Library of Congress

| Library of Congress | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Flag of the Library of Congress [citation needed] | |

| Established | 1800 |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′19″N 77°00′17″W / 38.88861°N 77.00472°WCoordinates: 38°53′19″N 77°00′17″W / 38.88861°N 77.00472°W |

| Branches | N/A |

| Collection | |

| Size |

22,765,967 catalogued books in the Library of Congress Classification system; 5,600 incunabula (books printed before 1500), monographs and serials, music, bound newspapers, pamphlets, technical reports, and other printed material; and 109,029,796 items in the nonclassified (special) collections: 151,785,778 total Items[1] |

| Access and use | |

| Circulation | Library does not publicly circulate |

| Population served | 541 members of the United States Congress, their staff, and members of the public |

| Other information | |

| Budget | $613,496,414[1] |

| Director | James H. Billington (Librarian of Congress) |

| Staff | 3,597[1] |

| Website | www.loc.gov |

The Library of Congress is the research library of the United States Congress, the de facto national library of the United States of America, and the oldest federal cultural institution in the United States. Located in four buildings in Washington, D.C., as well as the Packard Campus[2] in Culpeper, Virginia, it is the second largest library in the world by shelf space and number of books, the largest being The British Library.[3] The head of the Library is the Librarian of Congress, currently James H. Billington.

The Library of Congress was instituted for the Congress of the United States when it moved in April 1800, after sitting for eleven years in the temporary capitals of New York City and Philadelphia and occupied the unfinished United States Capitol, at the beginning in the first completed north Senate wing. Later the south wing for the House of Representatives was constructed, leaving a covered wooden walkway between the two halves where the future central section, rotunda and dome would be placed. The small Congressional Library was housed in the United States Capitol for most of the 19th century until the early 1890s. Most of the original collection had been destroyed by the disastrous fire during the War of 1812 after the crushing defeat at the Battle of Bladensburg to the northeast of the Capital. The fire was purposely set by the invading British Army under the command of Gen. Robert Ross (1766-1814), and the infamous Vice Admiral George Cockburn (1772-1853), in August 1814. Their troops set fire to the unfinished rough village of the National Capital, burning the "President's House" (or "Executive Mansion", later known as the "White House" following a whitewashing/painting after the fire), The Capitol (also then called "Congress House"), the Post Office, small buildings surrounding the "President's House" for the War, State, Navy and Treasury Departments, and the waterfront Washington Navy Yard—all except the Patent Office with its invaluable collections of diagrams, models and scientific papers, which was spared on pleas of the Architect of the Capitol, Dr. William Thornton (1759-1828). The British also destroyed the offices of a Washington newspaper and its printing presses and cases of type, in revenge for its "slanderous stories". The Burning of Washington was an act of calculated revenge for the burning the previous year by American troops of the British/Canadian capital town of York (now Toronto).

After the war, in 1815, former 3rd President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) sold 6,487 books (his entire personal collection) from his estate of Monticello near Charlottesville, Virginia to the Congress of the United States and the Nation for the reconstituting of a new Library of Congress.[4][5]

After a period of decline during the mid-19th century, another disaster of fire struck the Library in 1851, in its Capitol chambers, again destroying a large amount of the collection, including many of Jefferson's books. The Library of Congress then began to grow rapidly in both size and importance after the American Civil War and a campaign to purchase replacement copies for volumes that had been burned from other sources, collections and libraries (which had begun to speckle throughout the burgeoning U.S.A.). The Library received the right of transference of all copyrighted works to have two copies deposited of books, maps, illustrations and diagrams printed in the United States. It also began to increase its collections of British (second largest publishers) and European works and then of works published throughout the English-speaking world.

This development culminated in the construction during 1888-1894 of a separate, expansive library building across the street to the southeast from The Capitol. This building was in the ""Beaux Arts" architecture style with fine decorations, murals, paintings, marble halls, columns and steps, carved hardwoods and a stained glass dome—all on a scale to match the magnificence of The Capitol itself. Several stories underground of steel and cast iron "stacks" were built beneath the "massive pile". Fire-proofing precautions were built in, so far as could be done in that era before piped sprinklers, portable fire extinguishers and electronic sensor technology.

