Leicester Abbey

Low walls laid out on the general plan of Leicester Abbey, which was established during excavations in the 1920s and 1930s. | |

Location within Leicestershire

| |

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The Abbey of St Mary de Pratis, Leicester |

| Order | Augustinian Canons |

| Established | 1143 |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Dedicated to |

The Assumption of the Virgin Mary; and St Mary de Pratis: St. Mary of the Meadows |

| Diocese | Diocese of Lincoln |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Robert le Bossu, Earl of Leicester |

| Important associated figures |

|

| Site | |

| Location | Leicester |

| Coordinates | 52°38′56″N 1°08′13″W / 52.648948°N 1.13687°WCoordinates: 52°38′56″N 1°08′13″W / 52.648948°N 1.13687°W |

| Grid reference | SK5849206040 |

| Visible remains | Low walls indicating the plan of the abbey and the ruins of Cavendish House. |

The Abbey of Saint Mary de Pratis, more commonly known as Leicester Abbey, was an Augustinian religious house in the city of Leicester, in the English Midlands. The abbey was founded in the 12th century by the 2nd Earl of Leicester, and grew to become the wealthiest religious establishment within Leicestershire. Through patronage and donations the abbey gained the advowsons of countless churches throughout England, and acquired a considerable amount of land, and several manorial lordships. Leicester Abbey also maintained a cell (a small dependent daughter house) at Cockerham Priory, in Lancashire. The Abbey's prosperity was boosted though the passage of special privileges by both the English Kings and the Pope. These included an exemption from sending representatives to parliament and from paying tithe on certain land and livestock. Despite its privileges and sizeable landed estates, from the late 14th century the abbey began to suffer financially and was forced to lease out its estates. The worsening financial situation was exacerbated throughout the 15th century and early 16th century by a series of incompetent, corrupt and extravagant abbots. By 1535 the abbey's considerable income was exceeded by even more considerable debts.

The abbey provided a home to an average of 30 to 40 canons, sometimes known as Black Canons, because of their dress (a white habit and black cloak). One of these canons, Henry Knighton, is notable for his Chronicle, which was written during his time at the abbey in the 14th century. In 1530 Cardinal Thomas Wolsey died at the abbey, whilst travelling south to face trial for treason. A few years later, in 1538, the abbey was dissolved, and was quickly demolished, with the building materials reused in various structures across Leicester, including a mansion which was built on the site. The house passed through several aristocratic families, and became known as Cavendish House after it was acquired by the 1st Earl of Devonshire, in 1613. The house was eventually looted and destroyed by fire in 1645, following the capture of Leicester during the English Civil War.

Part of the former abbey precinct was donated to Leicester Town Council (the predecessor of the modern City Council) by the 8th Earl of Dysart. In 1882 it was opened by The Prince of Wales and became known as Abbey Park. The remaining 32 acres (13 ha), which included the abbey's site and the ruins of Cavendish House, were donated to the council by the 9th Earl of Dysart in 1925 and, following archaeological excavations, opened to the public in the 1930s. Following its demolition, the exact location of the abbey was lost; It was only rediscovered during excavations in the 1920s/30s, when the layout was plotted using low stone walls. The abbey has been extensively excavated and was previously used for training archaeology students at the University of Leicester. Leicester Abbey is now protected as a scheduled monument and is Grade I Listed.

History

Foundation

Leicester Abbey was founded during a wave of monastic enthusiasm that swept through western Christendom in the 11th and 12th centuries.[2] This wave was responsible for the foundation of the majority of England's monasteries, and very few were founded after the 13th century. These monasteries were often founded by a wealthy aristocratic benefactor who endowed and patronised the establishments in return for prayers for their soul, and often, the right to be buried within the monastic church.[2] Leicester Abbey was founded in the Augustinian tradition. The monks at the abbey were known as canons, and followed the monastic rules set down by Saint Augustine of Hippo. Sometimes known as Black Canons, because of their dress (a white habit and black cloak), Augustinian Canons lived a clerical life engaged in public ministry; this is distinct to other forms of monasticism in which monks were cloistered from the outside world, and lived an isolated, contemplative life.[3]

