Liénard–Wiechert potential

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

|

Liénard–Wiechert potentials describe the classical electromagnetic effect of a moving electric point charge in terms of a vector potential and a scalar potential in the Lorenz gauge. Built directly from Maxwell's equations, these potentials describe the complete, relativistically correct, time-varying electromagnetic field for a point charge in arbitrary motion, but are not corrected for quantum-mechanical effects. Electromagnetic radiation in the form of waves can be obtained from these potentials.

These expressions were developed in part by Alfred-Marie Liénard in 1898 and independently by Emil Wiechert in 1900[1] and continued into the early 1900s.

Implications

The study of classical electrodynamics was instrumental in Einstein's development of the theory of relativity. Analysis of the motion and propagation of electromagnetic waves led to the special relativity description of space and time. The Liénard–Wiechert formulation is an important launchpad into more complex analysis of relativistic moving particles.

The Liénard–Wiechert description is accurate for a large, independent moving particle, but breaks down at the quantum level.

Quantum mechanics sets important constraints on the ability of a particle to emit radiation. The classical formulation, as laboriously described by these equations, expressly violates experimentally observed phenomena. For example, an electron around an atom does not emit radiation in the pattern predicted by these classical equations. Instead, it is governed by quantized principles regarding its energy state. In the later decades of the twentieth century, quantum electrodynamics helped bring together the radiative behavior with the quantum constraints.

Universal Speed Limit

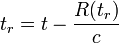

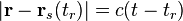

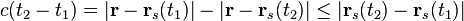

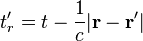

The force on a particle at a given location r and time t depends in a complicated way on the position of the source particles at an earlier time tr due to the finite speed, c, at which electromagnetic information travels. A particle on Earth 'sees' a charged particle accelerate on the Moon as this acceleration happened 1.5 seconds ago, and a charged particle's acceleration on the Sun as happened 500 seconds ago. This earlier time in which an event happens such that a particle at location r 'sees' this event at a later time t is called the retarded time, tr. The retarded time varies with position; for example the retarded time at the Moon is 1.5 seconds before the current time and the retarded time on the Sun is 500 s before the current time. The retarded time can be calculated as:

where  is the distance of the particle from the source at the retarded time. Only electromagnetic wave effects depend fully on the retarded time.

is the distance of the particle from the source at the retarded time. Only electromagnetic wave effects depend fully on the retarded time.

A novel feature in the Liénard–Wiechert potential is seen in the breakup of its terms into two types of field terms (see below), only one of which depends fully on the retarded time. The first of these is the static electric (or magnetic) field term that depends only on the distance to the moving charge, and does not depend on the retarded time at all, if the velocity of the source is constant. The other term is dynamic, in that it requires that the moving charge be accelerating with a component perpendicular to the line connecting the charge and the observer and does not appear unless the source changes velocity. This second term is connected with electromagnetic radiation.

The first term describes near field effects from the charge, and its direction in space is updated with a term that corrects for any constant-velocity motion of the charge on its distant static field, so that the distant static field appears at distance from the charge, with no aberration of light or light-time correction. This term, which corrects for time-retardation delays in the direction of the static field, is required by Lorentz invariance. A charge moving with a constant velocity must appear to a distant observer in exactly the same way as a static charge appears to a moving observer, and in the latter case, the direction of the static field must change instantaneously, with no time-delay. Thus, static fields (the first term) point exactly at the true instantaneous (non-retarded) position of the charged object if its velocity has not changed over the retarded time delay. This is true over any distance separating objects.

The second term, however, which contains information about the acceleration and other unique behavior of the charge that cannot be removed by changing the Lorentz frame (inertial reference frame of the observer), is fully dependent for direction on the time-retarded position of the source. Thus, electromagnetic radiation (described by the second term) always appears to come from the direction to the position of the emitting charge at the retarded time. Only this second term describes information transfer about the behavior of the charge, which transfer occurs (radiates from the charge) at the speed of light. At "far" distances (longer than several wavelengths of radiation), the 1/R dependence of this term makes electromagnetic field effects (the value of this field term) more powerful than "static" field effects, which are described by the 1/R2 potential of the first (static) term and thus decay more rapidly with distance from the charge.