During the continued more rapid expansion of the 20th century, the Library of Congress assumed a preeminent public role, becoming a "library of last resort" and expanding its mission for the benefit of researcher, scholars and the American people.

The Library's primary mission is researching inquiries made by members of Congress through the establishment of a "Congressional Research Service", established 1914. Although it is open to the public, only Library employees, Senators, Representatives as Members of Congress, Supreme Court justices, Secretaries of Executive Departments in the President's Cabinet, and other high-ranking government officials may check out books and materials. As the de facto national library of the United States, the Library of Congress promotes literacy and American literature through projects such as the American Folklife Center, American Memory, Center for the Book and Poet Laureate.

History

Origins and Jefferson's contribution (1800–1851)

The Library of Congress was established on April 24, 1800, when President John Adams signed an Act of Congress providing for the transfer of the seat of government from Philadelphia to the new capital city of Washington. Part of the legislation appropriated $5,000 "for the purchase of such books as may be necessary for the use of Congress ..., and for fitting up a suitable apartment for containing them...." Books were ordered from London and the collection, consisting of 740 books and 3 maps, was housed in the new Capitol.[6]

Thomas Jefferson played an important role in the Library's early formation, signing into law on January 26, 1802, the first law establishing the structure of the Library of Congress. The law established the presidentially appointed post of Librarian of Congress and a Joint Committee on the Library to regulate and oversee the Library, as well as giving the president and vice president the ability to borrow books.[6] The Library of Congress was destroyed in August 1814, when invading British Regulars set fire to the Capitol building and the small library of 3,000 volumes within.[6]

Within a month, former President Jefferson offered his personal library[7][8] as a replacement. Jefferson had spent 50 years accumulating a wide variety of books, including ones in foreign languages and volumes of philosophy, science, literature, architecture and other topics not normally viewed as part of a legislative library, such as cookbooks, writing that, "I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer." In January 1815, Congress accepted Jefferson's offer, appropriating $23,950 to purchase his 6,487 books.[6]

Weakening (1851–1865)

The antebellum period was difficult for the Library. During the 1850s the Smithsonian Institution's librarian Charles Coffin Jewett aggressively tried to move that organization towards becoming the United States' national library. His efforts were blocked by the Smithsonian's Secretary Joseph Henry, who advocated a focus on scientific research and publication and favored the Library of Congress' development into the national library. Henry's dismissal of Jewett in July 1854 ended the Smithsonian's attempts to become the national library, and in 1866 Henry transferred the Smithsonian's forty thousand-volume library to the Library of Congress.[6]

On December 24, 1851 the largest fire in the Library's history destroyed 35,000 books, about two–thirds of the Library's 55,000 book collection, including two–thirds of Jefferson's original transfer.[6] Congress in 1852 quickly appropriated $168,700 to replace the lost books, but not for the acquisition of new materials. This marked the start of a conservative period in the Library's administration under Librarian John Silva Meehan and Joint Committee Chairman James A. Pearce, who worked to restrict the Library's activities.[6] In 1857, Congress transferred the Library's public document distribution activities to the Department of the Interior and its international book exchange program to the Department of State. Abraham Lincoln's political appointment of John G. Stephenson as Librarian of Congress in 1861 further weakened the Library; Stephenson's focus was on non-library affairs, including service as a volunteer aide-de-camp at the battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg during the American Civil War. By the conclusion of the war, the Library of Congress had a staff of seven for a collection of 80,000 volumes.[6] The centralization of copyright offices into the United States Patent Office in 1859 ended the Library's thirteen-year role as a depository of all copyrighted books and pamphlets.

Spofford's expansion (1865–1897)

A year before the Library's move to its new location, the Joint Library Committee held a session of hearings to assess the condition of the Library and plan for its future growth and possible reorganization. Spofford and six experts sent by the American Library Association, including future Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam and Melvil Dewey of the New York State Library, testified before the committee that the Library should continue its expansion towards becoming a true national library.[6] Based on the hearings and with the assistance of Senators Justin Morrill of Vermont and Daniel Voorhees of Indiana, Congress more than doubled the Library's staff from 42 to 108 and established new administrative units for all aspects of the Library's collection. Congress also strengthened the office of Librarian of Congress to govern the Library and make staff appointments, as well as requiring Senate approval for presidential appointees to the position.[6]