Leicester Abbey was founded in 1143 by Robert le Bossu, 2nd Earl of Leicester, and was dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary.[4] It was not the first abbey Robert had established, having founded Garendon Abbey, also in Leicestershire, in 1133.[5] Robert's father, Robert de Beaumont, 1st Earl of Leicester, had previously founded a college of secular canons in Leicester, known as The College of St Mary de Castro. The new abbey assumed control of the college and its possessions, which included all of the churches in Leicester. Robert added to this with the gift of numerous churches in Leicestershire, Berkshire and Northamptonshire. The abbey also gained the manor of Asfordby from its merger with the college, and the manor of Knighton from its founder.[4]

The earls of Leicester continued to patronise the abbey: Petronilla de Grandmesnil, wife of the founder's son, Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester, financed the construction of the abbey's Great Choir; whilst her husband donated 24 virgates (720 acres) of land at Anstey.[4]

In 1148, Pope Eugene III granted the abbey an exemption on paying tithe for their newly acquired land and livestock. This was granted on the condition that there was to be no impropriety or violence when electing an abbot, and that those who donated money to the abbey could be buried within it, regardless of whether they had been excommunicated.[6]

14th century

Though the abbey was a religious house, it was attacked in 1326 by the Earl of Lancaster's soldiers, who seized property belonging to Hugh le Despenser, 1st Earl of Winchester, which was being kept there.[4]

Under the Abbotship of William Clowne (tenure: 1345–1378) the abbey prospered, increasing their lands and endowments with acquisitions such as the manors of Ingarsby and Kirkby Mallory. Clowne is described as having "friendly relations" with King Edward III, and used this to gain further privileges for the abbey, including being exempted from having to send representatives to Parliament. However, by the late 14th century, the abbey had entered a difficult period, and its income began to fall.[4]

It was during this period that the abbey was home to canon Henry of Knighton, who wrote Knighton's Chronicon.[7] The chronicle includes both Knighton's contemporary experiences, between 1377 and 1395, and a historical section recording events between 1066 and 1366.[8] Knighton chronicles the impact of John Wycliffe, the rise of the Lollards, and gives an unusually favourable account of John of Gaunt.[7] Knighton's chronicle is valued by historians for his contemporary account of the Black Death in Leicester, which has been compared with Giovanni Boccaccio's Decameron, which chronicles the plague in Florence.[9] His in depth account records the effects of the Black Death on Leicester. This includes the impact on the prices of food, grain, wine and cattle, and on changes in wages and the labour market. The chronicle also includes detailed death tolls for all of Leicester's parishes, revealing that one-third of the population of Leicester were killed by the disease.[9][10] Following the deaths of canons within the abbey, Knighton theorises that it was punishment because of "the ordination of candidates ill-prepared and but little suited for the sacred ministry".[10] The chronicle was not published until 1652.[7]

15th century

In the 15th century the abbey began to lease out its land (most probably as a solution to their falling income). By 1477 only the demesne lands in Leicester, Stoughton and Ingarsby remained un-leased, and were directly farmed by the abbey.[4]

Philip Repyngdon served as Abbot of Leicester Abbey from 1393 to 1405, when he resigned to become "Chaplain and Confessor" to King Henry IV, and subsequently served as Bishop of Lincoln and as a Cardinal. Repyngdon's successor, Richard of Rothely, was granted a Royal Licence permitting him to ask the Pope for to remove the abbey from the Bishop of Lincoln's jurisdiction, as the abbot feared Repyngdon would interfere with his former abbey, which lay within that Diocese. It is unclear if the Pope ever agreed to this petition, as Repyngdon also petitioned the Pope; receiving a declaration confirming that Leicester Abbey was "fully subject to him and his successors".[4]

Under the tenure of Abbot William Sadyngton (1420—42) the abbey's fortunes fell further. A visit by William Alnwick, Bishop of Lincoln, in 1440, revealed the number of canons had fallen from 30 to 40 to just 14 and that the number of boys in the almonry had fallen from 25 to 6. Sadyngton was accused of various unsavory practices: of accepting unsuitable boys into the almonry in return for money, of "pocketing various minor revenues", of "keeping the offices of treasurer and cellarer in his own hands" and of not disclosing the abbey's accounts to his canons. Sadyngton was also known to keep servants and was even accused of practising magic, including divination.[4]

Despite Abbot Sadyngton's apparent financial corruption, the abbey appeared to be financially stable: the abbey's monastic buildings had recently been extensively rebuilt and the abbey had a substantial annual income of £1180. Perhaps because of the large income the Abbot was sustaining, Bishop Alnwick appears to have not taken strong measures against the Abbot's indiscretions. He ordered that the number of canons should be increased to 30 and the number of boys in the almonry increased to 16. The Bishop also ordered proper accounts to be kept and forbade the abbot from granting favours without the permission of both the Bishop and the Canons.[4]

