Low-discrepancy sequence

In mathematics, a low-discrepancy sequence is a sequence with the property that for all values of N, its subsequence x1, ..., xN has a low discrepancy.

Roughly speaking, the discrepancy of a sequence is low if the proportion of points in the sequence falling into an arbitrary set B is close to proportional to the measure of B, as would happen on average (but not for particular samples) in the case of an equidistributed sequence. Specific definitions of discrepancy differ regarding the choice of B (hyperspheres, hypercubes, etc.) and how the discrepancy for every B is computed (usually normalized) and combined (usually by taking the worst value).

Low-discrepancy sequences are also called quasi-random or sub-random sequences, due to their common use as a replacement of uniformly distributed random numbers. The "quasi" modifier is used to denote more clearly that the values of a low-discrepancy sequence are neither random nor pseudorandom, but such sequences share some properties of random variables and in certain applications such as the quasi-Monte Carlo method their lower discrepancy is an important advantage.

Generation methods

Because any distribution of random numbers can be mapped onto a uniform distribution, and subrandom numbers are mapped in the same way, this article only concerns generation of subrandom numbers on a multidimensional uniform distribution.

From random numbers

Sequences of subrandom numbers can be generated from random numbers by imposing a negative correlation on those random numbers. One way to do this is to start with a set of random numbers  on

on  and construct subrandom numbers

and construct subrandom numbers  which are uniform on

which are uniform on  using:

using:

for

for  odd and

odd and  for

for  even.

even.

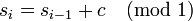

A second way to do it with the starting random numbers is to construct a random walk with offset 0.5 as in:

That is, take the previous subrandom number, add 0.5 and the random number, and take the result modulo 1.

For more than one dimension, Latin squares of the appropriate dimension can be used to provide offsets to ensure that the whole domain is covered evenly.

Additive.

One standard method for producing numbers that approximate random numbers is to use the recurrence relation:[1]

When  and

and  are both one this becomes an easy way to generate subrandom numbers:

are both one this becomes an easy way to generate subrandom numbers:

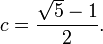

When  is an irrational number this never repeats. The value of

is an irrational number this never repeats. The value of  that produces the most even coverage of the domain [0,1) is:[2]

that produces the most even coverage of the domain [0,1) is:[2]

Another value that is nearly as good is:

In more than one dimension, separate subrandom numbers are needed for each dimension. In higher dimensions one set of values that can be used is the square roots of primes from two up, all taken modulo 1:

Halton sequence

In one dimension, the  th number

th number  of a Halton sequence is obtained by the following steps:

of a Halton sequence is obtained by the following steps:

1) Write  and a number in base

and a number in base  , where

, where  is some prime. (For example,

is some prime. (For example,  = 17 in base

= 17 in base  = 3 is 122.)

= 3 is 122.)

2) Reverse the digits and put a decimal point in front of the sequence (e.g.  base 3 =

base 3 =  ).

).

To extend this to more dimensions use a different prime for each dimension, typically  are used in turn.

are used in turn.

Sobol sequence

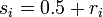

The Antonov–Saleev variant of the Sobol sequence generates numbers between zero and one directly as binary fractions of length  , from a set of

, from a set of  special binary fractions,

special binary fractions,  called direction numbers. The bits of the Gray code of

called direction numbers. The bits of the Gray code of  ,

,  , are used to select direction numbers. To get the Sobol sequence value

, are used to select direction numbers. To get the Sobol sequence value  take the exclusive or of the binary value of the Gray code of

take the exclusive or of the binary value of the Gray code of  with the appropriate direction number. The number of dimensions required affects the choice of

with the appropriate direction number. The number of dimensions required affects the choice of  .

.

Applications

Subrandom numbers have an advantage over pure random numbers in that they cover the domain of interest quickly and evenly. They have an advantage over purely deterministic methods in that deterministic methods only give high accuracy when the number of datapoints is pre-set whereas in using subrandom numbers the accuracy improves continually as more datapoints are added.

Two useful applications are in finding the characteristic function of a probability density function, and in finding the derivative function of a deterministic function with a small amount of noise. Subrandom numbers allow higher-order moments to be calculated to high accuracy very quickly.

