Line element

In geometry, the line element or length element can most generally be thought of as the change in a position vector in an affine space expressing the change of the arc length. An easy way of visualizing this relationship is by parameterizing the given curve by Frenet–Serret formulas. As such, a line element is then naturally a function of the metric, and can be related to the curvature tensor. It is usually denoted by s or ℓ, and differentials of this are then written ds or dℓ.

Line elements are used in physics, especially in theories of gravitation (most notably general relativity) where spacetime is modelled as a curved manifold with a metric. For example, if a massive object causes some curvature in spacetime, the trajectory of an object with negligible mass over that curvature would follow the line element according to the geodesic equation.[1]

General formulation

Definition using metric

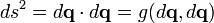

The coordinate-independent definition of the square of the line element ds in an n-dimensional metric space is:[2]

where g is the metric tensor, · denotes inner product, and dq an infinitesimal displacement in the metric space.

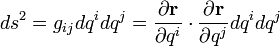

In n-dimensional general curvilinear coordinates q = (q1, q2, q3...qn), the square of arc length is:[3][4]

where the indices i and j take values 1, 2, 3 ... n. Common examples of metric spaces include three-dimensional space (no inclusion of time coordinates), and indeed four-dimensional spacetime. The metric is the origin of the line element, in addition to the surface and volume elements etc.

Total arc length

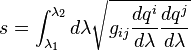

By parameterizing a curve with a parameter λ, so that q(λ), the arc length of the curve between the points q(λ1) and q(λ2) is the integral:[5]

Line elements in Euclidean space

Following are examples of how the line elements are found from the metric.

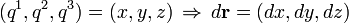

Cartesian coordinates

The simplest line element is in Cartesian coordinates - in which case the metric is just the Kronecker delta:

(here i, j = 1, 2, 3 for space) or in matrix form (i denotes row, j denotes column):

The general curvilinear coordinates reduce to Cartesian coordinates:

so

Orthogonal curvilinear coordinates

For all orthogonal coordinates the metric is given by:[6]

where

for i = 1, 2, 3 are scale factors, so the square of the line element is:

Some examples of line elements in these coordinates are below.[7]

Coordinate system (q1, q2, q3) Metric Line element Plane polars (r, θ) ![[g_{{ij}}]={\begin{pmatrix}1&0\\0&r^{2}\\\end{pmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/e/e/a/0/eea001d30f85af38488c2866a4954d57.png)

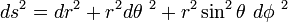

Spherical polars (r, θ, φ) ![[g_{{ij}}]={\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\0&r^{2}&0\\0&0&r^{2}\sin ^{2}\theta \\\end{pmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/c/d/2/9cd22b5d04f6c323d20b0c63ec67b600.png)

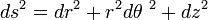

Cylindrical polars (r, θ, z) ![[g_{{ij}}]={\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\0&r^{2}&0\\0&0&1\\\end{pmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/8/4/1/e/841efaac224513f5036726b39374f06d.png)

General curvilinear coordinates

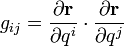

In general curvilinear coordinates, the metric has elements given by:[8]

so the square of the line element is

Line elements in 4d spacetime

Minkowskian spacetime

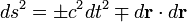

The Minkowski metric is:[9][10]

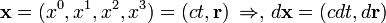

where one sign or the other is chosen, both conventions are used. This applies only for flat spacetime. The coordinates are given by the 4-position:

so the line element is:

General spacetime

The coordinate-independent definition of the square of the line element ds in spacetime is:[11]

In terms of coordinates:

where for this case the indices α and β run over 0, 1, 2, 3 for spacetime.

This is the invariant interval - the measure of separation between two arbitrarily close events in spacetime. In special relativity it is invariant under Lorentz transformations; in general relativity it is invariant under arbitrary invertible differentiable coordinate transformations.

See also

- Covariance and contravariance of vectors

- First fundamental form

- List of integration and measure theory topics

- Metric tensor

- Ricci calculus

- Raising and lowering indices

References

- ↑ Gravitation, J.A. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne, W.H. Freeman & Co, 1973, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

- ↑ Tensor Calculus, D.C. Kay, Schaum’s Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 1988, ISBN 0-07-033484-6

- ↑ Vector Analysis (2nd Edition), M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipcshutz, D. Spellman, Schaum’s Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 2009, ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7

- ↑ An introduction to Tensor Analysis: For Engineers and Applied Scientists, J.R. Tyldesley, Longman, 1975, ISBN 0-582-44355-5

- ↑ Vector Analysis (2nd Edition), M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipcshutz, D. Spellman, Schaum’s Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 2009, ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7

- ↑ Vector Analysis (2nd Edition), M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipcshutz, D. Spellman, Schaum’s Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 2009, ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7

- ↑ Tensor Calculus, D.C. Kay, Schaum’s Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 1988, ISBN 0-07-033484-6

- ↑ Vector Analysis (2nd Edition), M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipcshutz, D. Spellman, Schaum’s Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 2009, ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7

- ↑ Relativity DeMystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (USA), 2006, ISBN 0-07-145545-0

- ↑ Gravitation, J.A. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne, W.H. Freeman & Co, 1973, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

- ↑ Gravitation, J.A. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne, W.H. Freeman & Co, 1973, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

![[g_{{ij}}]={\begin{pmatrix}1&0&0\\0&1&0\\0&0&1\end{pmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/d/0/c/e/d0ce0720564b22fb94a8dc23f336afd5.png)

![[g_{{ij}}]={\begin{pmatrix}h_{1}^{2}&0&0\\0&h_{2}^{2}&0\\0&0&h_{3}^{2}\end{pmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/5/c/7/c5c7de68cd25b61bc7704b78e8bc1a17.png)

![[g_{{ij}}]={\begin{pmatrix}\pm 1&0&0&0\\0&\mp 1&0&0\\0&0&\mp 1&0\\0&0&0&\mp 1\\\end{pmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/f/1/6/cf169beef83be9025c8057068a706784.png)