16th century

In 1518 William Atwater, Bishop of Lincoln, visited to inspect the abbey. The Abbot, Richard Pescall, was, like Sadyngton, accused of financial impropriety, but also was thought to be too old to perform his duties. Pescall's extravagances included an "excessive number of hounds", which were known to roam freely "fouling church, chapter house and cloister"; whilst the Bishop complained the boys in the almonry were being improperly educated.[4][11]

A followup visit, in 1521, by Bishop Atwater's successor, John Longland, showed that things had not improved. Abbot Pescall rarely attended church services and, when he did, he would often bring his jester who "disturbed the services with his buffoonery". The Abbot's bad example had affected the canon's behaviour, who ate and drank at improper times, failed to attend services (an average of 11 of the 25 canons attended) and roamed freely outside the abbey: visiting the town's alehouses and frequently going hunting.[4][11] Two canons were also accused of "incontinence". This visit revealed the abbey was severely in debt, leading the Bishop to appoint two administrators to oversee the abbey's finances.[4]

The Chancellor of Lincoln Diocese visited the abbey in 1528 and found things had not improved. The abbot was still not attending services and was eating at unusual times and in unusual places, away from the other canons. The Chancellor also complained about the Abbot's "excessive number" of servants. The 24 canons were also still in the habit of leaving the abbey without proper reason.[4]

Bishop Longland saw no alternative but to remove Abbot Pescall, but the task was not simple as Pescall tried to secure his position by sending gifts and bribes to Thomas Cromwell, leading Bishop Longland to resort to "harassing" the Abbot by constantly interfering with affairs at the abbey.[4][11] Abbot Pescall finally resigned 5 years later (10 years after his "failures" were first noticed) and was granted a pension of £100 a year. Pescall's retirement was far from quiet, however. Pescall frequently wrote to Thomas Cromwell complaining about affairs at the abbey, even bemoaning the fact that £13 of his undeservedly generous pension of £100 a year was being taken in tax, and asking that the tax be paid by the abbey.[11]

It was during Abbot Pescall's tenure, in 1530, that Cardinal Thomas Wolsey visited the abbey.[4] Wolsey was an influential minister in the government of King Henry VIII. He fell from favour after failing to secure papal permission for Henry to divorce his wife Katherine of Aragon, and on 4 November 1530 was arrested for treason. While en route from Yorkshire to London, where Wolsey would be held prisoner, he fell ill. The journey took Wolsey through Leicester, and he arrived at the abbey on 26 November, declaring: "Father abbott, I ame come hether to leave my bones among you".[12] Wolsey died on 30 November and the public were allowed to view his remains before he was interred within the abbey's church.[12]

By the time Pescall was removed, the abbey's financial position was poor: Despite being the richest monastery in Leicestershire (with an income of £951 in 1534), it owed a total of £1,000 to debtors. John Bourchier, who would be the last abbot of the house, took control in 1534 and by 1538 had reduced the debt to £411.[4] Abbots were usually elected from among the canons of the abbey: Bourchier represented a departure from tradition. Bourchier[nb 1] most probably gained the position of abbot on the instigation of the influential Robert Fuller, Abbot of Waltham Abbey, and on the promise of a bribe for Henry VIII's chief adviser, Thomas Cromwell. Exact details are unknown, but letters seem to suggest Cromwell was promised his nephew Richard Williams (Cromwell) would be given £100 and the lease of the abbey's grange at Ingarsby; the promise was only honoured in April 1536, as Bourchier faced opposition from the canons of the abbey. Historians have suggested that in choices such as Bourchier, Cromwell may have been selecting abbots he felt would be more "pliable" his future changes to the church (i.e. the future Dissolution of the Monasteries, of which Cromwell was the architect).[11]

In 1527 King Henry VIII asked Pope Clement VII to annul his marriage to Katherine of Aragon, but the pope refused. This started a series of events known as English Reformation in which Henry broke away from the authority of the pope.[13] In lieu of the pope, Henry assumed authority over the church: all priests and religious figures, including monks, were required to swear support to the royal supremacy over the church. Abbot Bourchier and the 25 canons at Leicester Abbey acknowledged the king's royal supremacy on 11 August 1534, thereby saving the abbey from immediate dissolution.[4]