Applications that don't involve sorting would be in finding the mean, standard deviation, skewness and kurtosis of a statistical distribution, and in finding the integral and global maxima and minima of difficult deterministic functions. Subrandom numbers can also be used for providing starting points for deterministic algorithms that only work locally, such as Newton–Raphson iteration.

Subrandom numbers can also be combined with search algorithms. A binary tree Quicksort-style algorithm ought to work exceptionally well because subrandom numbers flatten the tree far better than random numbers, and the flatter the tree the faster the sorting. With a search algorithm, subrandom numbers can be used to find the mode, median, confidence intervals and cumulative distribution of a statistical distribution, and all local minima and all solutions of deterministic functions.

low-discrepancy sequences in numerical integration

At least three methods of numerical integration can be phrased as follows. Given a set {x1, ..., xN} in the interval [0,1], approximate the integral of a function f as the average of the function evaluated at those points:

If the points are chosen as xi = i/N, this is the rectangle rule. If the points are chosen to be randomly (or pseudorandomly) distributed, this is the Monte Carlo method. If the points are chosen as elements of a low-discrepancy sequence, this is the quasi-Monte Carlo method. A remarkable result, the Koksma–Hlawka inequality (stated below), shows that the error of such a method can be bounded by the product of two terms, one of which depends only on f, and the other one is the discrepancy of the set {x1, ..., xN}.

It is convenient to construct the set {x1, ..., xN} in such a way that if a set with N+1 elements is constructed, the previous N elements need not be recomputed. The rectangle rule uses points set which have low discrepancy, but in general the elements must be recomputed if N is increased. Elements need not be recomputed in the Monte Carlo method if N is increased, but the point sets do not have minimal discrepancy. By using low-discrepancy sequences, the quasi-Monte Carlo method has the desirable features of the other two methods.

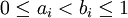

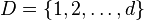

Definition of discrepancy

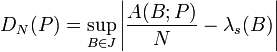

The discrepancy of a set P = {x1, ..., xN} is defined, using Niederreiter's notation, as

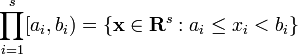

where λs is the s-dimensional Lebesgue measure, A(B;P) is the number of points in P that fall into B, and J is the set of s-dimensional intervals or boxes of the form

where  .

.

The star-discrepancy D*N(P) is defined similarly, except that the supremum is taken over the set J* of rectangular boxes of the form

where ui is in the half-open interval [0, 1).

The two are related by

Graphical examples

The points plotted below are the first 100, 1000, and 10000 elements in a sequence of the Sobol' type. For comparison, 10000 elements of a sequence of pseudorandom points are also shown. The low-discrepancy sequence was generated by TOMS algorithm 659.[3] An implementation of the algorithm in Fortran is available from Netlib.

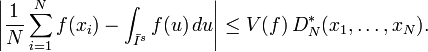

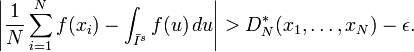

The Koksma–Hlawka inequality

Let Īs be the s-dimensional unit cube, Īs = [0, 1] × ... × [0, 1]. Let f have bounded variation V(f) on Īs in the sense of Hardy and Krause. Then for any x1, ..., xN in Is = [0, 1) × ... × [0, 1),

The Koksma-Hlawka inequality is sharp in the following sense: For any point set {x1,...,xN} in Is and any  , there is a function f with bounded variation and V(f)=1 such that

, there is a function f with bounded variation and V(f)=1 such that

Therefore, the quality of a numerical integration rule depends only on the discrepancy D*N(x1,...,xN).

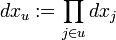

The formula of Hlawka-Zaremba

Let  . For

. For  we

write

we

write

and denote by  the point obtained from x by replacing the

coordinates not in u by

the point obtained from x by replacing the

coordinates not in u by  .

Then

.

Then

The  version of the Koksma–Hlawka inequality

version of the Koksma–Hlawka inequality

Applying the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality

for integrals and sums

to the Hlawka-Zaremba identity, we obtain

an  version of the Koksma–Hlawka inequality:

version of the Koksma–Hlawka inequality:

where

and

The Erdős–Turán–Koksma inequality

It is computationally hard to find the exact value of the discrepancy of large point sets. The Erdős–Turán–Koksma inequality provides an upper bound.

