Landau pole

In physics, the Landau pole or the Moscow zero is the momentum (or energy) scale at which the coupling constant (interaction strength) of a quantum field theory becomes infinite. Such a possibility was pointed out by the physicist Lev Landau and his colleagues.[1] The fact that coupling constants depend on the momentum (or length) scale is one of the basic ideas behind the renormalization group.

Landau poles appear in theories that are not asymptotically free, such as quantum electrodynamics (QED) or φ 4 theory—a scalar field with a quartic interaction—such as may describe the Higgs boson. In these theories, the renormalized coupling constant grows with energy. A Landau pole appears when the coupling constant becomes infinite at a finite energy scale. In a theory intended to be complete, this could be considered a mathematical inconsistency. A possible solution is that the renormalized charge could go to zero as the cut-off is removed, meaning that the charge is completely screened by quantum fluctuations (vacuum polarization). This is a case of quantum triviality, which means that quantum corrections completely suppress the interactions in the absence of a cut-off.

Since the Landau pole is normally calculated using perturbative one-loop or two-loop calculations, it is possible that the pole is merely a sign that the perturbative approximation breaks down at strong coupling. Lattice field theory provides a means to address questions in quantum field theory beyond the realm of perturbation theory, and thus has been used to attempt to resolve this question. Numerical computations performed in this framework seems to confirm Landau's conclusion that QED charge is completely screened for an infinite cutoff.[2][3][4]

Brief history

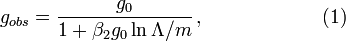

According to Landau, Abrikosov, Khalatnikov,[5] the relation of the observable charge gobs with the “bare” charge g0 for renormalizable field theories is given by expression

where m is the mass of the particle, and Λ is the momentum cut-off. For finite g0 and Λ → ∞

the observed charge gobs tends to zero and the theory looks trivial.

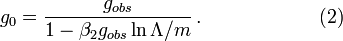

In fact, inverting Eq.1, so that g0 (related to the length scale  reveals an accurate value of gobs:

reveals an accurate value of gobs:

As Λ grows, the bare charge g0 = g(Λ) increases, to diverge at the renormalization point

This singularity is the Landau pole with a negative residue, g(Λ) ≈ −ΛLandau /(β2(Λ−ΛLandau)) .

In fact, however, the growth of g0 invalidates Eqs.1,2 in the region g0≈1, since these were obtained for g0≪ 1, so that the exact reality of the Landau pole becomes doubtful.

The actual behavior of the charge  as a function of the

momentum scale

as a function of the

momentum scale  is determined by the Gell-Mann–Low equation[6]

is determined by the Gell-Mann–Low equation[6]

which gives Eqs.1,2 if it is integrated under conditions  for

for  and

and  for

for

, when only the term with

, when only the term with  is

retained in the right hand side. The general behavior of

is

retained in the right hand side. The general behavior of  depends on the appearance of the function

depends on the appearance of the function  .

.

According to the standard classification,[7] there are three qualitatively different cases:

(a) if  has a zero at the finite value

has a zero at the finite value  , then growth of

, then growth of  is saturated, i.e.

is saturated, i.e.  for

for

;

;

(b) if  is non-alternating and behaves as

is non-alternating and behaves as

with

with  for large

for large  , then the growth of

, then the growth of  continues to infinity;

continues to infinity;

(c) if  with

with  for large

for large

, then

, then  is divergent at finite value

is divergent at finite value  and the real Landau pole arises: the theory is internally inconsistent due to

indeterminacy of

and the real Landau pole arises: the theory is internally inconsistent due to

indeterminacy of  for

for  .

.

Landau and Pomeranchuk [8]

tried to justify the possibility (c)

in the case of QED and  theory. They have noted that the growth of

theory. They have noted that the growth of  in Eq.1 drives the observable charge

in Eq.1 drives the observable charge

to the constant limit, which does not depend on

to the constant limit, which does not depend on  . The same behavior can be obtained from the functional integrals, omitting the quadratic terms in the action. If neglecting the quadratic terms

is valid already for

. The same behavior can be obtained from the functional integrals, omitting the quadratic terms in the action. If neglecting the quadratic terms

is valid already for  , it is all the more

valid for

, it is all the more

valid for  of the order or greater than unity : it gives a reason to consider Eq.1 to be valid for arbitrary

of the order or greater than unity : it gives a reason to consider Eq.1 to be valid for arbitrary  .

Validity of these considerations on the quantitative level is

excluded by non-quadratic form of the

.