Thomas Cromwell, Henry's Chief Minister, had long since had his eyes on the wealth of English monasteries; at the time they owned approximately a quarter of all the realm's landed wealth. Starting in 1534, Cromwell had every monasteries inspected, with the establishment's wealth and endowments recorded, along with frequent reports of impropriety, vice and excess. These reports were compiled into volumes known as the Valor Ecclesiasticus. Leicester abbey was inspected by Richard Layton, in 1535, who complimented Abbot Bourchier as an honest man, but who tried to bring charges of "adultery and unnatural vice" against the abbey's canons. Abbot Bourchier sought to gain Thomas Cromwell's favour to protect his canons and abbey; in 1536 sending him £100 and gifts of sheep and oxen. This was ultimately fruitless: Cromwell had convinced King Henry of the immoral behaviour within England's monasteries and thus between 1536 and 1541 they were all suppressed and dissolved: their land, property and wealth transferred to the king. The abbot's attempts at bribery could not save Leicester Abbey, and it was finally surrendered to the crown for dissolution in 1538.[4]

After dissolution

After dissolution in 1538, the abbey buildings were demolished within a few years; although the main gatehouse, boundary walls and farm buildings were left standing.[4][14] The last abbot, John Bourchier, was granted the substantial pension of £200 a year, when the abbey was dissolved:[4] the largest in the Diocese of Lincoln. Payments did not continue for very long, however, as in 1552, in the reign of Henry VIII's son King Edward VI, the national finance's were so poor that all pensions over £10 were suspended, with Bourchier recorded as having not received payments for over six months.[11]

Following the Dissolution, during a period in which religion was rapidly changing in England, Bourchier managed to adapt his beliefs to stay within the hierarchy in the church: twice becoming a candidate for a bishopric, before servings as rector of Church Langton, from 1554. This benefice may have represented his true religious sympathies as the rectory was under the patronage of "zealous Catholic" Edward Griffin of Dingley Hall; although it also had financial incentive with a "wage" (income) of £60 a year: the highest in Leicestershire. Henry VIII had personally considered Bourchier for the position of Bishop of the King's proposed new bishopric of Shrewsbury but the king then decided against the bishopric's creation. In 1554 Bourchier was in touching distance of becoming a Bishop when he was suggested by Edward Griffin as a candidate for the Bishopric of Gloucester. Bourchier was even granted the income of the Bishopric in preparation for being formally appointed by Queen Mary. Mary, however, died, and Bourchier was never appointed. Mary was Catholic, where as her sister and successor, Queen Elizabeth was Protestant; Elizabeth therefore refused to appoint Mary's favoured candidates for the 5 vacant bishoprics Mary had left. Bourchier may have gotten off lightly as two other candidates were arrested.[11]

Bourchier felt unable to accept Queen Elizabeth's Acts of Settlement and Uniformity, so whilst still serving as rector of Church Langton, he decided to lay low: A list, drawn up around 1569, of pensioners of the Diocese of Lincoln lists him as "not known whether he lives or not". This continued until 1570, when his disobedience was noticed and he was deprived of the rectory. In June 1571 Bourchier sold the rights to his £200 a year pension to Sir Thomas Smyth for the sum of £900, and quietly fled abroad, probably to France or Flanders. A wealthy, but very old man, wanted by the state as a "fugitive over the sea, contrary to statute", Bourchier lived quietly abroad for his remaining years. His date and place of death is unknown, but he is thought to have lived until at least 1577, when he would have been around 84 years old.[11]

Cavendish House

Following the Dissolution of the Monasteries, Henry VIII began to lease out his newly acquired land and property to extract an income from them. Leicester Abbey was granted in 1539, on a 21-year lease, to Dr. Francis Cave, one of the commissioners who had negotiated the surrender of the abbey.[15] During this period the abbey was rapidly demolished with the stone sold to meet the high demand within the town of Leicester.[6][16]

War with France and Scotland led Henry VIII to sell of some of the religious establishments and land to raise finances quickly. Later, they were granted or bestowed to leading families who were friends or supporters of the King. These former religious establishments were frequently developed into country homes by their new aristocratic owners.[17][18] Notable examples of this include Calke Abbey,[19] Longleat House,[20] Syon House,[21] Welbeck Abbey.[22] and Woburn Abbey.[23]

