Linear search

In computer science, linear search or sequential search is a method for finding a particular value in a list, that consists of checking every one of its elements, one at a time and in sequence, until the desired one is found.[1]

Linear search is the simplest search algorithm; it is a special case of brute-force search. Its worst case cost is proportional to the number of elements in the list; and so is its expected cost, if all list elements are equally likely to be searched for. Therefore, if the list has more than a few elements, other methods (such as binary search or hashing) will be faster, but they also impose additional requirements.

Analysis

For a list with n items, the best case is when the value is equal to the first element of the list, in which case only one comparison is needed. The worst case is when the value is not in the list (or occurs only once at the end of the list), in which case n comparisons are needed.

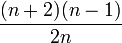

If the value being sought occurs k times in the list, and all orderings of the list are equally likely, the expected number of comparisons is

For example, if the value being sought occurs once in the list, and all orderings of the list are equally likely, the expected number of comparisons is  . However, if it is known that it occurs once, then at most n - 1 comparisons are needed, and the expected number of comparisons is

. However, if it is known that it occurs once, then at most n - 1 comparisons are needed, and the expected number of comparisons is

(for example, for n = 2 this is 1, corresponding to a single if-then-else construct).

Either way, asymptotically the worst-case cost and the expected cost of linear search are both O(n).

Non-uniform probabilities

The performance of linear search improves if the desired value is more likely to be near the beginning of the list than to its end. Therefore, if some values are much more likely to be searched than others, it is desirable to place them at the beginning of the list.

In particular, when the list items are arranged in order of decreasing probability, and these probabilities are geometrically distributed, the cost of linear search is only O(1). If the table size n is large enough, linear search will be faster than binary search, whose cost is O(log n).[1]

Application

Linear search is usually very simple to implement, and is practical when the list has only a few elements, or when performing a single search in an unordered list.

When many values have to be searched in the same list, it often pays to pre-process the list in order to use a faster method. For example, one may sort the list and use binary search, or build any efficient search data structure from it. Should the content of the list change frequently, repeated re-organization may be more trouble than it is worth.

As a result, even though in theory other search algorithms may be faster than linear search (for instance binary search), in practice even on medium sized arrays (around 100 items or less) it might be infeasible to use anything else. On larger arrays, it only makes sense to use other, faster search methods if the data is large enough, because the initial time to prepare (sort) the data is comparable to many linear searches [2]

Pseudocode

Forward iteration

This pseudocode describes a typical variant of linear search, where the result of the search is supposed to be either the location of the list item where the desired value was found; or an invalid location Λ, to indicate that the desired element does not occur in the list.

For each item in the list:

if that item has the desired value,

stop the search and return the item's location.

Return Λ.

In this pseudocode, the last line is executed only after all list items have been examined with none matching.

If the list is stored as an array data structure, the location may be the index of the item found (usually between 1 and n, or 0 and n−1). In that case the invalid location Λ can be any index before the first element (such as 0 or −1, respectively) or after the last one (n+1 or n, respectively).

If the list is a simply linked list, then the item's location is its reference, and Λ is usually the null pointer.

Recursive version

Linear search can also be described as a recursive algorithm:

LinearSearch(value, list)

if the list is empty, return Λ;

else

if the first item of the list has the desired value, return its location;

else return LinearSearch(value, remainder of the list)

Searching in reverse order

Linear search in an array is usually programmed by stepping up an index variable until it reaches the last index. This normally requires two comparison instructions for each list item: one to check whether the index has reached the end of the array, and another one to check whether the item has the desired value. In many computers, one can reduce the work of the first comparison by scanning the items in reverse order.

Suppose an array A with elements indexed 1 to n is to be searched for a value x. The following pseudocode performs a forward search, returning n + 1 if the value is not found:

Set i to 1.

Repeat this loop:

If i > n, then exit the loop.

If A[i] = x, then exit the loop.

Set i to i + 1.

Return i.

The following pseudocode searches the array in the reverse order, returning 0 when the element is not found:

Set i to n.

Repeat this loop:

If i ≤ 0, then exit the loop.

If A[i] = x, then exit the loop.

Set i to i − 1.

Return i.

Most computers have a conditional branch instruction that tests the sign of a value in a register, or the sign of the result of the most recent arithmetic operation. One can use that instruction, which is usually faster than a comparison against some arbitrary value (requiring a subtraction), to implement the command "If i ≤ 0, then exit the loop".

This optimization is easily implemented when programming in machine or assembly language. That branch instruction is not directly accessible in typical high-level programming languages, although many compilers will be able to perform that optimization on their own.

Using a sentinel

Another way to reduce the overhead is to eliminate all checking of the loop index. This can be done by inserting the desired item itself as a sentinel value at the far end of the list, as in this pseudocode:

Set A[n + 1] to x.

Set i to 1.

Repeat this loop:

If A[i] = x, then exit the loop.

Set i to i + 1.

Return i.

With this stratagem, it is not necessary to check the value of i against the list length n: even if x was not in A to begin with, the loop will terminate when i = n + 1. However this method is possible only if the array slot A[n + 1] exists but is not being otherwise used. Similar arrangements could be made if the array were to be searched in reverse order, and element A(0) were available.

Although the effort avoided by these ploys is tiny, it is still a significant component of the overhead of performing each step of the search, which is small. Only if many elements are likely to be compared will it be worthwhile considering methods that make fewer comparisons but impose other requirements.

Linear search on an ordered list

For ordered lists that must be accessed sequentially, such as linked lists or files with variable-length records lacking an index, the average performance can be improved by giving up at the first element which is greater than the unmatched target value, rather than examining the entire list.

If the list is stored as an ordered array, then binary search is almost always more efficient than linear search as with n > 8, say, unless there is some reason to suppose that most searches will be for the small elements near the start of the sorted list.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Knuth, Donald (1997). "Section 6.1: Sequential Searching,". Sorting and Searching. The Art of Computer Programming 3 (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 396–408. ISBN 0-201-89685-0.

- ↑ Horvath, Adam. "Binary search and linear search performance on the .NET and Mono platform". Retrieved 19 April 2013.

![{\begin{cases}n&{\mbox{if }}k=0\\[5pt]\displaystyle {\frac {n+1}{k+1}}&{\mbox{if }}1\leq k\leq n.\end{cases}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/3/6/d/6/36d628251be0345ae70c85234e078031.png)