Validity of these considerations on the quantitative level is

excluded by non-quadratic form of the  -function.

Nevertheless, they can be correct qualitatively.

Indeed, the result

-function.

Nevertheless, they can be correct qualitatively.

Indeed, the result  can be obtained

from the functional integrals only for

can be obtained

from the functional integrals only for

, while its validity for

, while its validity for  , based on Eq.1, may be related with other reasons; for

, based on Eq.1, may be related with other reasons; for  this result is probably violated but coincidence of two constant values in the order of magnitude can be expected from the matching condition. The Monte Carlo results [9]

seems to confirm the qualitative validity of the Landau–Pomeranchuk arguments, though a different interpretation is also possible.

this result is probably violated but coincidence of two constant values in the order of magnitude can be expected from the matching condition. The Monte Carlo results [9]

seems to confirm the qualitative validity of the Landau–Pomeranchuk arguments, though a different interpretation is also possible.

The case (c) in the Bogoliubov and Shirkov classification corresponds to the quantum triviality in full theory (beyond its perturbation context), as can be seen by a reductio ad absurdum. Indeed, if  is finite, the theory is internally inconsistent. The only way to avoid it, is to tend

is finite, the theory is internally inconsistent. The only way to avoid it, is to tend  to infinity, which is possible only for

to infinity, which is possible only for  .

It is a widespread belief that both QED and φ 4 theory are trivial in the continuum limit. In fact, available information

confirms only “Wilson triviality”, which just amounts to positivity of β(g) for g≠0 and can be considered as firmly established. Indications of “true” quantum triviality are not numerous and allow different interpretations.

.

It is a widespread belief that both QED and φ 4 theory are trivial in the continuum limit. In fact, available information

confirms only “Wilson triviality”, which just amounts to positivity of β(g) for g≠0 and can be considered as firmly established. Indications of “true” quantum triviality are not numerous and allow different interpretations.

Phenomenological aspects

In a theory intended to represent a physical interaction where the coupling constant is known to be non-zero, Landau poles or triviality may be viewed as a sign of incompleteness in the theory. For example, QED is usually not believed to be a complete theory on its own, and the Landau pole could be a sign of new physics entering via its embedding into a Grand Unified Theory. The grand unified scale would provide a natural cutoff well below the Landau scale, preventing the pole from having observable physical consequences.

The problem of the Landau pole in QED is of pure academic interest. The role of  in Eqs.1,2 is played by the fine structure constant α ≈ 1/137 and the Landau scale for QED is estimated as 10283keV/c2, which is far beyond any energy scale relevant to observable physics. For comparison, the maximum energies accessible at the Large Hadron Collider are of order 1013 eV, while the Planck scale, at which quantum gravity becomes important and the relevance of quantum field theory itself may be questioned, is only 1028 eV.

in Eqs.1,2 is played by the fine structure constant α ≈ 1/137 and the Landau scale for QED is estimated as 10283keV/c2, which is far beyond any energy scale relevant to observable physics. For comparison, the maximum energies accessible at the Large Hadron Collider are of order 1013 eV, while the Planck scale, at which quantum gravity becomes important and the relevance of quantum field theory itself may be questioned, is only 1028 eV.

The Higgs boson in the Standard Model of particle physics is described by  theory. If the latter has a Landau pole, then this fact is used in setting a "triviality bound" on the Higgs mass.[10] The bound depends on the scale at which new physics is assumed to enter and the maximum value of the quartic coupling permitted (its physical value is unknown). For large couplings, non-perturbative methods are required. Lattice calculations have also been useful in this context.[11]

theory. If the latter has a Landau pole, then this fact is used in setting a "triviality bound" on the Higgs mass.[10] The bound depends on the scale at which new physics is assumed to enter and the maximum value of the quartic coupling permitted (its physical value is unknown). For large couplings, non-perturbative methods are required. Lattice calculations have also been useful in this context.[11]

Recent developments

Solution of the Landau pole problem requires calculation of the Gell-Mann–Low function  at arbitrary

at arbitrary  and, in particular, its asymptotic

behavior for

and, in particular, its asymptotic

behavior for  . This problem is very difficult and

was considered as hopeless for many years: by diagrammatic calculations one can obtain only few expansion coefficients

. This problem is very difficult and

was considered as hopeless for many years: by diagrammatic calculations one can obtain only few expansion coefficients  , which do not allow to investigate the

