Longitudinal static stability

Longitudinal static stability is the stability of an aircraft in the longitudinal, or pitching, plane under steady-flight conditions. This characteristic is important in determining whether a human pilot will be able to control the aircraft in the longitudinal plane without requiring excessive attention or excessive strength.[1]

Static stability

As any vehicle moves it will be subjected to minor changes in the forces that act on it, and in its speed.

- If such a change causes further changes that tend to restore the vehicle to its original speed and orientation, without human or machine input, the vehicle is said to be statically stable. The aircraft has positive stability.

- If such a change causes further changes that tend to drive the vehicle away from its original speed and orientation, the vehicle is said to be statically unstable. The aircraft has negative stability.

- If such a change causes no tendency for the vehicle to be restored to its original speed and orientation, and no tendency for the vehicle to be driven away from its original speed and orientation, the vehicle is said to be neutrally stable. The aircraft has zero stability.

For a vehicle to possess positive static stability it is not necessary for its speed and orientation to return to exactly the speed and orientation that existed before the minor change that caused the upset. It is sufficient that the speed and orientation do not continue to diverge but undergo at least a small change back towards the original speed and orientation.

Longitudinal stability

The longitudinal stability of an aircraft refers to the aircraft's stability in the pitching plane - the plane which describes the position of the aircraft's nose in relation to its tail and the horizon.[1] (Other stability modes are directional stability and lateral stability.)

If an aircraft is longitudinally stable, a small increase in angle of attack will cause the pitching moment on the aircraft to change so that the angle of attack decreases. Similarly, a small decrease in angle of attack will cause the pitching moment to change so that the angle of attack increases.[1]

The pilot's task

The pilot of an aircraft with positive longitudinal stability, whether it is a human pilot or an autopilot, has an easy task to fly the aircraft and maintain the desired pitch attitude which, in turn, makes it easy to control the speed, angle of attack and fuselage angle relative to the horizon. The pilot of an aircraft with negative longitudinal stability has a more difficult task to fly the aircraft. It will be necessary for the pilot devote more effort, make more frequent inputs to the elevator control, and make larger inputs, in an attempt to maintain the desired pitch attitude.[1]

Most successful aircraft have positive longitudinal stability, providing the aircraft's center of gravity lies within the approved range. Some acrobatic and combat aircraft have low-positive or neutral stability to provide high maneuverability. Some advanced aircraft have a form of low-negative stability called relaxed stability to provide extra-high maneuverability.

Center of gravity

The longitudinal static stability of an aircraft is significantly influenced by the distance (moment arm or lever arm) between the centre of gravity (c.g.) and the aerodynamic centre of the airplane. The c.g. is established by the design of the airplane and influenced by its loading, as by payload, passengers, etc. The aerodynamic centre (a.c.) of the airplane can be located approximately by taking the algebraic sum of the plan-view areas fore and aft of the c.g. multiplied by their blended moment arms and divided by their areas, in a manner analogous to the method of locating the c.g. itself. In conventional aircraft, this point is aft of, but close to, the one-quarter-chord point of the wing. In unconventional aircraft, e.g. the Quickie, it is between the two wings because the aft wing is so large. The pitching moment at the a.c. is typically negative and constant.

The a.c. of an airplane typically does not change with loading or other changes; but the c.g. does, as noted above. If the c.g. moves forward, the airplane becomes more stable (greater moment arm between the a.c. and the c.g.), and if too far forward will cause the airplane to be difficult for the pilot to bring nose-up as for landing. If the c.g. is too far aft, the moment arm between it and the a.c. diminishes, reducing he inherent stability of the airplane and in the extreme going negative and rendering the airplane longitudinally unstable; see the diagram below.

Accordingly, the operating handbook for every airplane specifies the range over which the c.g. is permitted to move. Inside this range, the airplane is considered to be inherently stable, which is to say that it will self-correct longitudinal (pitch) disturbances without pilot input.[2]

Analysis

Near the cruise condition most of the lift force is generated by the wings, with ideally only a small amount generated by the fuselage and tail. We may analyse the longitudinal static stability by considering the aircraft in equilibrium under wing lift, tail force, and weight. The moment equilibrium condition is called trim, and we are generally interested in the longitudinal stability of the aircraft about this trim condition.

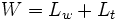

Equating forces in the vertical direction:

where W is the weight,  is the wing lift and

is the wing lift and  is the tail force.

is the tail force.