Leicester Abbey followed a similar format: Dr. Cave's tenancy was cut short in 1551, when King Edward VI granted the abbey to William Parr, 1st Marquess of Northampton, brother of the former Queen Catherine Parr. Much of the abbey stone was then used to create a new mansion on the site, for the Marquess. The Marquess only held the abbey for two years: after supporting Lady Jane Grey's claim to the throne, in 1553, on the accession of Bloody Mary, he was arrested and his lands were confiscated. Mary granted the abbey and mansion to her catholic supporter Edward Hastings, 1st Baron Hastings of Loughborough, however he too fell from favour when Mary's sister Elizabeth I came to the throne.[15]

The abbey was sold to Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, in 1572, and then to his brother, Sir Edward Hastings, in 1590. It was Sir Edward who is through to have been the first of these owners to have actually lived at the abbey permanently: living in the gatehouse whilst the site was developed. Sir Edward's son Henry (who inherited the abbey in 1603) sold it to in 1613 to William Cavendish, 1st Earl of Devonshire; the mansion that had been built on the site thus became known as Cavendish House.[15][16] The 1st Earl intended the abbey to be his main residence and so started to massively extend the mansion, with a new range added to the south and a large wing to the north.[24] The family was massively wealthy with several other estates and stately homes; following the death of the 1st Earl, the family decided to use Chatsworth House as their principle residence: Cavendish House thus was only used as a stopping point on the way to London. The house gained full-time residency again in 1638, however, when it was used as a Dower house by Christiana Cavendish (née Bruce), widow of the 2nd Earl of Devonshire.[24]

In 1645, during the English Civil War, the house was used by King Charles I and the Royalist forces after they had besieging and captured Leicester. The house was looted and burned when the Royalist left and marched south towards Oxford; meeting parliamentary forces at the Battle of Naseby.[16] Cavendish House was never repaired.

The Cavendish family sold the abbey in 1733, at which point, with Cavendish House in ruins, the precinct was being used as agricultural land. By the 19th century the abbey had come into the possession of the Earls of Dysart. Lionel Tollemache, 8th Earl of Dysart, sold the land east of the River Soar (known as Abbey Meadows) in 1876; this was to allow Leicester Town Council to undertake flood prevention work. The part of this land between the river and the Grand Union Canal was developed by the Town Council into a public space known as Abbey Park, which was opened by King Edward VII (then Prince of Wales) in 1882.[24]

The remaining 32 acres (13 ha) of the abbey precinct, which included the abbey's site and Cavendish House, were donated by William Tollemache, 9th Earl of Dysart, to Leicester Council in 1925. Part of Cavendish House had to be demolished as it was found to be unsafe, however, nearly six-and-a-half years later the area was opened to the public as part of Abbey Park.[16][25]Archaeological excavations

The first excavations of the abbey took place in the 17th century, when the Dowager Countess, Christiana Cavendish, instructed her gardener to search for the body of Cardinal Wolsey and relics from the abbey; although little was found.[25]

With no above ground remains, the exact location of the abbey had been lost, and so in the 1840s, the editor of the Leicester Chronicle, James Thompson, tried, and failed, to attempt to locate the abbey church. In the 1850s the Leicester Architectural and Archaeological Society would also carry out excavations, but also failed to locate the abbey. Prior to the 9th Earl of Dysart's donation of the abbey precinct, another attempt was undertaken, but again, no trace of the abbey was found.[25]

In the interim period between the donation of the land in 1925 and opening of the abbey park, the abbey was the subject of numerous archaeological excavations, which continued into the following decade.[26] By 1930 the abbey church, and many of its associated buildings had been finally located, and it was decided (by the architect in charge of designing the new public park, William Bedingfield) that the site of the abbey should be laid out with low stone walls.[25] As the abbey's stone was "robbed", all that remained of many of the buildings were trenches: the remains of the former foundations. These trenches were "not always recognised" by the first excavators, which meant the layout of areas such as the chapter house, dormitory and kitchens was not clear.[26]

In 2002 the University of Leicester Archaeological Services decided to excavate the presumed location of the abbey's kitchens, to clarify the layout of that area of the abbey. These first excavations located both the north and south walls and a 15th–16th-century brick oven, confirming that it was indeed the kitchens. The area excavated was enlarged in 2003, with the south-west corner of the building and a second oven uncovered: this corner had not been entirely robbed of stone, with two courses of sandstone remaining. The second oven was found to contain charcoal, fragments of wheat and barley, fish-bones and hazelnuts. A drain identified in the 1930s excavation was also located, and found to contain small bones, fish-scales, and the bones of rats who had formerly lived in the drain.[26]

