Lock-in amplifier

A lock-in amplifier (also known as a phase-sensitive detector) is a type of amplifier that can extract a signal with a known carrier wave from an extremely noisy environment (the signal-to-noise ratio can be -60 dB or even less[citation needed]). It is essentially a homodyne detector followed by a steep low pass filter, making it very narrow band. Practical lock-in amplifiers use mixing, through a frequency mixer, to convert the signal's phase and amplitude to a DC — actually a time-varying low-frequency — voltage signal.

The device is often used to measure phase shift, even when the signals are large and of high signal-to-noise ratio, and do not need further improvement.

Recovering signals at low signal-to-noise ratios requires a strong, clean reference signal the same frequency as the received signal. This is not the case in many experiments, so the instrument can recover signals buried in the noise only in a limited set of circumstances.

The lock-in amplifier is commonly believed to be invented by Princeton University physicist Robert H. Dicke who founded the company Princeton Applied Research (PAR) to market the product. However, in an interview with Martin Harwit, Dicke claims that even though he is often credited with the invention of the device, he believes he read about it in a review of scientific equipment written by Walter C Michels, a professor at Bryn Mawr College.[1] This was probably a 1941 paper by Michels and Curtis,[2] which in turn cites a 1934 paper by C. R. Cosens.[3]

Basic principles

Operation of a lock-in amplifier relies on the orthogonality of sinusoidal functions. Specifically, when a sinusoidal function of frequency ν is multiplied by another sinusoidal function of frequency μ not equal to ν and integrated over a time much longer than the period of the two functions, the result is zero. In the case when μ is equal to ν, and the two functions are in phase, the average value is equal to half of the product of the amplitudes.

In essence, a lock-in amplifier takes the input signal, multiplies it by the reference signal (either provided from the internal oscillator or an external source), and integrates it over a specified time, usually on the order of milliseconds to a few seconds. The resulting signal is a DC signal, where the contribution from any signal that is not at the same frequency as the reference signal is attenuated close to zero. The out-of-phase component of the signal that has the same frequency as the reference signal is also attenuated (because sine functions are orthogonal to the cosine functions of the same frequency), making a lock-in a phase-sensitive detector.

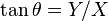

For a sine reference signal and an input waveform  , the DC output signal

, the DC output signal  can be calculated for an analog lock-in amplifier by:

can be calculated for an analog lock-in amplifier by:

where φ is a phase that can be set on the lock-in (set to zero by default).

If the averaging time T is large enough (e.g. much larger than the signal period) to suppress all unwanted parts like noise and the variations at twice the reference frequency, the output is

where  is the signal amplitude at the reference frequency and

is the signal amplitude at the reference frequency and  is the phase difference between the signal and reference.

is the phase difference between the signal and reference.

Many applications of the lock-in only require recovering the signal amplitude rather than relative phase to the reference signal. For a simple so called single phase lock-in-amplifier the phase difference is adjusted (usually manually) to zero to get the full signal.

More advanced, so called two phase lock-in-amplifiers have a second detector, doing the same calculation as before, but with an additional 90 degree phase shift. Thus one has two outputs:

is called the 'in-phase' component and

is called the 'in-phase' component and  the 'quadrature' component.

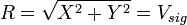

These two quantities represent the signal as a vector relative to the lock-in reference oscillator. By computing the magnitude (R) of the signal vector, the phase dependency is removed:

the 'quadrature' component.

These two quantities represent the signal as a vector relative to the lock-in reference oscillator. By computing the magnitude (R) of the signal vector, the phase dependency is removed:

.

.

The phase can be calculated from

.

.

Signal measurement in noisy environments

The essential idea in signal recovery is that noise tends to be spread over a wider spectrum, often much wider than the signal. In the simplest case of white noise, even if the root mean square of noise is 103 times as large as the signal to be recovered, if the bandwidth of the measurement instrument can be reduced by a factor much greater than 106 around the signal frequency, then the equipment can be relatively insensitive to the noise. In a typical 100 MHz bandwidth (e.g. an oscilloscope), a bandpass filter with width much narrower than 100 Hz would accomplish this. The averaging time of the lock-in-amplifier determines the bandwidth, and allows very narrow filters, less than 1 Hz if needed. However this comes at the price of a slow response to changes in the signal.

In summary, even when noise and signal are indistinguishable in the time domain, if the signal has a definite frequency band and there is no large noise peak within that band, noise and signal can be separated sufficiently in the frequency domain.

If the signal is either slowly varying or otherwise constant (essentially a DC signal), then 1/f noise typically overwhelms the signal. It may then be necessary to use external means to modulate the signal. For example, when detecting a small light signal against a bright background, the signal can be modulated either by a chopper wheel, acousto-optical modulator, photoelastic modulator at a large enough frequency so that 1/f noise drops off significantly, and the lock-in amplifier is referenced to the operating frequency of the modulator. In the case of an atomic force microscope, to achieve nanometer and piconewton resolution, the cantilever position is modulated at a high frequency, to which the lock-in amplifier is again referenced.

