Lambroughton

| Lambroughton | |

Lambroughton | |

| OS grid reference | NS402439 |

|---|---|

| Council area | North Ayrshire |

| Lieutenancy area | Ayrshire and Arran |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Scottish |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| EU Parliament | Scotland |

| UK Parliament | Central Ayrshire |

| Scottish Parliament | Cunninghame South |

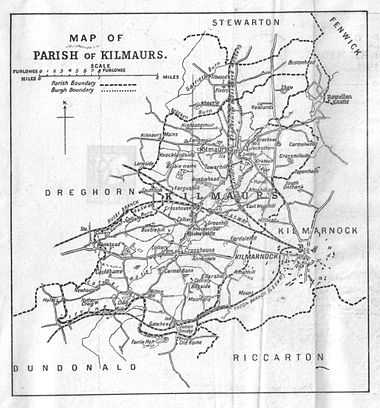

Lambroughton is a village in the old Barony of Kilmaurs, North Ayrshire, Scotland. This is a rural area famous for its milk and cheese production and the Ayrshire or Dunlop breed of cattle.

Origins of the name

The surname and place name both appear to be derived from that of the clan McLamroch. Only a handful of people in Great Britain have that name today. The Scottish Genealogical Society refer to a family tree which derives the McLamroch's from the Cunnigham (Cunningham) family.[1] McLandsborough, Landsborough, Landsburgh, Lamroch, Lamrochton, Lamrock, Lamberton are all variants. The lands of Lambroughton lie in the parish of Dreghorn and have therefore given rise to a fairly common personal name. Several graves in the neighbouring parish church of Kilmaurs: St Maurs-Glencairn carry the name Lamberton, a William Lambroughton was the 'Kilmaurs poet' (See Additional notes) and the name is now found all over the World. A Laird of Lamrochton is recorded in the 14th. century. In 1691 the surname Lamrochtoun is found in use only for Kilmaurs in the Ayrshire Hearth Tax records.[2]

The place name has many variants, such as, Lambruchton, Lambrochton, Lamrochtoune (1544), Lambrachton, Lambrachtoun, Lambrachtoune (1332),[3] Lambroughtoune (1794), Lambriegton, Lambughton (1672), Lambructon (1669),[4] Lammerachtounhead (1745–55), Lamburghtonn (1776),[5] Lambroychtoune (1561), Lambrieghton and Lambristoune. The 'Mc' part of the name was dropped and Lamrochton became Lambroughton after passing through several intermediate stages. At this time, due to Queen Margaret, niece of Edward the Confessor and the second wife of Malcolm III (1058–1093), it was customary to anglicise surnames and many families did so, such as Andrews, Adams, Campbell, etc. The Highlanders called her the 'Accursed Margaret', to the Lowlanders she became St. Margaret.[6] There is a parallel to this in the Isle of Man where few signs remain of the old Manx language patronymic system remain. Today (2006) there are several farms with 'Lambroughton' incorporated, namely 'Townhead of Lambroughton', 'East Lambroughton', 'West Lambroughton' and 'Mid Lambroughton'. Timothy Pont's map of 'Cuninghamia', surveyed in the early 17th century (1604–1608), but not published until the 1654 by J.Blaeu indicates the place names of 'Lambrochmill', 'Mains of Lambrochton' and 'Lambrochton B.(bridge?)'. Ainslie in 1821 only names Lambriegtonend and Lambriegton for Mid Lambroughton.

Many of the abbreviations give a soft pronunciation to the 'gh', as in 'Lamberton', however the original Scots pronunciation may have been more like the 'och' in 'loch', thus 'Lambrochton' would be closer to the original.

The origins of the name Cunninghame

Robertson states that the name is variously described as originating from the Danish appellation 'King's House' or the Gaelic Cuineag, a 'milkchurn'. In this context Pont in 1604 records that the parishes of Dunlop and Stewarton produced very significant amounts of butter, with "One aker of ground heir zeilding more butter then 3 akers of ground in aney ye nixt adiacent countreyes."

Another possibility stated by McNaught[7] is that the name derives from the coney or rabbit country. This is not as unlikely as it might sound, for Hart-Davis points out that no Anglo-Saxon or Celtic word for 'rabbit' exists and no mention is made of them in the Domesday Book of 1086, also 'coneys' were adults and the term rabbits was only used for the young. The Normans, such as Warnebald, introduced the species for their meat and fur. They were either kept in warrens within stone walls or kept on small islands, such as on Little Cumbrae.[7] Only later did they escape into the wild and become a successful member of the British fauna. Black rabbits were especially valued for their fur. Significantly a pair of coneys are the supporters on the Earls of Glencairns coat of arms. Mackenzie also sees the name as coming from either Coning, a rabbit or Cyning, a king; preferring King as denoting a Royal manor during the Anglo-Saxon sovereignty over Galloway. The use of a pictorial rhyming pun is called a rebus and is very common on coats of arms. A Charter of the time of Mary, Queen of Scots, refers to Eglinton's 'cunningaries,' Scots for rabbit-warrens.[8]

Another theory is that the name derives from that of Cunedda ap Edern who lived in the mid 5th. Century. The Latin form of his name is Cunetacius and the English is Kenneth. He is also known as Cunedda Wledig ('the Imperator') as he was an important early Welsh or Brythonic leader, originally from the area known as Manau Goddin with its capital at Dunedin or as it is now known, Edinburgh. He was a famous leader and the progenitor of the royal dynasty of Gwynedd. His name 'Cunedda' derives from the Brythonic word counodagos, meaning 'good lord'. He drove the Irish out of North Wales and left behind a reputation which has become bound up in myth and legend.

By the early 13th century the family had taken the surname of Cunynghame now Cunninghame. Paterson,[9] a man brought up at Struthers Farm in Kilmarnock parish, argues that the original name was Cunigham and that local people pronounced it that way until relatively recently. McNaught in 1912 confirms this and states that the name all over Scotland is still pronounced "Kinikam". A "cunningar" is Scots for a rabbit-warren and a variant place name is 'Kinniker'.[10] Cunninghamhead Moss was still referred to as Kinnicumheid Moss in the 18th century.[11] The Gaelic pronunciation of Cunninghame could also be taken as sounding not unlike "Kinikam".

Robertson points out that the various branches of the family spell their name differently; as Cunninghame for Glencairn and Corsehill, Cuninghame for Caddel and Monkredding, Cunningham for Baidland and Clonbeith and finally Cuningham for Glengarnock. It is said by Chalmers in his Caledonia as quoted by McNaught,[7] that the settlement of Kilmaurs was known as Conygham until it was changed sometime in the 13th century.

The modern view is that the name Kilmaurs is derived from the Gaelic Cil Mor Ais, meaning Hill of the Great Cairn.[12] Kilmaurs was known as the hamlet of Cunninghame until the 13th century.[13]

The Cunningham family's connection with Lambroughton

The feudal allocation of tenements to the vassals of the overlord, De Morville, was carried out very carefully, with the boundaries being walked and carefully recorded.[14] The term 'ton' at this time was added to the site of the dwelling house, not necessarily a grand stone-built structure, which was bounded by a wall or fence. The tenements were held in a military tenure, the land being in exchange for military assistance to the overlord. In later years the military assistance could be exchanged for financial payment. Robertson[15] records Lambruchton as one of the many lands held by the De Morvilles.

It is likely that the Lambroughton mentioned in the early records refer to the site the farm now known as Townhead of Lambroughton. Pont records a Mains of Lambrochtoun in 1604 and as the term 'mains' refers to the home farm of an estate, cultivated by or for the 'owner', then we can assume that the main dwelling was here or hereabouts. The 'place ' of Lambroughtoun is mentioned in 1544. It should be noted that it was the custom of a landowner or farmer to take the name of the land which he owned or cultivated.

Warnebald/Wernebald or Vernebald from Flanders was a vassal of Hugo de Morville (died 1202), hereditary Constable of Scotland. They both came to Scotland via Burg in Cumbria. Hugo, who came from Morville in the department of Manche in Normandy, granted the Barony of Kilmaurs to Wernebald in around 1140 and Lambrochton was the most important of the lands given in this grant[16] The De Morvilles also held Appleby and Pendragon Castles and other lands in Cumbria at this time.[17]

The earliest reference to the use of the Lambroughton name in any form of personal context seems to be that of a Gulielmus (William) de Lambristoune who was a witness to a charter conveying the lands of Pokellie (Pokelly) from Sir Gilchrist More to a Ronald Mure at a date around 1280. We do not know if this Guilielmus was a Cunninghame, however we are told by Timothy Pont the cartographer and topographer in the early 17th century that Lambrouchtoune was the ancientest inheritance of the predecessors of the Cunninghames of Glencairne. Kennedy records that Lambroughton was part of the dowry of a grand-daughter of the High Constable.[18]

The Barony of Kilmaurs was composed of the lands of Buston, also Bowieston and Buythstoun (now Buiston), Fleuris (now Floors), Lambroughton, Whyrrig, (now Wheatrig) and previously Quhytrige,[19] and Southwick or Southuck (now South Hook). South Hook (previously also Southeuck or Seurnbenck) is near Knockentiber and was part of the tenement of Lambroughton within the barony, showing that the lands of Lambroughton were fairly sizeable at one time.

