Langmuir–Blodgett trough

A Langmuir–Blodgett trough is a laboratory apparatus that is used to compress monolayers of molecules on the surface of a given subphase (usually water) and measures surface phenomena due to this compression. It can also be used to deposit single or multiple monolayers on a solid substrate.

Description

Overview

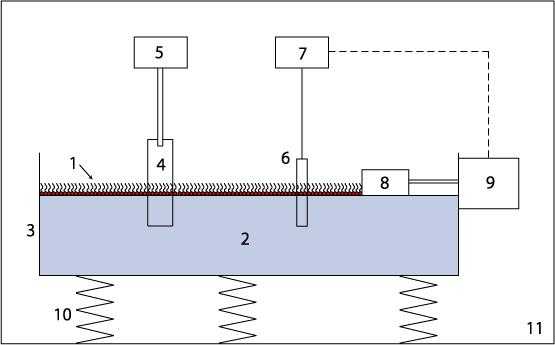

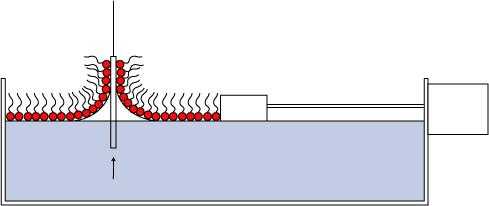

The idea of a Langmuir–Blodgett (LB) film was first proven feasible in 1917 when Dr. Irving Langmuir (Langmuir, 1917) showed that single water-surface monolayers could be transferred to solid substrates. 18 years later, Dr. Katharine Blodgett made an important scientific advance when she discovered that several of these single monolayer films could be stacked on top of one another to make multilayer films (Blodgett 1935). Since then, LB films (and subsequently the troughs to make them) have been used for a wide variety of scientific experimentation, ranging from 2D crystallization of proteins to Brewster angle microscopy. The LB trough's general objective is to study the properties of monolayers of amphiphilic molecules. An amphiphilic molecule is one that contains both a hydrophobic and hydrophilic domain (e.g. soaps and detergents). The LB trough allows investigators to prepare a monolayer of amphiphilic molecules on the surface of a liquid, and then compress or expand these molecules on the surface, thereby modifying the molecular density, or area per molecule. This is accomplished by placing a subphase (usually water) in a trough, spreading a given amphiphile over the surface, and then compressing the surface with barriers (see illustration). The monolayer’s effect on the surface pressure of the liquid is measured through use of a Wilhelmy plate, electronic wire probes, or other types of detectors. An LB film can then be transferred to a solid substrate by dipping the substrate through the monolayer.

Materials

In early experiments, the trough was first constructed from metals such as brass. However difficulties arose with contamination of the sub-phase by metal ions. To combat this, glass troughs were used for a time, with a wax coating to prevent contamination from glass pores. This was eventually abandoned in favor of plastics that were insoluble in ordinary solvents, such as Teflon (polytetrafluoroethylene). Teflon is hydrophobic and chemically inert, making it a highly suitable material, and the most commonly used for troughs today. Occasionally metal or glass troughs coated with a thin layer of Teflon are used.[1]

Barriers

Different mechanisms have been used to compress or expand the monolayers throughout the development of the LB trough. In their first experiments, Langmuir and Blodgett used flexible silk threads rubbed with wax to enclose and compress the monolayer film. Most commonly used systems are made of movable Teflon barrier blocks that slide parallel to the walls of the trough and are in contact with the top of the fluid. Another version with a variable perimeter working zone is the circular trough in which the monolayer is located between two radial barriers. A constant perimeter trough was developed later in which the barrier is a flexible Teflon tape wrapped around three pairs of rollers. One of the pairs is fixed and the other two are movable on trolleys, so that the length of the tape remains constant as the area of the working zone is changed. Some troughs allow for preparation and deposition of alternating monolayers by having two separate working zones that can be compressed independently or synchronously by the barriers.[1]

Balance

An important property of the system is its surface pressure (the surface tension of the pure subphase minus the surface tension of the subphase with amphiphiles floating on surface) which varies with the molecular area. The surface pressure – molecular area isotherm is one of the important indicators of monolayer properties. Additionally, it is important to maintain constant surface pressure during deposition in order to obtain uniform LB films. Measurement of surface pressure can be done by means of a Wilhelmy plate or Langmuir balance.[1]

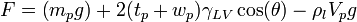

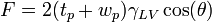

The Wilhelmy method consists of a plate partially immersed in the liquid connected to an electronic linear-displacement sensor, or electrobalance. The plate can be made of platinum or filter paper which has been presoaked in the liquid to maintain constant mass. The plate detects the downward force exerted by the liquid meniscus which wets the plate. The surface tension can then be calculated by the following equation:

![[Force\ on\ Plate]=[Weight\ of\ plate]+[Surface\ Tension\ Force]-[Buoyant\ Force]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/9/4/2/5/94259abdeb65ef2082717d7e746874d1.png)

