Lard

| Polyunsaturated | Linoleic acid: 6–10%[1][2] |-

| Lard | |

Wet-rendered lard, from pork fatback. | |

| Fat composition | |

|---|---|

| Saturated fats | 38–43%: Palmitic acid: 25–28% Stearic acid: 12–14% Myristic acid: 1% |

| | |

| Unsaturated fats | 56–62% |

| Monounsaturated | 47–50%: Oleic acid: 44–47% Palmitoleic acid: 3% |

| Properties | |

| Food energy per 100 g | 3770 kJ (900 kcal) |

| Melting point | backfat: 30–40 °C (86–104 °F) leaf fat: 43–48 °C (109–118 °F) mixed fat: 36–45 °C (97–113 °F) |

| Smoke point | 121–218 °C (250–424 °F) |

| Specific gravity at 20 °C | 0.917–0.938 |

| Iodine value | 45–75 |

| Acid value | 3.4 |

| Saponification value | 190–205 |

| Unsaponifiable | 0.8%[2] |

Lard is pig fat in both its rendered and unrendered forms. Lard was commonly used in many cuisines as a cooking fat or shortening, or as a spread similar to butter. Its use in contemporary cuisine has diminished; however, many contemporary cooks and bakers favor it over other fats for select uses. The culinary qualities of lard vary somewhat depending on the part of the pig from which the fat was taken and how the lard was processed.

Lard production

Lard can be obtained from any part of the pig as long as there is a high concentration of fatty tissue. The highest grade of lard, known as leaf lard, is obtained from the "flare" visceral fat deposit surrounding the kidneys and inside the loin. Leaf lard has little pork flavor, making it ideal for use in baked goods, where it is valued for its ability to produce flaky, moist pie crusts. The next highest grade of lard is obtained from fatback, the hard subcutaneous fat between the back skin and muscle of the pig. The lowest grade (for purposes of rendering into lard) is obtained from the soft caul fat surrounding digestive organs, such as small intestines, though caul fat is often used directly as a wrapping for roasting lean meats or in the manufacture of pâtés.[3][4][5]

Lard may be rendered by either of two processes: wet or dry. In wet rendering, pig fat is boiled in water or steamed at a high temperature and the lard, which is insoluble in water, is skimmed off the surface of the mixture, or it is separated in an industrial centrifuge. In dry rendering, the fat is exposed to high heat in a pan or oven without the presence of water (a process similar to frying bacon). The two processes yield somewhat differing products. Wet-rendered lard has a more neutral flavor, a lighter color, and a high smoke point. Dry-rendered lard is somewhat more browned in color and flavor and has lower smoke point.[6][7] Rendered lard produces an unpleasant smell when mixed with oxygen.[8]

Industrially-produced lard, including much of the lard sold in supermarkets, is rendered from a mixture of high and low quality fat sources from throughout the pig.[9] To improve stability at room temperature, lard is often hydrogenated. Hydrogenated lard sold to consumers typically contains fewer than 0.5g of transfats per 13g serving.[10] Lard is also often treated with bleaching and deodorizing agents, emulsifiers, and antioxidants, such as BHT.[4][11] These treatments make lard more consistent and prevent spoilage. (Untreated lard must be refrigerated or frozen to prevent rancidity.)[12][13]

Consumers seeking a higher-quality source of lard typically seek out artisanal producers of rendered lard, or render it themselves from leaf lard or fatback.[9][13][14][15][16]

A by-product of dry-rendering lard is deep-fried meat, skin and membrane tissue known as cracklings.[4]

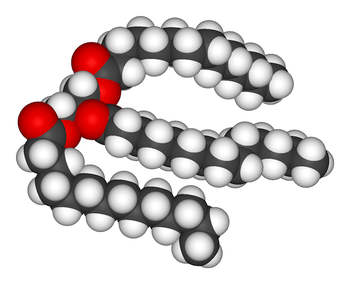

Chemistry of lard

Lard is mainly fats, which, in the language of chemistry are known as triglycerides. These triglycerides are composed of three fatty acids and the distribution of fatty acids varies from oil to oil. In general, lard is similar to tallow in its composition.[17] Pigs that have been fed different diets will have lard with a significantly different fatty acid content and iodine value. Peanut-fed hogs or the acorn-fed pigs raised for Jamón ibérico therefore produce a somewhat different kind of lard compared to pigs raised in North American farms that are fed corn.[2][18]