King Alexander II (1198–1249) gave the whole barony of Kilmaurs to Henry de Conyghame and then it is recorded that all the lands of Cunyngham were granted to a Robert Stuart, son of Walter (before 1321).

The Barony was originally held by the powerful De Morville family who were related to John Baliol through his mother, Devorgilla, a daughter of the De Morville family and the founder of Sweetheart Abbey in Kirkcudbright. Another view is that Devorgilla was the daughter of Alan of Galloway and was not a de Morville.[20] However her nieces Margaret and Elena (Ela), married into the de Ferrers and de la Zouche families, related to the De Quinceys, Earls of Winchester from whom the Lambrochtoun lands may have been inherited.[3] It is pertinent to point out that lineage and relationships are made more difficult by the not infrequent habit of indirect male heirs assuming the names and titles of their indirect family inheritances. The De Morville's were also related to another claimant for the Scottish crown, John Comyn. John Baliol's nephew. Bruce and his supporters murdered John Comyn in the church at Dumfries. Baliol lost the crown to Robert the Bruce, who ruled from 1306–1329, then rewarded his loyal supporters, the Cunninghames, by granting the lands of Lambrachton and Polquharne (also Polcarn) to a Hugo de Cunynghame of Lambroughton who died without issue and in 1321 the king then gave the lands of Lambrachton and Grugere to Robertus de Conyngham of Kilmaurs.[3] This Robert was then known as Robert de Cunninghame of Lambroughton.

Alan de La Zuche and William de Ferreres (cousins) who had held these lands previously from Hugh de Morville (see Floors Farm) were dispossessed. Alan de La Zuche descendants gave rise to the Ashby De La Zuche family and town, whilst the Marquis of Townsend is the direct descendant of William De Ferreres. The De Ferreres family came over from Ferrieres-St.Hilaire in Normandy with Duke William and had extensive lands in England, founding Merevale, Darley & Abbey Dore abbeys.[citation needed] The 1328 Northampton peace treaty between Scotland and England did not return lands to those who had suffered forfeiture.[21] During the reign of Edward II the dispossessed lords, including de la Zouche and De Ferrers, under the leadership of Edward Balliol invaded Scotland and may have regained their lands temporarily.[22] In 1363 under the treaty of David II with Edward III of England, the lord 'Ferrars' was still trying to repossess lands in Scotland.[23]

The importance of the tenement is illustrated by the efforts made by dispossessed lords to recover them and by fact that William Cunninghame of Lamberton (see 'Lamberton in the Scottish Borders') (1297–1328) was Bishop of St.Andrews in 1322[7] and he was the 'Guardian of Scotland' for a time during the inter-regnum when Cumyn, Baliol, Bruce and others were disputing the crown of Scotland.[24] At the battle of Bannockburn he never failed his younger friend, indeed, it was he who observed the crucial moment in battle where the Scots, greatly outnumbered, were beginning to flag. It was at that point he decided to take a hand and leaving the safety of the Scots baggage train, he led the charge of the 'small folk'—women, old men and others who had been injured or otherwise excluded from the fighting—armed with sticks, kitchen knives, meat cleavers, indeed, anything they could lay their hands on—to the aid of the flagging Scots. It was this crucial intervention which finally turned the battle. From a distance, the English mistook them for a fresh army, and the sheets and blankets they had tied to poles to be banners and flags. In that moment, the Battle of Bannockburn was won.

William was also charged with the responsibility for disbanding the Knight's Templars in Scotland and probably allowed them to escape gaol and execution in exchange for finance, weapons and other assistance against the English. He died in 1328 and was buried at St. Andrews.

King Robert III (1340–1406) granted the lands of Lambrochton and Kilmaurs to Sir William Cuninghame. Robert Stewart, first Duke of Albany (Brother of King Robert III) later granted these lands to Robert Cuninghame. In 1413 Sir William de Cunynghame[7] Lord of Kilmaurs endowed the collegiate church at Kilmaurs with all of his lands of the Southuck (now South Hook) within the tenement of Lambrachtoun and other properties. The income was to pay for three priests to say prayers for the safety of his soul, that of his parents and of Hervy the church's founder, etc. In 1346 a William Baillie, the Baillie of Lambistoun or Lambimtoun, vulgarly called Lamington is listed by Dalrymple[25] amongst the prisoners taken by the English at the Battle of Durham which had taken place on 17 October of that year. He was in the company of a Thomas Boyd of Kilmarnock and Andrew Campbell of Loudoun. Details of the Lairds of Lambroughton are contained within the papers of Dick Cunyngham (1627) of Prestonfield, Midlothian.[26]

The Cunninghame chiefs had only a slight connection with the barony of Kilmaurs after 1484 when Finlaystone became the family seat. Sir William Cunningham of Kilmaurs had married Margaret Denniston, sole heir to Sir Robert Denniston in 1405. The dowry included the baronies of Denniston and Finlaystone in Renfrewshire, the lands of Kilmaronock in Dumbartonshire, and the barony of Glencairn in Dumfrieshire.[27] In 1616 many parcels of land belonging to the Barony of Kilmaurs were disposed of, together with Kilmaurs place and other possessions.[7] In 1520 Lambrochton was acquired by Hugh, first Earl of Eglintoun (see Townhead of Lambroughton). Paterson (1866) states that Lambruchton was one of the lands inherited by Alexander Cuninghame of Corshill in May 1546, held by right of Royal Charter.

In 1632 Alexander Conyngham had Lambroughton and Crumshaw Mills; in 1640 Johne Conyngham held part of the lands of Langmure, probably including Lambroughton, at a valuation of £200 a year, the rest being held by Stewart Fergushill at £66, 12 shillings and 10 pence.[28]

In 1667 Mr. John Cuninghame of Lambrughton (later Sir John) was one of the thirteen Commissioners of Supply for Ayrshire. The main purpose of the commissioners was to organise the collection, in an effective manner, of taxes. Their significance was that they held their power directly from royal authority and not as a feudal right. They later took on the role of organising education and the control of roads, bridges and ferries. They were replaced in 1890 by the County Councils, but survived with a few vestigial functions until 1929.[29]

Sir John Cunninghame of Lambroughton was the patron of Dreghorn and Kilmaurs kirks in 1670. He was an advocate, one of the most distinguished lawyers of his day,[30] and obtained the sanction of parliament to use vacant stipends for the purpose of repairing churches and manses in these parishes.[7] He already possessed the lands of Lambruchton, before acquiring the in 1683 the barony of Caprington from John Earl of Glencairn.[30] John Cuninghame of Broomhill, Lambructon, and Caprington was created a baronet on 21 September 1669 to him and his male heirs only.[4][31] and died 1684, succeeded by his son, Sir William, who is titled 'of Caprington' only. The history of the family is that of the Cunninghame's of Caprington from this point on.[32]

In 1675 Sir John Cunninghame Bart., conveyed to Robert Cunningham, druggist / apothecary, Edinburgh, the lands of 'Langmuir, Langsyde, Auldtoun and Lambrochtoune in whose family they seem to have remained until 1820, when George Cunninghame was the owner. This same Robert was cousin-german to Anne, daughter of Sir Robert Cunynghame of Auchinharvie and inherited the lands of Crivoch-Lindsay, together with Crivoch corn mill and Fairlie-Crivoch, including the Chapel lands and glebe of Fairlie-Crivoch. See Chapeltoun.

Various mentions are made to a Thirdpart, such as in 1574 when it was a thirdpart or 5 merkland of Lambroughtoun Robertoune, being in that barony and not part of the Barony of Kilmaurs.[33]

It is likely that the Lambroughtons were a cadet family of the Cunninghames of Kilmaurs.

Townhead of Lambroughton (Lambrochtoune) itself must have passed to the Longmuirs by 1734 as it is recorded by McNaught that Gabriel Longmuir of what is now High Langmuir owned the farm at this date.

Legend of Friskin and Malcolm Canmore

One version of the story is given by Robert Cunnighame in 1740. In his manuscript, entitled the Right Honorable the Earl of Glencairn's family, MacBeth murders his cousin, King Duncan I and the king's son, Malcolm Canmore (Great chief, long neck or 'big head' in Gaelic) tries to reach temporary safe refuge in his castle of Corsehill (also Crosshill) outside Stewarton.

In another version of the story, it is stated by Frederick van Bassen[34] who was a learned Norwegian, that the saviour of Malcolm was actually a Malcolm, son of Friskin, however in other respects the story is the same.

This story does not fit with the historical record, however it is of ancient origin and a grain of truth must in some way relate it to real events. The lands given to the family would have included the tenement of Lambroughton.

