Lindahl tax

A Lindahl tax is a form of taxation in which individuals pay for the provision of a public good according to their marginal benefits. So each individual pays according to his/her marginal benefit derived from the public good. e.g. If A loves scenic beauty and likes to be close to nature he might be ready to pay 5 dollars per day for sitting in a park, whereas a college student who does not visit the park very often will not be ready to pay so much, but might agree to pay 1 dollar. So a person who values the good more pays more.

Lindahl taxes are sometimes known as benefit taxes. A Lindahl equilibrium is a state of economic equilibrium under such a tax. Individuals in a society have different preferences based on their nature, personal choice etc. So an individual's willingness to pay for a public good is a function of many factors, like income, preference etc. So a student will want to pay just 1 dollar for entering a museum but a business man will be ready to pay 10 dollars for the same museum. So in such cases the problem of supply of the public good, at optimal levels arises. Lindahl taxation is a solution for this problem.[1]

Definition

A Lindahl tax is an individual share of the collective tax burden of an economy.[2] The optimal level of a public good is that quantity at which the willingness to pay for one more unit of the good, taken in totality for all the individuals is equal to the marginal cost of supplying that good. Lindahl tax is the optimal quantity times the willingness to pay for one more unit of that good at this quantity.[3]

Lindahl equilibrium

A Lindahl equilibrium is a method for finding the optimum level for the supply of public goods or services.This idea was given by Erik Lindahl in 1919. The Lindahl equilibrium happens when the total per-unit price paid by each individual equals the total per unit cost of the public good. The Lindahl equilibrium is Pareto efficient and it can be proved that an equilibrium exists for different environments.[4]

Lindahl equilibrium describes how efficiency can be sustained in an economy with personalised prices. Johansen (1963) gave the complete interpretation of the concept of "Lindahl equilibrium." The basic assumption of this concept is that every household's consumption decision is based on the share of the cost they must provide for the supply of the particular public good.[5]

The importance of Lindahl equilibrium is that it fulfills the Samuelson rule and is therefore said to be pareto efficient, despite the existence of public goods. It also demonstrates how efficiency can be reached in an economy with public goods by the use of personalised prices. The personalised prices equate the individual valuation for a public good to the cost of the public good.[6]

Background

Erik Lindahl was deeply influenced by his professor and mentor Knut Wicksell and proposed a method for financing public goods in order to show that consensus politics is possible. As people are different in nature, their preferences are different, and consensus requires each individual to pay a somewhat different tax for every service, or good that he consumes. If each person's tax price is set equal to the marginal benefits received at the ideal service level, each person is made better off by provision of the public good and may accordingly agree to have that service level provided.

Problem with Lindahl taxation

| Part of a series on Government |

| Public finance |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Reform |

Lindahl pricing and taxation requires the knowledge of the demand functions for each individual for all private and public goods.When information about marginal benefits is available only from the individuals themselves, they tend to under report their valuation for a particular good, this gives rise to a "preference revelation problem." Each individual can lower his tax cost by under reporting his benefits derived from the public good or service. This informational problem shows that survey-based Lindahl taxation is not incentive compatible. Incentives to understate or under report one's true benefits under Lindahl taxation resemble those of a Prisoner's dilemma, and people will be inclined to under report their demands for the public goods or service.

Preference revelation mechanisms can be used to solve that problem, although none of these have been shown to completely address the problem. Among others the Vickrey–Clarke–Groves mechanism is an example of this, ensuring true values are revealed and that a public good is provided only when it should be.[7] The allocation of cost is taken as given and the consumers will report their net benefits (benefits-cost). The public good will be provided if the sum of the net benefits of all consumers is positive. If the public good is provided side payments will be made reflecting the fact that truth telling is costly. The side payments internalize the net benefit of the public good to other players. The side payments must be financed from outside the mechanism. In reality these preference revelation mechanisms are difficult to implement as the size of the population makes it costly both in terms of money and time.[8]

Demand revelation

The Demand Revelation theory uses the Clarke tax or pivot mechanism, to ensure that individuals will consider the fact that their choices have a social cost on the social outcome, thus ensuring that they truthfully reveal their preferences,and hence overcoming the free rider problem of public goods provisioning.[9][10]

Revealed preference theory

It is an economic theory of consumption, given by Samuelson, it is a method of observing people's preferences and purchasing power.[11] If a consumer purchases one commodity instead of the other, the consumer reveals his preference for that good. Hence the good is said to be revealed preferred over the other.

The main idea of the theorem is that when an individual spends his entire income on a good, the demand behaviour of the person is in accordance with the Samuelson's Weak Axiom of Revealed Preference.[12]

Lindahl tax and Pareto optimality

A very important question is that whether a Lindahl tax is a Pareto Optimal equilibrium? A Pareto Optimal allocation happens with public goods when the total of the marginal rates of substitution (MRS) equals the marginal rate of transformation (MRT). So if it can be shown that this holds true in a Lindahl equilibrium, it can be conveniently said that it is Pareto Optimal. This can be shown by following the following steps:

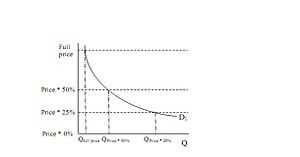

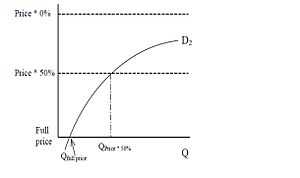

We take a demand curve for a public good. The less the price of the public good, the more will X want to consume. Let the horizontal line (dashed) be the full price of the public good. Now here, the demand curve implies that X will demand very less. But what if instead of the price decreasing, the percentage of the price X has to pay decreases? Now X sees the price going down, so his demand for the good increases. Now lets consider the demand curve of another person, lets say Y. Y sees the vertical axis turned the other way around, with the full price on the bottom and percentage decreasing as you move upwards. Like X, Y will also demand more as his observed price goes down.[13]

