Lou Andreas-Salomé

| Lou Andreas-Salomé | |

|---|---|

Lou Andreas-Salomé | |

| Born |

Louise von Salomé 12 February 1861 Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died |

5 February 1937 (aged 75) Göttingen, Germany |

| Nationality | Russian |

Lou Andreas-Salomé (born Louise von Salomé or Luíza Gustavovna Salomé, Russian: Луиза Густавовна Саломе; 12 February 1861 – 5 February 1937) was a Russian-born psychoanalyst and author.[1] Her diverse intellectual interests led to friendships with a broad array of distinguished western thinkers, including Nietzsche, Freud, and Rilke.

Life

Early years

Lou Salomé was born in St. Petersburg to an army general and his wife. Salomé was their only daughter; she had five brothers. Although she would later be attacked by the Nazis as a "Finnish Jewess," her parents were actually of French Huguenot and Northern German descent.[2]

Seeking an education when she was seventeen Salomé persuaded the Dutch preacher Hendrik Gillot, twenty-five years her senior, to teach her theology, philosophy, world religions, and French and German literature. Gillot became so smitten with Salomé that he planned to divorce his wife and marry her. Salomé and her mother went to Zurich, so she could acquire a university education. The journey was also intended to be beneficial for Salomé's physical health; she was coughing up blood at this time.

Rée, Nietzsche and later life

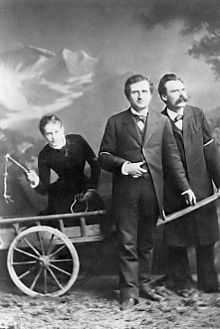

Salomé's mother took her to Rome, Italy when she was 21. At a literary salon in the city, Salomé became acquainted with Paul Rée, an author and compulsive gambler with whom she proposed living in an academic commune. After two months, the two became partners. On 13 May 1882, Rée's friend Friedrich Nietzsche joined the duo. Salomé would later (1894) write a study, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werken, of Nietzsche's personality and philosophy.[3] The three travelled with Salomé's mother through Italy and considered where they would set up their "Winterplan" commune. Arriving in Leipzig, Germany in October, Salomé and Rée separated from Nietzsche after a falling-out between Nietzsche and Salomé, in which Salomé believed that Nietzsche was desperately in love with her. In 1884 Salomé became acquainted with Helene von Druskowitz, the second woman to receive a philosophy doctorate in Zurich.

A fictional account of Salomé's relationship with Nietzsche is described in Irvin Yalom's novel, When Nietzsche Wept,[4] also in Lance Olsen's novel Nietzche's Kisses and the Mexican novel by Beatriz Rivas, The time without goddesses:La hora sin diosas,.[5] A biography in Swedish on Lou Salomé, which also covers her relationship with Paul Rée, Rainer Maria Rilke, Friedrich Nietzsche and Sigmund Freud was edited in 2008 on Mita bokförlag by the Swedish author Mirjam Tapper. The title of the book is "Den blonda besten hos Nietzsche - Lou Salomé".

Marriage and relationships

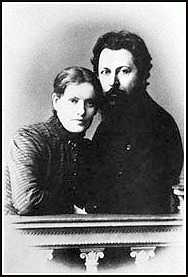

Salomé and Rée moved to Berlin and lived together until a few years before her celibate marriage [6] to linguistics scholar Friedrich Carl Andreas. Despite her opposition to marriage and her open relationships with other men, Salomé and Andreas remained married from 1887 until his death in 1930. The distress caused by Salomé's co-habitation with Andreas caused the morose Rée to fade from Salomé's life despite her assurances. Throughout her married life, she engaged in affairs or/and correspondence with the German journalist Georg Lebedour, the German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, on whom she wrote an analytical memoir,[7] the psychoanalysts Sigmund Freud and Viktor Tausk, among others. Accounts of many of these are given in her volume Lebensrückblick.

Her relationship with Rilke was particularly close. Salomé was fifteen years his senior. They met when he was 21, were lovers for several years and correspondents until Rilke's death; it was Salome who began calling him Rainer rather than René. She taught him Russian, in order to read Tolstoy (whom he would later meet) and Pushkin. She also introduced him to patrons and other people in the arts, remaining his advisor, confidante and muse throughout his adult life.[6]

Death

At the age of 74, Lou Andreas-Salomé ceased to work as a psychoanalyst. She had developed heart trouble, and in her weakened condition had to be treated many times in hospital. Her husband visited her daily; it was a difficult situation for the old man, who was himself quite ill. After a forty-year marriage marked by illness on both sides and long periods of mutual non-communication, the two grew closer. Sigmund Freud himself recognized this from afar, writing: "this only proves the permanence of the truth [of their relationship]." Friedrich Carl Andreas died of cancer in 1930. Lou Andreas-Salomé had to undergo a difficult cancer-related operation herself in 1935. On the evening of 5 February 1937 she died of uremia (kidney failure) in her sleep, at Göttingen. Her urn was laid to rest in her husband's grave in the Friedhof an der Groner Landstraße (Cemetery on Groner Landstrasse) in Göttingen. A memorial plaque on the newly renovated ground floor of her home, a street named "Lou-Andreas-Salomé-Weg" (Lou-Andreas-Salomé-Way), and the name of the institute for psychoanalysis and psychotherapy "(Lou-Andreas-Salomé Institut") commemorate the contributions of this former resident of Göttingen.