Friskin or Freskin is a Fleming name and many Flemings were granted lands in Scotland in the ealry days of feudalism, such as Freskin who was granted land in Moray, and founded the families of Murray and Sutherland.[35]

Lambroughton and the murder of Thomas Becket

In 1887 it is recorded[7] that a manuscript containing the genealogy of the Cunninghames of Glencairn states the following;-

"The founder of the family of Cunningham was Neil Cunningham, designed governor of Lambroughton, born in England in the year of our Lord, 1131. Being ane English gentleman , and come of ane ancient family, he, together with others, was enticed or rather forced by his lawful prince, King Henry II of England, his private orders, to commit murder upon the person of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, which he accordingly put in execution 30 December 1172, after which he was held in so great hatred by his countrymen that for shelter from their fury he flees to Scotland and takes up habitation in the country of Cunningham, after which he becomes in great favour with our King for his good service in saving the King's life at ane battle in Cunningham at Kilmairs, where he was enclosed by his enemies, and for which good service in saving the King's life he obtained from the King the lands of Lambroughton, and was made sole governor thereof." This Neil married the daughter of the Laird of Arnot and had four sons.

This version does not agree with the others, however it does confirm an ancient battle in the vicinity of Kilmaurs, involving King Malcolm III.[34]

Lamberton in the Scottish Borders

Logan Mack [36] records the existence of the village of Lamberton in the Scottish Borders at the extreme north and east end of the border march, near Berwick. It was destroyed in 1548 by a raid led by the Earl of Hertford and only a church and a few farms of that name remain today. It is suggested that the name came from the Saxon first name Lambert and the placename was in use by 1098. We know of a William, Henry and a John de Lamberton; Logan Mack states that it probably from this ancient family that the famous William Lamberton, Bishop of St. Andrews arose. This bishop's special fame derives from his role in advising and assisting William Wallace and especially King Robert the Bruce in his ultimately successful efforts to throw off the English yoke.

Only further research will finally settle the question of any relationship between the two Lambertons, however McNaught[7] states that William was a Cunninghame of Lambroughton. Details from the National Dictionary of Biography seem to clarify his origins in the Lamberton family, originally from Berwickshire, but holding lands in north-east Scotland by the late 12th century and later in Stirlingshire.

Townhead of Lambroughton

Armstrong's map[37] of 1775 shows a Lamberton, Pont's map of the 17th century shows a Mains of Lambrochton, Arrowsmith[38] in 1807 shows Lamberton, Ainslie's map[39] of 1821 shows a Lambrieghtonend and finally Aitken's map[40] of 1829 gives a Townhead of Lamberton, occupied by a Mr. Orr Esq. References to Lambroughtonend seem to be a confusion with the old farm of that name which was abandoned when East Lambroughton was built.

By 1866, Alexander Orr Esq. is the owner of Townhead Of Lambroughton.[28] The name Lambroughton Head is however indicated by the 1858 and 1895 OS maps, but finally by 1897 the 6 inches to the mile OS shows the name Townhead of Lambroughton, which it has retained ever since. In 1561, the site is referred to as the Town of Lambroychtoune.[41]

The old Stewarton to Irvine road seems to have run through the group of buildings at Lambroughton and as it no longer does, then its course would probably have been altered when the turnpike road was constructed in the 1760s. The old entrance onto the Chapeltoun to Kilmaurs road is no longer in use, but it may represent part of the original route of the 1775 road and some evidence of a road running through the farmyard and out to run behind Laigh Castleton farm is evident from ground conditions.[42] A lane also ran off a crossroads (now a 'T' junction of sorts) near Floors and ran down to the farm as shown on Ainslie's 1821 map. A lane ran from Mid Lamb. directly to Townhead of Lamb until the turnpike was constructed.

McNaught[7] states that one Hugh Lamberton, a merchant of Glasgow, left £300 in the early 19th century as the Lamberton Mortification to be used to provide fuel, food or clothing for the local poor. He may have come from Townhead of Lambroughton, as he was obviously a man with strong local connections.

A marriage stone built into a wall on the farm reads 'AL MR 1707'. This may be Alexander Langmuir; however, it predates the ownership of the farm by his father Gabriel Longmuir in 1734. Another stone bears a date which seems to be 1724 and was part of a two-story building demolished in 2006.

Reid's Family History[43] gives the occupants, but not necessarily the owners, with Alexander Langmuir in 1532, John in 1603, Alexander in 1609 and his first wife Isabel (nee Langmure) and daughter Isabel. His second wife was Janet Tod. In 1666 we have Alexander Langmure, John Langmuir in 1710, Alexander in 1721, John Langmuir in 1730 and Gabriel Langmuir in 1730, who as stated below, was an owner occupier. Alexander Langmuir was living there in 1762 and in 1794 Alexander Longmuir was referred to in papers held in the Scottish National Archives as a 'Portioner' of Lambroughton. The records of Dreghorn Parish church give these dates as the family tradition was to become church elders.

Samuelle Moors of Lambroughtoune purchased lands in Chapletoune from John Faulds of Kingswell Muir in 1709, with Thomas Brown as the tenant. An Adam Moor had been a previous occupant.[44]

Townhead of Lambroughton (Lambrochtoune) itself must have passed to the Longmuirs by 1734 as it is recorded by McNaught that Gabriel Longmuir of what is now High Langmuir owned the farm at this date. In 1811–13, Alexander Longmuir held the property, his wife being Margaret Roid (Reid). In 1820, Robertson gives Lambertonhead a rental value of £118, the proprietor being William Orr, Esq.

As stated, Lambrouchton-head was owned in 1734 by Gabriel Longmuir[28] who was succeeded by Alexander Longmuir, whose sister, Margaret, married William Orr in Langmuir, Kilmaurs. Their eldest son William Orr succeeded to the property in 1808 and built the present mansion house. William married Grizell Lock of Hollybush in Paisley and had eight sons and two daughters. The eldest son, Alexander inherited the property in 1856 and married Margaret Gilmour of Dunlop. They had seven children who inherited the property conjointly. Alexander Orr Esquire of Lambroughton Mains died on 5th. June 1860, aged 62, however Margaret lived on until the age of 92, dying on 22 December 1909. They were both buried in Dreghorn parish churchyard.

Townhead of Lambroughton is include in Davis's book and he records it as being a small estate long independent of the larger estates which surround it and comments on the old building of 1724.

The placename changed from Mains of Lambroughton in 1604, to Lambroughton-Head in 1858 and finally to Townhead of Lambroughton by 1897. The name change reflects the status of the site, from firstly being a 'ton' of the tenement held by the feudal vassal to a small estate amongst other Lambroughton farms to a modern farm amongst others of equal status. The usage of Townhead, Mid and Townend is quite commonly found when the same identifying 'surname' name is used.

Langmuir and its connection with Townhead of Lambroughton

The estate of Langmuir (now High Langmuir) used to include Auldtoun (previously Auldtoune), Langsyde, part of Lambroughton and also part of Busbie.[7]

Lambroughtonend

The 1789 Montgomerie Estate Plan by Ainslie shows a farm by this name existing on the other side of the road from the existing East Lambroughton, reached by a lane branching off the toll road. Its lands encompass all of the field running down to the woods. It appears that this farm was demolished and East Lambroughton was built to replace it, recycling worked stones from the old farm can be seen in the present building (2010).[45] The 'footprint' and some foundations stones of the old Lambroughtonend Farm can still be seen in the field (2010), next to the site of a small burn, now piped down to the Lochrig Burn.[45] William Roy's map of 1745 - 47 shows a roughly 'L' shaped farm and tree belts at this location.[46]

East Lambroughton Farm

Thomson's map of 1828 does not mark this farm, however Aitken's map of 1829 names the farm as 'Lamberton', however by 1858 the name becomes East Lambroughton, presumably to clarify potential confusion with the other farms, as indicated by the 6 in. to the mile OS map. East Lambroughton is shown but not named on the 1895 OS. East Lambroughton is not marked on the Pont's (1604) or Armstrong's (1775) map.

James Nairn was christened on 30 October 1788 in Stewarton. James lived in East Lambroughton in the 1841 and 1851 censuses. He died there on 17 October 1861. No record of marriage or children exists. The parents of local character, businessman, steam, tractor and agricultural implements enthusiast Frank 'Rob Roy' Neill lived here for a short while after they were married, moving to Kilmaurs after about a year. Frank's father was a Traction engine driver as witnessed by the Birth Certificate of his son. The father of Davie Smith of Peacockbank Farm was born here. Mr. Tom & Mrs. Nancy Forrest lived at East Lambroughton Cottages when they were first built. The Forrests moved to Byres Farm.

The farmhouse was eventually divided into three separate 'flats' with the three families being McNiven, Rae and Kelly.[42] The McNiven's were the first occupants of Number 3, Chapeltoun Terrace and the Rae's were the first to occupy Number 4. Jimmy Rae had been the Ploughman at Castleton Farm. These council built houses are just across the field from the old farm buildings. Number 3 was later occupied in their retirement by John and Minnie Hastings of West Lambroughton and the Bull family lived at Number 1.

A traveller named Stanley Macallan lived as an unofficial occupant of the upper room for a while in the late 1980s.[47]

The building seems to have been constructed from an extension of an existing cottage, a second floor being added using sandstone, rather than whinstone, probably taken from the demolished Lambroughton End farm. Many alterations are visible with several closed off door ways and windows.