This excavation confirmed the kitchen was a square building measuring 11.88 metres (39.0 ft) square, with walls of between 1.32 metres (4 ft 4 in) and 1.74 metres (5 ft 9 in) thick. The ovens found in the corners of the room suggest the room was an octagonal shape internally: similar to the kitchens found at Glastonbury Abbey.[26]

From 2000 until 2008, the abbey ruins were used for training excavations for archaeology students at the School of Ancient History and Archaeology at the University of Leicester.[14]

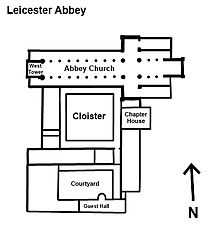

Layout

The archaeological excavations undertaken have allowed historians to calculate the layout and plan of the abbey: which were then plotted out with low stone walls, during the 1920s and 30s.[26] The abbey church was built artificially raised piece of land and is thought to have been richly decorated. It featured a tower at the west end, under which was the main entrance to the church; two large transepts, which extended beyond the church's aisles; and large secondary side chapels, situated either beside the chancel, at the east-end of the church.[27]

The cloister lay to the south of the abbey church and was flanked to the by three ranges of building. The west range contained the "lavatorium", a room used for washing; a vaulted undercroft, used for storage; and, on the first floor, the abbey's best residential accommodation, probably including that used by the Abbot. The East range contained the abbey's chapterhouse; a small room which is presumed to be either a library or a sacristry; a second larger undercroft, again used for storage; a corridor, known as the Slype, leading to the graveyard; and on the first floor were the canon's dormitory and reredorter (communal latrine). The south range contained a further undercroft; a warming house, containing a large fire for the residents to warm themselves by; and to the first floor the refectory, where the brethren ate.[27]

To the south of the cloisters lay another three ranges of buildings which were formed around cobbled courtyard. The western range of this courtyard contained the abbey's kitchens. South-east of this courtyard was a large, separate, rectangular building with a small projection facing north: this building is believed to have been the "guest hall", with the projection explained as an oriel window.[27]

The abbey sat within a large walled precinct. The original precinct walls were constructed of sandstone in the 13th century, and featured both projecting corner towers, and smaller interval towers along its length. Much of this original wall was demolished when the enclosure was enlarged to the south around the turn of the 16th century. This work was thought to have been done under Abbot John Penny and what remains of the wall is now known as "Abbot Penny's Wall". This new wall was built using red brick, rather than stone, and is decorated by forty-four different patterns or symbols, which include heraldic devices, simple patterns, and religious symbols, all of which were built into the wall using black bricks.[27]

The abbey precinct was entered through an outer gateway on the north wall of the precinct. This lead to a "halt-way" which was around 60 metres (200 ft) long, and was flanked either side by stone walls; it was enclosed at the south end by the abbey's formal Gatehouse. The original gatehouse was a single story construction of two lodges flanking the gate; but this was subsequently enlarged. The new gatehouse measured 21 metres (69 ft) by 8.5 metres (28 ft): it had round turrets at each corner, thought to contain stairs, and had "a couple of storeys" built above the gate itself. The gatehouse was then flanked to the west by what is thought to be a small, second kitchen.[27]

On the eastern side of the precinct lay the abbey's infirmary: a hospital used to care for ill or elderly canons. The infirmary was made up of two large buildings: one a chapel; the other a hall (with latrines to one end) serving as a ward. The abbey precinct also contained an almonry, where poor boys received a free education in a type of boarding school; a water mill; a dovecote; and a fishpond.[27]

The abbey's possessions

Controlled churches

Churches in Leicestershire[4]

- Asfordby, Leicestershire; (until around 1218)

- Barkby

- Barrow upon Soar

- Billesdon

- Bitteswell

- Blaby

- Cosby (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Croft

- Dishley (transferred to Garendon Abbey in 1458)

- Eastwell

- Enderby (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- "Erdesby" Arnesby? (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Evington

- Harston

- Humberstone

- Hungarton

- Husbands Bosworth

- Illston on the Hill (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Kirkby Mallory