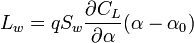

For a symmetrical airfoil at low angle of attack, the wing lift is proportional to the angle of attack:

where  is the wing area

is the wing area  is the (wing) lift coefficient,

is the (wing) lift coefficient,  is the angle of attack. The term

is the angle of attack. The term  is included to account for camber, which results in lift at zero angle of attack. Finally

is included to account for camber, which results in lift at zero angle of attack. Finally  is the dynamic pressure:

is the dynamic pressure:

where  is the air density and

is the air density and  is the speed.[3]

is the speed.[3]

Trim

The tailplane is usually a symmetrical airfoil, so its force is proportional to angle of attack, but in general, there will also be an elevator deflection to maintain moment equilibrium (trim). In addition, the tail is located in the flow field of the main wing, and consequently experiences a downwash, reducing the angle of attack at the tailplane.

For a statically stable aircraft of conventional (tail in rear) configuration, the tailplane force typically acts downward. In canard aircraft, both fore and aft planes are lifting surfaces. The fundamental requirement for static stability is that the aft surface have greater leverage in restoring a disturbance than the forward surface have in exacerbating it. This "leverage" is a product of moment arm from the center of gravity and surface area. Correctly balanced in this way, the partial derivative of pitching moment, w.r.t changes in angle of attack will be negative: pitch up to a larger angle of attack and the resultant pitching moment will tend to pitch the aircraft back down. (Here, pitch is used casually for the angle between the nose and the direction of the airflow; angle of attack.) This is the "stability derivative" d(M)/d(alpha), described below. Violations of this basic principle are exploited in some high performance combat aircraft to enhance agility; artificial stability is supplied by electronic means.

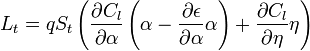

The tail force is, therefore:

where  is the tail area,

is the tail area,  is the tail force coefficient,

is the tail force coefficient,  is the elevator deflection, and

is the elevator deflection, and  is the downwash angle.

is the downwash angle.

Note that for a rear-tail configuration, the aerodynamic loading of the horizontal stabilizer (in  ) is less than that of the main wing, so the main wing should stall before the tail, ensuring that the stall is followed immediately by a reduction in angle of attack on the main wing, promoting recovery from the stall. (In contrast, in a canard configuration, the loading of the horizontal stabilizer is greater than that of the main wing, so that the horizontal stabilizer stalls before the main wing, again promoting recovery from the stall.)

) is less than that of the main wing, so the main wing should stall before the tail, ensuring that the stall is followed immediately by a reduction in angle of attack on the main wing, promoting recovery from the stall. (In contrast, in a canard configuration, the loading of the horizontal stabilizer is greater than that of the main wing, so that the horizontal stabilizer stalls before the main wing, again promoting recovery from the stall.)

There are a few classical cases where this favourable response was not achieved, notably some early T-tail jet aircraft. In the event of a very high angle of attack, the horizontal stabilizer became immersed in the downwash from the fuselage, causing excessive download on the stabilizer, increasing the angle of attack still further. The only way an aircraft could recover from this situation was by jettisoning tail ballast or deploying a special tail parachute. The phenomenon became known as 'deep stall'.

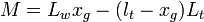

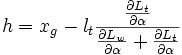

Taking moments about the center of gravity, the net nose-up moment is:

where  is the location of the center of gravity behind the aerodynamic center of the main wing,

is the location of the center of gravity behind the aerodynamic center of the main wing,  is the tail moment arm.

For trim, this moment must be zero. For a given maximum elevator deflection, there is a corresponding limit on center of gravity position at which the aircraft can be kept in equilibrium. When limited by control deflection this is known as a 'trim limit'. In principle trim limits could determine the permissible forwards and rearwards shift of the centre of gravity, but usually it is only the forward cg limit which is determined by the available control, the aft limit is usually dictated by stability.

is the tail moment arm.

For trim, this moment must be zero. For a given maximum elevator deflection, there is a corresponding limit on center of gravity position at which the aircraft can be kept in equilibrium. When limited by control deflection this is known as a 'trim limit'. In principle trim limits could determine the permissible forwards and rearwards shift of the centre of gravity, but usually it is only the forward cg limit which is determined by the available control, the aft limit is usually dictated by stability.