History and cultural use

Lard has always been an important cooking and baking staple in cultures where pork is an important dietary item, the fat of pigs often being as valuable a product as their meat.[4]

During the 19th century, lard was used in a similar fashion as butter in North America and many European nations. Lard was also held at the same level of popularity as butter in the early 20th century and was widely used as a substitute for butter during World War II. As a readily available by-product of modern pork production, lard had been cheaper than most vegetable oils, and it was common in many people's diet until the industrial revolution made vegetable oils more common and more affordable. Vegetable shortenings were developed in the early 1900s, which made it possible to use vegetable-based fats in baking and in other uses where solid fats were called for. Negative publicity was generated by the Upton Sinclar novel The Jungle which, though fictional, contained images of men falling into rendering vats and being sold as lard.

By the late 20th century, lard had begun to be considered less healthy than vegetable oils (such as olive and sunflower oil) because of its high saturated fatty acid and cholesterol content. However, despite its reputation, lard has less saturated fat, more unsaturated fat, and less cholesterol than an equal amount of butter by weight.[2] Unlike many margarines and vegetable shortenings, unhydrogenated lard contains no trans fat. It has also been regarded as a "poverty food".[4]

Many restaurants in the western nations have eliminated the use of lard in their kitchens because of the religious and health-related dietary restrictions of many of their customers. Many industrial bakers substitute beef tallow for lard in order to compensate for the lack of mouthfeel in many baked goods and free their food products from pork-based dietary restrictions (Kashrut and Halal).

However, in the 1990s and early 2000s, the unique culinary properties of lard became widely recognized by chefs and bakers, leading to a partial rehabilitation of this fat among "foodies". This trend has been partially driven by negative publicity about the transfat content of the partially hydrogenated vegetable oils in vegetable shortening. Chef and food writer Rick Bayless is a prominent proponent of the virtues of lard for certain types of cooking.[14][15][16][19]

It is also again becoming popular in the United Kingdom among aficionados of traditional British cuisine. This led to a "lard crisis" in early 2006 in which British demand for lard was not met due to demand by Poland and Hungary (who had recently joined the European Union) for fatty cuts of pork that had served as an important source of lard.[20][21]

Culinary use

Lard is one of the few edible oils with a relatively high smoke point, attributable to its high saturated fatty acids content. Pure lard is especially useful for cooking since it produces little smoke when heated and has a distinct taste when combined with other foods. Many chefs and bakers deem lard a superior cooking fat over shortening because of lard's range of applications and taste.

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 3,765.6 kJ (900.0 kcal) |

| Carbohydrates | 0 g |

| Fat | 100 g |

| - saturated | 39 g |

| - monounsaturated | 45 g |

| - polyunsaturated | 11 g |

| Protein | 0 g |

| Cholesterol | 95 mg |

| Zinc | 0.1 mg |

| Selenium | 0.2 mg |

| Fat percentage can vary. Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

| Total fat | Saturated fat | Monounsaturated fat | Polyunsaturated fat | Smoke point | |

| Sunflower oil | 100g | 11g | 20g (84g in high oleic variety[22]) | 69g (4g in high oleic variety[22]) | 225 °C (437 °F)[23] |

| Soybean oil | 100g | 16g | 23g | 58g | 257 °C (495 °F)[23] |

| Canola oil | 100g | 7g | 63g | 28g | 205 °C (401 °F)[22][24] |

| Olive oil | 100g | 14g | 73g | 11g | 190 °C (374 °F)[23] |

| Corn oil | 100g | 15g | 30g | 55g | 230 °C (446 °F)[23] |

| Peanut oil | 100g | 17g | 46g | 32g | 225 °C (437 °F)[23] |

| Rice bran oil | 100g | 25g | 38g | 37g | 213 °C (415 °F) |

| Vegetable shortening (hydrogenated) | 71g | 23g (34%) | 8g (11%) | 37g (52%) | 165 °C (329 °F)[23] |

