Lobules of liver

| Lobules of liver | |

|---|---|

| |

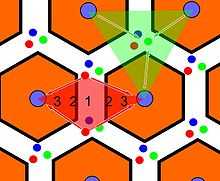

| The structure of the liver’s functional units or lobules. Blood enters the lobules through branches of the portal vein and hepatic artery proper, then flows through sinusoids. | |

| Latin | lobuli hepatis |

A hepatic lobule is a small division of the liver defined at the histological scale. It should not be confused with the anatomic lobes of the liver (caudate lobe, quadrate lobe, left lobe, and right lobe), or any of the functional lobe classification systems.

The two-dimensional microarchitecture of the liver can be viewed from multiple different perspectives:[1]

| Name | Shape | Model |

| classical lobule[2] | hexagonal; divided into concentric centrilobular, midzonal, periportal parts | anatomical |

| portal lobule[3] | triangular; centered around a portal triad | bile secretion |

| acinus [4] | elliptical or diamond-shaped; divided into zone I (periportal), zone II (transition zone), and zone III (pericentral) | blood flow and metabolic |

The term "hepatic lobule", without qualification, typically refers to the classical lobule.

Zones

From a metabolic perspective, the functional unit is the hepatic acinus (terminal acinus), each of which is centered on the line connecting two portal triads and extends outwards to the two adjacent central veins. The periportal zone I is nearest to the entering vascular supply and receives the most oxygenated blood, making it least sensitive to ischemic injury while making it very susceptible to viral hepatitis. Conversely, the centrilobular zone III has the poorest oxygenation, and will be most affected during a time of ischemia.[5]

Functionally, zone I hepatocytes are specialized for oxidative liver functions such as gluconeogenesis, β-oxidation of fatty acids and cholesterol synthesis, while zone III cells are more important for glycolysis, lipogenesis and cytochrome P-450-based drug detoxification.[6] This specialization is reflected histologically; the detoxifying zone III cells have the highest concentration of CYP2E1 and thus are most sensitive to NAPQI production in acetaminophen toxicity.[7] Other zonal injury patterns include zone I deposition of hemosiderin in hemochromatosis and zone II necrosis in yellow fever.[6]

References

- ↑ Cell and Tissue Structure at U. Va.

- ↑ Histology at OU 88_03

- ↑ Histology at OU 88_09a

- ↑ Histology at OU 88_09b

- ↑ B.R. Bacon, J.G. O'Grady, A.M. Di Bisceglie, J.R. Lake (2006). Comprehensive Clinical Hepatology. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 0-323-03675-9.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 E.R. Schiff, M.F. Sorrell, W.C. Maddrey, ed. (2007). Schiff's Diseases of the Liver, Tenth Edition. Lippincott William & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-6040-2.

- ↑ M.J. Burns, S.L. Friedman, A.M. Larson (2009). "Acetaminophen (paracetamol) poisoning in adults: Pathophysiology, presentation, and diagnosis". In D.S. Basow. UpToDate. Waltham, MA: UpToDate.

External links

- Liver Lobule development at LifeMap Discovery

- BU Histology Learning System: 15401loa

- Histology at siumed.edu

- Histology at okstate.edu

- Histology at webmd.idv.tw.

- UIUC Histology Subject 923

| |||||||||||||||||||||