was concern among many workers that foreign visitors were being presented with a sanitized view of the mills, by textile corporations who were trading on the image of the ‘literary operative’ to mask the grim realities of factory life. “Very pretty picture,” wrote an operative in the Voice of Industry, responding to a rosy account of life and learning in the mills, “but we who work in the factory know the sober reality to be quite another thing altogether.” The “sober reality” was twelve to fourteen hours of dreary, exhausting work, which many workers experienced as hostile to intellectual development.

Living quarters

The investors or factory owners built hundreds of boarding houses near the mills, where textile workers lived year-round. A curfew of 10:00 pm was common, and men were generally not allowed inside. About 25 women lived in each boarding house, with up to six sharing a bedroom.[2] One worker described her quarters as "a small, comfortless, half-ventilated apartment containing some half a dozen occupants".[6] Trips away from the boarding house were uncommon; the Lowell girls worked and ate together. However, half-days and short paid vacations were possible due to the nature of the piece-work; one girl would work the machines of another in addition to her own such that no wages would be lost but they would be lost if they stopped working.

These close quarters fostered community as well as resentment. Newcomers were mentored by older women in areas such as dress, speech, behavior, and the general ways of the community. Workers often recruited their friends or relatives to the factories, creating a familial atmosphere among many of the rank and file.[2] The Lowell girls were expected to attend church and demonstrate morals befitting proper society. The 1848 Handbook to Lowell proclaimed that "The company will not employ anyone who is habitually absent from public worship on the Sabbath, or known to be guilty of immorality."[7]

Working Class Intellectual Culture

For many young women, the allure of Lowell was in the opportunities afforded for further study and learning. Most had already completed some measure of formal education and were resolutely bent on of self-improvement. Upon their arrival, they found a vibrant, lively working class intellectual culture: workers read voraciously in Lowell’s city library and Reading Rooms, and subscribed to the large, informal “circulating libraries” which trafficked in novels. Many even pursued literary composition. Defying factory rules, operatives would affix verses to their spinning frames, “to train their memories,” and pin up mathematical problems in the rooms where they worked. In the evenings, many enrolled in courses offered by the mills and attended public lectures at the Lyceum, a theatre built at company expense (offering 25 lectures per season for 25 cents). The Voice of Industry is alive with notices for upcoming lectures, courses, and meetings on topics ranging from astronomy to music. ("Lectures and Learning", Voice of Industry)

The corporations happily publicized the efforts of these “literary mill girls”, boasting that they were the “most superior class of factory operative,” which greatly impressed foreign visitors to Lowell. But this masked the bitter opposition of many workers to the twelve to fourteen hours of monotonous, exhausting work, which they saw was corrosive to their desire to learn and educate themselves. “Who,” asked an operative writing in the Voice, “after thirteen hours of steady application to monotonous work, can sit down and apply her mind to deep and long continued thought? …Where is the opportunity for mental improvement?” A former Lowell operative, looking back on her experience in the mills, expressed a similar view: “After one has worked from ten to fourteen hours at manual labor, it is impossible to study History, Philosophy, or Science,” she wrote, “I well remember the chagrin I often felt when attending lectures, to find myself unable to keep awake…I am sure few possessed a more ardent desire for knowledge than I did, but such was the effect of the long hour system, that my chief delight was, after the evening meal, to place my aching feet in an easy position, and read a novel.”

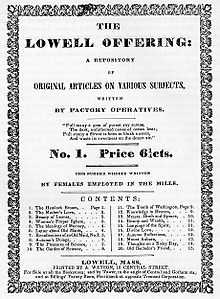

The Lowell Offering

In October 1840, the Reverend Abel Charles Thomas of the First Universalist Church organized a monthly publication by and for the Lowell girls. As the magazine grew in popularity, women contributed poems, ballads, essays and fiction – often using their characters to report on conditions and situations in their lives.[2]

The Offering's contents were by turns serious and farcical. In a letter in the first issue, "A Letter about Old Maids", the author suggested that "sisters, spinsters, lay-nuns, & c" were an essential component of God's "wise design".[8] Later issues – particularly in the wake of labor unrest in the factories – included an article about the value of organizing and an essay about suicide among the Lowell girls.[9]

Strikes of 1834 and 1836

The initial effort of the investors and managers to recruit female textile workers brought generous wages for the time (three to five dollars per week), but with the economic depression of the early 1830s, the Board of Directors proposed a reduction in wages. This, in turn, led to organized "turn-outs" or strikes.