Mid Lambroughton Farm

Aitken's 1829 map gives the name Mid Lamberton and Ainslie's 1821 map only records the farm as Lambreighton. The farm is not marked on the Pont's (1604) or Armstrong's (1775) map. On 17 June 1821 John Calderwood and his spouse Jean Templeton in Mid Lambrighton (sic) had a lawful daughter born 16 May and baptized at Dreghorn parish church, named Jean. The farm was originally a single story height and was thatched, however following a fire it was given a second floor, the changes being clearly 'readable' in the stonework of the external walls. During renovations a fire charred beam was found, strong enough to have been retained. James Forrest was a noted botanist and an active member of the Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers around the 1930s. A 'James Forrest, Farmer' is acknowledged by Strawhorn[48] in his 'List of Helpers' for his account of the parish of Stewarton in 1951.

David Parker Forrest died on 11 January 1934 and is recorded on the impressive family memorial in Stewarton cemetery. The farm is marked on the 1858 OS with a milestone (Irvine 5¾ miles and Stewarton 1 mile) opposite its entrance, but now buried (see 'The Turnpike'). Close to the farm in a field near the 'cut' in the main road, is a large depression with a mound of earth, which is said locally to be the site of a meteorite strike. The 1897 OS of 25 inches (640 mm) to the mile and other more recent OS maps show no pond or mound, backing up this belief. Drains are shown on the 1789 Montgomerie Estate map anda small bog is indicate din the corner of the filed close to the toll road.[45] When new sheds were being constructed circa 1950 a stone axe head was found, now preserved in the Dick Institute.[42] A poem "The Bonnie Wood o' Lambroughton", written by Jim Forrest, is included in the 'Misc. Notes' section of this monograph.

West Lambroughton Farm

Aitken's 1829 map gives the name as both South and West Lamberton on different pages. The farm is not marked on the Pont's (1604) or Armstrong's (1775) map. The farm does not appear on Ainslie's 1821 map, however it does appears on Thomson's 1828 map, with Townhead of Lambroughton next to it, known as Lambroughtonhead in the Montgomerie Estate plans. Lambroughtonend Farm no longer exists, having been replaced by East lambroughton. A lane which ran down to a ford across the river Annick at Bankend. John Allan and his wife Margaret Hunter lived here in the 19th century. John died, aged 67 in 1885 and was buried in Dreghorn Parish churchyard. In 1788 - 91 a smithy existed near the farm on the other side of the road beside the lane running to the ford and stepping stones.[45]

Lambroughtonhead

As stated this farm is shown in the Montgomerie Estates plans by John Ainslie in 1789 as having existed on the other side of the toll road from West Lambroughton.

Lambroch Bridge, and the Garrier, Lochridge and Bracken Burns

| Etymology |

| The Garrier's name is thought to be derived, according to McNaught,[7] from the Gaelic 'ruigh or righ' meaning 'fast running water' The Scots word 'Gaw' is also the term given to a 'cut made by a plough' or a furrow or channel made to draw off water.[49] |

Lambroch bridge could be a bridge over the Annick, however it seems to be located by Pont where the Brackenburn has its confluence with the Garrier (Previously Gawreer) burn. Alton, the 'Old Ton' is near to this confluence and a bridge over the rivulet would be important for access as the flow of water would have been much more substantial than today, especially during floods and the bridge could double as a dam if required. The Garrier burn is now seasonal as its headwaters are the drained loch at Lochside near Buiston, pronounced 'Biston', (previously Buston). The word 'Gaw' is the term given to a 'cut made by a plough'. The Garrier is still pronounced locally as 'Gawreer' locally despite the cartographers best efforts to change it to Garrier.

The Buiston loch is famous as the site of the Dark Ages.[29][50] crannog (lake dwelling) discovered and excavated by Duncan McNaught.[7] Another possibility is that the bridge was over the Garrier burn near its confluence with the Lochridge (Lochrig) Burn between Cranshaw (now Hillhead) Farm and Wheatrig Farm. Some Ordnance Survey maps confuse the Brakenburn, which is near Kilmaurs, with the Garrier. A bridge would be a significant feature in the 17th. century, when a ford was the usual way in which rivers were crossed, as dangerous as this was. See the note on Maid Morville's Mound commemorating the drowning of a De Morville daughter at a ford on the river Irvine near Dreghorn.

Lambroughton Crossroads

The Lambroughton Crossroads were the site for festivities wehere the farm hands would meet for singing, dancing and trials of strength.[51] One 'ghost story' relates that when a well-liked and respected octogenarian farmer from West Lambroughton died in the 1990s, at around midnight on the night before the funeral the sound of dancing in hobnail boots could be heard coming from the crossroads with a Tawny Owl screeching its presence from a nearby telegraph pole for the first and only known time. The height above sea level is 74 metres at the centre of the crossroads.

Lambroch Mill

The existence of Lambroch Mill is shown up until 1775 (Armstrong, scale 1-inch (25 mm) to 1 Mile), however the positioning is not near the river and unless the Lochridge (formerly Lochrig) burn was used to fill a millpond then the site was probably on the River Annick (previously Annoch (1791-3), Annock or Annack Water) near where the farm of Laigh Castleton formerly Nether Castleton) is situated. At one time Laigh Castleton was part of the Robertland Estate and more recently the Lainshaw estate.

A well-made lane runs from Laigh Castleton down to the River Annick. The shape of the enclosure at the end of this road, the presence of piles of stones and what may have been a weir fairly conclusively show this to have been the site of the Lambroch Mill. The 1829 Robert Aitken's survey and the 1858 OS map indicates 'stepping stones' here (the old weir) and a ford a hundred metres or so upstream. A building is indicated, which may have been the grain store on the other side of the river, the ford would have provided easy access. A track from here, the grain store, to High Chapeltoun is shown on one of Aitken's maps. Ploughing in this field did not bring up asany stones, suggesting that this was a wooden building.[52]

Running from nearly opposite the present entrance to Townhead of Lambroughton is what appears to have been a lane in 1829, leading directly to Lambroch Mill, with hedgerow banks on either side. Grain could have been easily lowered down or flour hauled up from this lane's termination. This lane and the one to the mill site are clearly shown on the 1895 OS map, published in 1897. Laigh Castleton could also have been the miller's dwelling and farm, however it does not appear on a map by name until around 1828[53] and it is missing from Aitken's in 1829; the 1775 map has a building indicated, but it is named Mill, despite being set well back from the river. The name Mill could be interpreted as meaning that Laigh Castleton is linked with the mill though being the miller's dwelling. A 1779 Estate map of Lainshaw shows that lands to the East of the lane to the supposed mill belonged to Lambroughton.[54]

Thirlage was the feudal law by which the laird could force all those farmers living on his lands to bring their grain to his mill to be ground. Additionally they had to carry out repairs on the mill, maintain the lade and weir, as well as conveying new millstones to the site. The Thirlage Law was repealed in 1779[55] and after this many mills fell out of use as competition and unsubsidised running costs took their toll. This may explain why no sign of the mill is visible on Thomson's 1828 map, Aitken's 1829 map, or the 1858 OS map. Other mills, such as Dalgarven Mill near Kilwinning, survived almost to the present day through a mixture of luck, a reliable water supply and investment at the right time. Dalgarven Mill is now a museum. The last unrestored working mill in Ayrshire was Coldstream near Beith which last worked in 1979; the last traditional Ayrshire miller being Andrew Smith.

Floors Farm

On Aitken's 1829 map[40] Floors is written as Fleurs and in 1572 it was written as Fluris in a charter granted to John Cunninghame of Hill, Kilmaurs. The farm is recorded as Meikle Floors, meaning Large or Big Floors, on the 1911 OS map. One possibility is that the farm is named after William de Ferreres who obtained lands in Lambrachton and Grugere (now Grugar) from Hugo de Morville, upon his marriage to his daughter Margaret in the 14th century.[7] Allan de La Zuche married her sister Ela and was also given lands in Lambrachton and Grugere (now Grugar). It is not clear how the lands were apportioned other than the possible application of the name Ferreres to the farm now known as Floors, and thus a Ferreres to Fluris to Fleurs to Floors transition would provide a possible explanation. Floors does not however appear on either Pont's (1604–1608)[56] or Armstrong's (1775) map.

Alexander Orr and his wife Mary Galt lived at 'Mikle Floors', as recorded on their tombstone in Dreghorn parish churchyard. He died in March 1784 aged 73. The family appear to be related to the Orrs of Townhead of Lambroughton. William Mair and his spouse Jane Richmond farmed 'Floors' in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. William died aged 79 on 24 March 1908 and Jane aged 64 on 12 April 1900. A forgotten tragedy is that of the accidental drowning at Floors of their 18 month old son, William Wylie Mair, on 10 September 1864. They are all buried in the Kilmaurs-Glencairn church cemetery. The 1897 OS map shows two ponds at Floors, a fair sized one situated to the left of the slope leading up to the railway bridge on the farm side and the other, a smaller one, near the buildings on the Titwood side of the farm. In 1861 the Eglinton Papers show that new barns, etc. were built at Floors by the Earl of Eglinton.[45]

The Lady Constance coal mine was just across the railway line from the farm and was locally known as the 'Floors Mine'. Another Floors Farm is found at Eaglesham where Rudolf Hess crashed his Messerschmitt Bf 110 in 1941.