When the lock-in technique is applied, care must be taken to calibrate the signal, because lock-in amplifiers generally detect only the root-mean-square signal of the operating frequency. For a sinusoidal modulation, this would introduce a factor of  between the lock-in amplifier output and the peak amplitude of the signal, and a different factor for non-sinusoidal modulation.

between the lock-in amplifier output and the peak amplitude of the signal, and a different factor for non-sinusoidal modulation.

In the case of nonlinear systems, higher harmonics of the modulation-frequency appear. A simple example is the light of a conventional light bulb being modulated at twice the line frequency. Some lock-in-Amplifiers also allow separate measurements of these higher harmonics.

Furthermore, the response width (effective bandwidth) of detected signal depends on the amplitude of the modulation. Generally, linewidth/modulation function has a monotonically increasing, non-linear behavior.

References

the following citations cannot be searched because they require a private database unavailable to most people.

- ↑ http://www.aip.org/history/ohilist/4572.html

- ↑ Michels, W. C.; Curtis, N. L. (1941). "A Pentode Lock-In Amplifier of High Frequency Selectivity". Review of Scientific Instruments 12 (9): 444. Bibcode:1941RScI...12..444M. doi:10.1063/1.1769919.

- ↑ Cosens, C. R. (1934). "A balance-detector for alternating-current bridges". Proceedings of the Physical Society 46 (6): 818. doi:10.1088/0959-5309/46/6/310.

- Stutt, C.A. (March 1949). "Low-frequency spectrum of lock-in amplifiers". MIT Technical Report (MIT) (105): 1–18.

- Scofield, John H. (February 1994). "Frequency-domain description of a lock-in amplifier". American Journal of Physics (AAPT) 62 (2): 129–133. Bibcode:1994AmJPh..62..129S. doi:10.1119/1.17629.

- Jaquier, Pierre-Alain; Jaquier, Alain (March 1994). "Multiple-channel digital lock-in amplifier with PPM resolution". Review of Scientific Instruments (AIP) 65 (3): 747. Bibcode:1994RScI...65..747P. doi:10.1063/1.1145096.

- Wang, Xiaoyi (1990). "Sensitive digital lock-in amplifier using a personal computer". Review of Scientific Instruments (AIP) 61 (70): 1999. Bibcode:1990RScI...61.1999W. doi:10.1063/1.1141413.

- Wolfson, Richard (June 1991). "The lock-in amplifier: A student experiment". American Journal of Physics (AAPT) 59 (6): 569–572. Bibcode:1991AmJPh..59..569W. doi:10.1119/1.16824.

- Dixon, Paul K.; Wu, Lei (October 1989). "Broadband digital lock-in amplifier techniques". Review of Scientific Instruments (AIP) 60 (10): 3329. Bibcode:1989RScI...60.3329D. doi:10.1063/1.1140523.

- van Exter, Martin; Lagendijk, Ad (March 1986). "Converting an AM radio into a high-frequency lock-in amplifier in a stimulated Raman experiment". Review of Scientific Instruments (AIP) 57 (3): 390. Bibcode:1986RScI...57..390V. doi:10.1063/1.1138952.

- Probst, P. A.; Collet, B. (March 1985). "Low-frequency digital lock-in amplifier". Review of Scientific Instruments (AIP) 56 (3): 466. Bibcode:1985RScI...56..466P. doi:10.1063/1.1138324.

- Temple, Paul A. (1975). "An introduction to phase-sensitive amplifiers: An inexpensive student instrument". American Journal of Physics (AAPT) 43 (9): 801–807. Bibcode:1975AmJPh..43..801T. doi:10.1119/1.9690.

- Burdett, Richard (2005). "Amplitude Modulated Signals - The Lock-in Amplifier". Handbook of Measuring System Design (Wiley). ISBN 978-0-470-02143-9.

External links

- from Stanford Research Systems. Application note detailing how lock-in amplifiers work.

- Calculation of a modulated time dependent Lorentz signal and its line broadening due to the finite modulation by Lock-In Technique.

- Lock-in amplifier tutorial from Bentham Instruments. Comprehensive tutorial about the why and how of lock-in amplifiers.

- Lock-in Technical Notes Range of Technical and Applications notes describing the design of digital and analog lock-ins, and guide to their specifications from SIGNAL RECOVERY.

- PCSC-Lock-in Tool for data acquisition on acoustic chopping frequency using a computer sound card.

![U_{{{\mathrm {out}}}}(t)={\frac {1}{T}}\int _{{t-T}}^{t}{\sin \left[2\pi f_{{{\mathrm {ref}}}}\cdot s+\varphi \right]U_{{{\mathrm {in}}}}(s)}\;{\mathrm {d}}s](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/b/e/9/abe9fb178caf512414bc79f453af2b35.png)