The weight of the plate can be determined beforehand and set to zero on the electrobalance, while the effect of buoyancy can be removed by extrapolating the force back to the zero depth of immersion. Then the remaining component force is only the wetting force. Assuming that perfect wetting of the plate occurs (θ = 0, cos(θ) = 1), then the surface tension can be calculated.[2]

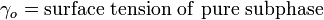

The surface pressure is then the change in surface tension due to the addition of the monolayer [3]

Where

In Langmuir’s method, the surface pressure is measured as the force exerted directly on a moveable barrier.[1]

History

One of the first scientists to describe and attempt to quantify the spreading of monolayer films on the surface of a liquid was Benjamin Franklin. Franklin described the spreading of a drop of oil onto the surface of a lake to form a surface of defined area. In addition he did experiments dropping oil onto the surface of a bowl of water and noted that the spreading action was dependent on the surface area of the liquid, i.e. by increasing the surface of the liquid it will take more drops to create a film on the surface. Franklin suggested that this spreading action was based on repulsive forces between oil molecules.[4] Much later this work was continued by Lord Rayleigh, who suggested that the spreading of oil on water resulted in a monolayer of oil molecules.[5]

A German woman and independent scientist, Agnes Pockels, wrote to Lord Rayleigh shortly after his publication in 1890. In this letter she described an apparatus she had designed to measure the surface tension of monolayers of hydrophobic and amphiphillic substances. This simple device was a trough made from a tin pan with tin inserts for determining the size of the surface and a balance with a 6 mm disk on one end to measure the force required to pull the disk from the surface. Using this device she described the general behavior of surface tension with varying surface concentrations of oil.[6]

Pockels continued her work and in 1892 published a paper in which she calculated the amount of several materials (mostly household oils) required to form a monolayer. In addition she comments on the purity and cleanliness required to accurately perform measurements of surface tension. Also in this paper she reports values of the thickness of films of various amphiphillic substances on the surface of water.[7]

In a later paper Pockels examined the effects of different ratios of hydrophobic to amphiphilic molecules on surface tension and monolayer formation.[8] After the turn of the century, Pockels’ trough was improved upon by Irving Langmuir. With this new device Langmuir showed that amphiphillic films are truly monolayers, and these monolayers are oriented on the surface such that the “active or most hydrophilic portion of the surface molecules are in contact with the liquid below whereas the hydrophobic portions of the molecules are pointing up toward the air.[9] Harkins described similar results at the same time.[10] Shortly after Langmuir described the transfer of amphiphilic films from water surfaces to solid surfaces (Langmuir, 1920). Langmuir won the Nobel prize in chemistry for this work in 1932.[1]

N. K. Adam summarized and expanded on the work of Langmuir in a series of several papers published in Proceedings of the Royal Society of London from 1921 to 1926.[11] Katherine Blodgett was a student of Irving Langmuir and in 1935 she described the deposition of hundreds of layers of amphipilic molecules onto a solid substrate in a very ordered fashion. She made final developments to the Langmuir–Blodgett trough allowing it to be used to easily transfer films to solid surfaces.[12] After the work of Blodgett the field was relatively inactive for several years until in 1971 H. Kuhn began performing optical and photoelectric experiments with monolayer assemblies using the methods of Langmuir and Blodgett.[13]

Preparations of Langmuir–Blodgett troughs

Any type of surface experiment requires maximal cleanliness and purity of components. Even small contaminations can have substantial effects on results. If an aqueous subphase is used, the water must be purified to remove organics and deionized to a resistivity not less than 1.8 GΩ-m. Impurities as small as 1ppm can radically change the behavior of a monolayer.[1] To eliminate contamination from the air, the LB trough can be enclosed in a clean room. The trough set-up may also be mounted on a vibration isolation table, to further stabilize the monolayer. The exact calibration of the electrobalance is also very important for force measurements.

Experimental preparation requires that the trough and barriers be thoroughly cleaned by a solvent such as ethanol to remove any residual organics. The liquid subphase is added to a height such that the meniscus just touches the barriers. Often it is necessary to aspirate the surface of the liquid in order to remove any last remaining impurities. The amphiphilic molecules dissolved in solvent are slowly dropped onto the liquid surface using a microsyringe, with care being taken to spread it uniformly across the surface. Some time must be taken to allow for evaporation of the solvent, and the spreading of the amphiphile. The Wilhelmy plate to be used must be absolutely clean. A platinum plate must stripped of any organics with a solvent or heated by a flame. The Wilhelmy plate is then mounted on the electrobalance such that it is immersed perpendicular to the surface of the liquid and a uniform meniscus is achieved.

The transfer of a monolayer to a substrate is a delicate process dependent on many factors. These include the direction and speed of the substrate, the surface pressure, composition, temperature, and pH of the subphase. Many different transfer methods have been devised and patented. One method involves a dipping arm which holds the substrate and can be programmed to pass through the interface from top to bottom or bottom to top at a set speed. For dipping starting from below the liquid surface, the substrate should by hydrophilic, and for dipping starting above the liquid surface, the substrate should be hydrophobic. Multilayers can be achieved by successive dipping through alternating monolayers.[1]

Uses

The LB trough has a myriad of uses, but generally takes on one of two roles. First (as described above), the trough can be used to deposit one or more monolayers of specific amphiphiles onto solid substrates. They are in turn used for different areas of science ranging from optics to rheology. For example, through devices fabricated from an LB trough Lee et al. showed in 2006 that direct electron tunneling was the mode of transportation in alkanethiol self-assembled monolayers [14]

Secondly, the LB trough can be used itself as an experimental device to test interfacial properties such as the surface tension of various fluids, as well as the surface pressure of a given system. The system can also be used as an observation mechanism to watch how drugs interact with lipids, or to see how lipids arrange themselves as the number to area ratios are varied.