Now as Y observes the price going down it also means that we move further up the vertical axis. Equilibrium is when both X and Y demand the equal amount of the good. This is possible only when the demand curves of both X and Y intersect each other. If a line is drawn over the price axis from that point of intersection, we get the percentage share for each person that is required to get that price. [13]

In the Lindahl tax scheme it is essential that the system should provide for a pareto optimal output of the public good. The other important condition is that the Lindahl tax scheme should connect the tax paid by an individual to the benefits he derives. This system kind of promotes justice. If the individual's tax payment is equivalent to the benefits received by him, and if this linkage is good enough then it leads to Pareto optimality.[14]

So it is observed that X is paying P*45% per unit, and Y is paying P*55% per unit, and the economy produces Q* units. This point is called the Lindahl equilibrium, and the corresponding prices are called Lindahl prices.

Mathematical representation

We assume that there are two goods in a n economy:the first one is a "public good," and the second is “everything else.” The price of the public good can be assumed to be Ppublic and the price of everything else can be Pelse.

- α*P(PUBLIC)/P(EVERY) = MRS(PERSON1)

This is just the usual price ratio/marginal rate of substitution deal the only change is that we multiply Ppublic by α to allow for the price adjustment to the public good. Similarly, Person 2 will choose his bundle such that:

- (1-ɑ)*P(PUBLIC)/P(EVERY)= MRS(PERSON2)

Now we have both individuals' utility maximizing. We know that in a competitive equilibrium, the marginal cost ratio (price ratio)should be equal to the marginal rate of transformation, or

- MC(PUBLIC)/MC(EVERY)=[P(PUBLIC)/P(EVERY)]=MRT

Issues

Lindahl prices do face some serious drawbacks. First, individual demand curves, and thus individual preferences, are not easily known. Due to the free-rider problem, people have the incentive to hide their true preferences and thus their marginal valuation (However, mechanism design of Groves, which is strongly individually incentive compatible, and Vickrey auctions could be used to overcome this problem).

A second drawback to Lindahl prices is that they may be unfair. Consider a television broadcast antenna that is arbitrarily placed in an area. Those living near the antenna will receive a clear signal while those living farther away will receive a less clear signal. Those living close to the antenna will have a relatively low marginal value for additional wattage (thus paying a lower Lindahl price) compared to those living farther away (thus paying a higher Lindahl price).[15]

See also

|

- Lindahl, Erik

- Public choice theory

- Public finance

- Samuelson condition

- Taxation

- Tax choice

References

- ↑ http://www.saylor.org/site/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/ECON305-2.2.5-Lindahl-Handout-FINAL.pdf

- ↑ http://www.answers.com/topic/lindahl-equilibrium

- ↑ Equity: In Theory and Practice, p. 103.

- ↑ http://www.u.arizona.edu/~mwalker/11_PublicGoods/LindahlEquilibrium.pdf

- ↑ http://www.jstor.org/stable/2525312

- ↑ Myles, Gareth. ISBN 978-0-262-12127-9. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://www.enotes.com/topic/Lindahl_tax

- ↑ Backhaus, Jürgen Georg;, Wagner, Richard E. (2004). Handbook of Public Finance. ISBN 978-1-4020-7863-7.

- ↑ Revelation, Demand. "Demand Revelation". Economic Theory. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ↑ Fred Foldvary on Demand Revelation: Better than Voting

- ↑ Revealed Preference Definition

- ↑ Theory, Revealed Preference. "Revealed Preference theory". Microeconomics. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 http://www.stanford.edu/~sandersn/130A/Lindahl.pdf

- ↑ Welfare Economics and Social Choice Theory, p. 169.

- ↑ http://www.stanford.edu/~jay/micro_class/lecture19.pdf

- Foley, Duncan K. (1970), "Lindahl's Solution and the Core of an Economy with Public Goods", Econometrica 38 (1): 66–72, doi:10.2307/1909241.

- "Public Economics" by Gareth D. Myles (October 2001)

- Laffont, Jean-Jacques (1988). 0-262-12127-1&id=O5MnAQAAIAAJ "2.4 Lindahl equilibrium, 2.5.3 Majority voting or the law of the median voter". Fundamentals of public economics. MIT. pp. 41–43, 51–53. ISBN 978-0-262-12127-9, 978-0-262-12127-9 Check

|isbn=value (help). - Lindahl, Erik (1958) [1919], "Just taxation—A positive solution", in Musgrave, R. A.; Peacock, A. T., Classics in the Theory of Public Finance, London: Macmillan.

- Salanié, Bernard (2000). "5.2.3 The Lindahl equilibrium". Microeconomics of market failures (English translation of the (1998) French Microéconomie: Les défaillances du marché (Economica, Paris) ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 74–75. ISBN 0-262-19443-0, 978-0-262-19443-3 Check

|isbn=value (help). - Starrett, David A. (1988). "5 Planning mechanisms (pp. 65–72), 16 Practical methods for large project evaluation (Groves–Clarke mechanism, pp. 270–271)". Foundations of public economics. Cambridge economic handbooks XVI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 65–72, 270–271.