| Lard | 100g | 39g | 45g | 11g | 190 °C (374 °F)[23] |

| Suet | 94g | 52g (55%) | 32g (34%) | 3g (3%) | 200°C (400°F) |

| Butter | 81g | 51g (63%) | 21g (26%) | 3g (4%) | 150 °C (302 °F)[23] |

Because of the relatively large fat crystals found in lard, it is extremely effective as a shortening in baking. Pie crusts made with lard tend to be more flaky than those made with butter. Many cooks employ both types of fat in their pastries to combine the shortening properties of lard with the flavor of butter.[4][25][26]

Lard was once widely used in the cuisines of Europe, China, and the New World and still plays a significant role in British, Central European, Mexican, and Chinese cuisines. In British cuisine, lard is used as a traditional ingredient in mince pies and Christmas puddings, lardy cake and for frying fish and chips, as well as many other uses.[20][21]

Lard is traditionally one of the main ingredients in the Scandinavian pâté leverpostej.

In Spain, one of the most popular versions of the Andalusian breakfast includes several kinds of mantecas differently seasoned, consumed spread over toasted bread. Among other variants, manteca colorá (lard with paprika)[27] and zurrapa de lomo (lard with pork flakes)[28] are the preferred ones. In Catalan cuisine lard is used to make the dough for the pastry known as coca. In the Balearics particularly, ensaimades dough also contains lard.

Lard consumed as a spread on bread was once very common in Europe and North America, especially those areas where dairy fats and vegetable oils were rare.[4]

As the demand for lard grows in the high end restaurant industry, small farmers have begun to specialize in heritage hog breeds with higher body fat contents than the leaner, modern hog. Breeds such as the Mangalitsa hog of Hungary or Large Black of Great Britain are experiencing an enormous resurgence to the point that breeders are unable to keep up with demand.[29]

Comparison to vegetable oils

| Vegetable oils | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Saturated fatty acids[22] | Mono- unsaturated fatty acids[22] | Polyunsaturated fatty acids | Oleic acid (ω-9) | Smoke point | ||

| Total poly[22] | linolenic acid (ω-3) | Linoleic acid (ω-6) | |||||

| Not hydrogenated | |||||||

| Canola (rapeseed) | 7.365 | 63.276 | 28.142 | 9-11 | 19-21 | - | 400 °F (204 °C)[24] |

| Coconut | 91.00 | 6.000 | 3.000 | - | 2 | 6 | 350 °F (177 °C)[24] |

| Corn | 12.948 | 27.576 | 54.677 | 1 | 58 | 28 | 450 °F (232 °C)[30] |

| Cottonseed | 25.900 | 17.800 | 51.900 | 1 | 54 | 19 | 420 °F (216 °C)[30] |

| Flaxseed/Linseed (European)[31] | 6 - 9 | 10 - 22 | 68 - 89 | 56 - 71 | 12 - 18 | 10 - 22 | 225 °F (107 °C) |

| Olive | 14.00 | 72.00 | 14.00 | <1.5 | 9–20 | - | 380 °F (193 °C)[24] |

| Palm | 49.300 | 37.000 | 9.300 | - | 10 | 40 | 455 °F (235 °C)[32] |

| Peanut | 16.900 | 46.200 | 32.000 | - | 32 | 48 | 437 °F (225 °C)[30] |

| Safflower (>70% linoleic) | 8.00 | 15.00 | 75.00 | - | - | - | 410 °F (210 °C)[24] |

| Safflower (high oleic) | 7.541 | 75.221 | 12.820 | - | - | - | 410 °F (210 °C)[24] |

| Soybean | 15.650 | 22.783 | 57.740 | 7 | 50 | 24 | 460 °F (238 °C)[30] |

| Sunflower (<60% linoleic) | 10.100 | 45.400 | 40.100 | 0.200 | 39.800 | 45.300 | 440 °F (227 °C)[30] |

| Sunflower (>70% oleic) | 9.859 | 83.689 | 3.798 | - | - | - | 440 °F (227 °C)[30] |

