Legume

A legume /ˈlɛɡ(j)uːm/ is a plant in the family Fabaceae (or Leguminosae), or the fruit or seed of such a plant. Legumes are grown agriculturally, primarily for their food grain seed (e.g. beans and lentils, or generally pulse), for livestock forage and silage, and as soil-enhancing green manure. Legumes are notable in that most of them have symbiotic nitrogen-fixing bacteria in structures called root nodules. Well-known legumes include alfalfa, clover, peas, beans, lentils, lupins, mesquite, carob, soybeans, peanuts, tamarind, and the woody climbing vine wisteria. Legume trees like the Locust trees (Gleditsia, Robinia) or the Kentucky coffeetree (Gymnocladus dioicus) can be used in permaculture food forests.[1]

A legume fruit is a simple dry fruit that develops from a simple carpel and usually dehisces (opens along a seam) on two sides. A common name for this type of fruit is a pod, although the term "pod" is also applied to a few other fruit types, such as that of vanilla (a capsule) and of radish (a silique).

Nitrogen-fixing ability

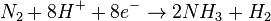

Many legumes (alfalfa, clover, peas, beans, lentils, soybeans, peanuts and others) contain symbiotic bacteria called Rhizobia within root nodules of their root systems. (Plants belonging to the genus Styphnolobium is one exception to this rule). These bacteria have the special ability of fixing nitrogen from atmospheric, molecular nitrogen (N2) into ammonia (NH3).[2] The chemical reaction is:

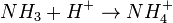

Ammonia is then converted to another form, ammonium (NH4+), usable by (some) plants by the following reaction:

This arrangement means that the root nodules are sources of nitrogen for legumes, making them relatively rich in plant proteins. All proteins contain nitrogenous amino acids. Nitrogen is therefore a necessary ingredient in the production of proteins. Hence, legumes are among the best sources of plant protein.

When a legume plant dies in the field, for example following the harvest, all of its remaining nitrogen, incorporated into amino acids inside the remaining plant parts, is released back into the soil. In the soil, the amino acids are converted to nitrate (NO3-), making the nitrogen available to other plants, thereby serving as fertilizer for future crops.[3][4]

In many traditional and organic farming practices, crop rotation involving legumes is common. By alternating between legumes and nonlegumes, sometimes planting nonlegumes two times in a row and then a legume, the field usually receives a sufficient amount of nitrogenous compounds to produce a good result, even when the crop is nonleguminous. Legumes are sometimes referred to as "green manure".

Uses by humans

Farmed legumes can belong to many agricultural classes, including forage, grain, blooms, pharmaceutical/industrial, fallow/green manure, and timber species. Most commercially farmed species fill two or more roles simultaneously, depending upon their degree of maturity when harvested.

Forage legumes are of two broad types. Some, like alfalfa, clover, vetch (Vicia), stylo (Stylosanthes), or Arachis, are sown in pasture and grazed by livestock. Other forage legumes such as Leucaena or Albizia are woody shrub or tree species that are either broken down by livestock or regularly cut by humans to provide livestock feed.

Grain legumes are cultivated for their seeds, and are also called pulses. The seeds are used for human and animal consumption or for the production of oils for industrial uses. Grain legumes include beans, lentils, lupins, peas, and peanuts.[5]

Legume species grown for their flowers include lupins, which are farmed commercially for their blooms as well as being popular in gardens worldwide.[citation needed] Industrially farmed legumes include Indigofera and Acacia species, which are cultivated for dye and natural gum production, respectively.[citation needed] Fallow/green manure legume species are cultivated to be tilled back into the soil in order to exploit the high levels of captured atmospheric nitrogen found in the roots of most legumes. Numerous legumes farmed for this purpose include Leucaena, Cyamopsis, and Sesbania species. Various legume species are farmed for timber production worldwide, including numerous Acacia species and Castanospermum australe.[citation needed]

Nutritional facts

Legumes contain relatively low quantities of the essential amino acid methionine, as compared to whole eggs, dairy products, or meat. This means that a smaller proportion of the plant proteins, compared to proteins from eggs or meat, may be used for the synthesis of protein in humans, unless other higher methionine sources are consumed which are complementary in regard to their amino acid profile. The portion of plant proteins not suitable for the synthesis of human proteins is instead used as fuel in the human metabolism. However, lower methionine ingestion has been found to actually decrease oxidative stress and damage in rodent livers and increased longevity which could possibly have implications for humans. These studies suggest that the reduced intake of dietary methionine can be responsible for the decrease in mitochondrial ROS generation and the ensuing oxidative damage that occurs during DR, as well as for part of the increase in maximum longevity induced by this dietary manipulation[6]

Nevertheless, legumes are among the best protein sources in the plant kingdom. The low concentrations of the amino acid methionine in legumes may be compensated for simply by eating more of them .[citation needed] Since legumes are relatively cheap compared to meat, eating more legumes may be an alternative to meat for some.

According to the protein combining theory, legumes should be combined with another protein source such as a grain in the same meal, to balance out the amino acid levels. Protein combining has lost favor as theory (with even its original proponent, Frances Moore Lappé, rejecting the need for protein combining in 1981[7]). A variety of protein sources is considered healthy, but they do not have to be consumed at the same meal. In any case, vegetarian cultures often serve legumes along with grains, which are low in the essential amino acid lysine, creating a more complete protein than either the beans or the grains on their own.

Common examples of such combinations are dal with rice by Indians, beans with corn tortillas, tofu with rice, and peanut butter with wheat bread.[8]

References

- ↑ Cirrus Digital: Tree Encyclopedia

- ↑ The Nitrogen cycle and Nitrogen fixation, Jim Deacon, Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology, The University of Edinburgh

- ↑ Postgate, J (1998). Nitrogen Fixation, 3rd Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge UK

- ↑ Smil, V (2000). Cycles of Life. Scientific American Library.

- ↑ The gene bank and breeding of grain legumes (lupine, vetch, soya, and beah), B.S. Kurlovich and S.I. Repyev (eds.), St. Petersburg: N. I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry, 1995, 438p. – (Theoretical basis of plant breeding. V.111)

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18252204

- ↑ Diet for a Small Planet (ISBN 0-345-32120-0), 1981, p. 162; emphasis in original

- ↑ Vogel, Steven. Prime Mover – A Natural History of Muscle. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., USA (2003), p. 301. ISBN 0-393-32463-X; ISBN 978-0-393-32463-1. in Google books

External links

| Look up legume in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Legume. |

![]() Media related to Legumes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Legumes at Wikimedia Commons

- AEP - European association for grain legume research

- - Genetic Resources of Leguminous Plants in the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry

- Lupins - Geography, classification, genetic resources and breeding

- ILDIS - International Legume Database & Information Service

- - The significance of Vavilov's scientific expeditions and ideas for development and use of legume genetic resources

- Legume Futures A major research initiative to develop novel uses for legumes in environmentally and economically sustainable cropping.

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||