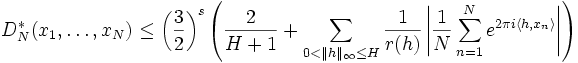

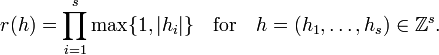

Let x1,...,xN be points in Is and H be an arbitrary positive integer. Then

where

The main conjectures

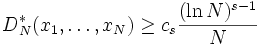

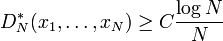

Conjecture 1. There is a constant cs depending only on the dimension s, such that

for any finite point set {x1,...,xN}.

Conjecture 2. There is a constant c's depending only on s, such that

for at least one N for any infinite sequence x1,x2,x3,....

These conjectures are equivalent. They have been proved for s ≤ 2 by W. M. Schmidt. In higher dimensions, the corresponding problem is still open. The best-known lower bounds are due to K. F. Roth.

The best known sequences

Constructions of sequences are known such that

where C is a certain constant, depending on the sequence. After Conjecture 2, these sequences are believed to have the best possible order of convergence. See also: van der Corput sequence, Halton sequences, Sobol sequences.

Lower bounds

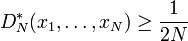

Let s = 1. Then

for any finite point set {x1, ..., xN}.

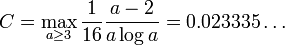

Let s = 2. W. M. Schmidt proved that for any finite point set {x1, ..., xN},

where

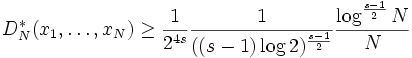

For arbitrary dimensions s > 1, K.F. Roth proved that

for any finite point set {x1, ..., xN}. This bound is the best known for s > 3.

Applications

- Integration

- Optimization

- Statistical sampling

References

- ↑ Donald E. Knuth The Art of Computer Programming Vol. 2, Ch. 3

- ↑ http://mollwollfumble.blogspot.com/, Subrandom numbers

- ↑ P. Bratley and B.L. Fox in ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software, vol. 14, no. 1, pp 88—100

- Josef Dick and Friedrich Pillichshammer, Digital Nets and Sequences. Discrepancy Theory and Quasi-Monte Carlo Integration, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-19159-3

- Kuipers, L.; Niederreiter, H. (2005), Uniform distribution of sequences, Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-45019-8

- Harald Niederreiter. Random Number Generation and Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1992. ISBN 0-89871-295-5

- Michael Drmota and Robert F. Tichy, Sequences, discrepancies and applications, Lecture Notes in Math., 1651, Springer, Berlin, 1997, ISBN 3-540-62606-9

- William H. Press, Brian P. Flannery, Saul A. Teukolsky, William T. Vetterling. Numerical Recipes in C. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, second edition 1992. ISBN 0-521-43108-5 (see Section 7.7 for a less technical discussion of low-discrepancy sequences)

- Quasi-Monte Carlo Simulations, http://www.puc-rio.br/marco.ind/quasi_mc.html

External links

- Collected Algorithms of the ACM (See algorithms 647, 659, and 738.)

- GNU Scientific Library Quasi-Random Sequences

- Quasi-random sampling subject to constraints at FinancialMathematics.Com

![{\frac {1}{N}}\sum _{{i=1}}^{N}f(x_{i})-\int _{{{\bar I}^{s}}}f(u)\,du=\sum _{{\emptyset \neq u\subseteq D}}(-1)^{{|u|}}\int _{{[0,1]^{{|u|}}}}{{\rm {disc}}}(x_{u},1){\frac {\partial ^{{|u|}}}{\partial x_{u}}}f(x_{u},1)dx_{u}.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/e/5/d/8e5d7af0e0a35594bf96d0f7f978de71.png)

![{{\rm {disc}}}_{{d}}(\{t_{i}\})=\left(\sum _{{\emptyset \neq u\subseteq D}}\int _{{[0,1]^{{|u|}}}}{{\rm {disc}}}(x_{u},1)^{2}dx_{u}\right)^{{1/2}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/1/0/c/c/10cc128f622efcd55660fba9fa8da06b.png)

![\|f\|_{{d}}=\left(\sum _{{u\subseteq D}}\int _{{[0,1]^{{|u|}}}}\left|{\frac {\partial ^{{|u|}}}{\partial x_{u}}}f(x_{u},1)\right|^{2}dx_{u}\right)^{{1/2}}.](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/7/f/0/f7f03d4caf9c2de0e11a0809171a9d15.png)