In February 1834, the Board of Directors of Lowell's textile mills requested the managers or agents to impose a 15% reduction in wages, to go into effect on March 1. After a series of meetings, the female textile workers organized a "turn-out" or strike. The women involved in "turn-out" immediately withdrew their savings causing "a run" on two local banks.[10]

The strike failed and within days the women had all returned to work at reduced pay or left town, but the "turn-out" or strike was an indication of the determination among the Lowell female textile workers to take labor action. This dismayed the agents of the factories, who portrayed the turnout as a betrayal of femininity. William Austin, agent of the Lawrence Manufacturing Company, wrote to his Board of Directors, "notwithstanding the friendly and disinterested advice which has been on all proper occassions [sic] communicated to the girls of the Lawrence mills a spirit of evil omen … has prevailed, and overcome the judgment and discretion of too many".[2]

Again, in response to a severe economic depression and the high costs of living, in January 1836, the Board of Directors of Lowell's textile mills absorbed an increase in the textile workers' rent to help in the crisis faced by the company boarding house keepers. As the economic calamity continued in October 1836, the Directors proposed an additional rent hike to be paid by the textile workers living in the company boarding houses.[11] The female textile workers responded immediately in protest by forming the Factory Girls' Association and organizing a "turn-out" or strike. Harriet Hanson Robinson, an eleven-year-old doffer at the time of the strike, recalled in her memoirs: "One of the girls stood on a pump and gave vent to the feelings of her companions in a neat speech, declaring that it was their duty to resist all attempts at cutting down the wages. This was the first time a woman had spoken in public in Lowell, and the event caused surprise and consternation among her audience."[3]

This "turn-out" or strike attracted over 1,500 workers – nearly twice the number two years previously - causing Lowell's textile mills to run far below capacity.[2] Unlike the "turn-out" or strike in 1834, in 1836 there was enormous community support for the striking female textile workers. The proposed rent hike was seen as a violation of the written contract between the employers and the employees. The "turn-out" persisted for weeks and eventually the Board of Directors of Lowell's textile mills rescinded the rent hike. Although the "turn-out" was a success, the weakness of the system was evident, and worsened further in the Panic of 1837.

Lowell Female Labor Reform Association

The sense of community that arose from working and living together contributed directly to the energy and growth of the first union of women workers, the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. Started by twelve operatives in January 1845, its membership grew to 500 within six months, and continued to expand rapidly. The Association was run completely by the women themselves: they elected their own officers and held their own meetings; they helped organize the city’s female workers, and set up branches in other mill towns. They organized fairs, parties, and social gatherings. Unlike many middle-class women activists, the operatives found considerable support from working-class men who welcomed them into their reform organizations and advocated for their treatment as equals.

One of its first actions was to send petitions signed by thousands of textile workers to the Massachusetts General Court demanding a ten-hour work day. In response, the Massachusetts Legislature established a committee chaired by William Schouler, Representative from Lowell, to investigate and hold public hearings, during which workers testified about conditions in the factories and the physical demands of their twelve-hour days. These were the first investigations into labor conditions by a governmental body in the United States.[12] The 1845 Legislative Committee determined that it was not state legislature's responsibility to control the hours of work. The LFLRA called its chairman, William Schouler, a "tool"[citation needed] and worked to defeat him in his next campaign for the State Legislature.[2] A complex election Schouler lost to another Whig candidate over the issue of railroads. The impact of working men [Democrats] and working women [non-voting] was very limited. The next year Schouler was re-elected to the State Legislature.[13]

The Lowell female textile workers continued to petition the Massachusetts Legislature and legislative committee hearings became an annual event. Although the initial push for a ten-hour workday was unsuccessful, the LFLRA continued to grow, affiliating with the New England Workingmen's Association and publishing articles in that organization's Voice of Industry, a pro-labor newspaper.[2] This direct pressure forced the Board of Directors of Lowell's textile mills to reduce the workday by 30 minutes in 1847. The FLRA's organizing efforts spilled over into other nearby towns.[2] In 1847, New Hampshire became the first state to pass a law for a ten-hour workday, although there was no enforcement and workers were often requested to work longer days. By 1848, the LFLRA dissolved as a labor reform organization. Lowell textile workers continued to petition and pressure for improved working conditions nst, in 1853, the Lowell corporations reduced the workday to eleven hours.

The New England textile industry was rapidly expanding in the 1850s and 1860s. Unable to recruit enough Yankee women to fill all the new jobs, to supplement the workforce textile managers turned to survivors of the Great Irish Famine who had recently immigrated to the United States in large numbers. During the Civil War, many of Lowell's cotton mills closed, unable to acquire bales of raw cotton from the South. After the war, the textile mills reopened, recruiting French Canadian men and women. Although large numbers of Irish and French Canadian immigrants moved to Lowell to work in the textile mills, Yankee women still dominated the workforce until the mid-1880s.[14]

Political character of labor activity

The Lowell girls' organizing efforts were notable not only for the "unfeminine" participation of women, but also for the political framework used to appeal to the public. Framing their struggle for shorter work days and better pay as a matter of rights and personal dignity, they sought to place themselves in the larger context of the American Revolution. During the 1834 "turn-out" or strike – they warned that "the oppressing hand of avarice would enslave us,"[2] the women included a poem which read:Let oppression shrug her shoulders,In the 1836 strike, this theme returned in a protest song:

And a haughty tyrant frown,

O'er our noble nation flies.[15]

And little upstart Ignorance,

In mockery look down.