Post-reorganization (1897–1939)

The Library of Congress, spurred by the 1897 reorganization, began to grow and develop more rapidly. Spofford's successor John Russell Young, though only in office for two years, overhauled the Library's bureaucracy, used his connections as a former diplomat to acquire more materials from around the world, and established the Library's first assistance programs for the blind and physically disabled.[6] Young's successor Herbert Putnam held the office for forty years from 1899 to 1939, entering into the position two years before the Library became the first in the United States to hold one million volumes.[6] Putnam focused his efforts on making the Library more accessible and useful for the public and for other libraries. He instituted the interlibrary loan service, transforming the Library of Congress into what he referred to as a "library of last resort".[9] Putnam also expanded Library access to "scientific investigators and duly qualified individuals" and began publishing primary sources for the benefit of scholars.[6]

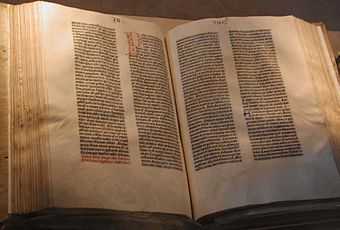

Putnam's tenure also saw increasing diversity in the Library's acquisitions. In 1903, he persuaded President Theodore Roosevelt to transfer by executive order the papers of the Founding Fathers from the State Department to the Library of Congress. Putnam expanded foreign acquisitions as well, including the 1904 purchase of a four-thousand volume library of Indica, the 1906 purchase of G. V. Yudin's eighty-thousand volume Russian library, the 1908 Schatz collection of early opera librettos, and the early 1930s purchase of the Russian Imperial Collection, consisting of 2,600 volumes from the library of the Romanov family on a variety of topics. Collections of Hebraica and Chinese and Japanese works were also acquired.[6] Congress even took the initiative to acquire materials for the Library in one occasion, when in 1929 Congressman Ross Collins of Mississippi successfully proposed the $1.5 million purchase of Otto Vollbehr's collection of incunabula, including one of three remaining perfect vellum copies of the Gutenberg Bible.[6]

In 1914, Putnam established the Legislative Reference Service as a separative administrative unit of the Library. Based in the Progressive era's philosophy of science as a problem-solver, and modeled after successful research branches of state legislatures, the LRS would provide informed answers to Congressional research inquiries on almost any topic.[6] In 1965 Congress passed an act allowing the Library of Congress to establish a trust fund board to accept donations and endowments, giving the Library a role as a patron of the arts. The Library received the donations and endowments of prominent individuals such as John D. Rockefeller, James B. Wilbur and Archer M. Huntington. Gertrude Clarke Whittall donated five Stradivarius violins to the Library and Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge's donations paid for a concert hall within the Library of Congress building and the establishment of an honorarium for the Music Division. A number of chairs and consultantships were established from the donations, the most well-known of which is the Poet Laureate Consultant.[6]

The Library's expansion eventually filled the Library's Main Building, despite shelving expansions in 1910 and 1927, forcing the Library to expand into a new structure. Congress acquired nearby land in 1928 and approved construction of the Annex Building (later the John Adams Building) in 1930. Although delayed during the Depression years, it was completed in 1938 and opened to the public in 1939.[6]

Modern history (1939–present)

When Putnam retired in 1939, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Archibald MacLeish as his successor. Occupying the post from 1939 to 1944 during the height of World War II, MacLeish became the most visible Librarian of Congress in the Library's history. MacLeish encouraged librarians to oppose totalitarianism on behalf of democracy; dedicated the South Reading Room of the Adams Building to Thomas Jefferson, commissioning artist Ezra Winter to paint four themed murals for the room; and established a "democracy alcove" in the Main Reading Room of the Jefferson Building for important documents such as the Declaration, Constitution and Federalist Papers.[6] Even the Library of Congress assisted during the war effort, ranging from the storage of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution in Fort Knox for safekeeping to researching weather data on the Himalayas for Air Force pilots.[6] MacLeish resigned in 1944 to become Assistant Secretary of State, and President Harry Truman appointed Luther H. Evans as Librarian of Congress. Evans, who served until 1953, expanded the Library's acquisitions, cataloging and bibliographic services as much as the fiscal-minded Congress would allow, but his primary achievement was the creation of Library of Congress Missions around the world. Missions played a variety of roles in the postwar world: the mission in San Francisco assisted participants in the meeting that established the United Nations, the mission in Europe acquired European publications for the Library of Congress and other American libraries, and the mission in Japan aided in the creation of the National Diet Library.[6]