Alton, Wheatrig and Hillhead and Cranshaw Farms

Little Alton (Alton end in 1788 - 91[45]) had a sluice and a dam indicated in the 1860 OS, causing the Garrier Burn to form a pond in the area on the opposite side of the lane. The purpose of this arrangement is unknown, however a Crumshaw or Crunshaw Mill (Cranshaw) is mentioned in several early 17th-century documents and this may have been the site or possibly up at Lochend, which is also mentioned as existing at that time.[57] The name Cothouse is given to these two cottages in Aitken's 1829 map. A cothouse was a cottage tied to a farm labourer and latterly they were often used as homes for the old and infirm, usually widows. According to Aiton they had 'no internal partitions, no smoke-funnels or glass in the windows and had damp clay floors about 12 feet (3.7 m) square. Masons, wrights, smiths, shoe-makers and weavers sometimes lived in buildings of this general description.

Alton Farm (1912 & 1923), also Aulton (1820), Auldton, Auldtoun, Old Town (1807) and Oldtoun (1654 & 1775) has therefore been referred to as 'old' as far back as the early 17th-century and it may have been one of the first 'touns' in the area. The term alltan in Gaelic is however the diminutive of allt, therefore a little stream, which fits well.[58] Altonhead Farm lies nearby. As noted elsewhere, in 1675 Sir John Cunninghame Bart., conveyed to Robert Cunningham, druggist / apothecary, Edinburgh, the lands of 'Auldtoun, Langmuir, Langsyde and Lambrochtoune in whose family they seem to have remained until 1820, when George Cunninghame was the owner. The 1788 - 91 Eglinton Estate plans mark an Aulton Law just above the farm and below the small wood.[59]

A track ran from Wheatrig, (previously Whatrig,[60] Whiterig in 1775, Whiteriggs[59] in 1832 and Whyrigg in 1654) Farm to Hillhead Farm. A Cranshaw Farm is marked in 1832 and 1821, but not marked in 1775. A 'Cran' in Scots was a 'Crane or Heron' and the 'shaw' or small wood is still present. In the days when the loch was present cranes would have been a common sight and may even have nested in the wood, hence the name. Herons are still very common in the area. Cranshaw was a farm located near Little Alton on the northern side of the lane, clearly indicated in the Montgomerie Estate plans of 1788 - 91.[45]

James Templeton and his spouse Agnes Steele farmed 'Hillhead' in the late 19th century, with James dying on 14 March 1905 aged 84 and Agnes on 16 August 1902, aged 79. They were buried in the Kilmaurs-Glencairn church cemetery.

Robertson records that the widow of Mr. James Ross of Whiteriggs (Wheatrig), Christian Wallace daughter to the Laird of Auchans, married William Rankine of Shiel and thereafter became Lady Dreghorn. She had two children by this marriage, Robert and Catherine. John Cowan and his spouse Martha Martin farmed Wheatrig in the early 19th century, John dying aged 63 on 8 March 1836 and Martha on 16 October 1860. They are buried in the Kilmaurs-Glencairn church cemetery. The Eglinton estate improved the farm in 1862, building a turnip shed, milk house, etc.[45]

Between Hillhead Farm and Wheatrig Farm is a dwelling marked as Lochend on the 1860 OS, although it is not marked on earlier or later maps. It is mentioned, together with Crumshaw Mill in 1618.[57] It lies on the old track that connected the two farms and it is close to the confluence of the Garrier and Lochridge Burns, suggesting that a small loch or lochan could well have existed here. A wet meadow still exists at this point,[61] suggesting that the loch was drained during the period of agricultural improvements around 1775. A very large underground culvert was built to carry the large volumes of water away from this area, although its course is no longer known locally.[62] The Lochridge Burn, Garrier Burn and Brackenburn all merge before Alton Bridge. The old bridge here, with its proximity to the 'Old Toun', may have been the Lambroch Bridge marked on Pont's 1654 map.

Titwood Farm

Robbie Burns' uncle, Robert Burnes worked at Titwood Farm, later moved to Stewarton and was buried in the Laigh Kirk where a memorial was erected by public subscription organised by the Stewarton Literary Society. He is known to have helped guard the Stewarton Laigh Church graveyard against the activities of body snatchers.[63] Titwood (Tetwood in 1828) was also the last farm in the district to use a horse mill to drive farm machinery.[51]

The Turnpike and Milestones

Wheeled vehicles were unknown to farmers in the area until the end of the 17th. century and prior to this sledges were used to haul loads[48] as wheeled vehicles were useless. Roads were mere tracks and such bridges as there were could only take pedestrians, men on horseback or pack-animals. The first wheeled vehicles to be used in Ayrshire were carts offered gratis to labourers working on Riccarton Bridge in 1726. In 1763 it was till said that no roads existed between Glasgow and Kilmarnock or Kilmarnock and Ayr and the whole traffic was by twelve pack horses, the first of which had a bell around its neck.[64] A mill-wand was the rounded piece of wood acting as an axle with which several people would role a millstone form the quarry to the mill and to permit this the width of some early roads was set at a 'mill-wand breadth'.

General Roy's Military Survey map of Scotland (1745–55) marks the Lambroughton brae road as being part of the 'Post' road from Irvine to Glasgow, therefore giving it some importance as the mails were carried along it. This same road running up from Cunninghamhead was made into a turnpike by the 'Ayr Roads Act of 1767'[65] and the opportunity was taken to move the route away from Townhead of Lambroughton through which it used to run. The date of construction is unclear as the 1775 map doesn't show a new route. The nearest toll house was on the right as the road joins with the Stewarton to Kilmaurs road opposite the site of the old Lainshaw Mill and the Peacockbank toll.[60]

The name 'Turnpike' originated from the original 'gate' used being just a simple wooden bar attached at one end to a hinge on the supporting post. The hinge allowed it to 'open' or 'turn' This bar looked like the 'pike' used as a weapon in the army at that time and therefore we get 'turnpike'. The term was also used by the military for barriers set up on roads specifically to prevent the passage of horses. In addition to providing better surfaces and more direct routes, the turnpikes settled the confusion of the different lengths given to miles,[53] which varied from 4,854 to nearly 7,000 feet (2,100 m). Long miles, short miles, Scotch or Scot's miles (5,928 ft), Irish miles (6,720 ft), etc. all existed. 5,280 feet (1,610 m) seems to have been an average! Another important point is that when these new toll roads were constructed the Turnpike Trusts went to a great deal of trouble to improve the route of the new road and these changes could be quite considerable as the old roads tended to go from farm to farm, hardly the shortest route! The tolls on roads were abolished in 1878 to be replaced by a road 'assessment', which was taken over by the County Council in 1889.

Red sandstone milestones were positioned every mile. Only one survives in the hedge opposite the entrance to the upper Law Mount field, indicating Stewarton 1-mile (1.6 km) and Irvine 6¾ miles, another was positioned opposite the entrance to Mid Lambroughton farm and as with the others the only remaining clue is a 'kink' in the hedgerow as seen near Langlands Farm. The milestones were buried during the Second World War so as not to provide assistance to invading troops, German spies, etc.[66] This seems to have happened all over Scotland, however Fife was more fortunate than Ayrshire, for the stones were taken into storage and put back in place after the war had finished.[67]

The short section of woodland on the right beyond Castleton heading towards Stewarton is known as Peter's Brae or Peter's Planting on the 1779 estate map and the 1858 OS. The identity of Peter is unknown. Just beyond this point is an entrance gate with sandstone gateposts and a short wall either side, which was the end of the original driveway down from Lochridge House. Later it branched off next to Peacockbank (previously Pearcebank) Farm from what is now the main road, but which didn't exist. One branch went to Stewarton and the other to the Irvine road. The OS map of 1911 clearly shows the routes taken and the 1779 map shows only the old entrance onto the Irvine road.

Thomas Oliver. "roadmaker in Stewarton" estimated in 1769 that the Kilmarnock to Irvine Toll Road would cost seven shilling per fall from Annick Bridge to Gareer Burn, but ten shillings per fall from Gareer Burn to Corsehouse bridge (Crosshouse) because of the lack of suitable materials locally.[68]

Limekilns

Limekilns are a common feature of farms in the area and limestone was quarried locally. Limekilns seem to have come into regular use about the 18th century and were located at Wheatrig, Haysmuir, Bonshaw, High Chapeltoun, Sandylands (now Bank End) and Alton. Large limestone blocks were used for building but the smaller pieces were burnt, using coal dug in the parish[69] to produce lime which was a useful commodity in various ways: it could be spread on the fields to reduce acidity, for lime-mortar in buildings or for lime-washing on farm buildings. It was regarded as cleansing agent.

Natural history

Hares are a common site on the Kilmaurs road near the Townhead of Lambroughton old entrance, but rabbits are a rarity hereabouts. Foxes can be seen and heard in the woods by the Annick and migrating geese use the fields as a migration stop. Lapwings are an annual visitor as are the swallows and housemartins which nest in the buildings of East Lambroughton farm. Other species present are the pipistrelle bats, moles, hedgehogs, toads, kestrels, treecreepers, ravens, wagtails, sparrows, blue-tits, great-tits, pleasants, snipe, wrens, buzzards, chaffinches, blackbirds, greenfinches, rooks, etc. The rare Hummingbird Hawkmoth was seen near the Lambroughton Crossroads in 1985 and Duncan McNaught[7] also recorded this species in 1912.