Yet I value not the feeble threats

Of Tories in disguise,

While the flag of Independence

Oh! isn't it a pity, such a pretty girl as IThe most striking example of this political overtone can be found in a series of tracts published by the Female Labor Reform Association entitled Factory Tracts. In the first of these, subtitled "Factory Life As It Is", the author proclaims "that our rights cannot be trampled upon with impunity; that we WILL not longer submit to that arbitrary power which has for the last ten years been so abundantly exercised over us."[6]

Should be sent to the factory to pine away and die?

That I cannot be a slave.[15]

Oh! I cannot be a slave, I will not be a slave,

For I'm so fond of liberty,

This conceptualization of labor activity as philosophically linked with the American project in democracy has been instrumental for other labor organizing campaigns, as noted frequently by MIT professor and social critic Noam Chomsky,[16] who has cited this extended quote from the Lowell Mill Girls on the topic of wage slavery:

"When you sell your product, you retain your person. But when you sellyour labour, you sell yourself, losing the rights of free men and becoming vassals of mammoth establishments of a monied aristocracy that threatens annihilation to anyone who questions their right to enslave and oppress.

"Those who work in the mills ought to own them, not have the status of machines ruled by private despots who are entrenching monarchic principles on democratic soil as they drive downwards freedom and rights, civilization, health, morals and intellectuality in the new commercial feudalism."[17]

See also

References

- ↑ Sobel, Robert (1974). The Entrepreneurs: Explorations Within the American Business Tradition. Chapter 1, "Francis Cabot Lowell: The Patrician as Factory Master". New York: Weybright & Talley. ISBN 0-679-40064-8.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 2.11 2.12 Dublin, Thomas (1975). "Women, Work, and Protest in the Early Lowell Mills: 'The Oppressing Hand of Avarice Would Enslave Us'". Labor History. Online at Whole Cloth: Discovering Science and Technology through American History. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Robinson, Harriet (1883). "Early Factory Labor in New England." Internet History Sourcebooks Project. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ "A Description of Factory Life by an Associationist in 1846". Online at the Illinois Labor History Society. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Dickens, Charles (1842). American Notes. New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60185-6.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "An Operative" (1845). "Some of the Beauties of our Factory System – Otherwise, Lowell Slavery". In Factory Tracts. Factory Life As It Is, Number One. Lowell. Online at the Center for History and New Media. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Hamilton Manufacturing Company (1848). "Factory Rules" in The Handbook to Lowell. Online at the Illinois Labor History Society. Retrieved on March 12, 2009.

- ↑ "Betsy" (1840). "A Letter about Old Maids". Lowell Offering. Series 1, No. 1. Online at the On-Line Digital Archive of Documents on Weaving and Related Topics. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Farley, Harriet (1844). "Editorial: Two Suicides". Lowell Offering. Series 4, No. 9. Online at Primary Sources: Workshops in American History. Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ Boston Transcript (1834). Online at "'Liberty Rhetoric' and Nineteenth-Century American Women". Retrieved on August 27, 2007

- ↑ Faragher, John Mack, et al. Out Of Many. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Pearson Hall, 2006. Pg 346

- ↑ Zinn, Howard (1980). A People's History of the United States, p. 225. New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-092643-0.

- ↑ Charles Cowley, Illustrated History of Lowell. Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1868

- ↑ Robert G. Layer, Earnings of Cotton Mill Operatives, 1825-1914. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1955.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Quoted in "'Liberty Rhetoric' and Nineteenth-Century American Women". Retrieved on August 27, 2007.

- ↑ See, for example, Activism, Anarchy, and Power. Interview by Harry Kreisler. 22 March 2002.

- ↑ Chomsky quoting Lowell Mill Girls from p. 29, "Chomsky on Democracy and Education, edited by C.P. Otero

Further reading

- Cook, Sylvia Jenkins. "'Oh Dear! How the Factory Girls Do Rig Up!': Lowell's Self-Fashioning Workingwomen," New England Quarterly (2010) 83#2 pp. 219-249 in JSTOR

- Dublin, Thomas. "Lowell Millhands" in Transforming Women's Work: New England Lives in the Industrial Revolution (1994) pp 77–118.

- Mrozowski, Stephen A. at al. eds. Living on the Roott: Historical Archeology at the Roott Mills Roardinghouses, Lowell, Massachusetts (University of Massachusetts Press, 1996)

- Ranta, Judith A. Women and Children of the Mills: An Annotated Guide to Nineteenth-Century American Textile Factory Literature (Greenwood Press, 1999),

- Zonderman, David A. Aspirations and Anxieties: New England Workers and the Mechanized Factory System, 1815-1850 (Oxford University Press, 1992)

Primary sources

- Eisler, Benita, ed. The Lowell Offering: Writings by New England Mill Women (1840-1945) (1997) excerpt and text search

External links

- Bringing History Home: Lowell Mill Girl Game University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Lowell History

- Documents from Lowell, 1845-1848 Illinois Labor History Society

- Lowell Mill Girl Letters University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Lowell History

- Mill Life in Lowell Website University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Lowell History

- The Lowell Offering University of Massachusetts Lowell, Center for Lowell History

- The Voice of Industry