, which do not allow to investigate the  function in the whole. The progress became possible

after development of the Lipatov method for calculation of large orders

of perturbation theory:[12] now one can try to interpolate the known

coefficients

function in the whole. The progress became possible

after development of the Lipatov method for calculation of large orders

of perturbation theory:[12] now one can try to interpolate the known

coefficients  with their large order behavior and

to sum the perturbation series. The first attempts of reconstruction of the

with their large order behavior and

to sum the perturbation series. The first attempts of reconstruction of the

function witnessed on triviality of

function witnessed on triviality of  theory. Application of more advanced summation methods gave the exponent

theory. Application of more advanced summation methods gave the exponent

in the asymptotic behavior

in the asymptotic behavior  a value close to unity. The hypothesis for the asymptotics

a value close to unity. The hypothesis for the asymptotics  was recently confirmed analytically for

was recently confirmed analytically for  theory and QED

[13]

.[14]

Together with positiveness of

theory and QED

[13]

.[14]

Together with positiveness of  , obtained by summation of series, it gives the case (b) of the Bogoliubov and Shirkov classification, and hence the Landau pole is absent in these theories. Possibility of omitting the quadratic terms in the action suggested by Landau and Pomeranchuk is not confirmed.

, obtained by summation of series, it gives the case (b) of the Bogoliubov and Shirkov classification, and hence the Landau pole is absent in these theories. Possibility of omitting the quadratic terms in the action suggested by Landau and Pomeranchuk is not confirmed.

References

- ↑ Lev Landau, in Wolfgang Pauli, ed. (1955). Niels Bohr and the Development of Physics. London: Pergamon Press.

- ↑ Göckeler, M.; R. Horsley, V. Linke, P. Rakow, G. Schierholz, and H. Stüben (1998). "Is There a Landau Pole Problem in QED?". Physical Review Letters 80 (19): 4119–4122. arXiv:hep-th/9712244. Bibcode:1998PhRvL..80.4119G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.80.4119.

- ↑ Kim, S.; John B. Kogut and Lombardo Maria Paola (2002-01-31). "Gauged Nambu–Jona-Lasinio studies of the triviality of quantum electrodynamics". Physical Review D 65 (5): 054015. arXiv:hep-lat/0112009. Bibcode:2002PhRvD..65e4015K. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.65.054015.

- ↑ Gies, Holger; Jaeckel, Joerg (2004-09-09). "Renormalization Flow of QED". Physical Review Letters 93 (11): 110405. arXiv:hep-ph/0405183. Bibcode:2004PhRvL..93k0405G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.110405.

- ↑ L. D. Landau, A. A. Abrikosov, and I. M. Khalatnikov, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 95, 497, 773, 1177 (1954).

- ↑ Gell-Mann, M.; Low, F. E. (1954). "Quantum Electrodynamics at Small Distances". Physical Review 95 (5): 1300–1320. Bibcode:1954PhRv...95.1300G. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.95.1300.

- ↑ N. N. Bogoliubov and D. V. Shirkov, Introduction to the Theory of Quantized Fields, 3rd ed. (Nauka, Moscow, 1976; Wiley, New York, 1980).

- ↑ L.D.Landau, I.Ya.Pomeranchuk, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 102, 489 (1955); I.Ya.Pomeranchuk, Dokl. Akad. Nauk SSSR 103, 1005 (1955).

- ↑ B.Freedman, P.Smolensky, D.Weingarten, Phys. Lett. B 113, 481 (1982).

- ↑ Gunion, J.; H. E. Haber, G. L. Kane, and S. Dawson (1990). The Higgs Hunters Guide. Addison-Wesley.

- ↑ For example, Heller, Urs; Markus Klomfass, Herbert Neuberger, and Pavols Vranas (1993-09-20). "Numerical analysis of the Higgs mass triviality bound". Nuclear Physics B 405 (2–3): 555–573. arXiv:hep-ph/9303215. Bibcode:1993NuPhB.405..555H. doi:10.1016/0550-3213(93)90559-8. , which suggests MH < 710 GeV.

- ↑ L.N.Lipatov, Zh.Eksp.Teor.Fiz. 72, 411 (1977) [Sov.Phys. JETP 45, 216 (1977)].

- ↑ I. M. Suslov, JETP 107, 413 (2008); JETP 111, 450 (2010); http://arxiv.org/abs/1010.4081, http://arxiv.org/abs/1010.4317.

- ↑ I. M. Suslov, JETP 108, 980 (2009), http://arxiv.org/abs/0804.2650.