The Stewarton Flower

The Stewarton Flower, named for its local abundance by the Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers, is otherwise known as Pink Purslane (Claytonia sibirica) is found in damp areas. This plant was introduced from North America, quite possibly at the Lainshaw Estate for in the Anderson Plantation it is almost the dominant undergrowth species. The white flowered variety was introduced here and the normal pink variety spread from elsewhere. As far away as Dalgarven Mill the white flowered variety still dominates. The plant is very adept at reproducing by asexual plantlets and this maintains the white gene pool around Stewarton. The pink variety has not been able to predominate here, unlike almost everywhere else in the lowlands of Scotland, England and Wales.

Barony of Roberton

Robertson[15] mentions this barony, once part of the Barony of Kilmaurs, which ran from Kilmaurs south to the River Irvine. It had no manor house and belonged to the Eglinton family latterly. Hugh Montgomerie, Ist Earl of Eglinton, had a charter on 3 February 1499 from James V of the £40 lands of old extent of Roberton in Cunninghame.[70] These lands were part of the Lands and Barony of Ardrossan at one time; the following properties were part of the barony: parts of Kilmaurs, Knockentiber, Craig, Gatehead, Woodhills, Greenhill, Altonhill, Plann, Hayside, Thorntoun, Rash-hill Park, Milton, Windyedge, Fardelhill, Muirfields, Corsehouse.[45] Smith states that Roberton castle belonged to the Cunninghames, but had been completely rooted out by the 1890s.[71]

Thorntoun Estate

Thorntoun house and estate was part of the ancient Barony of Robertoun and is first recorded as belonging to a branch of the Montgomeries, descended from Murthhaw Montgomery, who is mentioned in the Ragman's Roll of 1296. A Johne of Montgomery of Thornetoun is mentioned in a legal document of 1482.[28] By the beginning of the 17th century Thorntoun had passed into the ownership of another ancient and renowned Ayrshire family, the Mures, a branch of the Mures of Rowallan Castle near Kilmaurs. Some confusion exists in the surviving records, for either an Archibald or a James Mure , Burgess of Glasgow, married Margaret, daughter of Robert Ross of Thorntoun on 27 June 1607. Nothing is known of how and when this Ross family came to possess Thorntoun. A Hew Muir was one of their sons, and another, James Muir of Thorntoun, married a Janet Naper, who died in 1626. Robert Muir, son of James & Janet, is mentioned in a document of 1634.

An Archibald Muir of Thorntoun was knighted by William III in 1699 and his daughter, Margaret, married John Cuninghame of Caddel, in Ardrossan. Their son, Lieut-Col. John Cuninghame of Caddel & Thorntoun was born in 1756 and died in 1836. John's spouse was Sarah Peebles, who was born in 1783 and died in 1854. They had six children, Andrew, Anna, Archibald, Christiana, Margaret and Sarah. They all died relatively young, except for Sarah who survived to inherit Thorntoun. Her spouse was George Bourchier Wrey. They had a son, George Edward Bourchier Wrey who had succeeded to the property by 1912.[7] The Lieut-Col and his family are buried or commemorated at the family burial plot in the cemetery of Kilmaurs-Glencairn kirk.

Other items of interest in the locality

The Law Mount or Moot Hill

The Law Mount (OS maps), Castleton Law mount,[54] Moat Hill[40] or Moot Hill[52] overlooking Lainshaw House and above Castleton (previously Over or High Castleton) is an artificial mound which was thought to have a bailey and therefore be a castle motte, hence the name of the farms. Linge[72] is of the opinion that the supposed bailey, clearly visible from the road under the appropriate light conditions, is a natural geographic feature. The mound is 19 m in diameter and 3.5 m in height. At the top its diameter is 12 m and seen by satellite imagery it is clearly too small to have been a motte, however it may originally have only been an observation post.[73] It is locally known as 'Pinkie Hill' or the 'Jerry's helmet'.[74]

Carmel Bank House was formerly known as 'Mot' or 'Mote' House and was the site of a Motte Hill.[7]

Another possibility that suggests the secondary use of the mound and fits with its more recent local names, is that it was the site of the Justice Hill where proclamations of the Lainshaw Castle or possibly the Lambroughton Baronial Court's judgements and sentence was carried out here. For serious crimes the men were hung here and women were drowned in the Annick Water below the mound. This situation, known as the feudal Barony right of 'pit and gallows' existed at many other sites, such as at Kilmarnock, Aiket, Ardrossan, Dalry, Largs, Carnell, Giffen and Mugdock where the castle, mound and lochan have this scenario attached to their history. The Boyds, Lords of Kilmarnock, had their gallows at Gallows-Knowe which stood in Wellington street.[75] Often the mounds were wooded and a Dule Tree may have been used as the gallows. Brehons or Judges administered justice from these 'Court Hills', especially in the highlands. Aiket castle had a court hill mound nearby, as did Riccarton which is now the site of a church and the village of Tinwald exists near Dumfries its name is derived from the same root as that of the famous Tynwald parliament site in the Isle of Man.

High Castleton had been a part of the Robertland Estate and was farmed by William Smith and his spouse Jessie Gibson in the late 18th century. William died aged 83 on 14 December 1913, whilst Jessie died aged 64 on 7 April 1895. They were both buried at the Laigh Kirk, Stewarton. The fields between the Law Mount and Laigh Castleton were known by the quaint names of East and West Tinkerdyke Parks.[54]

Gibbie the Fox-Killer

Hunter or Tod Gibbie was a character in Sir Walter Scott's Guy Mannering, based on Gabriel Young who lived in Kilmaurs. Gabriel had a pack of twelve slow-hounds to give tongue, six greyhounds to catch by speed and eight terriers to deliver the coup de grâce. The hunts were always on foot, often of short duration and accompanied by all and sundry. He was paid, just like the mole-catcher, to rid the farms of foxes without any notions of sport. Gibbie was the last of his kind.[7]

Christian Shaw and the witches

At the age of 11 this young girl, daughter of the Laird of Bargarran, in the parish of Erskine, took a violent dislike to one Catherine Campbell, a domestic servant. Christian decided to achieve the death of Catherine by feigning possession by evil spirits, so she threw fits with violent contortions of her body and ejected egg-shells, fur balls, chicken bones, etc. forth from her mouth. So convincing was she, that she achieved a great deal of attention, and this encouraged her in the end to accuse twenty-four men and women, old and young, of taking an oath to follow Satan. Six were hung and then burned at Paisley and one committed suicide in gaol in 1697. Strangely several of her victims willingly confessed their pact with the Devil. This was one of the most cunning and diabolical episodes in the annals of witchcraft, however Christian was never held to account and went on to marry Mr. Millar, the minister of Kilmaurs from 1718 - 21[76][77] and after his death actually set the foundations for the thread manufacturing trade of Paisley.[7][78]

The Kilmaurs Burgh of Barony

In 1577 (Strawhorn gives 1527), King James V erected Kilmaurs as a Burgh of Barony, under a charter from Cuthbert, 3rd. Earl of Glencairn. 240 acres (0.97 km2) of rich land, in lots of 6 acres (24,000 m2) each, was apportioned to 40 persons in order to 'induce mechanics to reside in Kilmaurs', such as shoemakers, cutlers, skinners, carpenters, waukers and wolsters. At one time 30 cutlers and a good many tinkers resided in Kilmaurs and gave the town a reputation for craftmanship which lingers on to this day (2006).[29][79] James, the fourteenth Earl of Glencairn broke the centuries old connection of the Cunnighame family with the area by selling the estate of Kilmaurs in 1786 to the Marchioness of Titchfield.[15]

The Lifters and Non-Lifters

The Secessionists were those who had split in the 18th century from the established Presbyterian church. David Smyton or Smeaton had been 'called' to Kilmaurs, however he developed the belief that in the dispensation of the Sacrament, it was essential that the bread must be first lifted before being blessed. Such a small point was not taken very seriously by Smeaton and he fought hard for in his view Divine Authority would accept no latitude in this matter. The Weston Tavern was formerly Smyton's manse, built in 1740, however it was disposed of in 1789 upon his death. The 'Non-lifter' congregation built a meeting house and manse at Holland Green on the Fenwick Road. Tradition has it that Smyton forgot to 'lift the bread' at his first service following his victory in maintaining the possession of the Secession church in Kilmaurs.[80] Robert Burns must have heard him preach and commented in a letter to Margaret Chalmers in 1787 that "The whining cant of love, except in real passion, and by a masterly hand, is to me as insufferable as the preaching cant of Old Smeaton, Whig minister at Kilmaurs.".[7][15]

Tour, Kirklands and Pathfoot

The Abbot of Kelso granted part of these 'Lands of Touer' to David Cuninghame of Robertland in 1532. The property stayed in the Robertland family and their descendants until 1841, when Robert Parker Adam purchased the lands and rebuilt the Mansion House in the old English style.[9] Tour (Tower in 1820) has an ice house. A copper alloy flanged axehead was found by a metal-detectorist in a ploughed field near Tour House in 1991. It is now in the Glasgow Kelvinside Museum. William Cathcart had the property in 1820 with a rental value of £126 4s 10d Robertson.[15]

At NS44SW 36 414 406 an old inhabitant in 1912, backed by other reliable informants, stated that in his grandfather's time there were a few thatched cottages, forming a small hamlet called Pathfoot, near the vicarage tower; the site now forms part of the Tour plantation, which extends W to the railway viaducts over the Carmel Water. All traces of Pathfoot have long ago disappeared.[7]

The Darien affair

The Darien Company was an attempt by the Scots to set up a trading colony in America in the late 1690s, however the opposition from England and elsewhere was so great that the attempt failed with huge losses and great financial implications for the country and for individuals. Half of the whole circulating capital of Scotland was subscribed and mostly lost. In Cunninghame some examples of losses are Major James Cunninghame of Aiket (£200), Sir William Cunninghame of Cunninghamhead (£1000), Sir Archibald Mure of Thorntoun (£1000), William Watson of Tour (£150) and James Thomson of Hill in Kilmaurs (£100).