- Knaptoft (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Knipton

- Langton

- Leicester, All Saints' Church

- Leicester, St Leonard's Church

- Leicester, St Martin's Church Since 1926, Leicester Cathedral

- Leicester, St Mary De Castro Church

- Leicester, St Michael's Church

- Leicester, St Nicholas' Church

- Leicester, St Peter's Church (Braunstone)

- Narborough

- North Kilworth

- Queniborough

- Shepshed (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Stoney Stanton (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Theddingworth

- Thornton

- Thorpe Arnold

- Thurnby (donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation)

- Wanlip

- Westcotes

- Whetstone

Churches outside Leicestershire[4]

- Sharnbrook, Bedfordshire

- West Ilsley, Berkshire

- Adstock, Buckinghamshire

- Chesham, Buckinghamshire (owned 1 half of the church)

- Youlgreave, Derbyshire

- Cockerham, Lancashire

- Great Billing (Billing Magna), Northamptonshire

- Brackley, Northamptonshire

- Farthinghoe, Northamptonshire

- Eydon, Northamptonshire

- Syresham, Northamptonshire

- Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire (church granted to the abbey in 1485, but not listed amongst its possessions in 1535)

- Clifton-upon-Dunsmore, Warwickshire

- Curdworth, Warwickshire

- Bulkington, Warwickshire

Monastic cells[4]

- Cockerham Priory, Lancashire

Manors and land

Manors held by the abbey:[4]

- Asfordby, Leicestershire; (gained from merger with The College of St Mary de Castro)

- Cawkesberia, Lancashire

- Cockerham, Lancashire

- Ingarsby, Leicestershire

- Kirkby Mallory, Leicestershire

- Knighton, Leicester; ''(donated by the 2nd Earl of Leicester upon foundation, and held until around 1218)

- Lockington, Leicestershire

Lands held by the abbey at:[4]

- Anstey, Leicestershire (donated by Robert de Beaumont, 3rd Earl of Leicester)

- Asfordby, Leicestershire; (until around 1218)

- Cossington, Leicestershire

- Pinslade, Leicestershire

- Ratby, Leicestershire

- Seagrave, Leicestershire

- Stoughton, Leicestershire

List of abbots

A list of abbots of the abbey:[4]

| Abbot's Name | Election | End of Tenure | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard | 1143 or 1144 | 1168 (approx) | |

| William of Kalewyken | 1167 or 1168 | 1178 (approx) | |

| William of Broke | 1177 | 1186 | resigned |

| Paul | 1186 | 1205 | |

| William Pepyn | 1205 | 1222 or 1224 | |

| Osbert of Duntun | 1222 | 1229 | Died in office |

| Matthias Bray | 1229 | 1235 | Resigned; Probably due to pressure from Robert Grosseteste, Bishop of Lincoln |

| Alan of Cestreham | 1235 | 1244 (?) | End of tenure estimated from the date of next abbot's election |

| Robert Furmentin | 1244 | 1247 (?) | End of tenure estimated from the date of next abbot's election |

| Henry of Rotheleye (Rothley) | 1247 | 1270 | Resigned |

| William of Shepheved (Shepshed) | 1270 | 1291 | Died in office |

| William of Malverne | 1291 | 1318 | Died in office |

| Richard of Tours | 1318 | 1345 | Died in office |

| William of Clowne | 1345 | 1378 | Died in office |

| William of Kereby | 1378 | 1393 | Died in office |

| Philip Repyngdon | 1393 | 1405 | Resigned to become "Chaplain and confessor" to King Henry IV. Repyngdon subsequently served as Bishop of Lincoln and was later created a Cardinal. |

| Richard of Rothely | 1405 | 1420 | Resigned |

| William Sadyngton | 1420 | 1442 | Died in office following allegations of Financial Impropriety |

| John Pomery | 1442 | 1474 | Died in office |

| John Sepyshede | 1474 | 1485 | |

| Gilbert Manchestre | 1485 | 1496 | Died in office |

| John Penny | 1496 | 1509 | Resigned. |

| Richard Pescall | 1509 | December 1533 or January 1534 | Resigned following pressure from John Longland, Bishop of Lincoln and allegations of impropriety. Awarded a pension of £100 a year. |

| John Bourchier | 1534 | 1538 | Was not previously a canon at the abbey, and is thought to have gained the role of Abbot through his personal contacts with Thomas Cromwell. Surrendered the abbey for dissolution in 1538, and received a large pension of £200 a year. Subsequently, twice in the running to receive a Bishopric, before becoming rector of Church Langton. Slipped abroad c.1571, after refusing to accept Elizabeth I's Acts of Settlement and Uniformity.[11] |

See also

Notes

- ↑ John Bourchier: Born around 1493 in Oakington, near Cambridge, and educated as a King's Scholar at Eton and at Kings College and St John's College, Cambridge.