Langmuir–Blodgett troughs can be used for experiments in the fabrication of Langmuir–Blodgett films and the characterization of Langmuir films. Troughs can be used to make films for the fabrication of nanoscale electronics such as graphene sheets (Li et al., 2008), and LCDs (Russell-Tanner, Takayama, Sugimura, DeSimone & Samulski, 2007). In addition films can be made of biological materials (Yang et al., 2002) to improve cell adhesion or study the properties of biofilms. An example of Langmuir–Blodgett troughs' utility in characterizing Langmuir films is the analysis of surface properties of quantum dots at the air-water interface.[15]

Buying vs. building

While it is possible to design and build a Langmuir trough by hand, this generally requires significant machining abilities, access to raw materials and advanced programming skills. As an alternative, a large fraction of laboratories purchase them prebuilt from companies that specialize in such instruments. A few of the major companies are Apex Instruments Co., Nima Technology, Kibron Inc, KSV instruments etc. Some of these companies, such as Nima Technology, focus mainly on making troughs for solid substrate deposition, offering several different models that allow for horizontal, vertical, and alternate layer dipping. Others like Kibron and KSV instruments provide “all in one” portable troughs that not only allow for substrate deposition, but also double as tensiometers and surface force measuring devices. These packages generally allow for high customizability by offering different software and hardware options such as bigger or more complicated troughs.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Chechel, O. V., & Nikolaev, E. N. (1991). Devices for production of Langmuir–Blodgett films - review. Instruments and Experimental Techniques, 34(4), 750-762.

- ↑ Erbil, Husnu Yildirim, Surface chemistry of solid and liquid interfaces, Blackwell Publishing, 2006.

- ↑ KSV Instruments, http://www.ksvinc.com/LB.htm#isotherms

- ↑ Franklin, B., Brownrigg, W., & Farish, M. (1774). Of the Stilling of Waves by means of Oil. Extracted from Sundry Letters between Benjamin Franklin, LL. D. F. R. S. William Brownrigg, M. D. F. R. S. and the Reverend Mr. Farish. Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775), 64, 445-460.

- ↑ Rayleigh, F. R. S. (1890). Proc. R. Soc, 47, 364.

- ↑ Pockels, A. (1891). Nature, 43, 437.

- ↑ Pockels, A. (1892). Nature, 46, 418.

- ↑ Pockels, A. (1894). Nature, 50, 223.

- ↑ Langmuir, I. (1917). THE CONSTITUTION AND FUNDAMENTAL PROPERTIES OF SOLIDS AND LIQUIDS. II. LIQUIDS. 1. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 39(9), 1848-1906.

- ↑ Harkins, W. D. (1917). The evolution of the elements and the stability of complex atoms. J. Am. Chem. Soc, 39, 856-879.

- ↑ Adam, N. K. (1921). The properties and molecular structure of thin films of palmitic acid on water. Part I. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series A, Containing Papers of a Mathematical and Physical Character, 99(699), 336-351.

- ↑ Blodgett, K. B. (1935). Films built by depositing successive monomolecular layers on a solid surface. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 57(6), 1007-1022.

- ↑ Kuhn, H. (1971). Interaction of chromophores in monolayer assembles. Pure and Appl. Chem, 27, 421-438.

- ↑ T. H. Lee, W. Y. Wang, and M. A. Reed, "Mechanism of electron conduction in self-assembled alkanethiol monolayer devices." pp. 21-35.

- ↑ Ji, X., Wang, C., Xu, J., Zheng, J., Gattas-Asfura, K. M., & Leblanc, R. M. (2005). Surface chemistry studies of (cdse)zns quantum dots at the air−water interface. Langmuir, 21(12), 5377-5382.

Further reading

- Langmuir, I. (1920). The mechanism of the surface phenomena of flotation. Transactions of the Faraday Society, 15(June), 62-74.

- Li, X., Zhang, G., Bai, X., Sun, X., Wang, X., Wang, E., et al. (2008). Highly conducting graphene sheets and Langmuir–Blodgett films.

- Russell-Tanner, J. M., Takayama, S., Sugimura, A., DeSimone, J. M., & Samulski, E. T. (2007). Weak surface anchoring energy of 4-cyano-4'-pentyl-1,1'-biphenyl on perfluoropolyether Langmuir–Blodgett films. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 126(24), 244706.

- Yang, W., Auciello, O., Butler, J. E., Cai, W., Carlisle, J. A., Gerbi, J. E., et al. (2002). DNA-Modified nanocrystalline diamond thin-films as stable, biologically active substrates. Nature Materials, 1(4), 253-7.