Knockenlaw Mound and the De Soulis family

This mound, called Knockinglaw on the 1896 OS, still exists in very poor condition, near Little Onthank. It was a tumulus in which urns had been found.[52] It had a powder magazine built into it at one stage and was eventually effectively removed altogether. It is involved in one of the versions of the stories of the killing of Lord Soulis. He is said to have been killed here in 1444 after leading a band of English mercenaries into the Kilmarnock area and then subsequently suffering a rout at the hands of the Boyd's of Dean Castle. Dean Castle at one time belonged to the De Soulis family. A memorial stone, dating from at least 1609, to Lord Soulis is to be found set into a wall at the High Church, by the railway viaduct.[75] A brass placque with details of the De Soulis coat of arms used to be set into the road near this spot. The Soulis Cross was in Soulis Street, but is now housed in the Dick Institute. A notorious Lord Soulis is linked with the evil Redcaps at Hermitage Castle in the Borders. He could only be bound by a three-stranded rope of sand, but they got over the problem of hanging him by binding him in a lead sheet and boiling himn to death for the murder of the Laird of Branxholm.[81] Robertson[15] points out that the coat of arms of the De Soulis & De Morville families is identical and they may therefore have been related. The De Soulis family lost their lands due to their involvement in 'The Soulis Plot' to depose Robert the Bruce. The family were unsuccessful claimants to the throne of Scotland.

A final role of the mound was in the holding of a 'court' at Knockenlaw by the Earl of Glencairn when he was attempting to claim the Lordship of Kilmarnock from the Boyd's. In the event the supporters of the Boyd's turned up in force and the Earl had to abandon his attempt. The Roman Well, said to be of great antiquity was located nearby. These sites are now hidden beneath housing estates.

Micro history, traditions and archaeology

| Etymology |

| Carmel, the oldest form of which is Caremuall, is thought to be derived, according to McNaught,[7] from the Gaelic 'Car' meaning a 'fort', and 'Meall'. meaning a hill. Therefore, 'The fort on the hill'. |

In 1780 Kilmarnock Council paid Robert Fraser 2s. 6d. for dressing a Maypole, one of the last recorded examples of the rural festival of the first of May in Scotland, having been put down by Act of Parliament immediately after the Reformation.[9]

McNaught[82] records that John Armour was a resident clockmaker in 1726, with Kilmaurs clocks regarded as having brass dials of the highest standard. He had one arm shorter than the other and was called 'Clockie' for this reason.[83]

Both Beattie[16] and the Kilmarnock Glenfield Ramblers refer to the iron bridge over the Carmel Water near Kilmaurs-Glencairn church as being the oldest iron bridge in Scotland. It was erected following a 1d subscription from each of the house-houlds of Kilmaurs. The council demolished it without consultation in around 2000 and replaced it with a wooden bridge.

John Gemmell is buried in Kilmaurs-Glencairn chuchyard. He was surgeon to the Royal American Reformers, one of the loyal militias who fought against the American 'rebels' in the American War of independence.

Templehouse and its associated fortalice are mentioned by Dobie[28] and were located in Stewarton on the lands of Meikle-Corsehill Farm. The name Templehouses was still current in the 1860s on the OS map for the tenements along from the Mill House Inn. The fortalice is not marked, however an area on the opposite side of the road from Templehouses was known as 'The Castle' within living memory.[84] Robertson in 1820 gives the proprietor as William Deans Esq. and the rental value as £13.

Morton Park overlooked by Kilmaurs Place in was gifted by the Morton family of Lochgreen in 1921 and the official opening was 9 September 1922.[85] A terrapin was found living in the Carmel burn in 2006. Kingfishers were seen there in 2004, 2005 and 2006. Mink were seen in 1995 and 2000. Dippers and Grey Wagtails are regularly sighted.[85]

The poet William C. Lamberton of Kilmaurs was also a shoemaker and the Kilmarnock town chaplain. He published a volume of verses in 1878 under the nom de plume of 'An Ayrshire Volunteer'.

The Monk's or Mack's Well water runs into the Carmel beneath Kilmaurs Place. It is said that many years ago the local lord tried to prevent the local people from using the well. It dried up until the lord changed his mind, but has run continuously ever since.

In 1820 Kilmaurs Parish had only four freeholders qualified to vote and Dreghorn had only five, these being the proprietors of Cunninghamhead, Annock Lodge, Langlands (2) and Warwickhill. On Saturday, 3 March 1827 a remarkable snow-storm hit Ayrshire. The snow lay up to twenty feet deep in places and it snowed for twenty-four hours. A strong wind got up and drifts covered even the tops of the hedges so the roads were all but hidden.[75]

A Mrs Lambroughton lived at Fulshaw Farm in the 1950s, a rare example of the name being used in this form. The name is still (2006) linked to Fulshaw Farm Cottage.

In Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English Church and People written in AD 731 is recorded the case of a Cunningham of Northumbria who died after a gradually worsening illness. All his grieving family were gathered around his corpse when he suddenly sat up. Everyone ran away, apart from his wife to whom he told the story of his adventure. He had been guided in death by a man in a shining robe to a broad, deep, dark valley of infinite length and from here he crossed a high wall beyond which was a broad and pleasant meadow. His guide told him that he had to return to live amongst men again and despite his reluctance to go he found himself back in his body again, alive.[86]

Standalane—a number of properties in this area have this name, however no obvious pattern exists, other than its humorous use in connection with lonely or solitary places[58] or a dwelling just outside a village or town.

Aiton[79] in 1811 mentions "a curious notion that has long prevailed in the County of Ayr, and elsewhere, that the wool of sheep was pernicious to the growth of thorns."

Feuds were a feature of life in old Ayrshire and in 1547 Sir Neil Montgomerie of Lainshaw was killed by Lord Boyd of Kilmarnock in a skirmish which took place in the streets of Irvine (Robertson 1908).

Near Langlands Farm in the hedgerow of the main road is a rare example of a Wild Pear tree. The blossom is outstanding in the month of May, but in the absence of another tree nearby it doesn't set fruit. The nearest grows near Chapeltoun Mains.

The old sandstone parapet of the bridge overlooking the site of Cunninghamhead railway station has many carvings on it, probably made over the years by local children and pupils from the primary school as they waited and watched the old steam and diesel trains going by on this long closed line. Extensive cattle sidings and docks can still be made out here (2006). Ayrshire or Cunninghame Cattle were sent from here to all parts of the United Kingdom and Empire beyond. Ayrshire Cattle were sent from nearby Wheatrig Farm to restock the Falkland Islands after the war with Argentina.

A number of small whinstone quarries were also present in the area, such as at Townhead of Lambroughton on the 1858 OS. The area is later marked as a fox covert and the old road down from Floors ran beside it.

An unusual feature of Kilmaurs Mill was a carved stone showing a millstone drive spider or rind (often used on Miller's tombstones as a symbol of the milling trade) on which the upper grindstone rested, a ring of rope, a bill for dressing millstones, and a grain shovel.

A ball of fine-grained sandstone, 2½ ins in diameter, with the surface ornamented by six equal, circular and slightly projecting discs, found at Jock's Thorn farm (NS 417 410).[86][87] 387 are known from Scotland, but only two from Ayrshire. They are from the neolithic or Bronze Age and their function is not known, however they may be symbols of power, equivalent to the orb in the British Coronation ceremony.

In 1911 McNaught[7] records the last sighting of an otter. This took place at the Brackenburn Bridge on 9 September in full moonlight. They have probably made a comeback in the last few years (2000–2006).

Next to the Kilmaurs-Glencairn church is a patch of woodland which was once an orchard. The Tour streamlet joins the Carmel nearby and before the confluence can be found an old well, arched over, known as the Lady's well, with never-failing, excellent and refreshingly cool water. A small wooden bridge used to run across to it from the church glebe side.[7]

Lord John Boyd Orr, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize was born in Holland House on the Fenwick Road in Kilmaurs. He may have been related to the Orr's of Townhead of Lambroughton.