Existence and uniqueness of the retarded time

Existence

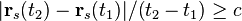

The retarded time is not guaranteed to exist in general. For example, if, in a given frame of reference, an electron has just been created, then at this very moment another electron does not yet feel its electromagnetic force at all. However, under certain conditions, there always exists a retarded time. For example, if the source charge has existed for an unlimited amount of time, during which it has always travelled at a speed not exceeding  , then there exists a valid retarded time

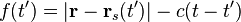

, then there exists a valid retarded time  . To see this, consider the function

. To see this, consider the function  . At the present time,

. At the present time,  , we have

, we have  . The derivative

. The derivative  is given by

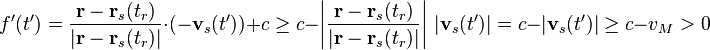

is given by

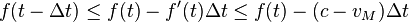

By the mean value theorem,  . By making

. By making  sufficiently large, we can force this to be negative, i.e., at some point in the past,

sufficiently large, we can force this to be negative, i.e., at some point in the past,  . By the intermediate value theorem, there exists an intermediate

. By the intermediate value theorem, there exists an intermediate  with

with  , the defining equation of the retarded time. Intuitively, as the source charge moves back in time, the cross section of its light cone at present time expands faster than it can recede, so eventually it must reach the point

, the defining equation of the retarded time. Intuitively, as the source charge moves back in time, the cross section of its light cone at present time expands faster than it can recede, so eventually it must reach the point  . Note that this is not necessarily true if the source charge's speed is allowed to be arbitrarily close to

. Note that this is not necessarily true if the source charge's speed is allowed to be arbitrarily close to  , i.e., if for any given speed

, i.e., if for any given speed  there was some time in the past when the charge was moving at this speed. In this case the cross section of the light cone at present time approaches the point

there was some time in the past when the charge was moving at this speed. In this case the cross section of the light cone at present time approaches the point  as we travel back in time but does not necessarily ever reach it.

as we travel back in time but does not necessarily ever reach it.

Uniqueness

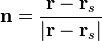

For a given point  and trajectory of the point source

and trajectory of the point source  , there is at most one value of the retarded time

, there is at most one value of the retarded time  , i.e., one value

, i.e., one value  such that

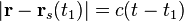

such that  . To see this, suppose there are two retarded times

. To see this, suppose there are two retarded times  and

and  , with

, with  . Then,

. Then,  and

and  . Subtracting gives

. Subtracting gives  by the triangle inequality. Unless

by the triangle inequality. Unless  , this then implies that the average velocity of the charge between

, this then implies that the average velocity of the charge between  and

and  is

is  , which is impossible. The intuitive interpretation is that we can only ever "see" the point source at one location/time at once unless it travels at least at the speed of light to another location. As the source moves forward in time, the cross section of its light cone at present time contracts faster than the source can approach, so it can never intersect the point

, which is impossible. The intuitive interpretation is that we can only ever "see" the point source at one location/time at once unless it travels at least at the speed of light to another location. As the source moves forward in time, the cross section of its light cone at present time contracts faster than the source can approach, so it can never intersect the point  again.

again.

We conclude that, under certain conditions, the retarded time exists and is unique.

Equations

Definition of Liénard-Wiechert potentials

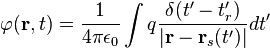

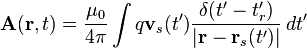

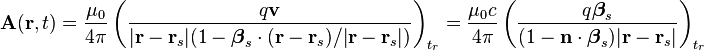

The Liénard–Wiechert potentials  (scalar potential field) and

(scalar potential field) and  (vector potential field) are for a source point charge

(vector potential field) are for a source point charge  at position

at position  traveling with velocity

traveling with velocity  :

:

and

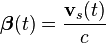

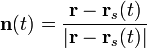

where  and

and  .

.