Evans' successor L. Quincy Mumford took over in 1953. Mumford's tenure, lasting until 1974, saw the initiation of the construction of the James Madison Memorial Building, the third Library of Congress building. Mumford directed the Library during a period of increased educational spending, the windfall of which allowed the Library to devote energies towards establishing new acquisition centers abroad, including in Cairo and New Delhi. In 1967 the Library began experimenting with book preservation techniques through a Preservation Office, which grew to become the largest library research and conservation effort in the United States.[6] Mumford's administration also saw the last major public debate about the Library of Congress' role as both a legislative library and a national library. A 1962 memorandum by Douglas Bryant of the Harvard University Library, compiled at the request of Joint Library Committee chairman Claiborne Pell, proposed a number of institutional reforms, including expansion of national activities and services and various organizational changes, all of which would shift the Library more towards its national role over its legislative role. Bryant even suggested possibly changing the name of the Library of Congress, which was rebuked by Mumford as "unspeakable violence to tradition".[6] Debate continued within the library community until the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970 shifted the Library back towards its legislative roles, placing greater focus on research for Congress and congressional committees and renaming the Legislative Reference Service to the Congressional Research Service.[6]

After Mumford retired in 1974, Gerald Ford appointed Daniel J. Boorstin as Librarian. Boorstin's first challenge was the move to the new Madison Building, which took place between 1980 and 1982. The move released pressures on staff and shelf space, allowing Boorstin to focus on other areas of Library administration such as acquisitions and collections. Taking advantage of steady budgetary growth, from $116 million in 1975 to over $250 million by 1987, Boorstin actively participated in enhancing ties with scholars, authors, publishers, cultural leaders, and the business community. His active and prolific role changed the post of Librarian of Congress so that by the time he retired in 1987, the New York Times called it "perhaps the leading intellectual public position in the nation."[6] Ronald Reagan appointed James H. Billington as the thirteenth Librarian of Congress in 1987, a post he holds as of 2012. Billington took advantage of new technological advancements and the Internet to link the Library to educational institutions around the country in 1991. The end of the Cold War also enabled the Library to develop relationships with newly open Eastern European nations, helping them to establish parliamentary libraries of their own.[6]

In the mid-1990s, under Billington's leadership, the Library of Congress began to pursue the development of what it called a "National Digital Library," part of an overall strategic direction that has been somewhat controversial within the library profession.[10] In late November 2005, the Library announced intentions to launch the World Digital Library, digitally preserving books and other objects from all world cultures. In April 2010, it announced plans to archive all public communication on Twitter, including all communication since Twitter's launch in March 2006.[11] The Twitter archive is another example of the Library's commitment to collecting first-person accounts of history.[12]

Holdings

The collections of the Library of Congress include more than 32 million cataloged books and other print materials in 470 languages; more than 61 million manuscripts; the largest rare book collection in North America, including the rough draft of the Declaration of Independence, a Gutenberg Bible (one of only three perfect vellum copies known to exist);[13] over 1 million US government publications; 1 million issues of world newspapers spanning the past three centuries; 33,000 bound newspaper volumes; 500,000 microfilm reels; over 6,000 titles in all, totaling more than 120,000 issues comic book[14] titles; films; 5.3 million maps; 6 million works of sheet music; 3 million sound recordings; more than 14.7 million prints and photographic images including fine and popular art pieces and architectural drawings;[15] the Betts Stradivarius; and the Cassavetti Stradivarius.

The Library developed a system of book classification called Library of Congress Classification (LCC), which is used by most US research and university libraries.

The Library serves as a legal repository for copyright protection and copyright registration, and as the base for the United States Copyright Office. Regardless of whether they register their copyright, all publishers are required to submit two complete copies of their published works to the Library—this requirement is known as mandatory deposit.[16] Nearly 22,000 new items published in the U.S. arrive every business day at the Library. Contrary to popular belief, however, the Library does not retain all of these works in its permanent collection, although it does add an average of 10,000 items per day. Rejected items are used in trades with other libraries around the world, distributed to federal agencies, or donated to schools, communities, and other organizations within the United States.[17] As is true of many similar libraries, the Library of Congress retains copies of every publication in the English language that is deemed significant.

