Logical effort

The method of logical effort, a term coined by Ivan Sutherland and Bob Sproull in 1991, is a straightforward technique used to estimate delay in a CMOS circuit. Used properly, it can aid in selection of gates for a given function (including the number of stages necessary) and sizing gates to achieve the minimum delay possible for a circuit.

Derivation of delay in a logic gate

Delay is expressed in terms of a basic delay unit, τ = 3RC, the delay of an inverter driving an identical inverter with no parasitic capacitance; the unitless number associated with this is known as the normalized delay. (Some authors prefer define the basic delay unit as the fanout of 4 delay—the delay of one inverter driving 4 identical inverters). The absolute delay is then simply defined as the product of the normalized delay of the gate, d, and τ:

In a typical 600-nm process τ is about 50 ps. For a 250-nm process, τ is about 20 ps. In modern 45 nm processes the delay is approximately 4 to 5 ps.

The normalized delay in a logic gate can be expressed as a summation of two primary factors: parasitic delay, p (which is an intrinsic delay of the gate and can be found by considering the gate driving no load), and stage effort, f (which is dependent on the load as described below). Consequently,

The stage effort is divided into two components: a logical effort, g, which is the ratio of the input capacitance of a given gate to that of an inverter capable of delivering the same output current (and hence is a constant for a particular class of gate and can be described as capturing the intrinsic properties of the gate), and an electrical effort, h, which is the ratio of the input capacitance of the load to that of the gate. Note that "logical effort" does not take the load into account and hence we have the term "electrical effort" which takes the load into account.The stage effort is then simply:

Combining these equations yields a basic equation that models the normalized delay through a single logic gate:

Procedure for calculating the logical effort of a single stage

CMOS inverters along the critical path are typically designed with a gamma equal to 2. In other words, the pFET of the inverter is designed with twice the width (and therefore twice the capacitance) as the nFET of the inverter, in order to get roughly the same pFET resistance as nFET resistance, in order to get roughly equal pull-up current and pull-down current.[1][2]

Choose sizes for all transistors such that the output drive of the gate is equal to the output drive of an inverter built from a size-2 PMOS and a size-1 NMOS.

The output drive of a gate is equal to the minimum – over all possible combinations of inputs – of the output drive of the gate for that input.

The output drive of a gate for a given input is equal to the drive at its output node.

The drive at a node is equal to the sum of the drives of all transistors which are enabled and whose source or drain is in contact with the node in question. A PMOS transistor is enabled when its gate voltage is 0. An NMOS transistor is enabled when its gate voltage is 1.

Once sizes have been chosen, the logical effort of the output of the gate is the sum of the widths of all transistors whose source or drain is in contact with the output node. The logical effort of each input to the gate is the sum of the widths of all transistors whose gate is in contact with that input node.

The logical effort of the entire gate is the ratio of its output logical effort to the sum of its input logical efforts.

Multistage logic networks

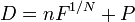

A major advantage of the method of logical effort is that it can quickly be extended to circuits composed of multiple stages. The total normalised path delay D can be expressed in terms of an overall path effort, F, and the path parasitic delay P (which is the sum of the individual parasitic delays):

The path effort is expressed in terms of the path logical effort G (the product of the individual logical efforts of the gates), and the path electrical effort H (the ratio of the load of the path to its input capacitance).

For paths where each gate drives only one additional gate (i.e. the next gate in the path),

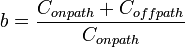

However, for circuits that branch, an additional branching effort, b, needs to be taken into account; it is the ratio of total capacitance being driven by the gate to the capacitance on the path of interest:

This yields a path branching effort B which is the product of the individual stage branching efforts; the total path effort is then

It can be seen that b = 1 for gates driving only one additional gate, fixing B = 1 and causing the formula to reduce to the earlier non-branching version.

Minimum delay

It can be shown that in multistage logic networks, the minimum possible delay along a particular path can be achieved by designing the circuit such that the stage logical efforts are equal. For a given combination of gates and a known load, B, G, and H are all fixed causing F to be fixed; hence the individual gates should be sized such that the individual stage efforts are

where N is the number of stages in the circuit.

Examples

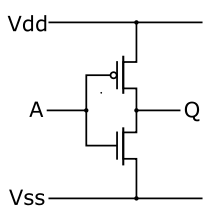

Delay in an inverter

By definition, the logical effort g of an inverter is 1. If the inverter drives an equivalent inverter, the electrical effort h is also 1.

The parasitic delay p of an inverter is also 1 (this can be found by considering the Elmore delay model of the inverter).

Therefore the total normalised delay of an inverter driving an equivalent inverter is

Delay in NAND and NOR gates

The logical effort of a two-input NAND gate is calculated to be g = 4/3 because a NAND gate with input capacitance 4 can drive the same current as the inverter can, with input capacitance 3. Similarly, the logical effort of a two-input NOR gate can be found to be g = 5/3. Due to the lower logical effort, NAND gates are typically preferred to NOR gates.

For larger gates, the logical effort is as follows:

| Number of Inputs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gate type | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | n |

| Inverter | 1 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| NAND | N/A |  |

|

|

|

|

| NOR | N/A |  |

|

|

|

|

The normalised parasitic delay of NAND and NOR gates is equal to the number of inputs.

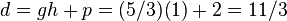

Therefore, the normalised delay of a two-input NAND gate driving an identical copy of itself (such that the electrical effort is 1) is

and for a two-input NOR gate, the delay is

References

- ↑ Bakos, Jason D. "Fundamentals of VLSI Chip Design". University of South Carolina. p. 23. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Dielen, M.; Theeuwen, J. F. M. (1987). An Optimal CMOS Structure for the Design of a Cell Library. p. 11.

Further reading

- Sutherland, Ivan E.; Sproull, Robert F.; Harris, David F. (1999). Logical Effort: Designing Fast CMOS Circuits. Morgan Kaufmann. ISBN 1-55860-557-6.

- Weste, Neil H. E.; Harris, David (2011). CMOS VLSI Design: A Circuits and Systems Perspective, 3rd Ed.. Pearson/Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-54774-8.