| Fully hydrogenated | |||||||

| Cottonseed (hydrog.) | 93.600 | 1.529 | .587 | .287[22] | |||

| Palm (hydrogenated) | 47.500 | 40.600 | 7.500 | ||||

| Soybean (hydrogen.) | 21.100 | 73.700 | .400 | .096[22] | |||

| Values as percent (%) by weight of total fat. | |||||||

Lard around the world

Lard generally refers to wet-rendered lard in English, which has a very mild, neutral flavor, as opposed to the more noticeably pork flavored dry rendered lard, which is also referred to as dripping or schmalz. Dripping (or schmalz) sandwiches are still popular in several European countries - in Hungary they're known as zsíroskenyér ("lardy bread") or zsírosdeszka ("lardy plank"), and in Germany pork fat is seasoned to make "Fettbemme". Similar snacks are sometimes served with beer in Poland, Czech Republic and Slovakia. They are generally topped with onions, served with salt and paprika, and eaten as a side-dish with beer. All of these are commonly translated on menus as "lard" sandwiches, perhaps due to the lack of familiarity of most contemporary English native speakers with dripping. Attempts to use Hungarian zsír or Polish smalec (both meaning "fat/lard") when British recipes calling for lard will reveal the difference between the wet-rendered lard and dripping.[33][34] In Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macao, as well as in many parts of China, lard was often consumed mixed into cooked rice along with soy sauce to make "lard rice" (豬油拌飯 or 豬油撈飯). And in Japan, back loin lard(fatback) is frequently used for ramen's soup, it create a thick, nutty, slightly sweet and very hearty.

Traditionally, along with peanut oil, lard is extensively used in Asian cooking as a general-purpose cooking oil, esp. in stir-fries and deep-frying.

Germany

In Germany, lard is called Schweineschmalz (literally, "rendered fat from swine") and is extremely popular as a spread. It can be served plain, or it can be mixed with seasonings: pork fat can be enhanced with small pieces of pork skin, called Grieben (cf. Jewish gribenes) to create Griebenschmalz. Other recipes contain small pieces of apple or onion.

Schmalzbrot ("bread with Schmalz") can be found on many menus in Germany, especially in grounded restaurants or brewery pubs. Schmalzbrot is often served as Griebenschmalz on rye bread accompanied with pickled gherkin.

-

Schmalz for sale in German shops with Grieben, apple, onion and herbs

Poland

In Poland, lard is often served as a starter. It is mixed with fruit, usually chopped apple, and spread on thick slices of bread.

Other uses

Rendered lard can be used to produce biofuel[35] and soap. Lard is also useful as a cutting fluid in machining. Its use in machining has declined since the mid-20th century as other specially engineered cutting fluids became prominent. However, it is still a viable option.

See also

- Lardy cake, an English bread with heavy lard content

- Schmaltz, rendered fat used for frying or as a spread on bread.

- Suet, like leaf lard

References

- ↑ National Research Council. (1976). Fat Content and Composition of Animal Products.; p. 203. Washington, DC: Printing and Publishing Office, National Academy of Science. ISBN 0-309-02440-4

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Ockerman, Herbert W. (1991). Source book for food scientists (Second Edition). Westport, CN: AVI Publishing Company.

- ↑ Davidson, Alan. (2002). The Penguin Companion to Food. New York: Penguin Books. "Caul"; p 176–177. ISBN 0-14-200163-5

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Davidson, Alan. (2002). The Penguin Companion to Food. New York: Penguin Books. "Lard"; p 530–531. ISBN 0-14-200163-5

- ↑ Ockerman, Herbert W. and Basu, Lopa. (2006). Edible rendering – rendered products for human use. In: Meeker DL (ed). Essential Rendering: All About The Animal By-Products Industry. Arlington, VA: National Renderers Association. p 95–110. ISBN 0-9654660-3-5 (Warning: large document).

- ↑ Moustafa, Ahmad and Stauffer, Clyde. (1997). Bakery Fats. Brussels: American Soybean Association.