The Library of Congress states that its collection fills about 838 miles (1,349 km) of bookshelves, while the British Library reports about 388 miles (624 km) of shelves.[18][19] The Library of Congress holds more than 155.3 million items with more than 35 million books and other print materials, against approximately 150 million items with 25 million books for the British Library.[18][19] A 2000 study by information scientists Peter Lyman and Hal Varian suggested that the amount of uncompressed textual data represented by the 26 million books then in the collection was 10 terabytes.[20]

The Library makes millions of digital objects, comprising tens of petabytes, available at its American Memory site. American Memory is a source for public domain image resources, as well as audio, video, and archived Web content. Nearly all of the lists of holdings, the catalogs of the library, can be consulted directly on its web site. Librarians all over the world consult these catalogs, through the Web or through other media better suited to their needs, when they need to catalog for their collection a book published in the United States. They use the Library of Congress Control Number to make sure of the exact identity of the book.

The Library of Congress also provides an online archive of the proceedings of the U.S. Congress at THOMAS, including bill text, Congressional Record text, bill summary and status, the Congressional Record Index, and the United States Constitution.

The Library also administers the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped, an audio book and braille library program provided to more than 766,000 Americans.

Buildings of the Library

The Library of Congress is physically housed in three buildings on Capitol Hill and a conservation center in rural Virginia. The Library's Capitol Hill buildings are all connected by underground passageways, so that a library user need pass through security only once in a single visit. The library also has off-site storage facilities for less commonly requested materials.

Thomas Jefferson Building

The Thomas Jefferson Building is located between Independence Avenue and East Capitol Street on First Street SE. It first opened in 1897 as the main building of the Library and is the oldest of the three buildings. Known originally as the Library of Congress Building or Main Building, it took its present name on June 13, 1980.

John Adams Building

The John Adams Building is located between Independence Avenue and East Capitol Street on 2nd Street SE, the block adjacent to the Jefferson Building. The building was originally built simply as an annex to the Jefferson Building. It opened its doors to the public on January 3, 1939.

James Madison Memorial Building

The James Madison Memorial Building is located between First and Second Streets on Independence Avenue SE. The building was constructed from 1971 to 1976, and serves as the official memorial to President James Madison.

The Madison Building is also home to the Mary Pickford Theater, the "motion picture and television reading room" of the Library of Congress. The theater hosts regular free screenings of classic and contemporary movies and television shows.

Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation

The Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation is the Library of Congress's newest building, opened in 2007 and located in Culpeper, Virginia.[21] It was constructed out of a former Federal Reserve storage center and Cold War bunker. The campus is designed to act as a single site to store all of the library's movie, television, and sound collections. It is named to honor David Woodley Packard, whose Packard Humanities Institute oversaw design and construction of the facility. The centerpiece of the complex is a reproduction Art Deco movie theater that presents free movie screenings to the public on a semi-weekly basis.[22]

Using the Library

The library is open to the general public for academic research and tourism. Only those who are issued a Reader Identification Card may enter the reading rooms and access the collection. The Reader Identification Card is available in the Madison building to persons who are at least 16 years of age upon presentation of a government issued picture identification (e.g. driver's license, state ID card or passport).[23] However, only members of Congress, Supreme Court Justices, their staff, Library of Congress staff and certain other government officials may actually remove items from the library buildings. Members of the general public with Reader Identification Cards must use items from the library collection inside the reading rooms only; they are not allowed to remove library items from the reading rooms or the library buildings.[citation needed]

Since 1902, libraries in the United States have been able to request books and other items through interlibrary loan from the Library of Congress if these items are not readily available elsewhere. Through this, the Library of Congress has served as a "library of last resort", according to former Librarian of Congress Herbert Putnam.[9] The Library of Congress lends books to other libraries with the stipulation that they be used only inside the borrowing library.[24]

The Library of Congress is sometimes used as an unusual unit of measurement to represent an impressively large quantity of data when discussing digital storage or networking technologies. [citation needed]