The dovecot at Tour below Kilmaurs-Glencairn Church is dated 1636 on its door lintel (not 1630 as stated by McNaught[7]). It is rectangular on plan, with a centre ridge roof and crow-stepped gables. Only the foundations of the tower still exist, the remains having been taken down in the late 20th century. Kilmaurs was spelt Kylmawse in Circa 1564 (1980). The fields below the kirk, running down to the footbridge over the Carmel are named in the 1860 OS. 'Broomy knowe', presumably named after Broom and the knowe on which the old orchard was situated, lies to the left of the Tour rivulet. Bounded by the hedge on the right and the rivulet on the left is the 'Dovecot Fauld'. The Scots term 'fauld' means a meadow which is manured by keeping animals on it; pigeon droppings from the nearby dovecot seem to have been used, at least in part, judging from its name. Finally, the field on the other side of the hedge, running towards the Carmel is called 'Girnal', meaning a granary in Scots, suggesting that such a building once stood hereabouts. These fields seem to have formed the glebe of the kirk.

Kilmaurs Council House had the top twelve feet of the steeple thrown down by a lightning strike in 1874. The front steps were smashed, but no one came to harm. The "juggs", which dangle from an iron chain, were last used officially in 1812 to hold a young woman who had been found guilty of theft. She was later drummed out of the parish by a mob.[88]

The Stewarton cricket ground was located between Wardhead House and Lochridge House. A golf course also existed here for a few years after WW2.[63]

The Royal Mail re-organised its postal districts in the 1930s and at that point many hamlets and localities ceased to exist officially, such as Templehouse, Darlington, Goosehill and other areas in Stewarton.[29]

Kilmaurs was famous for producing cutlery and swords, the local expression As Gleg as a Kilmaurs Whittle, with the addition that it cuts an inch before the tip; meaning "the sharpest of the sharpest". A restaurant by the name of the Gleg Whittle existed here until 2006.

The Parish council chambers in Kilmaurs, the 'juggs' or 'jougs', has a fine example of a stepped Mercat Cross in an enclosure behind it, the cross is surmounted by a large sandstone ball and dated 1830.

The Bonnie Wood o' Lambroughton'

|

Views in Kilmaurs

-

The Mercat cross at the 'jougs'

-

The '1830' date on the Mercat cross

-

The 'jougs'

-

The old Parish Council building

-

Pollarded trees on a driveway in Fenwick Road

-

Glencairn Kirk in Fenwick Road, built in 1864

-

The birthplace of Lord Boyd Orr - Holland Green, Fenwick Road

-

The Knoll or Knowe on the Cunninghamhead road, locally known as Bowie's Munt

-

Gravestone of John Gemmell. He was a surgeon to the American Royal Reformers, fighting with the regular army in the American War of Independence.

-

A view of the old 1830s firestation in the 'Jougs'. The doors to the right of the stone pillars.

-

A view of the old 1830s fire station in the 'Jougs'

-

The Carmel Water in Kilmaurs at the inflow of the Mack Well (see the rings in the water) near the Auld Brig

See also

- Chapeltoun

- Cunninghamhead

- Corsehill

- William de Lamberton

- Dean Castle

- 's_Guide_to_Local_History_Terminology A Researcher's Guide to Local History terminology

- Lady's Well

- Cunninghamhead, Perceton and Annick Lodge

- Thorntoun Estate

- Lambroughton Loch

References

- ↑ Scottish Genealogical Society

- ↑ Urquhart, Page 89

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. Pub. J. Murray. London. Vol. II. P. 144.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 MacIntosh, John (1894). Ayrshire Nights Entertainments: A Descriptive Guide to the History, Traditions, Antiquities, etc. of the County of Ayr. Pub. Kilmarnock. P. 195.

- ↑ Taylor, G. and Skinner, A. (1776) 'Survey and maps of the roads of North Britain or Scotland'

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Best, Nicholas (1999). The Kings and Queens of Scotland. Pub. London. ISBN 0-297-82489-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 7.9 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 7.20 7.21 7.22 7.23 7.24

- McNaught, Duncan (1912). Kilmaurs Parish and Burgh. Pub. A.Gardner.

- ↑ Earls of Eglinton. Ref. GD3. National Archives of Scotland.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Paterson, James (1863-66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. V. - III - Cunninghame. J. Stillie. Edinburgh.

- ↑ Cunningham, Page 59

- ↑ Service, Page 105

- ↑ Young, Alex F.(2001). Old Kilmaurs and Fenwick. ISBN 1-84033-150-X.

- ↑ Groome, Francis H. (1903). Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland. Pub. Caxton. London. P. 938.

- ↑ Dillon, William J. (1950). The Origins of Feudal Ayrshire. Ayr Arch & Nat Hist Soc. Collections. Vol.3. P. 73

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5

- Robertson, George (1820). Topographical Description of Ayrshire; more Particularly of Cunninghame: together with a Genealogical account of the Principal families in that Bailiwick. Cunninghame Press. Irvine.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Beattie, Robert (1990). Kilmaurs Past and Present. Kilmaurs Historical Society.

- ↑ Salter, Mike (2002). The Castles and Tower Houses of Cumbria. Folly Publications. ISBN 1-871731-36-4.

- ↑ Kennedy, Jim (2010). The Abbey of Kilwinning. Chapter 8

- ↑ Commisariot of Glasgow Wills from the Commissariot of Glasgow 1547

- ↑ Oram, Richard D. (1999) Devorgilla, The Balliols and Buittle. Transactions of the Dumfrieshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society. LXXIII. P. 165 - 181.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. Pub. J. Murray. London. Vol. II. P. 127 -128.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. Pub. J. Murray. London. Vol. II. P. 148.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. Pub. J. Murray. London. Vol. II. P. 254.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. Pub. J. Murray. London. Vol. I.

- ↑ Dalrymple, Sir David (1776). Annals of Scotland. Pub. J. Murray. London. Vol. II. P. 327.

- ↑ Dick Cunyngham's papers. Scottish National Archives. Ref. GD1/1123/38.

- ↑

- Metcalfe, William M. (1905). A History of the County of Renfrew from the Earliest Times. Paisley : Alexander Gardner. p. 121

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Dobie, James D. (ed Dobie, J.S.) (1876). Cunninghame, Topographized by Timothy Pont 1604–1608, with continuations and illustrative notices. Pub. John Tweed, Glasgow.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 Strawhorn, John (1975). Ayrshire. The Story of a County. Ayrshire Arch & Nat Hist Soc p. 67.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Paterson, James (1863). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Pub. James Stillie. Edinburgh. Vol.1.-Kyle. P. 649.

- ↑ Millar, A. H. (1885). The Castles & Mansions of Ayrshire. Reprinted The Grimsay Press. ISBN 1-84530-019-X. P. 44

- ↑ Paterson, James (1863). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. Pub. James Stillie. Edinburgh. Vol.1.-Kyle. P. 65 - 652.

- ↑ Plan of the Barony of Kilmaurs. Scottish National Archives. Ref. RHP35796/1-26.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Douglas, Robert (1764). The Peerage of Scotland. Pub. R. Fleming. P. 289.

- ↑ Farewell to Feudalism Retrieved : 2010-10-13

- ↑ Mack, James Logan (1926). The Border Line. Pub. Oliver & Boyd. Pps. 317–322.

- ↑ Armstrong and Son. Engraved by S.Pyle (1775). A New Map of Ayr Shire comprehending Kyle, Cunningham and Carrick.

- ↑ Arrowsnith, Aaron (1807). A Map of Scotland Constructed from original Materials.

- ↑ Ainslie, John (1821). A Map of the Southern Part of Scotland.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Aitken, John (1829). Survey of the Parishes of Cunningham. Pub. Beith.

- ↑ Lairds of Lambroughton. Ref. GD1/1123/37. National Archives of Scotland.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Forrest, Jean (2006). Oral Communications to Roger S.Ll. Griffith

- ↑ Reid (1910). Family History. Private Publication.

- ↑ Chapeltoun Mains Archive (2007) - legal documents of the Lands of Chapelton from 1709 onwards.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 45.5 45.6 45.7 45.8 National Archives of Scotland. RHP35796 / 1 - 5.

- ↑ Roys Map

- ↑ Roberts, Richard (2006). Oral communication with Griffith, R.S.Ll.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Strawhorn, John and Boyd, William (1951). The Third Statistical Account of Scotland. Ayrshire. Pub. P.879.

- ↑ Warrack, Alexander (1982)."Chambers Scots Dictionary". Chambers. ISBN 0-550-11801-2.

- ↑ Crone, Anne (2000) The History of a Scottish lowland Crannog: Excavations at Buiston, Ayrshire 1989 - 90. Pub. Scottish Trust for Archaeological Research. ISBN. 0-9519344-6-5.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Hastings, John (1995). Oral communication to R.S.Ll. Griffith

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Smith, David (2006). Oral Communication with Griffith, Roger S.Ll.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Thomson, John (1828). A Map of the Northern Part of Ayrshire.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 National Archives of Scotland. RHP/1199.

- ↑ Ferguson, Robert (2005). The Life and Times of the Dalgarven Mills. ISBN 0-9550935-0-3. P. 4.

- ↑ Pont, Timothy (1604). Cuninghamia. Pub. Blaeu in 1654.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Earls of Glencairn papers. (1618) Ref. GD39. Scottish National Archives.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Johnston, James B. (1903), Place-Names of Scotland. Pub. David Douglas, Edinburgh. P. 10.