- ↑ Rombaur, Irma S, et al. (1997). Joy of Cooking (revised ed). New York: Scribner. "About lard and other animal fats"; p 1069. ISBN 0-684-81870-1

- ↑ Vauhini Vara, Today, It's the Bacon, Not the Pigs, that Has Haight-Ashbury Agitated, Wall Street Journal A-Hed (July 10, 2013, 10:31 PM ET).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Ask Cook's: Is Lard an Acceptable Shortening?", Cook's Illustrated, November 2004.

- ↑ "Armour: Lard, 64 Oz: Baking". Walmart.com. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ "Put Lard Back in Your Larder" by Linda Joyce Forristal, Mother Linda's Olde World Cafe and Travel Emporium.

- ↑ Matz, Samuel A. (1991). Bakery Technology and Engineering. New York: Springer. "Lard"; p 81. ISBN 0-442-30855-8

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Make Your Own Lard: Believe it or not, it's good for you" by Lynn Siprelle, The New Homemaker, Winter 2006.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The Real Thing: nothing beats lard for old-fashioned flavor" by Matthew Amster-Burton, The Seattle Times, September 10, 2006.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Don't let lard throw you into a tizzy" by Jacqueline Higuera-McMahan, San Francisco Chronicle, March 12, 2003.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Light, Fluffy – Believe It, It's Not Butter" by Matt Lee and Ted Lee, New York Times, October 11, 2000.

- ↑ Alfred Thomas (2002). Fats and Fatty Oils. "Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a10_173. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ↑ Kaminsky, Peter. (2005). Pig Perfect: Encounters with Remarkable Swine and Some Great Ways to Cook Them. Hyperion. 304 p. ISBN 1-4013-0036-7

- ↑ "Heart-stopping moment for doctors as we're falling in love again with lard" by Sally Williams, Western Mail, January 5, 2006.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Lard crisis – mince pies threatened as supplies dwindle" by Helen Carter, The Guardian, November 16, 2004.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 "Chefs prize it. The French love it. The Poles are hogging it. And now Britain's running out of it." by Christopher Hirst, The Independent, November 20, 2004.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 22.5 22.6 22.7 "Nutrient database, Release 25". United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 The Culinary Institute of America (2011). The Professional Chef. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-470-42135-5.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 Katragadda, H. R.; Fullana, A. S.; Sidhu, S.; Carbonell-Barrachina, Á. A. (2010). "Emissions of volatile aldehydes from heated cooking oils". Food Chemistry 120: 59. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.070.

- ↑ "Heaven in a Pie Pan – The Perfect Crust" by Melissa Clark, New York Times, November 15, 2006.

- ↑ King Arthur Flour. (2003). King Arthur Flour Baker's Companion: The All-Purpose Baking Cookbook. Woodstock, VT: Countryman Press. "Lard"; p. 550. ISBN 0-88150-581-1

- ↑ "Manteca "Colorá", tarrina 400g - fabricantes de embutidos, chacinas, venta de embutidos" (in (Spanish)). Angellopezsanz.es. 2009-01-18. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ "ZURRAPA DE LOMO TARRINA 400 G - fabricantes de embutidos, chacinas, venta de embutidos" (in (Spanish)). Angellopezsanz.es. 2009-01-18. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- ↑ Sanders, Michael S. (March 29, 2009). An Old Breed of Hungarian Pig Is Back in Favor. The New York Times

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 Wolke, Robert L. (May 16, 2007). "Where There's Smoke, There's a Fryer". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 5, 2011.

- ↑ Fatty acid composition of important plant and animal fats and oils (German) 21 December 2011, Hans-Jochen Fiebig, Münster

- ↑ Scheda tecnica dell'olio di palma bifrazionato PO 64 (Italian)

- ↑ IMG_2116 by chrys, Flickr.com, September 16, 2006.

- ↑ "Austrian Restaurant Guide" by Keith Waclena, February 18, 2000.

- ↑ "Biofuels" by Keith Anderson, Journey to Forever: Hong Kong to Cape Town Overland (website).

External links

| Look up lard in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- "High on the Hog" by Corby Kummer, New York Times, August 12, 2005.

- "Rendering Lard 2.0" by Derrick Schneider, An Obsession With Food (blog), January 12, 2006.

- "Lard", Food Resource, College of Health and Human Sciences, Oregon State University, February 20, 2007. – Bibliography of food science articles on lard.

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||