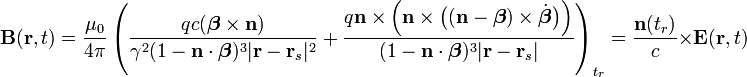

Corresponding values of electric and magnetic fields

We can calculate the electric and magnetic fields directly from the potentials using the definitions:

and

and

The calculation is nontrivial and requires a number of steps. The electric and magnetic fields are (in non-covariant form):

and

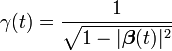

where  ,

,  and

and  (the Lorentz factor).

(the Lorentz factor).

Note that the  part of the first term updates the direction of the field toward the instantantaneous position of the charge, if it continues to move with constant velocity

part of the first term updates the direction of the field toward the instantantaneous position of the charge, if it continues to move with constant velocity  . This term is connected with the "static" part of the electromagnetic field of the charge.

. This term is connected with the "static" part of the electromagnetic field of the charge.

The second term, which is connected with electromagnetic radiation by the moving charge, requires charge acceleration  and if this is zero, the value of this term is zero, and the charge does not radiate (emit electromagnetic radiation). This term requires additionally that a component of the charge acceleration be in a direction transverse to the line which connects the charge

and if this is zero, the value of this term is zero, and the charge does not radiate (emit electromagnetic radiation). This term requires additionally that a component of the charge acceleration be in a direction transverse to the line which connects the charge  and the observer of the field

and the observer of the field  . The direction of the field associated with this radiative term is toward the fully time-retarded position of the charge (i.e. where the charge was when it was accelerated).

. The direction of the field associated with this radiative term is toward the fully time-retarded position of the charge (i.e. where the charge was when it was accelerated).

Derivation

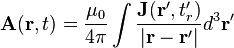

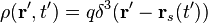

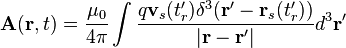

In the case that there are no boundaries surrounding the sources, the retarded solutions for the scalar and vector potentials (SI units) of the nonhomogeneous wave equations with sources given by the charge and current densities  and

and  are in the Lorenz gauge (see Nonhomogeneous electromagnetic wave equation)

are in the Lorenz gauge (see Nonhomogeneous electromagnetic wave equation)

and

where  is the retarded time.

is the retarded time.

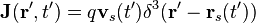

For a moving point charge whose trajectory is given as a function of time by  , the charge and current densities are as follows:

, the charge and current densities are as follows:

where  is the three-dimensional Dirac delta function and

is the three-dimensional Dirac delta function and  is the velocity of the point charge.

is the velocity of the point charge.

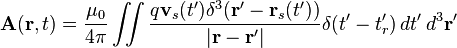

Substituting into the expressions for the potential gives

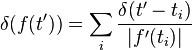

These integrals are difficult to evaluate in their present form, so we will rewrite them by replacing  with

with  and integrating over the delta distribution

and integrating over the delta distribution  :

:

We exchange the order of integration:

The delta function picks out  which allows us to perform the inner integration with ease. Note that

which allows us to perform the inner integration with ease. Note that  is a function of

is a function of  , so this integration also fixes

, so this integration also fixes  .

.

The retarded time  is a function of the field point

is a function of the field point  and the source point

and the source point  , and hence depends on

, and hence depends on  . To evaluate this integral, therefore, we need the identity

. To evaluate this integral, therefore, we need the identity

where each  is a zero of

is a zero of  . Because there is only one retarded time

. Because there is only one retarded time  for any given space-time coordinates

for any given space-time coordinates  and source trajectory

and source trajectory  , this reduces to:

, this reduces to:

where  , and

, and  and

and  are evaluated at the retarded time, and we have used the identity

are evaluated at the retarded time, and we have used the identity  . Finally, the delta function picks out

. Finally, the delta function picks out  , and

, and

which are the Liénard-Wiechert potentials.

See also

- Maxwell's equations which govern classical electromagnetism

- Classical electromagnetism for the larger theory surrounding this analysis

- Relativistic electromagnetism

- Special relativity, which was a direct consequence of these analyses

- Rydberg formula for quantum description of the EM radiation due to atomic orbital electrons

- Jefimenko's equations

- Larmor formula

- Abraham-Lorentz force

- Inhomogeneous electromagnetic wave equation

- Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory also known as the Wheeler-Feynman time-symmetric theory

References

- Griffiths, David. Introduction to Electrodynamics. Prentice Hall, 1999. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.