Standards

In addition to its library services, the Library of Congress is also actively involved in various standard activities in areas related to bibliographical and search and retrieve standards. Areas of work include MARC standards, METS, Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS), Z39.50 and Search/Retrieve Web Service (SRW), and Search/Retrieve via URL (SRU). [citation needed]

Annual events

- Archives Fair

- Fellows in American Letters of the Library of Congress

- Davidson Fellows Reception

- Founder's Day Celebration

- Gershwin Prize for Popular Song

- Judith P. Austin Memorial Lecture

- The National Book Festival

See also

- Anderson, Gillian B. (1989), "Putting the Experience of the World at the Nation's Command: Music at the Library of Congress, 1800-1917", Journal of the American Musciological Society 42 (1): [108]-149

- Documents Expediting Project

- Federal Research Division

- Feleky Collection

- History of Public Library Advocacy

- Law Library of Congress

- Library of Congress Classification

- Library of Congress Country Studies

- Library of Congress Digital Library project

- Library of Congress Living Legend

- Library of Congress Subject Headings

- List of librarians

- List of national libraries

- List of unusual units of measurement#Data volume

- MARC standards

- Minerva Initiative

- National Archives and Records Administration

- National Digital Information Infrastructure and Preservation Program

- National Film Registry

- National Recording Registry

- Public Library Advocacy

- United States National Agricultural Library (NAL)

- United States National Library of Education

- United States National Library of Medicine (NLM)

- United States Senate Library

- Veterans History Project of the Library of Congress American Folklife Center

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "2010 At A Glance". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

- ↑ "The Packard Campus". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ↑ http://www.webcitation.org/66R0Tpvsg

- ↑ purplemotes.net- Jefferson got $23,940

- ↑ loc.gov

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 6.17 6.18 6.19 6.20 6.21 6.22 6.23 6.24 6.25 6.26 6.27 "Jefferson's Legacy: A Brief History of the Library of Congress". Library of Congress. March 6, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2008.

- ↑ "Thomas Jefferson's personal library at Library Thing, based on scholarship". Librarything.com. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

- ↑ Library Thing Profile Page for Thomas Jefferson's library, summarizing contents and indicating sources

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Interlibrary Loan (Collections Access, Management and Loan Division, Library of Congress)". Library of Congress website. October 25, 2007. Retrieved December 4, 2007.

- ↑ Collins, Samuel (2009). Library of Walls: The Library of Congress and the Contradictions of Information Society. Litwin Books. ISBN 978-0-9802004-2-3.

- ↑ Peter Grier. "Twitter hits Library of Congress: Would Founding Fathers tweet?". CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

- ↑ "Twitter Archive to Library of Congress - News Releases (Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

- ↑ See Gutenberg's Bibles— Where to Find Them; Octavo Digital Rare Books; Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Comic Book Collection". The Library of Congress. April 7, 2006. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Librarian of Congress, Library of Congress, 2009

- ↑ "Mandatory Deposit". Copyright.gov. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ↑ "Fascinating Facts". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 8, 2006.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Fascinating Facts – About the Library". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Facts and figures". British Library. Retrieved June 30, 2011.

- ↑ Peter Lyman, Hal R. Varian (2000-10-18). "How Much Information?". Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ Packard Campus for Audio-Visual Conservation

- ↑ "Library of Congress events listing". Loc.gov. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

- ↑ "Library of Congress". Loc.gov. 2009-04-15. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

- ↑ "Subpage Title (Interlibrary Loan, Library of Congress)". Loc.gov. 2010-07-14. Retrieved 2012-11-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Library of Congress. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1905 New International Encyclopedia article about Library of Congress. |

- The Library of Congress website

- American Memory

- History of the Library of Congress

- Library of Congress National Book Festival authors roster

- Memory and Imagination: New Pathways to the Library of Congress Documentary

- poets.org (About the 2012 National Book Festival from The Academy of American Poets)

- Search the Library of Congress catalog

- thomas.loc.gov, legislative information

- Library Of Congress Meeting Notices and Rule Changes from The Federal Register RSS Feed

- Library of Congress photos on Flickr

- Outdoor sculpture at the Library of Congress

- Standards, The Library of Congress

- Works by the Library of Congress at Project Gutenberg

- Library of Congress at FamilySearch Research Wiki for genealogists

-

"Congress, Library of". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

"Congress, Library of". Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

| |||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|