References

- ↑ "Abbot Penny's Wall, Leicester", British Listed Buildings, [7 June 2013]

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Colin Platt, The Abbeys and Priories of Medieval England (Chancellor Press: London, 1995), pp. 1–5.

- ↑ "Rule of Saint Augustine", in E. Burton (ed.) Catholic Encyclopedia (Robert Appleton Company: New York, 1910) [accessed 12 June 2013]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 4.20 4.21 4.22 4.23 4.24 4.25 "Houses of Augustinian canons: Leicester Abbey", in W.G. Hoskins (ed.) and R.A. McKinley (assistant ed.), A History of the County of Leicestershire: Volume 2 (Victoria County History: London, 1954), pp. 13–19.

- ↑ "Garendon Abbey" PastScape, [accessed 12 June 2013]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 C.H. Compton, "The Abbey of St. Mary de Pratis, Leicester", in Transactions of the Leicestershire architectural and archaeological society: Volume 9, Part 3, (1902), pp. 197–204.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Henry Knighton", Encyclopedia Britannica, [accessed 1 June 2013]

- ↑ Jim Jones, "Background to The Impact of the Black Death by Henry Knighton", The Western World: HIS 101 Readings (Penguin Custom Editions: West Chester University of Pennsylvania, 2002), [accessed 1 June 2013]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 William Kelly, "Visitations of the Plague at Leicester", Transactions of the Royal Historical Society: Volume 6 (1877), pp. 395–477, (subscription required)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Henry Knighton", in E. Burton (ed.) Catholic Encyclopedia (Robert Appleton Company: New York, 1910), [accessed 1 June 2013]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Terence Y. Cocks, "The Last Abbot of Leicester", in Transactions of the Leicestershire architectural and archaeological society: Volume 58, (1982), pp. 6–19.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Sybil M. Jack, "Thomas Wolsey (1470/71–1530)", in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2004), (subscription required)

- ↑ Andrew Pettegree, "The English Reformation", BBC History [accessed 12 June 2013]

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Leicester Abbey Training Excavation", University of Leicester Archaeological Services, [accessed 18 May 2013]

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "The Story of Leicester Abbey: After the Dissolution", Leicester City Council, [accessed 8 June 2013]

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 "Abbey Park History", Leicester City Council, [accessed 16 May 2013]

- ↑ Peter Mandler, The Fall and Rise of the Stately Home (Yale University Press, 1997)

- ↑ W. T. MacCaffrey, "England: The Crown and the New Aristocracy, 1540–1600", Past and Present: No. 30 (Oxford University Press: April 1965), pp. 52–64, (subscription required)

- ↑ "Calke Abbey", English Heritage: PastScape, [accessed 24 June 2013]

- ↑ "Longleat House", English Heritage: PastScape, [accessed 24 June 2013]

- ↑ "Syon House", English Heritage: PastScape, [accessed 24 June 2013]

- ↑ "Welbeck Abbey", English Heritage: PastScape, [accessed 24 June 2013]

- ↑ "Woburn Abbey", English Heritage: PastScape, [accessed 24 June 2013]

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 "The Story of Leicester Abbey: Development of Abbey Park", Leicester City Council, [accessed 8 June 2013]

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 "The Story of Leicester Abbey: Archaeological Excavations", Leicester City Council, [accessed 8 June 2013]

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 Richard Buckley & Steve Jones, "Fire, Fast and Feast: The Kitchen of Leicester Abbey", University of Leicester, [accessed 16 May 2013]

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 "The Story of Leicester Abbey: The Abbey Buildings and Grounds", Leicester City Council, [accessed 8 June 2013]

Further reading

- James, Montague Rhodes, Catalogue of the Library of Leicester Abbey (PDF), Leicester Archaeological Society

- Story, Joanna; Bourne, Jill; Buckley, Richard (2006), Leicester Abbey: medieval history, archaeology and manuscript studies, Leicester Archaeological and Historical Society

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leicester Abbey ruins. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cavendish House. |

- Drawing showing how Leicester Abbey may have looked

- The lid of a 13th-century incense burner discovered at Leicester Abbey

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||