A few days before her death the Gestapo confiscated her library (according to other sources it was an SA group who destroyed the library, and shortly after her death). The pretense for this confiscation: She had been a colleague of Sigmund Freud's, had practiced "Jewish science", and had many books by Jewish authors in her library.

Work

Salomé was a prolific writer, and wrote several little-known novels, plays, and essays. She authored a "Hymn to Life" that so deeply impressed Nietzsche that he was moved to set it to music. Salomé's literary and analytical studies became such a vogue in Göttingen, the German town in which she lived her last years, that the Gestapo waited until shortly after her death by uremia in 1937 to "clean" her library from works by Jews (she was a pupil of Sigmund Freud and his associate in his creation of psychoanalysis). She was one of the first female psychoanalysts and one of the first women to write psychoanalytically on female sexuality, before Helene Deutsch, for instance in her essay on the anal-erotic (1916), an essay admired by Freud. However, she had written about the psychology of female sexuality before she ever met Freud, in her book Die Erotik (1911).

She wrote more than a dozen novels, such as Im Kampf um Gott, Ruth, Rodinka, Ma, "Fenitschka - eine Ausschweifung and also non-fiction studies such as Henrik Ibsens Frauengestalten (1892), a study of Ibsen's woman characters and a book on her friend Friedrich Nietzsche, Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werke, 1894.

She also edited a memoir on her lifelong close friend and onetime lover, the poet Rainer Maria Rilke, after his death in 1926. Among her works is also her Lebensrückblick, a book she wrote during her last years based on memories of her life as a free woman. In her memoirs, which were first published in their original German in 1951, she goes into depth about matters of her faith and her relationships.

Whoever reaches into a rosebush may seize a handful of flowers; but no matter how many one holds, it's only a small portion of the whole. Nevertheless, a handful is enough to experience the nature of the flowers. Only if we refuse to reach into the bush, because we can't possibly seize all the flowers at once, or if we spread out our handful of roses as if it were the whole of the bush itself—only then does it bloom apart from us, unknown to us, and we are left alone.[8]

Salomé is said to have remarked in her last days, "I have really done nothing but work all my life, work ... why?" And in her last hours, as if talking to herself, she is reported to have said, "If I let my thoughts roam I find no one. The best, after all, is death."[9]

A comprehensive and well researched account of Salomé's whole life and work is found in Angela Livingstone's "Lou Andreas Salomé".[10]

Notes

- ↑ Britannica biog

- ↑ Powell, Anthony (1994). Under Review: Further Writings on Writers, 1946-1990. University of Chicago Press. p. 440. ISBN 0-226-67712-5.

- ↑ Salomé, 2001

- ↑ Yalom I (1992) When Nietzsche Wept . Basic Books

- ↑ http://www.alfaguara.com/mx/ebook/la-hora-sin-diosas-3/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mark M. Anderson, "The Poet and the Muse", The Nation, July 3, 2006, p. 40-41.

- ↑ Andreas-Salomé, 2003

- ↑ Looking Back:The Memoirs of Lou Andreas-Salome Illustrated.

- ↑ Peters, 'My Sister, My Spouse', p. 300

- ↑ Angela Livingstone, Lou Andreas Salomé

References

- Astor, Dorian: Lou Andreas-Salomé, Gallimard, folio biographies, 2008. ISBN 978-2-07-033918-1

- Binion, R., Frau Lou: Nietzsche's Wayward Disciple, foreword by Walter Kaufmann, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1968

- Freud, S. and Lou Andreas-Salome: Letters, New York: Norton, 1985

- Livingstone, Angela: (1984). Lou Andreas Salomé: Her life and work. London: Gordon Fraser, 1984

- Michaud, Stéphane: Lou Andreas-Salomé. L'alliée de la vie. Seuil, Paris 2000. ISBN 2-02-023087-9

- Pechota Vuilleumier, Cornelia: 'O Vater, laß uns ziehn!' Literarische Vater-Töchter um 1900. Gabriele Reuter, Hedwig Dohm, Lou Andreas- Salomé. Olms, Hildesheim 2005. ISBN 3-487-12873-X

- Pechota Vuilleumier, Cornelia: Heim und Unheimlichkeit bei Rainer Maria Rilke und Lou Andreas-Salomé. Literarische Wechselwirkungen. Olms, Hildesheim 2010. ISBN 978-3-487-14252-4

- Peters, H. F., My Sister, My Spouse: A Biography of Lou Andreas-Salome, New York: Norton, 1962

- Salomé, Lou: The Freud Journal, Texas Bookman, 1996

- Salomé, Lou: Friedrich Nietzsche in seinen Werke, 1894; Eng., Nietzsche, tr. and ed. Siegfried Mandel, Champagin: University of Illinois Press Univ. of Illinois Press, 2001

- Salomé, Lou: You Alone Are Real to Me: Remembering Rainer Maria Rilke, tr. Angela von der Lippe, Rochester: BOA Editions, 2003

- Vollmann, William T., Friedrich Nietzsche: The Constructive Nihilist, The New York Times, August 14, 2005.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lou Andreas-Salomé. |

External links

|