In a missile context 'trim limit' more usually refers to the maximum angle of attack, and hence lateral acceleration which can be generated.

Static stability

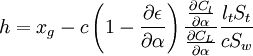

The nature of stability may be examined by considering the increment in pitching moment with change in angle of attack at the trim condition. If this is nose up, the aircraft is longitudinally unstable; if nose down it is stable. Differentiating the moment equation with respect to  :

:

Note:  is a stability derivative.

is a stability derivative.

It is convenient to treat total lift as acting at a distance h ahead of the centre of gravity, so that the moment equation may be written:

Applying the increment in angle of attack:

Equating the two expressions for moment increment:

The total lift  is the sum of

is the sum of  and

and  so the sum in the denominator can be simplified and written as the derivative of the total lift due to angle of attack, yielding:

so the sum in the denominator can be simplified and written as the derivative of the total lift due to angle of attack, yielding:

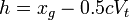

Where c is the mean aerodynamic chord of the main wing. The term:

is known as the tail volume ratio. Its rather complicated coefficient, the ratio of the two lift derivatives, has values in the range of 0.50 to 0.65 for typical configurations, according to Piercy. Hence the expression for h may be written more compactly, though somewhat approximately, as:

h is known as the static margin. For stability it must be negative. (However, for consistency of language, the static margin is sometimes taken as  , so that positive stability is associated with positive static margin.)

, so that positive stability is associated with positive static margin.)

Neutral point

A mathematical analysis of the longitudinal static stability of a complete aircraft (including horizontal stabilizer) yields the position of center of gravity at which stability is neutral. This position is called the neutral point.[1] (The larger the area of the horizontal stabilizer, and the greater the moment arm of the horizontal stabilizer about the aerodynamic center, the further aft is the neutral point.)

The static center of gravity margin (c.g. margin) or static margin is the distance between the center of gravity (or mass) and the neutral point. It is usually quoted as a percentage of the Mean Aerodynamic Chord. The center of gravity must lie ahead of the neutral point for positive stability (positive static margin). If the center of gravity is behind the neutral point, the aircraft is longitudinally unstable (the static margin is negative), and active inputs to the control surfaces are required to maintain stable flight. Some combat aircraft that are controlled by fly-by-wire systems are designed to be longitudinally unstable so they will be highly maneuverable. Ultimately, the position of the center of gravity relative to the neutral point determines the stability, control forces, and controllability of the vehicle.[1]

For a tailless aircraft  , the neutral point coincides with the aerodynamic center, and so for longitudinal static stability the center of gravity must lie ahead of the aerodynamic center.

, the neutral point coincides with the aerodynamic center, and so for longitudinal static stability the center of gravity must lie ahead of the aerodynamic center.

Longitudinal dynamic stability

An aircraft’s static stability is an important, but not sufficient, measure of its handling characteristics, and whether it can be flown with ease and comfort by a human pilot. In particular, the longitudinal dynamic stability of a statically stable aircraft will determine whether or not it is finally able to return to its original position.

See also

- Directional stability

- Flight dynamics

- Handling qualities

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Clancy, L.J. (1975) Aerodynamics, Chapter 16, Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- ↑ "The slope of the pitching moment curve [as a function of lift coefficient] has come to be the criterion of static longitudinal stability." Perkins and Hage, Airplane Performance, Stability, and Control, Wiley, 1949, p. 11-12

- ↑ Perkins and Hage, Airplane Performance, Stability, and Control, Wiley, NY, 1949, p. 11-12.

References

- Clancy, L.J. (1975), Aerodynamics, Pitman Publishing Limited, London. ISBN 0-273-01120-0

- Hurt, H.H. Jr, (1960), Aerodynamics for Naval Aviators Chapter 4, A National Flightshop Reprint, Florida.

- Irving, F.G. (1966), An Introduction to the Longitudinal Static Stability of Low-Speed Aircraft, Pergamon Press, Oxford, UK.

- McCormick, B.W., (1979), Aerodynamics, Aeronautics, and Flight Mechanics, Chapter 8, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York NY.

- Perkins, C.D. and Hage, R.E., (1949), Airplane Performance Stability and Control, Chapter 5, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York NY.

- Piercy, N.A.V. (1944), Elementary Aerodynamics, The English Universities Press Ltd., London.

- Stengel R F: Flight Dynamics. Princeton University Press 2004, ISBN 0-691-11407-2.